Brand Luther: How an Unheralded Monk Turned His Small Town Into a Center of Publishing, Made Himself the Most Famous Man in Europe--And Started the Protestant Reformation (12 page)

Authors: Andrew Pettegree

Tags: #Religion, #Christianity, #History, #Modern, #General, #Europe, #Western

It was only in the course of his last great campaign that Peraudi seems to have sensed a significant ripple of dissent. In March 1502 he lashed out angrily against “murmurers and detractors.” The cardinal was sufficiently riled to defend the theology of indulgences in an open letter.

This seems to have been sufficient, and the results of the campaign were certainly spectacular: a reputed four hundred thousand gulden for papal coffers.

26

Peraudi’s death brought a subtle change. In the second decade of the sixteenth century a number of respected and influential figures began to express reservations about the apparently relentless sequence of fund-raising ventures. In Würzburg, Constance, and Augsburg, local clergy warned against the dangers of the substitution of indulgence for true penance.

27

Most eye-catching was the intervention of Johann von Staupitz, Luther’s first patron and a senior figure in the Augustinian order. In a series of sermons preached at Nuremberg during Advent 1516, Staupitz condemned the excesses of indulgence preachers in terms that would find many echoes in Martin Luther’s later writings. In the early months of 1517 these much admired sermons were published in both Latin and German.

28

These criticisms were not confined to Germany. In the Reformation narrative the Theology Faculty of the University of Paris, the Sorbonne, is normally cited as a bastion of orthodoxy, but in March 1518 it, too, expressed its reservations about indulgences. The Sorbonne censured the proposition that “whoever puts a teston, or its value, in the crusade chest for a soul in purgatory, frees the said soul immediately.”

29

This phrase offers a remarkably close echo of the infamous jingle cited by Luther, and apparently something of the sort had been circulating in Paris since the 1480s.

The churchmen who now made their reservations known seem to have been emboldened by a rising tide of criticism among Germany’s rulers. Although happy to petition the pope for indulgences for their own purposes, local authorities certainly recognized the potential damage if huge quantities of specie were withdrawn from the local economy to be sent to Rome. All early modern societies were cash poor; many everyday financial transactions were conducted by barter.

30

Indulgence certificates, however, had to be paid for in coin, and this resulted in large sums being taken out of the German economy. These concerns were laid bare in a spectacular altercation between Peraudi and the Emperor Maximilian, a rare occasion on which the proud cardinal was comprehensively worsted.

31

During the course of Peraudi’s last campaign the emperor had made plain his intention to retain in Germany a greater share of the monies raised by Peraudi’s industry. The cardinal was appalled and took to print to denounce this violation of his papal privilege.

32

But Maximilian was unmoved; the money was not released. Repeated attempts to shame Maximilian into compliance achieved nothing and Peraudi was ultimately forced to retreat to friendly Strasbourg for fear Maximilian might be goaded to reprisals by the intemperance of his press campaign.

S

ILVER

T

HALER OF

F

REDERICK THE

W

ISE, 1522

Early modern Europe suffered from an acute shortage of specie, particularly of coins in small denominations. While many transactions relied on barter and credit, indulgences could only be paid for in cash, draining money out of the economy.

Other German authorities took note. In 1516 the imperial free city of Nuremberg found itself simultaneously resisting the promotion of the Empire-wide Holy Spirit indulgence, while appealing to the pope for a new indulgence for its own church. This may not impress in terms of intellectual consistency, but the council’s explanation of their opposition was a significant straw in the wind: they regarded the pope’s indulgence, they said, “more as a deception of the common folk, than serving as

nourishment for their souls.”

33

Here the council was responding to an unmistakable sense of indulgence fatigue. There is some indication that this may have set in as early as Peraudi’s last campaign, though the evidence is ambiguous. In Nuremberg receipts fell by a third between the campaigns of 1488 and 1502, though in Strasbourg they registered a modest increase (here, as elsewhere, receipts were most buoyant where Peraudi preached in person). By the second decade of the sixteenth century the trend was unmistakable. The great city of Speyer had contributed 3,000 gulden in 1502; the campaign of 1517 raised just 200. In Frankfurt in 1488 Peraudi had raised 2,078 gulden; in 1502 he grossed just half of this; the St. Peter’s indulgence of 1517 brought in a mere 304 gulden.

34

The problem was fairly clear. With repeated campaigns over almost thirty years for both local and international causes, most pious souls had by now purchased the precious certificates and were, therefore, reluctant to fork out again. This problem was recognized in the papal Curia, and brought forth an unpopular and highly controversial resolution: with the promulgation of each new indulgence, previous grants were suspended and the effectiveness of previously purchased indulgences placed in abeyance. In the case of the St. Peter’s indulgence this hiatus was set at eight years.

35

For those close to death, or who looked to the assurance of previous pious investment, this was especially bitter. Resentment at this maneuver was specifically alluded to in Luther’s eighty-ninth thesis: “Since the pope seeks the salvation of souls rather than money by his indulgences, why does he suspend the indulgences and pardons previously granted when they have equal efficacy?”

36

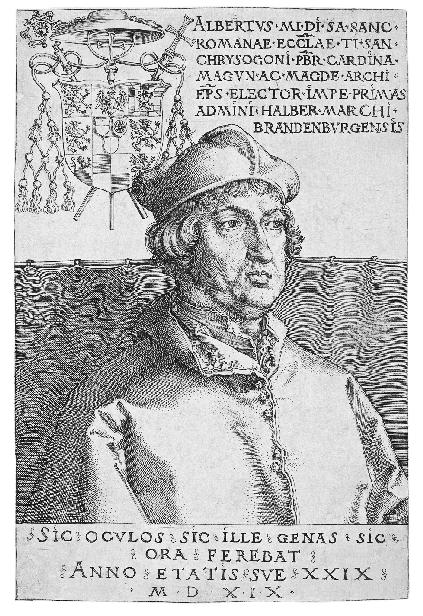

The effect of these incremental grievances was not lost on those charged with promoting new indulgence campaigns, among them Albrecht of Brandenburg, archbishop of Magdeburg and newly promoted archbishop of Mainz. It was the sordid financial transaction underlying this promotion that added gas to the fire lit by Luther. In return for one of Germany’s richest ecclesiastical prizes, and for permission to hold the two sees simultaneously, Albrecht would pay the pope twenty-three thousand ducats, a huge sum. To help Albrecht meet this obligation it

was agreed that half of the proceeds of preaching the St. Peter’s indulgence in his diocese could be set against this debt.

A

LBRECHT OF

B

RANDENBURG,

P

RINCE OF THE

C

HURCH AND

P

ATRON OF

A

RT

It was this print that Dürer sent to Cranach as a possible model for his portraits of Luther. Despite their differences Albrecht retained a sneaking regard for Luther, sending him a generous gift on his marriage in 1525.

One did not have to be a radical critic of the church to believe that with this transaction the commerce of devotion had gone too far. Albrecht, in fact, agreed, and his initial instinct was to refuse.

37

He was under no illusions as to the difficulties he would face in raising this

money in a part of Germany that had witnessed two major indulgence campaigns in the previous five years. At least the money raised in these instances had been for German causes, whereas in the case of the St. Peter’s indulgence all the money would be sent to Rome. Surely the pope should look to his own resources; or, as Luther put it in the remarkably bold and tactless thesis number eighty-six:

Why does not the pope, whose wealth is today greater than the wealth of the richest Crassus, build this one basilica of St. Peter with his own money, rather than with the money of poor believers?

38

Albrecht’s misgivings were fully justified. Perhaps he should have shown the prudence of another German prince, Albrecht of Brandenbach-Ansbach, who when offered a similar bargain refused point blank to be involved. It was clear, he replied, that the St. Peter’s indulgence was not popular among the common folk.

39

More telling still was the refusal of the German Observant Franciscans to undertake preaching of the indulgence. The Franciscans were the order traditionally associated with indulgence preaching, and on this occasion they were specifically tasked by Leo X to work with Albrecht of Mainz in the organization of his campaign. But this assignment was declined. According to Friedrich Myconius, then a member of the order, the indulgence was too associated in the public eye with “Roman luxury.” Albrecht was forced instead to turn to the Dominicans, contracting with the fifty-year-old Johann Tetzel to lead his campaign. It would prove to be a fateful choice.

THE CHURCH DOOR

As we have seen, indulgences were not a major concern of Luther’s during his first busy years in Wittenberg. They rate only occasional treatment in the course of his two major lecture series between 1513 and 1516. In the lectures on the Psalms in 1514 Luther refers to indulgences

as one of the means by which people are led to believe that the Christian life is easy; he criticizes churchmen for their willingness to take part in the trade.

40

By the time of the lectures on Romans in 1516, as was typical of the series as a whole, Luther is more trenchant and hard-hitting. Now he condemns indulgences as ostentatious and meaningless works that lead to neglect of the unglamourous works of Christian charity. For the first time he also offers pointed and direct criticism of the Church hierarchy: “The pope and the priests who are so generous in granting indulgences for the temporal support of churches are cruel above all cruelty, if they are not even more generous or at least equally so in their concern for God and the salvation of souls.”

41

Despite this ominously direct language, it was only in 1517 that Luther began to engage with the issue in any sustained way. For now his Wittenberg congregation was beginning to experience at firsthand the impact of Tetzel’s campaign in the diocese.

The St. Peter’s indulgence was never, in fact, preached in Wittenberg, or indeed in Electoral Saxony, since the elector withheld his consent. This was not because Frederick had been persuaded by the criticism of indulgences, but for baser financial considerations. The sale of indulgences was likely to diminish the impact of his relic collection, which by now carried a dazzling panoply of spiritual benefits; in addition Frederick saw no reason to oblige Albrecht, a member of the rival house of Hohenzollern, not least because the bishopric of Magdeburg, to which Albrecht had been appointed, had previously been occupied by members of his own family.

So Tetzel stayed out of Saxony. But when he preached at Zerbst and Jüterbog he was close enough to its long, straggling border for citizens of Wittenberg to go and hear him, returning with the precious certificates.

42

Luther was apparently riled when in confession proud owners showed him their certificates and asked for lighter penances. He would also have been deeply troubled at reports of the unrestrained manner in which the indulgence was preached, throwing off all subtlety in the search for souls. The text of one sermon attributed to Tetzel tells its own story:

You priest, you nobleman, you woman, you virgin, you married woman, you youth, you old man . . . [r]emember that you are in such stormy peril on the raging sea of this world that you do not know if you can reach the harbor of salvation. . . . You should know: whoever has confessed and is contrite and puts alms in the box, as his confessor counsels him, will have all of his sins forgiven. . . . Do you not hear the voices of your dead parents and other people, screaming and saying: “Have pity on me, have pity on me . . . for the hand of God hath touched me” (Job 19.21)? We are suffering severe punishments and pain, from which you could rescue us with a few alms, if only you would.

43