Brand Luther: How an Unheralded Monk Turned His Small Town Into a Center of Publishing, Made Himself the Most Famous Man in Europe--And Started the Protestant Reformation (15 page)

Authors: Andrew Pettegree

Tags: #Religion, #Christianity, #History, #Modern, #General, #Europe, #Western

Luther had Tetzel’s work in his hands very quickly. Branding it (quite unfairly) “an unparalleled example of ignorance,” he set about a reply. This second pamphlet was, again, extremely succinct, and another publishing success, with nine editions in 1518.

68

Tetzel’s

Rebuttal,

in contrast, largely failed to find an audience. The first edition was not reprinted; for his further and last contribution to the debate he reverted to Latin. This work Luther simply ignored.

Tetzel was by this point a much diminished figure: tired, humiliated, and ill. For his own protection he had taken refuge in the Dominican house at Leipzig; the public had turned against him and his career as an indulgence salesman was at an end. So, too, was his usefulness to the Catholic Church. Although his local Dominican brethren continued to offer him sanctuary, the church hierarchy preferred to throw him to the wolves. When the pope’s delegate Karl von Miltitz came to Germany in the autumn of 1518 to attempt a solution to the Luther problem, he made it abundantly clear that Tetzel was expendable, that he was prepared to “butcher the black sheep.” By denouncing the commissioner’s excesses and irregularities, the doctrine of indulgences could perhaps survive unscathed. In a personal interview in Leipzig the aristocratic von Miltitz subjected Tetzel to a calculated public humiliation.

That meeting would be Tetzel’s last appearance on the public stage. He died in July 1519, broken and defeated. In the years that followed, the

reformers continued to heap opprobrium on a man whose career conveniently symbolized the worst excesses of the indulgence trade; few voices were raised in his defense. Later Luther would rather shamefacedly claim that he had written to Tetzel in his last days to offer him spiritual comfort. If this is the case, the letter has not survived.

The Reformation would make and break many reputations; in due course the conflicts and passions generated by the division of the churches would claim many lives. But there is little doubt that Johann Tetzel, theologian and defender of indulgences, was its first

victim.

4.

T

HE

E

YE

OF

THE

S

TORM

N THE TWO YEARS

N THE TWO YEARS

1518 and 1519 Luther’s world changed out of all recognition. He became a public figure. He became, to his distress, the enemy of the church he had served so faithfully for his first thirty-five years. He began to attract passionate devotion beyond the small number of intimates who had thus far shared his cause. And he became a best-selling author.

It was during these years that Germany’s rulers were gradually awakened to the potentially momentous consequences of the

causa Lutheri,

the Luther affair. Luther, meanwhile, met every twist and turn of the gathering controversy with new theological revelation. For two years he wrote and wrote. German readers devoured every work; each new text was instantly reprinted and sold in huge numbers. Wittenberg’s fledgling printing industry struggled to keep pace. That, too, was a problem that had to be addressed.

These were also years when Luther was obliged to travel out of Wittenberg very frequently—more than he would ever do in his life again. In the three years between March 1518 and March 1521 Luther undertook three long and demanding journeys, to Heidelberg, Augsburg, and Worms, as well as shorter but still stressful trips to Leipzig and Altenburg. The trips to Augsburg and Worms were undertaken at considerable

peril. To protect him from likely papal retribution it had been necessary to obtain safe-conducts, but neither Luther nor his anxious friends could be certain these would be honored.

These journeys were also of great importance to the development of Luther’s public persona. Luther was on the road for several months. He covered most of the almost three hundred miles to Heidelberg on foot, staying with friends and in Augustinian houses. The journey to Worms three years later was undertaken in very different circumstances and became the occasion for dramatic demonstrations, as a fascinated public scurried to catch a glimpse of the notorious heretic friar, and supporters orchestrated noisy demonstrations in his favor. Crucially, in all of these travels the way stations along the route provided the opportunity for Luther to make his case, initially on indulgences, later on other aspects of his developing theology. He sat down with sympathetic members of his order, senior theologians who could not be persuaded, and curious and influential patrician intellectuals like Willibald Pirckheimer. Most of these conversations involved people meeting Luther for the first time. Many remembered it as a life-defining encounter with an exceptional mind and an extraordinary personality.

The strain on Luther must have been intense, as he was introduced to a bewildering variety of new friends and potential allies at the end of an exhausting day on the road. We must remember, too, that many of these conversations were undertaken under the shadow of the looming ordeal of a formal audience in hostile territory that had the potential to end his career and his incipient movement. That he conducted himself with such cool confidence is, in the circumstances, extraordinary, as indeed was his physical and mental stamina. Luther had to grow very quickly, not least as he adapted to carrying the hopes and expectations of the increasing numbers who had committed themselves to his cause. As with his blossoming activity as a writer and public theologian, this was another challenge for which Luther’s previous life had provided little preparation. But all of these encounters played a critical role in building the Reformation.

ROME

In 1518 responsibility for settling the Luther affair moved to Rome.

1

The Curia was aware of Luther’s criticisms of indulgences by January 1518, and from this time on German matters loomed increasingly large in the pope’s calculations. The fact that it would take a further two years before Luther’s definite condemnation may give the impression of slow deliberation, even indecision and delay. This was not really the case. The Curia was immediately aware of the need to shut down Luther’s protest. But this had to be done in such a way as not to inflict further damage on the indulgence trade, if possible with the full cooperation of the local powers. This was seen, therefore, as much as a diplomatic as a theological problem. And here lay the difficulty. It was relatively easy to recognize the dangers in Luther’s criticisms of indulgences, and to reaffirm traditional teachings. It was quite another matter to lay hands on him.

In this dilemma lay the key to the very different approaches to the events of 1518 and 1519 favored by Luther’s opponents and his friends. In Rome it was immediately clear that it would be best if the resolution of the Luther affair could be conducted through diplomatic channels, and behind closed doors. It followed, equally, that Luther’s best chance of survival lay in ensuring that his cause remained in the public eye. The oxygen of publicity was, quite literally, a matter of life and death.

Given Luther’s criticisms of the papacy in his ninety-five theses, it was inevitable that Rome would be the proper locus of judgment in his cause. It was sensible, therefore, for Albrecht of Brandenburg to forward to Italy the bundle he had received, written as he put it by “an impudent monk of Wittenberg.” This summary and rather contemptuous judgment set a bleak tone for the Roman procedures against Luther. There was never any possibility that the papal authorities could have acceded to Luther’s demands for a radical rethinking of the teaching on indulgences. To have suspended, or in any way undermined, the preaching of the St. Peter’s

indulgence at such a time would have ruined Albrecht, and fatally weakened the economy of the church. It was unlikely such a possibility was ever seriously considered. The earnest writings of an unknown Augustinian and a call to debate in a distant and obscure university hardly constituted a significant threat. The Roman Curia had adequate procedures for dealing with such minor squalls; there was nothing to suggest that the impudent monk would have been more than a minor item in a crowded agenda.

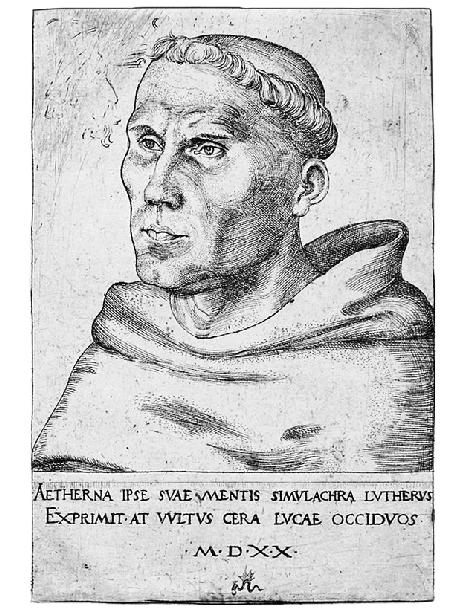

L

UTHER IN 1520

The first of Cranach’s iconic portraits of the reformer, this was deemed too confident and provocative for public circulation.

The Luther materials were passed to Silvestro Mazzolini, known as Prierias, a capable theologian (and a Dominican), to judge. But even before he had a chance to examine them, the pope dispatched a letter to Gabriele della Volta, general of the Augustinian Hermits, requesting him to take measures to silence Luther. Della Volta was in Venice, so passed

the instruction to the German regional superior, who was, of course, Luther’s friend and patron Staupitz. It was only in May, when it became clear that the German Augustinians would not cooperate, that the process in Rome moved forward. Prierias was now asked to prepare an opinion. According to his later rather incautious boast, it took Prierias only three days to determine that Luther’s theses were heretical. In the matter of indulgences it fell within the authority of the church to establish true doctrine; therefore: “Whoever says regarding indulgences that the Roman church cannot do what it

de facto

does, is a heretic.”

2

On the basis of this opinion Luther was summoned to Rome to answer for his opinions. This judgment was communicated to Luther in Wittenberg in early August; he also had access to Prierias’s determination, which had been published as a pamphlet in Rome and swiftly reprinted in Augsburg and Leipzig.

3

It was immediately clear to Luther that to obey this summons would have been potentially fatal. Happily, the stars had aligned to make such an outcome improbable. In August the assembly of the German nation, the Imperial Diet, had gathered in Augsburg. Here they were joined by the pope’s representative, Tommaso de Vio, Cardinal Cajetan. Cajetan would be one of the most interesting figures to engage himself with Luther. Although another Dominican, which Luther did not find reassuring, he was an exceptionally gifted theological thinker, measured and unflappable. He was also far from being an uncritical admirer of indulgences. Cajetan had actually addressed the issue in an important treatise, written at the invitation of a fellow cardinal (Giulio de’ Medici, the future Pope Clement VII). While avoiding any mention of the issue of papal authority, Cajetan made clear that he wished to rein back the exuberant growth of indulgences. He frankly recognized that they were not to be found in Scripture or the church fathers. The re-creation of a true doctrine of penitence would have no need of them.

4

So while Cajetan came to Augsburg as the pope’s agent, he was far from being an uncritical advocate of the status quo. He would also have been made aware of the mutinous temper of the German Estates, faced with new financial demands to combat the ever-present Turkish threat.

5

Cajetan was swiftly convinced that Luther should be heard in Germany, not Italy, and this recommendation was transmitted to Rome.