The Origins of AIDS (22 page)

Read The Origins of AIDS Online

Authors: Pepin

An epidemic of tuberculosis

Taking good care of free women

In Africa, tuberculosis is by far the most common ‘opportunistic’ infection among HIV-infected patients. Without HIV, the natural course of infection with

Mycobacterium tuberculosis

is as follows: when the bacillus is inhaled, this generally causes transient and non-specific symptoms, then the pathogen becomes dormant (no replication) somewhere in the lungs, and the patient feels fine until the bacteria are reactivated months or years later. Of 100 persons infected with the pathogen, only 10 will develop tuberculosis in their lifetime while in the other 90 the bacillus will remain dormant in their lungs forever, until they die of something else. The HIV-induced immunosuppression leads to much more frequent reactivation of the dormant infection: from 10% throughout life, the risk becomes 10% each year. In central Africa, where about 5% of the adult population is HIV-infected, 50% of patients with tuberculosis carry the virus.

Mycobacterium tuberculosis

is as follows: when the bacillus is inhaled, this generally causes transient and non-specific symptoms, then the pathogen becomes dormant (no replication) somewhere in the lungs, and the patient feels fine until the bacteria are reactivated months or years later. Of 100 persons infected with the pathogen, only 10 will develop tuberculosis in their lifetime while in the other 90 the bacillus will remain dormant in their lungs forever, until they die of something else. The HIV-induced immunosuppression leads to much more frequent reactivation of the dormant infection: from 10% throughout life, the risk becomes 10% each year. In central Africa, where about 5% of the adult population is HIV-infected, 50% of patients with tuberculosis carry the virus.

From the mid-1930s there was a slow but relentless progression in the number of cases of tuberculosis reported, and then a dramatic rise in the 1950s (

Figure 15

). Is it possible that, in retrospect, this phenomenon reflected the spread of HIV which was already triggering many more cases of reactivation of the tuberculous bacillus? Well, perhaps, but there are several alternative explanations for this increasing incidence. First, medical historians and clinicians of the time agree that the agent of tuberculosis was introduced into central Africa by the Europeans.

Very much like HIV, the urbanisation and the development of communication networks facilitated its spread, further enhanced by the promiscuity of urban residents who often had to share a bedroom with several other people. As in many cases where there is a decades-long interval between infection and ultimately developing the disease, more intense transmission in the 1920s would have led to a higher incidence twenty, thirty or forty years down the line. Second, there was a determined drive to develop the health system after WWII, so that ever larger numbers of Congolese had access to a healthcare institution where it was possible to diagnose tuberculosis. Third, the availability of effective drugs starting in the early 1950s made it more attractive for healthcare providers to diagnose tuberculosis: something could be done about it. Fourth, this treatment availability led during the 1950s to the widespread use in urban areas of radiographic surveys aimed at actively detecting cases of tuberculosis.

For instance in 1957, the

Centre de Dépistage de la Tuberculose in Léopoldville performed 44,234 chest x-rays to look for signs of tuberculosis. X-rays were performed on contacts of cases (all persons living on the same compound), on individuals who looked unwell during the annual medical census and in some parts of town on the whole population.

Such aggressive case-finding increased three-fold the number of cases detected

.

25

,

46

,

47

Figure 15

). Is it possible that, in retrospect, this phenomenon reflected the spread of HIV which was already triggering many more cases of reactivation of the tuberculous bacillus? Well, perhaps, but there are several alternative explanations for this increasing incidence. First, medical historians and clinicians of the time agree that the agent of tuberculosis was introduced into central Africa by the Europeans.

Very much like HIV, the urbanisation and the development of communication networks facilitated its spread, further enhanced by the promiscuity of urban residents who often had to share a bedroom with several other people. As in many cases where there is a decades-long interval between infection and ultimately developing the disease, more intense transmission in the 1920s would have led to a higher incidence twenty, thirty or forty years down the line. Second, there was a determined drive to develop the health system after WWII, so that ever larger numbers of Congolese had access to a healthcare institution where it was possible to diagnose tuberculosis. Third, the availability of effective drugs starting in the early 1950s made it more attractive for healthcare providers to diagnose tuberculosis: something could be done about it. Fourth, this treatment availability led during the 1950s to the widespread use in urban areas of radiographic surveys aimed at actively detecting cases of tuberculosis.

For instance in 1957, the

Centre de Dépistage de la Tuberculose in Léopoldville performed 44,234 chest x-rays to look for signs of tuberculosis. X-rays were performed on contacts of cases (all persons living on the same compound), on individuals who looked unwell during the annual medical census and in some parts of town on the whole population.

Such aggressive case-finding increased three-fold the number of cases detected

.

25

,

46

,

47

We will now examine how a well-intentioned initiative by a non-profit organisation may have contributed to the early spread of HIV-1 in the Congo’s capital. An early version of the Croix-Rouge du Congo (CRC) established the first hospitals around 1890 in

Boma and Léopoldville, but it was disbanded with the cession of the EIC to Belgium. In 1926, the

Belgian Red Cross established a new CRC. Money was raised in Belgium, but also from businesses in the colony. Early on, it was decided

that the CRC would focus its efforts on the Province Orientale, and on Léopoldville where two STD clinics were opened with the help of the Belgian National League against the Venereal Threat.

48

Boma and Léopoldville, but it was disbanded with the cession of the EIC to Belgium. In 1926, the

Belgian Red Cross established a new CRC. Money was raised in Belgium, but also from businesses in the colony. Early on, it was decided

that the CRC would focus its efforts on the Province Orientale, and on Léopoldville where two STD clinics were opened with the help of the Belgian National League against the Venereal Threat.

48

During WWII, the CRC provided support for Belgian families from donations made by colonials still in the Congo. It dispatched correspondence between the Congo and occupied Belgium, sent food and clothes to Belgian war prisoners and funded a home for children of colonial officers who had been caught up in Belgium by the war, away from their parents. However, generosity always has limits, and in this case

mulattoes were excluded from the list of children to be supported

.

mulattoes were excluded from the list of children to be supported

.

In 1947, the CRC brought to the Congo the country’s first paediatrician, Claude Lambotte, along with his wife Jeanne Legrand, also medically qualified. They convinced the CRC to build a 100-bed paediatric hospital, which was inaugurated in 1953. Unfortunately, this facility proved very expensive to operate, which threatened the very survival of the CRC. As the city’s endless expansion created a need for more STD clinics, the charity decided rather to withdraw completely from this field and handed over its two clinics to the government. It had also become uncomfortable with the coercive nature of the STD clinics. Reluctant patients being forcibly brought in by the police was inconsistent with the values of the international Red Cross movement.

In 1957, the Croix-Rouge opened a blood transfusion centre in Léo, with a pool of volunteer donors, which was certainly more in line with its traditional responsibilities. Until then, blood had to be given by relatives or friends of the recipient and was transfused within minutes of collection. One of the CRC board members in Belgium, Professor Albert

Dubois, warned that strict measures would need to be taken to avoid transmitting diseases such as malaria, trypanosomiasis and viruses during transfusions. ‘Don’t worry,’ he was told, ‘our medical officers in Léo will take care of that.’ Legrand became the first director of the transfusion centre, but she was caught up in a series of conflicts with doctors at the main hospital (who accused her of stealing their own blood donors), with the volunteer directors of the Léopoldville branch of the CRC, and others. In those days, women working as professionals did not have an easy time. She was fired by the CRC, went into a depression and died in Léo in 1960, with a request to be buried alongside the Africans

. It is unlikely that this

blood bank contributed to the early dissemination of HIV in Léo because the prevalence among donors must have been rather low and many of the recipients were

young children who, had they acquired HIV, would have died before reaching sexual maturity. A year after independence, the Brussels-based CRC disbanded and the blood bank was transferred to other institutions

.

49

Dubois, warned that strict measures would need to be taken to avoid transmitting diseases such as malaria, trypanosomiasis and viruses during transfusions. ‘Don’t worry,’ he was told, ‘our medical officers in Léo will take care of that.’ Legrand became the first director of the transfusion centre, but she was caught up in a series of conflicts with doctors at the main hospital (who accused her of stealing their own blood donors), with the volunteer directors of the Léopoldville branch of the CRC, and others. In those days, women working as professionals did not have an easy time. She was fired by the CRC, went into a depression and died in Léo in 1960, with a request to be buried alongside the Africans

. It is unlikely that this

blood bank contributed to the early dissemination of HIV in Léo because the prevalence among donors must have been rather low and many of the recipients were

young children who, had they acquired HIV, would have died before reaching sexual maturity. A year after independence, the Brussels-based CRC disbanded and the blood bank was transferred to other institutions

.

49

However, a specialised institution which warrants greater attention is the Dispensaire Antivénérien (STD clinic). It may have played a crucial role in the iatrogenic transmission of HIV-1 in Léopoldville because it was the main provider of care for free women, all of whom had to show up for the regular examinations necessary for their health card to be stamped. In 1929, the CRC opened a STD clinic in Léo-Est (

Barumbu district). Like many such clinics, its official name was later changed to the more innocuous

Centre de Médecine Sociale (patients preferred being seen by relatives and neighbours going to a social medicine centre than a venereal disease clinic). Eventually, a smaller satellite clinic was opened in Léo-Ouest. While the annual reports of the CRC provided nice photographs of its leprosarium and hospital in Province Orientale and its paediatric facilities in Léopoldville, the charity was more discreet about its STD clinics.

50

,

51

Barumbu district). Like many such clinics, its official name was later changed to the more innocuous

Centre de Médecine Sociale (patients preferred being seen by relatives and neighbours going to a social medicine centre than a venereal disease clinic). Eventually, a smaller satellite clinic was opened in Léo-Ouest. While the annual reports of the CRC provided nice photographs of its leprosarium and hospital in Province Orientale and its paediatric facilities in Léopoldville, the charity was more discreet about its STD clinics.

50

,

51

The STD clinics provided free care to women or men who presented spontaneously with a genital complaint (generally a discharge or ulcer) and whose employers did not provide medical care. For men, these would be recent arrivals, the few who were unemployed and all those working for small enterprises or for individuals (domestic staff). As very few women worked in the formal sector, for them the Dispensaire Antivénérien was the only accessible institution. In practice, most free women of Léopoldville, fiscally defined as financially independent adult women not living with a husband, attended at least a few times per year. Contact tracing also generated part of the caseload. Males presenting with an STD had to refer their recent sexual contact(s), otherwise a visiting nurse would come to their compound for this purpose, potentially causing embarrassment.

Furthermore, male migrants to Léopoldville had to show up at the same clinics upon arrival in order to comply with health regulations and obtain their

permis de séjour

(they were also required to attend the

tuberculosis centre nearby).

Furthermore, male migrants to Léopoldville had to show up at the same clinics upon arrival in order to comply with health regulations and obtain their

permis de séjour

(they were also required to attend the

tuberculosis centre nearby).

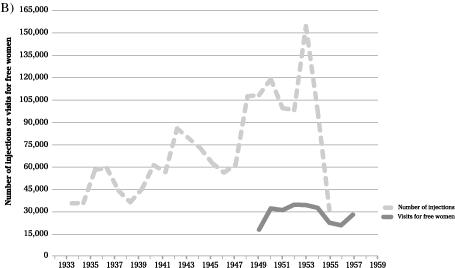

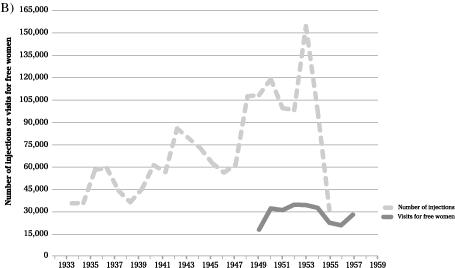

The statistics presented in

Figure 18

tabulate the totals for the two clinics together, but in practice the Léo-Ouest clinic never got off the ground and 95% of the total number of cases and number of injections correspond to the work done in Léo-Est. The bulk of the caseload

consisted of thousands of asymptomatic free women who came for screening because they were required to do so by law, in theory every month. At its peak, 32,000 such visits took place each year.

Figure 18

tabulate the totals for the two clinics together, but in practice the Léo-Ouest clinic never got off the ground and 95% of the total number of cases and number of injections correspond to the work done in Léo-Est. The bulk of the caseload

consisted of thousands of asymptomatic free women who came for screening because they were required to do so by law, in theory every month. At its peak, 32,000 such visits took place each year.

Number of new cases of gonorrhoea and syphilis, injections of various drugs and number of visits for free women at the Dispensaires Antivénériens of Léopoldville.

Data on the incidence of new cases of syphilis or gonorrhoea, the number of women and men seen at least once during the year, the number of serological assays for syphilis and the number of injections administered were provided in the annual reports of the Croix-Rouge du Congo, as well as in health service reports.

The number of new cases of syphilis or gonorrhoea diagnosed each year varied substantially, reflecting the expansion of the capital’s population and changes not just in diagnostic strategies but also in the efforts made to screen free women.

47

,

51

The number of new cases of syphilis or gonorrhoea diagnosed each year varied substantially, reflecting the expansion of the capital’s population and changes not just in diagnostic strategies but also in the efforts made to screen free women.

47

,

51

Given that those treated for syphilis or gonorrhoea had to attend repeatedly for prolonged courses of injectable drugs but also for a long follow-up, by the early 1950s, as the population of Léo had increased dramatically, up to 1,000 patients attended the Léo-Est Dispensaire Antivénérien each day. The medical officers estimated that they were providing more or less regular check-ups to 3,500 free women. The clinic, which held only four rooms, opened at 4.30 a.m. so men could receive their treatments before going to work. This extremely high turnover of patients made it impossible for syringes and needles to be sterilised properly. In 1952, the Léo-Est facility was enlarged: syphilitics on one side, those with gonorrhoea on the other. STD screening of migrants was abandoned as it was deemed to provide little in the way of results

. The blood samples were sent to the Institute of Tropical Medicine for testing. In 1954, 85,654 serological tests for syphilis were performed

.

. The blood samples were sent to the Institute of Tropical Medicine for testing. In 1954, 85,654 serological tests for syphilis were performed

.

In retrospect, it is extraordinary that the treatment received by most patients of the Dispensaire Antivénérien was useless: wrong diagnoses, ineffective drugs. The reports suggest that, in the late 1940s, the medical officers began to wonder whether these efforts were a waste of time. In the 1949–54 reports, tables show that, of 7,204 new diagnoses of syphilis, only 111, 97 and 29 patients had signs compatible with primary, secondary or tertiary syphilis respectively. All of the others, 97% of patients with so-called syphilis, were given IV or IM drugs merely because they had a positive serology.

Even today, the serological assays for syphilis do not discriminate between this latter infection and yaws, the non-venereal disease caused by a closely related bacterium. With both infections, the serological assays remain positive at a low titre for a very long period of time and even for life with some of the best assays. At the time, the medical thinking was that patients needed to be treated repeatedly with rather ineffective

drugs until their serology came back completely negative. In 1952, 22% of a random sample of 1,000 adults living in Léo had a positive serology for syphilis/yaws, compared to 34% of free women. Given the high incidence of yaws in the preceding decades in the rural areas where many of these individuals originated, most of these cases with a positive serology probably corresponded to a past episode of yaws, which the patient could not recall because it had occurred in childhood.

However, if that person was a free woman or male migrant and happened to be tested at the STD clinic, she/he was always considered to be syphilitic and received long courses of drugs containing arsenic or

bismuth

until penicillin was introduced around 1954. Even with this wonder drug, half of the patients remained seropositive for ‘syphilis’

.

51

Even today, the serological assays for syphilis do not discriminate between this latter infection and yaws, the non-venereal disease caused by a closely related bacterium. With both infections, the serological assays remain positive at a low titre for a very long period of time and even for life with some of the best assays. At the time, the medical thinking was that patients needed to be treated repeatedly with rather ineffective

drugs until their serology came back completely negative. In 1952, 22% of a random sample of 1,000 adults living in Léo had a positive serology for syphilis/yaws, compared to 34% of free women. Given the high incidence of yaws in the preceding decades in the rural areas where many of these individuals originated, most of these cases with a positive serology probably corresponded to a past episode of yaws, which the patient could not recall because it had occurred in childhood.

However, if that person was a free woman or male migrant and happened to be tested at the STD clinic, she/he was always considered to be syphilitic and received long courses of drugs containing arsenic or

bismuth

until penicillin was introduced around 1954. Even with this wonder drug, half of the patients remained seropositive for ‘syphilis’

.

51

The precision of the diagnoses among free women was no better for gonorrhoea. In men, diagnosing gonorrhoea (or

chlamydia) is straightforward: pus drips out of the penis. Among women, it is the opposite: most remain asymptomatic and less than 10% of those presenting with a vaginal discharge have gonorrhoea. The STD dispensaries could not cultivate the gonococcus, and did simple stains of the vaginal secretions. Such tests are not very good at identifying those infected as there are non-pathogenic bacteria within the normal vaginal flora that look the same as the gonococcus. Patients thought to have gonorrhoea were treated for up to two months with drugs that aimed to combat the infection by triggering a high fever. They received injections of milk(!), typhoid

vaccine(!), a product called Gono-yatren, etc. Starting in 1951, effective antibiotics such as penicillin, sulphonamides or

streptomycin were given but only at the end of this ‘preparatory’ course

.

chlamydia) is straightforward: pus drips out of the penis. Among women, it is the opposite: most remain asymptomatic and less than 10% of those presenting with a vaginal discharge have gonorrhoea. The STD dispensaries could not cultivate the gonococcus, and did simple stains of the vaginal secretions. Such tests are not very good at identifying those infected as there are non-pathogenic bacteria within the normal vaginal flora that look the same as the gonococcus. Patients thought to have gonorrhoea were treated for up to two months with drugs that aimed to combat the infection by triggering a high fever. They received injections of milk(!), typhoid

vaccine(!), a product called Gono-yatren, etc. Starting in 1951, effective antibiotics such as penicillin, sulphonamides or

streptomycin were given but only at the end of this ‘preparatory’ course

.

As a result of these debatable diagnostic and therapeutic approaches, during the 1930s and 1940s the STD clinics administered 50,000 injections per year on average (95% of these at the Léo-Est site). About 60% of these injections were given IV. In the 1950s, during the post-war demographic boom, the number of injections fluctuated around 100,000 per year, peaking at the extraordinary level of 154,572 by 1953. This number decreased rapidly thereafter as penicillin was introduced, a course of which required fewer injections than the arsenicals

.

.

It is generally difficult to gather information about the procedures used for the sterilisation of syringes and needles during the colonial era.

In this case, however, it is illuminating to read a paper about hepatitis in Léopoldville written in 1953 by

Dr Paul Beheyt, the internal medicine specialist at the

Hôpital des Congolais.

The author distinguishes epidemic hepatitis from inoculation hepatitis, the latter being defined as a patient developing hepatitis between 45 and 150 days after having received IV injections or transfusions. Inoculation hepatitis must have corresponded mostly to hepatitis B, because acute infection with

hepatitis C rarely causes a disease severe enough for the patient to develop jaundice. Of sixty-nine cases of inoculation hepatitis diagnosed during 1951–2, thirty-two had received IV arsenical drugs at the Léo-Est STD clinic, corresponding to 0.9% of the patients treated during the same period by this institution. This measure of risk was greatly underestimated because the reference hospital diagnosed only a fraction of all cases of inoculation hepatitis occurring in Léopoldville, and the iatrogenic infection could only occur among patients who had not been infected with HBV earlier in their lives, at most 5% of adults in central Africa

.

52

In this case, however, it is illuminating to read a paper about hepatitis in Léopoldville written in 1953 by

Dr Paul Beheyt, the internal medicine specialist at the

Hôpital des Congolais.

The author distinguishes epidemic hepatitis from inoculation hepatitis, the latter being defined as a patient developing hepatitis between 45 and 150 days after having received IV injections or transfusions. Inoculation hepatitis must have corresponded mostly to hepatitis B, because acute infection with

hepatitis C rarely causes a disease severe enough for the patient to develop jaundice. Of sixty-nine cases of inoculation hepatitis diagnosed during 1951–2, thirty-two had received IV arsenical drugs at the Léo-Est STD clinic, corresponding to 0.9% of the patients treated during the same period by this institution. This measure of risk was greatly underestimated because the reference hospital diagnosed only a fraction of all cases of inoculation hepatitis occurring in Léopoldville, and the iatrogenic infection could only occur among patients who had not been infected with HBV earlier in their lives, at most 5% of adults in central Africa

.

52

Other books

El Imperio Romano by Isaac Asimov

Blood Tears by JD Nixon

Fever by Sharon Butala

The Summer Day is Done by Mary Jane Staples

The Saint's Devilish Deal by Knight, Kristina

Lumbersexual (Novella) by Leslie McAdam

Grace be a Lady (Love & War in Johnson County Book 1) by Heather Blanton

Snatchers (Book 8): The Dead Don't Pray by Whittington, Shaun

Heat Wave by Arnold, Judith

Promise Not to Tell: A Novel by Jennifer McMahon