Brand Luther: How an Unheralded Monk Turned His Small Town Into a Center of Publishing, Made Himself the Most Famous Man in Europe--And Started the Protestant Reformation (14 page)

Authors: Andrew Pettegree

Tags: #Religion, #Christianity, #History, #Modern, #General, #Europe, #Western

The dissemination of the ninety-five theses took Luther into uncharted waters; the same, to a considerable extent, was true of the printing industry. In the course of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries Europe’s printers would put out many thousands of academic disputations. The publication of dissertation theses was an essential part of progress to any higher academic degree, and very few had a purpose or value that lasted beyond this formal academic occasion. If they survive, they are seldom consulted today. In fact, academic libraries possess many thousands of these dissertations that have never actually been cataloged.

This sort of academic ephemera seldom attracted any notice outside the university where the disputation took place; I am struggling to think of any examples where dissertation theses found a sufficient audience to merit a new edition elsewhere. Yet in Luther’s case his theses on indulgences were reprinted three times, in three separate cities, including one (Nuremberg) that did not have a university. According to Luther’s correspondents the Nuremberg press also published the theses in a German translation, though if this was the case no copies have survived.

60

This,

again, would be totally unprecedented. Something very unusual was going on.

T

HE 95

T

HESES

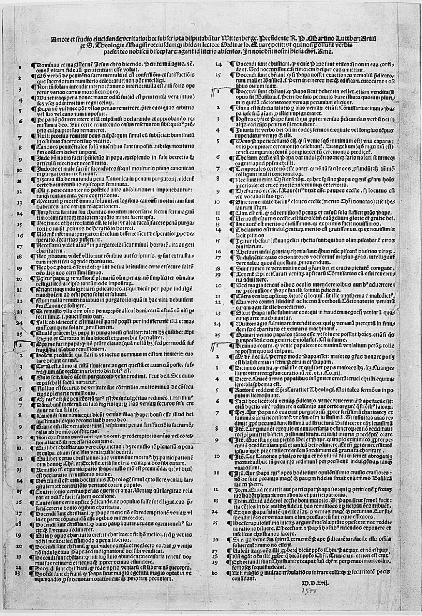

Here in the broadsheet edition published in Nuremberg by Hieronymus Höltzel (USTC 751649), note the division of the theses into three groups of 25 and one of 20, presumably following the model of the lost Rhau-Grunenberg original.

Martin Luther certainly thought so. “What is happening is unheard of,” he told a correspondent in May 1518, and he was certainly correct. The printing of the ninety-five theses had given them a new life, totally separate from the planned disputation, which, of course, never took place. This restricted academic event was now completely forgotten, for thanks to print the indulgence controversy had become a public matter. And not all who read the text could afford to allow Luther’s criticisms to go unanswered.

TETZEL

In all the many thousands of books written about the Reformation, virtually no one has had a good word to say about Johann Tetzel, Albrecht of Mainz’s commissioner for the sale of indulgences in the diocese of Magdeburg. Tetzel is the pantomime villain of the Reformation: frequently portrayed as crude and unscrupulous, prepared to make the wildest of claims to extract money from the credulous. This is something of a travesty. Tetzel was certainly flamboyant and a showman, but then so, too, was Raymond Peraudi; so were many of the great medieval preachers who drew vast crowds on their peripatetic preaching tours. He was an educated man, and a sophisticated and thoughtful theological writer, as the indulgence controversy would prove. He was also good at his job. And while his superiors were slow to react to Luther’s challenge, Tetzel recognized the seriousness of the threat. He was the first to articulate a response to Luther’s criticism, earning further abuse for his pains. Tetzel was savagely treated partly because Luther and his friends recognized him as a formidable adversary; which is why they set out to destroy him.

Tetzel’s appointment as indulgence salesman was hardly a desperate last resort for Albrecht. Although Albrecht had been disappointed in

obvious candidates to lead the indulgence campaign, Tetzel offered a wealth of relevant experience. He was educated at the University of Leipzig and had taught theology at the Dominican school in the city. Since 1509 he had been the inquisitor, or master of heretics, for Poland. He also had considerable experience in the preaching of indulgences. Not surprisingly, given the lack of enthusiasm of other candidates for the position, Tetzel could command a decent salary for his services. He was paid a stipend of eighty gulden a month, a considerable sum; in addition he and his subcommissioners claimed expenses of three hundred gulden a month. Albrecht complained angrily at this lack of economy, but given the frenetic pace of Tetzel’s itinerary, and the distances covered, it is hard to see how this could have been achieved without cost.

Tetzel was also at the heart of the first coherent effort to rally conservative forces against Luther. This occurred at a meeting of the Dominican chapter in Frankfurt-an-der-Oder, home to the new university of Electoral Brandenburg. In a demonstration of support for their Dominican brother, a series of theses were prepared in defense of indulgences, to be debated by Tetzel. As was often the custom in Germany the theses were written by someone else, in this case Konrad Koch, known as Wimpina, the university’s senior theologian.

This closing of ranks in the Dominican order was also highly significant. It reinforced the already evident tribal element of the conflict, Dominicans against Augustinians, Wittenberg University against Leipzig and now Frankfurt. From this point on the Dominicans became identified as Luther’s most determined pursuers, and they crop up with increasing frequency in the judgment of his case. To Martin Luther’s baleful Augustinian eye they seemed to be particularly well entrenched in Rome. In the short run this perception may even have helped Luther. From the time that the Dominican chapter wrapped Tetzel in its protective embrace, Luther’s Augustinian brethren were inclined to give him the benefit of the doubt. This gave him crucial breathing space to make his case. This was important, because Luther was about to do something that would make many of his fellow churchmen distinctly uneasy.

Luther had decided that Tetzel’s theses required a reply. But he would make it not in Latin, the language of scholarly debate, but in German.

First, however, came an episode that would cause Luther considerable embarrassment. Tetzel’s countertheses were brought to Wittenberg from Halle, with instructions that they should be distributed among the students. But before this could be achieved the bookseller found himself surrounded by a hostile crowd. The whole consignment of broadsheets, apparently eight hundred copies, was taken from him and burned.

61

Although the desire to defend their own professor against a rival university played its part, this was not something that could be dismissed as a student prank. The repercussions were potentially profound; for Luther it was the first sign that his protest would raise forces he could not control and take the movement in directions he would not approve. Luther was forced to assure his friend Lang that he had had nothing to do with it; his turn burning books would come in 1520.

62

These riotous Wittenberg students do, however, remind us that in the violent and destructive culture wars set off by the Reformation, it was the evangelicals who were the first to commit their opponents’ works to the fire.

Tetzel’s stout defense of indulgences prompted a major change of direction in Luther. Previously he had been highly skeptical about taking theological debate outside the academy. Now he decided to embrace the wider public whose interests and loyalties had become increasingly engaged by the dramatic conflict unfolding around them. Luther would make a public defense of his theses on indulgences: in print, as Tetzel had responded to him in print, but now in the vernacular.

This was a signal moment for Martin Luther, and indeed for the Reformation. Up to this point Luther could plausibly have drawn back and laid the controversy on indulgences to rest; he could argue that he had merely proposed theses for debate, provocative and speculative, as the genre demanded. He could have acknowledged that some of his propositions had been imprudently expressed. His opponents could in turn accept that he had raised issues of importance. The carefully measured provisional response of the Mainz theologians seemed to point the way

to just such a resolution. The closing of ranks around Tetzel, denying any validity in Luther’s criticisms, had raised the stakes dramatically. If this was to be a public scandal, Luther would address the public. But by doing so, taking the debate out of the academic theater and the formal process of the dissertation, he also abandoned the protection of his status as a professor. From this point on Luther would be a marked man.

Luther began working on his German treatise early in March 1518; it was published toward the end of the month. The

Sermon on Indulgence and Grace

offered a succinct and trenchant defense of his teaching. But, as was always the way with Luther, he also moved the debate forward. For the first time, in the introductory contextual propositions, Luther questioned the traditional teaching on penance, which he here associated with the proponents of Scholastic theology. But it is also noteworthy that in addressing a lay audience Luther significantly reins back his criticism of the church hierarchy. The St. Peter’s indulgence is specifically mentioned—in the circumstances it could hardly be ignored—but the tract largely avoids the technical questions of authority raised in the ninety-five theses. Instead it is addressed directly to the lay Christian faced with practical dilemmas of salvation and the temptations of indulgences. The reader is given precise, practical guidance in short pithy sentences: It is a grievous error for anyone to think that he can make satisfaction for his own sins (thirteenth proposition). Indulgence helps no one improve but tolerates people’s imperfection (fourteenth). It is much better to benefit someone in need with a good work than to give to a building (sixteenth).

63

In itself the

Sermon on Indulgence and Grace

would not be a major contribution to the ongoing theological debate, or the emerging clash of authority. But it was an instant publishing sensation. Rhau-Grunenberg published two or possibly three editions; by the end of the year it had been reprinted in Leipzig four times, and twice each in Nuremberg, Augsburg, and Basel.

64

This set a pattern that would be followed for almost all of Luther’s vernacular works for the following years of controversy: an instant, insistent demand for the Wittenberg originals, followed

by immediate republication in the major citadels of German print. In this way Luther swiftly made his way into the homes of thousands of his fellow citizens, who had probably never before owned the work of a living German author. The decision to address a wider public had been his own; but it was print that had made him a national figure.

The

Sermon on Indulgence and Grace

alerted the German printing industry to Luther’s potential value. But what is perhaps most remarkable about this modest, unassuming work is what it reveals about Luther’s completely unexpected facility as a vernacular writer. This was his first serious foray into vernacular writing, yet it can only be described as a work of intuitive genius. Luther replaces the ninety-five propositions of the Latin theses with twenty short paragraphs, each developing a single aspect of the question. None is more than three or four sentences long; the sentences are short and direct. The whole work is a mere fifteen hundred words. It fits perfectly into an eight-page pamphlet.

This was a revolution in theological writing. For this was not an age that in general valued brevity, as the 95 theses of Luther and 106 of Tetzel made clear. Luther’s colleague Andreas von Karlstadt, ever a man of extremes, even contrived 406 theses on one occasion.

65

Nor was it any different with the spoken word. Luther’s choice of “Sermon” in the title almost seems to mock the genre, for as any attendee would attest, sermons were usually of interminable length. The sermon was a theatrical event, with repetition, exhortation, and rhetorical virtuosity, an endurance test for preacher and audience alike. In an age of strenuous devotion, this was rather the point. Luther, in contrast, had produced a sermon that could be read, or read aloud, in ten minutes, and still engaged the heart of the question.

With the German sermon, Luther had truly burned his boats. This was no longer a matter that could be resolved among academic theologians, but would now be played out in a public theater. One of the first to realize this was Johann Tetzel. As his ecclesiastical superiors grappled with the issue of how, and by whom, Luther would be brought to book, Tetzel took up his pen: and he, too, would write in the vernacular.

His

Rebuttal Against a Presumptuous Sermon of Twenty Erroneous Articles

is courteous and persistent, avoiding any of the personal vituperation that would characterize future exchanges between Luther and his Catholic opponents.

66

Tetzel also became the first of Luther’s opponents to make a connection between the criticism of indulgences and the heresies of John Wyclif and Jan Hus, a parentage that at this point Luther would have found acutely embarrassing. Tetzel’s work, published in a neat Leipzig edition, deserves to be better known, not least because it demonstrated that Luther’s opponents could, if they chose, compete very effectively in such a vernacular exchange.

67

Mostly, of course, they chose not to, a tactical error that left the field largely open for Luther’s supporters.