The Origins of AIDS (19 page)

Read The Origins of AIDS Online

Authors: Pepin

From segregation to cure

Quinimax

And the rest

An accident of history

From tropical diseases to blood-borne viruses

Leprosy is a disease of skin and nerves caused by

Mycobacterium leprae

, a bacterium which reproduces extremely slowly (one division every twelve days, instead of every half-hour for many other bacteria), hence its sluggish progression. Apart from the all too evident disfiguring lesions of the face (and elsewhere), known since biblical times, leprosy alters sensory perception, which in turn leads to auto-amputation of the extremities. For a long time, many leprosy patients did not receive any pharmacological treatment and were segregated into leprosaria, euphemistically called ‘agricultural colonies’ in French Africa

.

Mycobacterium leprae

, a bacterium which reproduces extremely slowly (one division every twelve days, instead of every half-hour for many other bacteria), hence its sluggish progression. Apart from the all too evident disfiguring lesions of the face (and elsewhere), known since biblical times, leprosy alters sensory perception, which in turn leads to auto-amputation of the extremities. For a long time, many leprosy patients did not receive any pharmacological treatment and were segregated into leprosaria, euphemistically called ‘agricultural colonies’ in French Africa

.

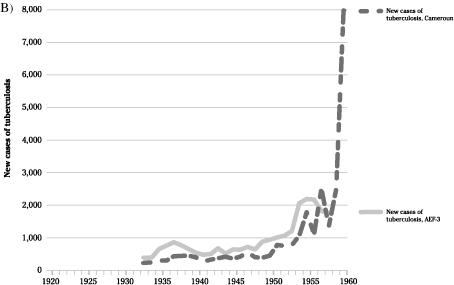

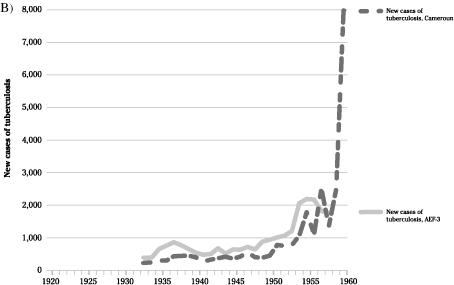

Figure 13

summarises the numbers of leprosy patients who did receive treatment. They were far fewer than cases of yaws or syphilis, but would ultimately receive the highest number of injections. Treatments were administered over several years, so these figures are a combination of new incident cases and prevalent cases diagnosed in the previous years. In Cameroun, from the late 1930s, a serious therapeutic effort was made. In AEF-3, which had fewer human and financial resources, the policy was not to bother with leprosy until modern therapeutic agents were introduced in the early 1950s. The extraordinary number of patients then treated included the cases that had been accumulating for decades because the disease was not lethal.

summarises the numbers of leprosy patients who did receive treatment. They were far fewer than cases of yaws or syphilis, but would ultimately receive the highest number of injections. Treatments were administered over several years, so these figures are a combination of new incident cases and prevalent cases diagnosed in the previous years. In Cameroun, from the late 1930s, a serious therapeutic effort was made. In AEF-3, which had fewer human and financial resources, the policy was not to bother with leprosy until modern therapeutic agents were introduced in the early 1950s. The extraordinary number of patients then treated included the cases that had been accumulating for decades because the disease was not lethal.

Initially, extracts of chaulmoogra, an Indian medicinal plant, were the main agents, given mostly IM (two to three times a week for the first year, then weekly for several years) but also orally, rectally, IV or directly in the lesions. Chaulmoogra was provided as bulk oil locally diluted or as vials. From the early 1930s to the late 1940s, following

enthusiastic reports by a

renowned

Saigon dermatologist, many lepers in Cameroun received IV methylene blue (a dye, resulting in greenish urine) concomitantly with IM chaulmoogra. The intended regimen of thirty to sixty IV injections over one year was often stopped prematurely due to

adverse effects. Another medicinal product, aqueous

Caloncoba

, was given IV as an adjuvant to chaulmoogra. In 1939, 20% of Cameroonian lepers received chaulmoogra monotherapy, 24%

Caloncoba

monotherapy, 13% methylene blue monotherapy while others received various combinations of these. This wide variety of regimens indicated that none had a clear-cut beneficial effect

.

Caloncoba

and methylene blue progressively lost favour

.

38

–

39

enthusiastic reports by a

renowned

Saigon dermatologist, many lepers in Cameroun received IV methylene blue (a dye, resulting in greenish urine) concomitantly with IM chaulmoogra. The intended regimen of thirty to sixty IV injections over one year was often stopped prematurely due to

adverse effects. Another medicinal product, aqueous

Caloncoba

, was given IV as an adjuvant to chaulmoogra. In 1939, 20% of Cameroonian lepers received chaulmoogra monotherapy, 24%

Caloncoba

monotherapy, 13% methylene blue monotherapy while others received various combinations of these. This wide variety of regimens indicated that none had a clear-cut beneficial effect

.

Caloncoba

and methylene blue progressively lost favour

.

38

–

39

A new class of antimicrobial drugs, the sulphones, was introduced in the 1950s and proved dramatically superior. At last there was an effective treatment. Non-compliant patients received a depot sulphone solution, administered fortnightly by visiting nurses to patients queuing by the side of the road, while those thought to be more reliable were given an oral sulphone which they took every day at home. By 1957, all Cameroonian lepers received sulphones, 80% orally and 20% IM. In AEF-3, the proportion treated with IM sulphones varied from 15% in Oubangui-Chari to 60% in

Moyen-Congo. These treatments were continued for a few years in patients with less severe leprosy and longer in cases of lepromatous leprosy where the bacterial load in infected tissues is higher

.

41

Moyen-Congo. These treatments were continued for a few years in patients with less severe leprosy and longer in cases of lepromatous leprosy where the bacterial load in infected tissues is higher

.

41

The other extremely common tropical disease for which injectable drugs were used on a large scale was malaria. Malaria can be caused by five different species of the

Plasmodium

parasites.

Plasmodium falciparum

is the most important by far, the one that kills. It causes fever with other non-specific symptoms such as muscle aches. In the severe form, the parasites destroy a large number of red blood cells (necessitating a transfusion), or lead to the occlusion of small blood vessels within the brain (the patient becomes comatose). In highly endemic areas of Africa, children develop some immunity against the parasite so that the severe forms are rarely seen above five years of age.

Plasmodium

parasites.

Plasmodium falciparum

is the most important by far, the one that kills. It causes fever with other non-specific symptoms such as muscle aches. In the severe form, the parasites destroy a large number of red blood cells (necessitating a transfusion), or lead to the occlusion of small blood vessels within the brain (the patient becomes comatose). In highly endemic areas of Africa, children develop some immunity against the parasite so that the severe forms are rarely seen above five years of age.

Cases of leprosy under treatment, and new cases of tuberculosis diagnosed in Cameroun Français and AEF-3.

Adapted from Pepin.

10

10

This disease received little attention in the annual reports of the colonial health systems because it was not a specific target of disease control interventions. Malaria was so common that its control was seen as being beyond the reach of even the most enthusiastic health planners. Counting cases was pointless in countries where half of the children carried a small number of malaria parasites in their blood year round. Furthermore, malaria was fatal almost exclusively among children, and

the authorities were interested mainly in short-term investments in the health of adults who paid taxes, produced cash crops and could be conscripted into the colonial army.

the authorities were interested mainly in short-term investments in the health of adults who paid taxes, produced cash crops and could be conscripted into the colonial army.

Thus the treatment of malaria was left to the discretion of each hospital and health centre, and no statistics were tabulated. It is hard to estimate the proportion of cases treated parenterally, but various preparations of quinine were available. In francophone Africa, for a long time the most popular product was called Quinimax. Parenteral quinine was generally administered IV rather than IM because the latter route caused abscesses or even gangrene at the injection site. Quinine tablets were available, and the injectable forms were given mostly to patients when a rapid effect was deemed necessary (cerebral malaria, severe anaemia), or to those presenting with nausea or vomiting who would not tolerate oral administration. Injections became very popular among the Africans, who thought this route had to be more powerful than any oral medication, so that in practice the indications for the parenteral treatment of malaria were broader than those mentioned in the textbooks. Another antimalarial drug,

quinacrine, could also be administered SC, IM or IV. Its use increased during WWII, when allied countries were cut off from their Asian sources of quinine.

Chloroquine, which first appeared after the war, was almost always given orally

.

37

–

39

quinacrine, could also be administered SC, IM or IV. Its use increased during WWII, when allied countries were cut off from their Asian sources of quinine.

Chloroquine, which first appeared after the war, was almost always given orally

.

37

–

39

In the 1930s and 1940s, only 1,000 cases of schistosomiasis were reported annually in Cameroun, and around 2,000 in AEF-3. Most patients were left untreated as the adverse effects of IM

antimonials or IV

emetine seemed worse than the symptoms of the infection. Clearly, the control of schistosomiasis did not play in central Africa the same role as in Egypt in the dissemination of blood-borne viruses

.

42

antimonials or IV

emetine seemed worse than the symptoms of the infection. Clearly, the control of schistosomiasis did not play in central Africa the same role as in Egypt in the dissemination of blood-borne viruses

.

42

No parenteral drug was used against filariasis, another group of tropical diseases. Most cases corresponded to

Loa loa

or

Mansonella perstans

found incidentally creeping in the blood during examinations for malaria or trypanosomiasis. These infections brought about little symptoms and were left untreated. River blindness was uncommon in central Africa, in contrast with its disastrous impact in West Africa. The only short-lived attempt for its mass treatment with IV

suramin took place in the Mayo

Kebbi district of

Tchad, which is outside our region of

interest. This strategy was quickly abandoned because of the severe adverse effects induced by the destruction of the parasite.

Loa loa

or

Mansonella perstans

found incidentally creeping in the blood during examinations for malaria or trypanosomiasis. These infections brought about little symptoms and were left untreated. River blindness was uncommon in central Africa, in contrast with its disastrous impact in West Africa. The only short-lived attempt for its mass treatment with IV

suramin took place in the Mayo

Kebbi district of

Tchad, which is outside our region of

interest. This strategy was quickly abandoned because of the severe adverse effects induced by the destruction of the parasite.

Tuberculosis was remarkably uncommon until 1950, with fewer than 500 cases annually in Cameroun and less than 1,000 in AEF-3 (

Figure 13

). No treatment was offered and there was no attempt to segregate patients in sanatoria. Later, incidence increased dramatically, coinciding with the introduction of chemotherapy. Most patients received IM streptomycin daily for the first month, then two to three times per week for eighteen to twenty-four months, along with oral drugs. In Cameroun, annual

streptomycin consumption increased from 100 (1949) to 511,941 grams (1959). The huge rise in incidence is troubling, and one wonders whether this may to some extent have reflected the early emergence of HIV-1, which substantially enhances the risk of developing tuberculosis. However, the introduction of effective treatments may have increased the number of patients seeking a diagnosis, the supply of diagnostic tests or the aggressiveness of

case-finding activities, as will be reviewed in the

next chapter

for the Belgian Congo

.

43

Figure 13

). No treatment was offered and there was no attempt to segregate patients in sanatoria. Later, incidence increased dramatically, coinciding with the introduction of chemotherapy. Most patients received IM streptomycin daily for the first month, then two to three times per week for eighteen to twenty-four months, along with oral drugs. In Cameroun, annual

streptomycin consumption increased from 100 (1949) to 511,941 grams (1959). The huge rise in incidence is troubling, and one wonders whether this may to some extent have reflected the early emergence of HIV-1, which substantially enhances the risk of developing tuberculosis. However, the introduction of effective treatments may have increased the number of patients seeking a diagnosis, the supply of diagnostic tests or the aggressiveness of

case-finding activities, as will be reviewed in the

next chapter

for the Belgian Congo

.

43

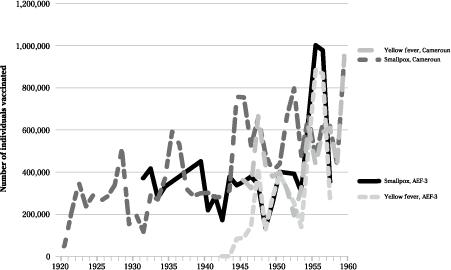

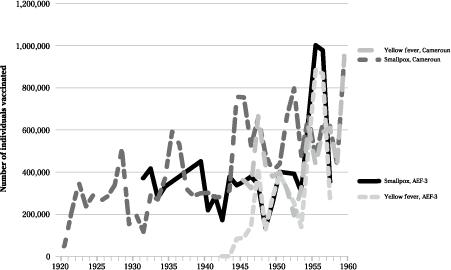

Vaccines administered on a large scale were those against smallpox (since the early 1920s) and yellow

fever (mid-1940s). The latter was a ‘scratch vaccine’ administered ID, simultaneously with the former. The policy was to re-immunise everyone every four to six years. Year-to-year variations (

Figure 14

) depended on vaccine availability, perceived threats and opportunities for immunisation by mobile teams. Other vaccines of unproven efficacy were given selectively and are unlikely to have played a part in the spread of blood-borne viruses

.

44

fever (mid-1940s). The latter was a ‘scratch vaccine’ administered ID, simultaneously with the former. The policy was to re-immunise everyone every four to six years. Year-to-year variations (

Figure 14

) depended on vaccine availability, perceived threats and opportunities for immunisation by mobile teams. Other vaccines of unproven efficacy were given selectively and are unlikely to have played a part in the spread of blood-borne viruses

.

44

Spain owned a tiny colony in central Africa, Guinea Espanola (now Guinea Ecuatorial), which is also inhabited by the

P.t.

troglodytes

. It consisted of a continental part,

Rio Muni, squeezed between Gabon and Cameroun, and the Atlantic islands of Fernando

Poo (now

Bioko) and

Annabon (the islands were part of a deal between Spain and

Portugal, exchanged for the

Sacramento colony in South America in the late eighteenth century). Reports of the health system suggest that the epidemiological situation of this small population was similar to that of Gabon and Cameroun, as were the health interventions. During the 1940s and 1950s, incidence rates of

yaws varied between 37 and 50 per 1,000,

syphilis between 3 and 4 per 1,000, and

trypanosomiasis

between 0.3 and 2.1 per 1,000. Pentamidinisation was used in some areas. It is thus possible that blood-borne viruses were transmitted in Guinea Espanola as well

.

45

–

48

P.t.

troglodytes

. It consisted of a continental part,

Rio Muni, squeezed between Gabon and Cameroun, and the Atlantic islands of Fernando

Poo (now

Bioko) and

Annabon (the islands were part of a deal between Spain and

Portugal, exchanged for the

Sacramento colony in South America in the late eighteenth century). Reports of the health system suggest that the epidemiological situation of this small population was similar to that of Gabon and Cameroun, as were the health interventions. During the 1940s and 1950s, incidence rates of

yaws varied between 37 and 50 per 1,000,

syphilis between 3 and 4 per 1,000, and

trypanosomiasis

between 0.3 and 2.1 per 1,000. Pentamidinisation was used in some areas. It is thus possible that blood-borne viruses were transmitted in Guinea Espanola as well

.

45

–

48

So the opportunities for the parenteral transmission of viruses throughout central Africa were numerous. Now we will try to understand how more than 40% of the elderly population of southern Cameroon got infected with

HCV, as a model for the putative parenteral transmission of HIV-1. Given that HCV is transmitted more efficiently through IV rather than other types of injections, for any given patient the highest risk must have been for sleeping sickness cases treated with IV

tryparsamide (around

thirty-six injections) or

leprosy patients given IV

methylene blue or

Caloncoba

plus IM

chaulmoogra over a period of years, followed by patients who received just a few IV injections, for instance to treat malaria, then those who received the biannual pentamidine IM injections and finally, at the other end of the spectrum, individuals given only intradermal immunisations every five years.

49

HCV, as a model for the putative parenteral transmission of HIV-1. Given that HCV is transmitted more efficiently through IV rather than other types of injections, for any given patient the highest risk must have been for sleeping sickness cases treated with IV

tryparsamide (around

thirty-six injections) or

leprosy patients given IV

methylene blue or

Caloncoba

plus IM

chaulmoogra over a period of years, followed by patients who received just a few IV injections, for instance to treat malaria, then those who received the biannual pentamidine IM injections and finally, at the other end of the spectrum, individuals given only intradermal immunisations every five years.

49

Figure 14

Number of individuals vaccinated against smallpox and yellow fever in Cameroun Français and AEF-3.

Number of individuals vaccinated against smallpox and yellow fever in Cameroun Français and AEF-3.

Adapted from Pepin.

10

10

Other books

The Paper Magician by Charlie N. Holmberg

The Righteous Men (2006) by Sam Bourne

Basketball (or Something Like It) by Nora Raleigh Baskin

Touched By Midas (SEALs Going Hot Book 4) by Brenna Zinn

Betrayed by Love by Lee, Marilyn

The Real Doctor Will See You Shortly by Matt McCarthy

Writ on Water by Melanie Jackson

I'm with You by Maynard, Glenna

Circus of Thieves and the Raffle of Doom by William Sutcliffe

The Wolf in the Attic by Paul Kearney