Brand Luther: How an Unheralded Monk Turned His Small Town Into a Center of Publishing, Made Himself the Most Famous Man in Europe--And Started the Protestant Reformation (17 page)

Authors: Andrew Pettegree

Tags: #Religion, #Christianity, #History, #Modern, #General, #Europe, #Western

When Luther first appeared before Cardinal Cajetan he was not aware of the recent turn of events in Rome: that his views had formally been condemned as heresy, requiring of him now an unambiguous act of contrition, otherwise sentence of excommunication would be pronounced. These new constraints had been conveyed to Cajetan, who wisely had chosen not to share this bleak turn of events with Luther’s protector, Frederick. It meant, however, that Luther brought to his interview with Cajetan utterly unrealistic expectations of what could be achieved by their discussion.

This was a tragedy for the church, which thus passed up the last slim hope of reconciliation. But it was doubly a tragedy for Cajetan, who of all Luther’s opponents was best equipped to engage with this curious man, who now, on their first meeting, prostrated himself at the cardinal’s feet, as convention demanded. Discussion began in a cordial enough tone, but soon the hopeless impasse was revealed. Luther asked the cardinal to elucidate the reasons behind the church’s rejection of his propositions; Cajetan insisted on obedience and submission.

This was a shattering encounter for Luther that stripped away much of

his remaining faith in the church hierarchy. Their last meeting having ended with angry words on the cardinal’s part, Luther lingered for some days in increasing anxiety lest his safe-conduct be revoked. Finally, on the evening of October 20, Luther slipped away, taking leave of the cardinal by letter. His formal appeal against Cajetan’s proceedings was posted on the door of Augsburg Cathedral two days later by a friend. Luther arrived back in Wittenberg on October 31, the first anniversary of the posting of the theses. How utterly his life had changed in these twelve tumultuous months.

For the moment Luther was safe, but for how long? He was pursued back to Wittenberg by a letter from Cajetan, requesting the elector to hand Luther over to be conducted to Rome. It was only in December that Luther became aware that Frederick would refuse. He occupied the time by writing a short account of the meeting in Augsburg; on November 18 he also formally appealed the pope’s anticipated judgment to a meeting of the general council. The general council, an assembly of cardinals and other leading churchmen that had met intermittently over the preceding centuries, had played the decisive role in ending periods of schism during the medieval era, and was still evoked by reformers as an alternative source of authority to an increasingly imperial papacy. It would, of course, ultimately be such an assembly, the Council of Trent, that would take the crucial steps toward a reformed and revitalized Catholicism. But the general council could only be summoned by the pope, and it was wholly implausible to imagine that such a gathering would be convened to hear Luther’s case. Initially Luther’s appeal was most likely conceived as a legal maneuver to strengthen the elector’s position in defying a clear instruction from the pope’s representative. But in the years to come this assertion of the primacy of the authority of the general council, a relic of the conciliarist dispute of past centuries, became an increasingly important aspect of Luther’s gradual rejection of papal power. In due course the hopes of a reforming general council would be a fixed point in the agenda of reconciliation fitfully pursued by Catholics and evangelicals after the decisive Protestant breach. Both the

Acta Augustana

and the text of Luther’s appeal (

Appellatio

) were swiftly

published in Wittenberg, then in Leipzig and Basel; in the case of the

Appellatio,

Luther claimed, prematurely and against his will.

17

While he normally denounced Rhau-Grunenberg for his slow work, in this case Luther claimed he had jumped the gun; he had given the text to the printer but had intended it to be distributed only after news arrived of his formal excommunication.

18

This has the whiff of scapegoating, an explanation cooked up by Luther when friends taxed him that the appeal was premature and possibly counterproductive.

For affairs in Rome had reached a delicate stage. Rather than proceed to immediate judgment—pointless while Luther was safely tucked away in Wittenberg—Rome embarked on a new round of diplomacy. This new mission was entrusted to Karl von Miltitz, a vain and not especially subtle papal councillor, whose attempt to broker a solution in his native Saxony occupied much of the winter and the early months of 1519. Frederick and Luther were happy to engage with von Miltitz, not least because his arrival in Germany had convinced the envoy of the genuine sympathy for Luther’s cause. Luther was prepared to cooperate in the draft of a letter of apology to the pope, which mostly, however, skirted around the theological questions at issue. At this point political perspective altered dramatically, and decisively in Luther’s favor. On January 12, 1519, the Emperor Maximilian died. In the election to choose his successor, his grandson Charles of Spain would be the strong favorite. But nothing was certain, and Frederick, as dean of the electoral college, would play a vital role.

Suddenly the matter of Frederick’s protégé appeared in a different light, particularly as Pope Leo had his own reasons for wishing another candidate to succeed to the imperial throne. On March 29, 1519, the pope wrote directly to Luther, addressing him as “beloved son” and rejoicing in his willingness to recant (in this Leo was misinformed). No longer was Luther the “insolent monk” or “son of perdition” whose case was already closed.

The maneuvers surrounding the imperial election won Luther a six-month respite, an interval he would occupy with further writing and

teaching. It was in this period particularly that Luther developed his pastoral role with a series of short treatises on subjects of immediate concern to lay Christians: on the Lord’s Prayer, on the body of Christ. All were swiftly reprinted in numerous editions. Luther also occupied himself with revising his lecture series on Galatians from the academic year 1516–17 as an academic commentary. This was handed over to the Leipzig printer Melchior Lotter in May, though it did not appear until September.

19

During this comparatively tranquil interlude it was left to Luther’s German opponents to pursue the theological quarrel. Foremost among them was Johann Eck. Still smarting from Luther’s reply to his “Obelisks,” Eck had little doubt that the public exposure of Luther’s teaching would reveal the full extent of the emerging Wittenberg heresies. Luther’s loyal but impetuous Wittenberg colleague, Andreas von Karlstadt, had provided the opening with his 406 theses against the “Obelisks.” In his published response Eck challenged Karlstadt to a public disputation, with Karlstadt to choose the venue. Originally set for April 1519, in due course the disputation was fixed for Leipzig in June.

This put Luther in something of a bind.

20

He was aware, of course, that he was the real target. He was also uncertain how effectively Karlstadt would plead his cause. When Eck published a set of twelve theses as the basis of the debate, Luther published countertheses of his own; he also proposed himself as the appropriate disputant. This change in arrangements could not, however, be made without the agreement of the hosts: the University of Leipzig, and ultimately Duke George. The duke had no real wish to provide a platform for Wittenberg’s new phenomenon and took his time to reply. It was only after the contending parties had actually arrived in Leipzig that Luther received formal permission to take part.

By this time Eck had succeeded in widening the scope of the discussion, focusing critically (and for Luther dangerously) on the issue of papal obedience. Luther had raised the matter of the historical basis of papal authority in his countertheses, greatly to the distress of several of his friends. Karlstadt, who still intended to take part in the disputation,

pointedly reasserted his obedience to papal authority. Luther, typically, made a virtue of his isolation, publishing, in advance of the debate, his research on the question of papal authority as a separate pamphlet.

21

Not surprisingly, with such a dramatic and contentious prehistory, the event itself was eagerly awaited throughout Germany. Leipzig prepared itself for the expected influx of visitors and spectators. While Eck had slipped into town unobtrusively, the Wittenberg delegation arrived together, two hundred strong, bolstered by a large number of students. Not to be outdone, Jerome Emser, a former secretary of Raymond Peraudi now attached to the court of Duke George, ensured that Eck would receive a guard of honor from the students of Leipzig on the first day of formal proceedings.

22

During the disputation the Wittenberg students made a thorough nuisance of themselves, not least with a noisy demonstration outside Eck’s lodgings, so it was something of a relief when the debate began to bore them and many slipped off home.

The debate finally got under way on June 27, though Luther only entered the lists on July 4, after Eck had debated with Karlstadt. The humanist poet Petrus Mosellanus, having delivered a lengthy opening address, went on to record his impressions of the protagonists.

Martin is of medium height with a gaunt body that has been so exhausted by studies and worries that one can almost count the bones under his skin; yet he is manly and vigorous, with a high clear voice. He is full of learning and has an excellent knowledge of the Scriptures, so that he can refer to facts as if they were at his fingers’ tips. . . . In his life and behavior he is very courteous and friendly, and there is nothing of the stern stoic or grumpy fellow about him. He can adjust to all occasions. In a social gathering he is gay, witty, ever full of joy, always has a bright and happy face, no matter how seriously his adversaries threaten him. One can see that God’s strength is with him in his difficult undertaking. . . .

Eck . . . is a great, tall fellow, solidly and robustly built. The full, genuinely German voice that resounds from his powerful chest

sounds like that of a towncrier or a tragic actor. . . . His mouth and eyes, or rather his whole physiognomy, are such that one would sooner think him a butcher or common soldier than a theologian. As far as his mind is concerned, he has a phenomenal memory. . . . In addition, he has an incredible audacity which, however, he covers up with great craftiness.

23

Luther gets very much the better of this comparison, and may, for the neutral observer, have made the more favorable impression. But there is no doubt that Eck was the more formidable debater. With wily persistence he pinned Luther back to his most controversial position, his denial of the historical roots of papal primacy. Gleefully he called attention to the most notorious progenitor of Luther’s view, the Czech heretic Jan Hus. Technically it fell to the universities of Paris and Erfurt to adjudicate the result, but rather than wait both sides rushed to place their own presentation of events in the public domain. Philip Melanchthon inevitably made Luther the victor, while Jerome Emser spoke up for Eck.

24

Emser’s contribution called for a sharp, dismissive retort from Luther, who also published his own explanations (

Resolutiones

) of his Leipzig theses.

25

Eck, for his part, offered his own account, in response to Melanchthon, and a justification against Luther.

26

Europe’s scholarly community, never so entertained nor so conspicuously in the public eye, relished every thrust and counterthrust. Leipzig’s printers, kept ceaselessly active by this rush of Latin pamphlets, reveled in their brief moment upstaging Wittenberg as the chief locus of the Reformation conflict.

Leipzig was a decisive moment for Martin Luther. It was characteristic of the man—and not always to his advantage—that he would never step back from a position once taken. Eck had pushed him further than most of his supporters would have wished on the matter of papal authority and in his affirmation that the notorious Hus had in many respects been a true Christian. As the sound and fury of Leipzig receded Luther would build these positions into the bedrock of his emerging ecclesiology. Leipzig was also a defining moment for many in the first generation of the Reformation, the point at which they defiantly affirmed the Wittenberg positions or definitively stepped back. It was also the Reformation’s first great moment of public theater. The traditional esoteric rituals of academic discourse had found a large new audience that went far beyond the theologically informed. Not just Germany, but the wider international scholarly community began to see that something very profound was stirring in the north.

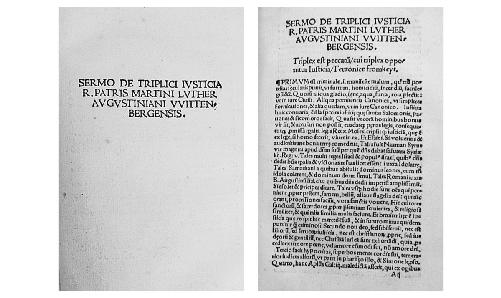

A

N

E

ARLY

L

UTHER

W

ORK

P

RINTED BY

R

HAU-

G

RUNENBERG