Brand Luther: How an Unheralded Monk Turned His Small Town Into a Center of Publishing, Made Himself the Most Famous Man in Europe--And Started the Protestant Reformation (13 page)

Authors: Andrew Pettegree

Tags: #Religion, #Christianity, #History, #Modern, #General, #Europe, #Western

Luther’s frustrations bubbled to the surface in a sermon on February 24. Preaching on the text, “Come unto me, all who labor and are heavy laden,” Luther rounded on those who sought refuge from their sins; indulgences are to be deplored because they teach us to fear punishment more than sin. Luther, whatever he thought of Tetzel, was not above a bit of theater himself. “Oh, what dangerous times! Oh, snoring priests! Oh, darkness worse than Egyptian! How careless are we in the midst of all our evils!”

44

A further sermon a few days later returned to the subject with a sustained treatment that placed at its heart the central dilemma of penance: indulgences alleviate penalties only for the truly contrite, but the contrite accept punishment rather than seeking alleviation.

Luther’s thinking developed further in the course of the summer, when he composed his first sustained writing on the subject.

45

This tract was not immediately published; its role seems to have been to help him order his thoughts for the subsequent disputation theses. Luther asked himself the crucial question that underpinned the commerce in indulgences: Could an indulgence ensure passage to heaven? His answer was an emphatic no. The imperfectly contrite have no right to indulgence; the perfectly contrite have no need of it. Here lies a hint of the radicalizing influence of Luther’s developing new doctrine of salvation.

The manuscript treatise on indulgences shows Luther shaping his views into a measured and coherent rejection of both the practice and theology of indulgences. In the autumn of 1517, by now aware that his call for a debate on Scholastic theology had gone unheeded, Luther determined to make these criticisms a public matter. This would have two strands: a renewed call for scholarly debate (the ninety-five theses), and a direct appeal to Archbishop Albrecht to rein in the excesses of the preaching being undertaken in his name.

The form of the scholarly disputation—a series of independent yet linked propositions—allowed Luther to range widely around an issue that he now clearly regarded as critical to the spiritual health of his church. Many of the theses articulated themes that he had enunciated in his earlier lectures and in the manuscript treatise of the summer, but the more provocative populist statements of the last sections reflected his genuine anger at his recent experience of the preaching of the St. Peter’s indulgence in the surrounding territories. A powerful series of ten theses replicated what he records as “the shrewd questions of the laity,” such as: “Why does not the pope empty purgatory for the sake of holy love and the dire need of the souls that are there if he redeems an infinite number of souls for the sake of miserable money with which to build a church?”

46

This topicality is one strong feature of the theses; another is the direct and unflinching way in which the developing theology of indulgences is associated directly with papal power. The pope or the papacy is directly referenced in forty-four of the ninety-five theses. Some of the more provocative we have cited already; one in particular anticipated his own later reaction to the developing crisis and the attempt to bring him to obedience:

90. To repress these very sharp arguments of the laity by force alone, and not to resolve them by giving reasons, is to expose the church and the pope to the ridicule of their enemies and to make Christians unhappy.

It was this—the decision to proceed against him by force rather than persuasion—that, more than any other consideration, would lead to Luther’s ultimate repudiation of papal authority.

T

HE

D

OOR OF THE

C

ASTLE

C

HURCH

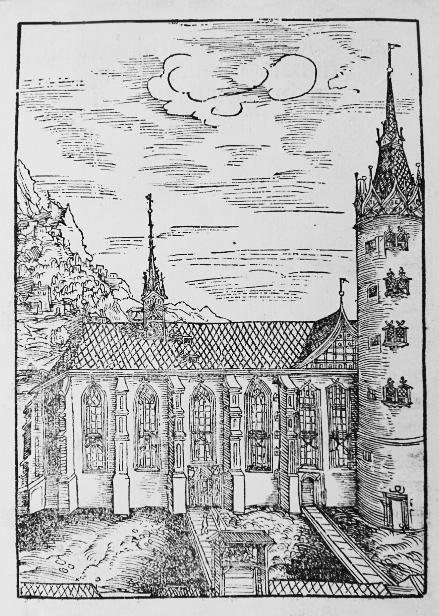

The catalog of Frederick the Wise’s relic collection contained this woodcut of the castle church. Many of the university’s classes took place here, and the door was the university’s customary billboard.

If the normal practice was followed the theses would have been sent to the university printer and set to the press. They would then have been affixed to the door of the castle church, the university’s normal bulletin board. This, according to Philip Melanchthon’s later account, occurred on October 31, less than eight weeks after the failed call for a debate on

Scholastic theology and the same day that Luther dispatched his letter to Archbishop Albrecht.

As we have seen, whether, in fact, the theses were posted in this way has been the subject of a prolonged, if rather contrived, debate.

47

It is pointed out that no eyewitness ever recorded having seen Luther at work with his hammer and nail. This is hardly surprising: the posting of formal academic documents is never a thrilling sight; no one at that point could possibly have imagined the sensational consequences. The historic record of the early part of the Reformation is often, as we have seen with the details of Luther’s early life, frustratingly incomplete. In 1516 Luther reported to a friend that he was so weighed down by correspondence that he could have kept two secretaries continuously employed.

48

Yet for the thirty-four years of Luther’s life before 1517 only forty-seven letters survive. Luther was not a famous man; his letters were not at this point worth saving. On several occasions in this book we will find ourselves discussing publications of which no one thought to retain a copy.

This was certainly the case with the first published version of the ninety-five theses if, as seems likely, it emanated from the local print shop of Johann Rhau-Grunenberg. Yet even if we lack specific contemporary documentation, the circumstantial evidence for the posting of the theses is overwhelming. We know that the Wittenberg press had been established largely to serve the interests of the university, and academic ephemera of this sort dominated the output of the first print shops.

49

We can also call in evidence the relatively recent discovery of Rhau-Grunenberg’s September printing of the theses on Scholastic theology.

50

This provides critical evidence for the existence of a Rhau-Grunenberg broadsheet prototype of the ninety-five theses on indulgences. For the earlier broadsheet Rhau-Grunenberg used what was clearly his house style, dividing the theses into blocks of twenty-five. This was precisely the form in which the Nuremberg and Basel reprints of the ninety-five theses on indulgences were presented, suggesting they were set up on the basis of a lost Wittenberg original. This really crucial

piece of evidence—the existence of a broadsheet edition printed in Wittenberg of theses proposed by Luther only eight weeks before the theses on indulgences—was unknown when the whole posting debate was initiated; one is tempted to think that if the volume in which it was discovered had been examined thirty years earlier, then this discussion would have been rendered largely redundant.

We also know that knowledge of the theses spread very quickly locally, as could only have been the case had they been exhibited publicly. Crucial evidence here is a letter to Luther of no later than November 5 from Georg Spalatin. Spalatin wrote to complain that he had not been sent a copy of the theses; clearly even at this early point they were an object of discussion at the court.

51

Finally, we have the clear statement of Philip Melanchthon, who arrived in Wittenberg a year later and was in a position to have spoken to many people who knew exactly how the controversy had begun, including Luther’s academic colleagues in the university. So almost certainly the indulgences were posted up on the door of the castle church, as the accepted narrative would have it, most probably in a now lost printed edition of Johann Rhau-Grunenberg.

So far, so ordinary. But there were a couple of circumstances that would have suggested to early observers that this would not be a mundane academic event. First, the choice of date was enormously provocative, for October 31 was the eve of the greatest day in the Wittenberg calendar, All Saints’, when the elector’s vast collection of relics was exposed to public gaze. As Luther strode through the town to affix his theses, the town would have been filling with pilgrims preparing to process through the same door where Luther’s denunciation of indulgences would soon be displayed. Luther was not naive on this point. In an illuminating retrospective commentary on the whole controversy, he revealed that he had, in fact, preached at the castle on indulgences, and the elector had made his displeasure known.

52

Frederick was, as everyone was aware, enormously proud of his church and its collections. Although the

ninety-five theses were squarely aimed at Tetzel and Albrecht, Frederick’s foe, if the elector had chosen to take offense, as well he might, Luther was finished. This is the first hint of the almost willful heedlessness that would characterize Luther’s actions in the next two years, a source of both great strength and huge peril.

For a careful academic reader the theses also held surprises. A long list of propositions does not necessarily make a coherent argument; this is not the point. But the shift in voice, the mix of carefully considered general propositions and blisteringly direct utterances placed in the mouth of the laity, was very unusual for what purported to be a formal academic exercise. The effect was rather discordant. When subjected to close examination by unsympathetic authorities the theses would have exuded a distinct whiff of danger; the demotic explosions gave many hostages to fortune. Clearly many of the first readers did not quite know what to make of this. Luther, looking back on these events, did not take any great pride in the ninety-five theses. Had he had any sense of their likely impact, he told a later correspondent, he would have taken far more care with them.

For now, Luther was keen to give the theses the widest possible circulation. As with the theses on Scholastic theology, copies of Rhau-Grunenberg’s printed version were dispatched to his usual circle of friends, with the request that they circulate them further. But first he had a letter to write to Albrecht of Brandenburg. Although couched with a degree of the deference appropriate to their two very different stations in life, the letter is remarkably forthright. After cursory compliments Luther comes straight to the point:

Under your most distinguished name, papal indulgences are offered all across the land for the construction of St. Peter. Now, I do not so much complain about the quacking of the preachers, which I have not heard; but I bewail the gross misunderstanding among the people which comes from these preachers, and which they spread

everywhere among common men. Evidently the poor souls believe that when they have bought indulgence letters they are then assured of their salvation.

53

In this letter Luther focused his criticism on the printed instructions for the preaching of the indulgences, which Luther asked Albrecht to withdraw.

54

He enclosed a copy of his manuscript treatise on indulgences, and almost as an afterthought (he mentioned it only in a postscript), the ninety-five theses.

55

The weeks stretched by without reply. This was not entirely Albrecht’s fault. Luther’s letter was probably dispatched first to Magdeburg. Remarkably, the original survives, so we know it was only opened on November 17, and then sent on to Albrecht at his palace in Aschaffenburg.

56

He seems not to have been aware of it before the end of November, by which time news of the proposed disputation in Wittenberg was circulating quite widely.

Albrecht was already not in the best of tempers. The receipts from the preaching of the indulgences had thus far been quite modest, and certainly far from sufficient to meet his obligations to Rome and his bankers. The refusal of Frederick the Wise to allow the indulgence to be preached in his lands was already a provocation; then came this presumptuous attack from one of Frederick’s professors. In the circumstances, the archbishop’s response was remarkably measured. On December 1 he passed Luther’s communication to the Theology Faculty at Mainz with the request for an opinion; he wrote again on December 11 to urge the doctors to make haste. The answer when it came was a masterpiece of equivocation. The Mainz theologians defended the right of the University of Wittenberg to stage such disputations. At the same time they felt that issues of this sort were best left to the pope. Albrecht did the sensible thing and forwarded the theses to Rome.

Luther, meanwhile, was doing what he could to make the theses known. He wrote to his diocesan bishop, the bishop of Brandenburg, who advised him to leave the whole issue alone. Otherwise his

correspondents were familiar friends, Lang in Erfurt and Christoph Scheurl in Nuremberg. Scheurl in particular responded enthusiastically, sharing the theses with friends in the city patriciate and intellectual community.

57

Scheurl may also have taken a role in arranging for the theses to be reprinted in Nuremberg, an absolutely decisive step in ensuring their wider public impact. Further editions were published in Leipzig and Basel. These were a study in contrasts. The Leipzig edition (probably based on an unofficial manuscript copy) was muddled and misnumbered: a reader would have thought Luther had written eighty-seven theses.

58

The Basel edition, in contrast, was a neat and elegant pamphlet, like the Nuremberg edition dividing the theses into three groups of twenty-five and one of twenty. In keeping with Basel’s reputation as a sophisticated cultural capital the numbering was in Roman numerals. With this pamphlet Luther’s theses entered the bloodstream of the European intellectual community. It was this edition that, in March 1518, a curious Desiderius Erasmus sent to his great friend Thomas More in England.

59