Brand Luther: How an Unheralded Monk Turned His Small Town Into a Center of Publishing, Made Himself the Most Famous Man in Europe--And Started the Protestant Reformation (7 page)

Authors: Andrew Pettegree

Tags: #Religion, #Christianity, #History, #Modern, #General, #Europe, #Western

At the time of Luther’s birth Hans was preparing to embark on an ambitious but potentially perilous enterprise.

5

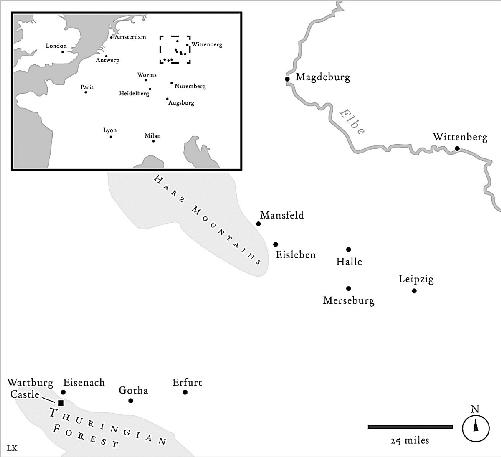

In 1484 he would move his young family to Mansfeld, further up in the Harz Mountains, where Hans intended to try his hand in the mining industry. At this time the county of Mansfeld boasted some of the richest seams of copper in all of Europe. The copper ran in a thick rib through the hills, sometimes close to the surface, sometimes many hundreds of feet below. The extraction and smelting of this precious metal required both skill and substantial investment, and at this point the mines of Saxony and Thuringia were attracting investment capital from some of Germany’s most substantial banking and merchant families. Hans Luter (as the family name was then given) did not have this sort of money, and he was forced to borrow heavily to set himself up.

L

UTHER’S

W

ORLD

This was a lucrative but precarious trade. A seam of copper could plunge impossibly deep, a mine could collapse or flood. It was a hard, dangerous life, requiring strong nerves even of those who, like Hans, remained above ground. Since he leased rather than owned the mining rights, he could only operate his mines and furnaces by continually renewing lines of credit.

6

The family remained heavily exposed throughout his life, and Hans only finally paid off his debts in 1529, the year before his death. So although his business flourished—he was elected to the Mansfeld city council, and the family lived well—this prosperity was fragile. The young Luther would have learned both the great gains to be won by industry, and their unpredictability.

The importance of this unusual background, at a time when very few of Europe’s population were engaged in primary industries such as mining, is not always recognized in studies of Luther’s intellectual formation. In later life Martin would recall a household where parenting was strict and children were taught the value of money. But attempts to interpret the crucial turning points of Luther’s life as a reaction against a cold and distant father, or mother, tell us more about the era in which they were written (the 1960s and 1970s) than about Luther.

7

Martin was conscious that he came from a loving home; he honored his parents and in turn would be a devoted and doting father. But in an age when industry was in its infancy, few academics would have experienced so closely the particular context of life in a household dependent on the golden harvest of precious metals. This experience would stand Luther in good stead when in his middle years he interested himself in another fledgling industry requiring strong nerves and heavy investment, the printing trade. When Luther walked into a printing shop, he did not do so as the naive academic who imagined that the creative process ended with the completion of his manuscript, but as a practical man, well-grounded in the harsh economics of profit and loss, and the disciplines and dangers of a business run on credit. This would be, from the standpoint of the Reformation, a lesson well learned.

For the moment the Luters prospered. Although the family

continued to grow (Martin was one of eight children, though only four lived to adulthood), there was enough money left to send Martin to school. His education probably began at the local

Trivialschule

in Mansfeld. By the age of thirteen he had made sufficient progress with his letters to be sent away to school, for a year in Magdeburg, then to Eisenach. Here he was under the supervision of his mother’s family, and Martin would remember these as happy years. By 1501, just short of his eighteenth birthday, he was ready to make the relatively short journey to Erfurt, to be enrolled in the university. It was at this point that an extra letter was added to the family name, and Martin became Luhter, and later Luther.

L

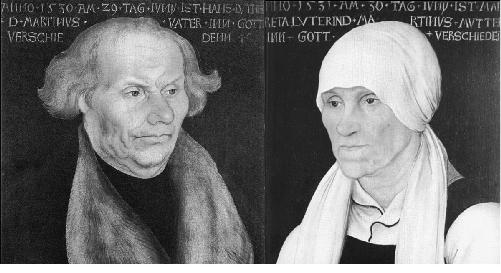

UTHER’S

P

ARENTS

Painted by Lucas Cranach toward the end of Luther’s parents’ lives, these pictures capture the impact of a long tough career in the mining industry. Though his upbringing was strict, young Martin was the product of a loving home, and always remembered it as such.

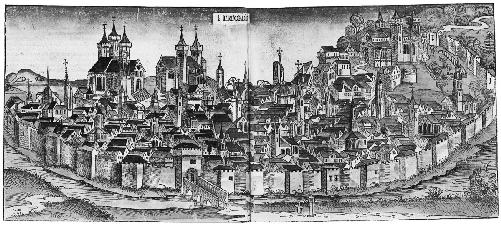

At this time Erfurt was a large and thriving city, one of the largest and most sophisticated in northern Germany. Its population of twenty thousand was served by more than one hundred ecclesiastical institutions: as much as 10 percent of the population were monks, priests, or nuns. The two thousand students who attended the university found lodging around the town or, in the first years, in dormitories in the university’s own quarters.

Erfurt was the largest place in which Luther had ever lived, and he took a little time to find his feet. At the end of his first year he was ranked thirtieth in a class of fifty-seven, but by the time he completed his MA in Liberal Arts he ranked second in a class of seventeen.

8

Now, at the insistence of his father, Luther applied himself to the study of law. There was never any question that Martin would follow his father into the mining business. For his clever son, Hans had in mind a profession that might lead to lucrative fees, perhaps even a place in the administration of one of the region’s princely courts and a career of distinction and influence. Martin dutifully supplied himself with the necessary texts, but it soon became clear that he had no taste for this new life. Within a few months he had abandoned his father’s careful plan, sold his law books, and applied to join the local chapter of the Augustinian Hermits, the so-called Austin Friars.

This first turning point in his life was one for which Luther did, in years to come, provide a detailed explanation. As the story goes, Luther was returning from a visit to family in Eisenach when, four miles short of Erfurt, he was caught in a thunderstorm. The terrified Luther feared for his life and swore that if he was spared he would abandon the world for the monastic life. Two weeks later he was as good as his promise.

There is no reason to doubt the essence of this narrative, but it is unlikely to be the whole truth. For four years Martin had lived in an atmosphere saturated with the religious culture of one of Germany’s richest ecclesiastical cities and its university. He had proved an apt pupil, and dry legal texts held no appeal. The inescapable calling, the unanswerable intervention of an all-knowing deity, resolved a career dilemma with which Luther had probably been struggling for some time. The unmissable allegory of the most powerful conversion narrative of the New Testament, Saul on the road to Tarsus, also provided a means to short-circuit awkward discussions with a pious but understandably furious parent who had invested so heavily in a brilliant future for his son.

9

In the event, the breach between the two was of short duration. When Martin was ordained a priest in Erfurt in 1507, his father made a rather ostentatious

appearance, accompanied by twenty mounted companions. He also made a substantial donation to the Erfurt Augustinian house.

E

RFURT

One of Germany’s great cities, and the largest place in which Martin Luther ever lived.

Luther had opted for a hard and austere life, a life of constant study punctuated by the monastic round of frequent collective prayer, the daily offices. He slept in a small, unheated cell, ten feet by seven, equipped only with a straw bed; further decoration was forbidden. Coping with the transition from the gregarious, companionable aspects of student life was not easy, and Luther experienced periods of self-doubt and low spirits that would continue to afflict him intermittently throughout his life. But he accepted obediently the life he had chosen, and it was not long before his evident talent marked him out for offices of responsibility within his house and order.

Life in the Erfurt Augustinian monastery may have been hard, but the institution was also rich, well-endowed with property and possessed of a fine library. It also maintained close links with the university, where Luther was able to continue his theological training. From 1502 the Erfurt Augustinians had also begun to develop connections with the newly established university in Wittenberg. To add luster to the new institution, Frederick the Wise had been keen to secure the assistance of

Johann von Staupitz, a rising star of the order and from 1503 vicar of the German Reformed chapter of the Augustinian Hermits. From 1503 Staupitz was formally seconded to Wittenberg as the university’s first professor of biblical theology. Staupitz was also heavily involved in encouraging other Augustinian houses to adopt the austere standards that characterized Erfurt and those houses that had adhered to reform. He would be the first of a number of influential public figures who would play an important role in promoting Luther’s career. When, in 1508, the lecturer in philosophy at Wittenberg took a brief sabbatical to prepare for academic promotion, it was Luther whom Staupitz summoned to fill the vacancy.

This unlooked-for promotion caused Luther some difficulties on his return to Erfurt the following spring. Staupitz’s efforts to recruit the other Augustinian houses in Germany to the cause of reform were proving increasingly controversial. In 1507 a way forward was proposed whereby the reform congregations would merge with other houses of the Saxon province. This could be interpreted as either a great victory for Staupitz or a possible dilution of the reforming agenda; the members of Luther’s Erfurt house chose to take the latter view. Two delegates, Johann Nathin and Luther, were dispatched to Rome to plead this case. This journey, in 1510–1511, was the longest Luther ever undertook, and it made a deep impression on the young monk. Even before crossing the Alps, he passed through some of Germany’s most wondrous cities, Nuremberg, Ulm, and Memmingen. In Italy the two brothers journeyed on via Milan, Siena, and Florence. But it was the glories of Rome, its churches and places of pilgrimage, that most attracted Luther’s admiration. For Luther, Rome represented an unexpected opportunity to celebrate his church in the fountainhead of its authority; his instinct was to take full advantage of the spiritual benefits offered by Rome’s numerous sites of special indulgence. His parents were still alive, so Martin could do nothing for them, but Luther gladly scaled the Santa Scala on his knees to free his grandfather from purgatory. Luther’s experience of Rome also left a certain ambivalence. He was shocked at the casual

cynicism he witnessed among Rome’s enormous clerical population; the sheltered life he led in Erfurt’s reformed house had not prepared him for the experience of hearing priests cracking jokes about the Eucharist. Luther’s impressions are confirmed by another visitor, Erasmus of Rotterdam, who had visited Rome five years previously. “With my own ears,” Erasmus would recall, “I heard the most loathsome blasphemies against Christ and his apostles.”

10

These more negative recollections would return to Luther in later years, when his writings brought him into conflict with the pope. For the moment, though, he was more concerned with the mission on behalf of his order, which had achieved nothing, so on Luther’s return Staupitz attempted to settle the question by negotiation. An agreement was reached that would preserve the special status of reformed institutions while largely absorbing the other houses. Presented to the reformed houses for ratification, a majority of the Erfurt brothers still favored rejection; but Luther joined a minority that supported Staupitz. Luther’s decision to follow his patron rather than the majority of his own house was a hard one, and it cast a shadow over relations within the cloister that never really lifted. In these circumstances a further period in Wittenberg presented a tactful opportunity to allow tempers to cool. Luther was not to know that the Augustinian house in Wittenberg would be his home for the rest of his life.