The Origins of AIDS (20 page)

Read The Origins of AIDS Online

Authors: Pepin

Indeed, in Africa,

Brazil and Asia, leprosy patients treated in the distant past are more likely than others to be infected not just with HCV but also with

HBV and the HTLV-1 retrovirus

.

However, the proportion of Cameroonians ever treated for trypanosomiasis or leprosy was lower than the 40–50% who became HCV-infected in some areas, implying that other interventions must have played a role as well.

50

–

54

Brazil and Asia, leprosy patients treated in the distant past are more likely than others to be infected not just with HCV but also with

HBV and the HTLV-1 retrovirus

.

However, the proportion of Cameroonians ever treated for trypanosomiasis or leprosy was lower than the 40–50% who became HCV-infected in some areas, implying that other interventions must have played a role as well.

50

–

54

In Cameroon, populations with a high HCV prevalence live in

Yaoundé or communities in the southern rain forest (

Figure 9

and

Map 5

). I initially believed that the HCV epidemic could have been driven by campaigns against yaws, for several reasons. First, the sheer numbers: from the mid-1930s till the late 1950s, in some regions, the whole population developed yaws within a few years and received antitreponemal drugs. Second, the age distribution: yaws was more common among children who had the opportunity to survive until the mid-1990s when HCV surveys were carried out. Third, the rise in incidence of yaws in Cameroun after 1935 corresponds chronologically to what can be inferred to be the period of highest HCV transmission. Fourth, the geographic distribution of HCV coincides with that of yaws, whose incidence was much higher in coastal and forested regions than in northern savannahs.

10

Yaoundé or communities in the southern rain forest (

Figure 9

and

Map 5

). I initially believed that the HCV epidemic could have been driven by campaigns against yaws, for several reasons. First, the sheer numbers: from the mid-1930s till the late 1950s, in some regions, the whole population developed yaws within a few years and received antitreponemal drugs. Second, the age distribution: yaws was more common among children who had the opportunity to survive until the mid-1990s when HCV surveys were carried out. Third, the rise in incidence of yaws in Cameroun after 1935 corresponds chronologically to what can be inferred to be the period of highest HCV transmission. Fourth, the geographic distribution of HCV coincides with that of yaws, whose incidence was much higher in coastal and forested regions than in northern savannahs.

10

The same north–south gradient in yaws incidence was observed in the AEF, now mirrored by a higher HCV prevalence in southern

areas. In these countries, HCV prevalence is three to six times lower in

Pygmies than

Bantus, perhaps reflecting less intensive uptake of medical interventions among the former. There is also a north–south gradient in HTLV-1 prevalence, suggesting that this retrovirus may have been transmitted iatrogenically during the same interventions

.

7

,

55

–

58

areas. In these countries, HCV prevalence is three to six times lower in

Pygmies than

Bantus, perhaps reflecting less intensive uptake of medical interventions among the former. There is also a north–south gradient in HTLV-1 prevalence, suggesting that this retrovirus may have been transmitted iatrogenically during the same interventions

.

7

,

55

–

58

But there was another common tropical disease with a marked north–south gradient in incidence: malaria. While malaria occurs throughout tropical Africa, its distribution is heterogeneous, in line with that of its vector, the female anopheline mosquito. The risk of malaria is quantified by the number of infective mosquito bites sustained each year by each person. In tropical Africa, the median number of infective bites is 77 per year, but in the rural and rainy areas of central Africa this number is generally ≥≥200. The record belongs to a village of Equatorial

Guinea, where humans sustain 1,030 infective bites per year, three per day! In large cities such as

Kinshasa and Brazzaville, the risk is lower (3–30 bites) because there is less stagnant water where the vectors can breed and many more humans in relation to the population of mosquitoes. But

one just has to drive fifteen kilometres to the semi-rural areas around Kinshasa and the risk goes up to 620 bites per year.

59

–

61

Guinea, where humans sustain 1,030 infective bites per year, three per day! In large cities such as

Kinshasa and Brazzaville, the risk is lower (3–30 bites) because there is less stagnant water where the vectors can breed and many more humans in relation to the population of mosquitoes. But

one just has to drive fifteen kilometres to the semi-rural areas around Kinshasa and the risk goes up to 620 bites per year.

59

–

61

In the southern and forested areas of Cameroon, there is up to 4,000 mm of rain each year, compared to only 800 mm in the extreme north. The number of infective bites varies accordingly, with high values in the south-west of the country, and low values in the arid north. The risk of developing malaria, and of eventually needing to receive IV

quinine, varies along the same patterns. Thus malaria also correlated nicely with HCV distribution: a marked north–south gradient, a high incidence so that a large proportion of the population would receive parenteral antimalarial drugs at least once, the correct age distribution (more severe in children) and the correct time frame (the frequency of its parenteral treatment presumably increased in parallel with the development of fixed health services, from the 1930s onward).

quinine, varies along the same patterns. Thus malaria also correlated nicely with HCV distribution: a marked north–south gradient, a high incidence so that a large proportion of the population would receive parenteral antimalarial drugs at least once, the correct age distribution (more severe in children) and the correct time frame (the frequency of its parenteral treatment presumably increased in parallel with the development of fixed health services, from the 1930s onward).

To determine which interventions had really driven HCV transmission in southern Cameroon, we conducted a survey in the city of

Ebolowa, among individuals aged sixty years or more, 56% of whom were HCV-infected, the highest prevalence in the world, while 74% had antitreponemal antibodies, indicating prior

yaws or syphilis. We found no evidence that HCV had been transmitted during yaws treatment; many cases occurred during childhood and those treated parenterally received IM rather than IV injections.

62

Ebolowa, among individuals aged sixty years or more, 56% of whom were HCV-infected, the highest prevalence in the world, while 74% had antitreponemal antibodies, indicating prior

yaws or syphilis. We found no evidence that HCV had been transmitted during yaws treatment; many cases occurred during childhood and those treated parenterally received IM rather than IV injections.

62

However, 80% of the interviewees had experienced at least once in their lifetime an episode of illness for which IV injections were administered, and in about two-thirds of the cases this was for the treatment of malaria. HCV infection was associated with such treatments against malaria and, in the men’s case, with having been circumcised traditionally (during collective ceremonies, using knives or broken bottles). Because of its high frequency, the IV treatment of malaria had been the main driver of the transmission of HCV

.

62

.

62

We conducted a similar study of elderly individuals in a rural area of south-west Central African Republic (in and around Nola) which used to be, in the 1930s and 1940s, the most virulent focus of African trypanosomiasis. HCV prevalence was much lower than in Cameroun but we found that having been treated for trypanosomiasis in the 1930s and 1940s was associated with HCV, while having received injections of

pentamidine for the prevention of trypanosomiasis (between 1946 and 1953) was associated with infection with the

HTLV-1 retrovirus. The latter, although much less studied as a blood-borne agent, is an

interesting proxy for HIV-1, because it also originated from

Pan troglodytes

and infects CD4 lymphocytes (without causing AIDS). We also documented an extraordinary excess mortality amongst individuals who had been treated for sleeping sickness in the 1930s and 1940s. After excluding all other causes, we concluded that this excess mortality was probably caused by the iatrogenic transmission of HIV-1

.

63

pentamidine for the prevention of trypanosomiasis (between 1946 and 1953) was associated with infection with the

HTLV-1 retrovirus. The latter, although much less studied as a blood-borne agent, is an

interesting proxy for HIV-1, because it also originated from

Pan troglodytes

and infects CD4 lymphocytes (without causing AIDS). We also documented an extraordinary excess mortality amongst individuals who had been treated for sleeping sickness in the 1930s and 1940s. After excluding all other causes, we concluded that this excess mortality was probably caused by the iatrogenic transmission of HIV-1

.

63

Thus several medical interventions were associated with the iatrogenic transmission of blood-borne viruses, and it seems likely that the respective contribution of each varied from place to place, and also over time, depending on the local epidemiology of tropical diseases. And if interventions for the control of tropical diseases contributed to the transmission of HCV and HTLV-1 in Cameroun and AEF in the middle of the twentieth century, the same procedures must have amplified HIV-1 as well, from a single hunter/cook occupationally infected with SIV

cpz

to several hundred patients treated with

arsenicals or other drugs, a threshold beyond which sexual transmission could prosper

.

cpz

to several hundred patients treated with

arsenicals or other drugs, a threshold beyond which sexual transmission could prosper

.

As reviewed in

Chapter 4

, the number of individuals occupationally infected with SIV

cpz

around 1921 was probably less than ten, but the probability that these individuals received IV or IM treatment for yaws, syphilis, trypanosomiasis, leprosy or malaria was very high, near 100% for those who lived in the areas hyperendemic for yaws and malaria. Once a second person had been iatrogenically infected with SIV

cpz

, he/she would develop a high viraemia during primary infection and for a few weeks would be extremely infectious for other patients treated in the same facility with the same hastily sterilised syringes and needles. A vicious circle could result.

Chapter 4

, the number of individuals occupationally infected with SIV

cpz

around 1921 was probably less than ten, but the probability that these individuals received IV or IM treatment for yaws, syphilis, trypanosomiasis, leprosy or malaria was very high, near 100% for those who lived in the areas hyperendemic for yaws and malaria. Once a second person had been iatrogenically infected with SIV

cpz

, he/she would develop a high viraemia during primary infection and for a few weeks would be extremely infectious for other patients treated in the same facility with the same hastily sterilised syringes and needles. A vicious circle could result.

In the

next chapter

, we will examine what happened at the same time in the Belgian Congo. It is unlikely that the original SIV

cpz

-infected cut hunter lived in this other colony, in which only a tiny fraction of the continent-wide populations of

P.t. troglodytes

were present. Furthermore, there is no evidence that the

bonobo, found only in the Belgian Congo, played a role in the emergence of HIV-1. However, the city of Léopoldville was at the heart of the early dissemination of the virus: this is the place where the two oldest HIV-1-containing specimens were discovered and the area with the highest genetic diversity of HIV-1 isolates in the world.

next chapter

, we will examine what happened at the same time in the Belgian Congo. It is unlikely that the original SIV

cpz

-infected cut hunter lived in this other colony, in which only a tiny fraction of the continent-wide populations of

P.t. troglodytes

were present. Furthermore, there is no evidence that the

bonobo, found only in the Belgian Congo, played a role in the emergence of HIV-1. However, the city of Léopoldville was at the heart of the early dissemination of the virus: this is the place where the two oldest HIV-1-containing specimens were discovered and the area with the highest genetic diversity of HIV-1 isolates in the world.

9

The legacies of colonial medicine II:

the Belgian Congo

The control of infectious diseases

The legacies of colonial medicine II:

the Belgian Congo

While France was busy running the health systems of more than twenty-five territories in Africa, around the Indian Ocean, in south-east Asia and the Americas, Belgium could concentrate its efforts on its three African colonies, the largest of which by far was the Belgian Congo. Belgium was justifiably proud of its achievements in the Congo, whose health system soon acquired the reputation of being the best in tropical Africa. This led to a substantial improvement in the health of the Congolese people, but also to numerous opportunities for the transmission of blood-borne microbial agents. What happened in and around Léopoldville will be especially relevant, as this is the area where ultimately HIV-1 spread and diversified.

For this part of the story, the best sources of information are in Belgium. Since 1960 the ministry of foreign affairs has kept the archives of the Belgian Congo, which are accessible to researchers. The Royal Library and the university libraries of Brussels, Louvain and Louvain-la-Neuve hold impressive collections of books and journals relating to the country’s former colonies. In

Antwerp, the tropical medicine institute has made available online the

Annales de la Société Belge de Médecine Tropicale

, in which Belgian medical officers working in the tropics used to publish their findings. More detailed articles were published through the Académie Royale des Sciences Coloniales.

Antwerp, the tropical medicine institute has made available online the

Annales de la Société Belge de Médecine Tropicale

, in which Belgian medical officers working in the tropics used to publish their findings. More detailed articles were published through the Académie Royale des Sciences Coloniales.

The work of colonial doctors in the Congo was summarised by

Jacques Schwetz, a Russian émigré who became a prolific tropical medicine researcher. For somebody to be considered a good doctor, two instruments were essential: a microscope, and a syringe for IV and SC injections. We will see that there were other similarities with the French colonies, but also a few interesting distinctive features.

1

A patchworkJacques Schwetz, a Russian émigré who became a prolific tropical medicine researcher. For somebody to be considered a good doctor, two instruments were essential: a microscope, and a syringe for IV and SC injections. We will see that there were other similarities with the French colonies, but also a few interesting distinctive features.

1

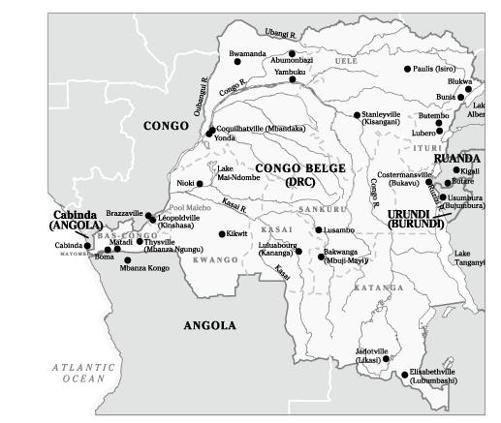

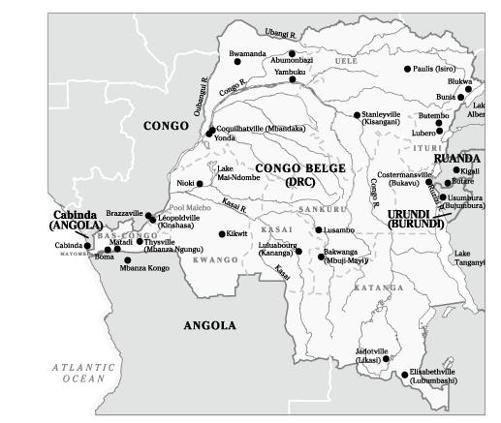

The first health reports available in the archives start in 1908, the year the colony was bought by Belgium. The health system was rudimentary with small hospitals in

Boma,

Léopoldville and

Stanleyville (

Map 6

), mostly to provide care to the Europeans. In separate premises, basic care was offered to the soldiers of the

Force Publique and some other Africans: mainly the treatment of sleeping sickness with early drugs. The largest facility was the 125-bed

Hôpital des Noirs in Boma, the capital, where basic surgery was available. A similar hospital existed in Léo, also with an operating room, while patients with sleeping sickness were treated in the nearby

lazaret

.

Patients with syphilis or yaws were given IV arsenicals as early as 1910, by which time there were forty-seven medical doctors in the colony. In the mining areas, private

companies built their own hospitals to care for their workers. Smaller government facilities were developed, with forty clinics or hospitals by 1914.

2

Boma,

Léopoldville and

Stanleyville (

Map 6

), mostly to provide care to the Europeans. In separate premises, basic care was offered to the soldiers of the

Force Publique and some other Africans: mainly the treatment of sleeping sickness with early drugs. The largest facility was the 125-bed

Hôpital des Noirs in Boma, the capital, where basic surgery was available. A similar hospital existed in Léo, also with an operating room, while patients with sleeping sickness were treated in the nearby

lazaret

.

Patients with syphilis or yaws were given IV arsenicals as early as 1910, by which time there were forty-seven medical doctors in the colony. In the mining areas, private

companies built their own hospitals to care for their workers. Smaller government facilities were developed, with forty clinics or hospitals by 1914.

2

Map 6

Map of the Belgian Congo (current names in brackets).

Map of the Belgian Congo (current names in brackets).

Mobile teams for the control of sleeping sickness were tested in the

Uele and

Kwango regions, and then generalised to other endemic areas. These were staffed by expatriate doctors and health agents, as well as Congolese

injecteurs

, people with no formal education who learned over a few months how to do injections and use a microscope to search for trypanosomes. Most trypanosomiasis patients were treated in their own villages by visiting

injecteurs

, who administered eight to twelve weekly injections of arsenicals. In between patients, the syringes and needles were simply rinsed with phenilated water. Later, when sleeping sickness was brought under control, the mobile teams also took care of other endemic diseases such as yaws

.

3

–

5

Uele and

Kwango regions, and then generalised to other endemic areas. These were staffed by expatriate doctors and health agents, as well as Congolese

injecteurs

, people with no formal education who learned over a few months how to do injections and use a microscope to search for trypanosomes. Most trypanosomiasis patients were treated in their own villages by visiting

injecteurs

, who administered eight to twelve weekly injections of arsenicals. In between patients, the syringes and needles were simply rinsed with phenilated water. Later, when sleeping sickness was brought under control, the mobile teams also took care of other endemic diseases such as yaws

.

3

–

5

Until the mid-1930s, a short course was given in Léopoldville for selected Catholic and Protestant missionaries to enable those working in isolated areas far from any hospital or health post to diagnose and treat a few infectious diseases: trypanosomiasis, yaws and syphilis

. They were given a microscope, syringes, needles and arsenical drugs

. These missionaries would provide valuable services to underprivileged populations but apparently they were not very good at sending reports. In 1926, there were ninety-three such centres run by volunteer missionaries

.

. They were given a microscope, syringes, needles and arsenical drugs

. These missionaries would provide valuable services to underprivileged populations but apparently they were not very good at sending reports. In 1926, there were ninety-three such centres run by volunteer missionaries

.

Progressively, the health system was developed as a patchwork of institutions run by the government, Catholic and Protestant missions, philanthropic organisations and private companies. To encourage physicians to go to the Congo, newly qualified Belgian doctors who signed a five-year contract were exempted from their two-year military service. By 1940, there were 302 medical doctors in the Congo: 161 employed by the government, 81 by private companies, 49 by missions or philanthropic institutions and 11 in private practice.

In contrast with the French colonies, WWII had little impact on the resources available for health services in the Congo, which functioned like an independent country, exporting large quantities of rubber and minerals needed for the allied war industry. A few doctors and nurses accompanied the 10,000-strong

Force Publique units which fought against the Italians in

Ethiopia and spent a year in

Egypt, but the vast majority of healthcare providers remained in the Congo. Health research continued, and a special journal was published so that new ideas could be disseminated while the colony was cut off from

Antwerp

.

In contrast with the French colonies, WWII had little impact on the resources available for health services in the Congo, which functioned like an independent country, exporting large quantities of rubber and minerals needed for the allied war industry. A few doctors and nurses accompanied the 10,000-strong

Force Publique units which fought against the Italians in

Ethiopia and spent a year in

Egypt, but the vast majority of healthcare providers remained in the Congo. Health research continued, and a special journal was published so that new ideas could be disseminated while the colony was cut off from

Antwerp

.

The development of the health system accelerated after the war, when Belgium felt it had a moral debt towards the Congo, and the annual reports detail an impressive list of capital investments. During the 1950s, ninety-six district hospitals, each with between 120 and 200 beds, were built, and 10% of the colony’s regular budget was spent on health care. In 1958, just before the Belgian Congo became independent, there were 2,815 health institutions of all kinds (general hospitals, maternity hospitals, dispensaries, health posts, etc.) with 85,000 hospital beds, more than in the rest of Africa put together, staffed by 703 medical doctors and 1,239 expatriate nurses, but only 128 Congolese medical assistants and 990 Congolese registered nurses. To a large extent, the increases in the number of cases of various diseases which we will review followed this advancement in the availability of health services.

6

6

Starting in the early 1920s, the annual reports of the public health system improved in quality, as did the coverage of the country’s population. However, while doctors in the public sector consistently provided data about the number of cases of such and such a disease treated during the previous year, their colleagues in mission hospitals or private companies (the largest of which operated their own healthcare system for their workers and dependants, who in some areas constituted the majority of the population) rarely did so until the early 1930s. Even in the public sector, the cases treated in rural dispensaries without medical supervision were not always tabulated. The incidence data should thus be interpreted as being indicative only of major trends.

As in French territories, sleeping sickness dominated the first few decades of the Belgian Congo. Here again, it is plausible that colonisation and the mixing of populations facilitated the transmission of the parasite. As the public health system increased its reach and implemented

case-finding activities following

Jamot’s model, ever-increasing numbers of cases were diagnosed and treated.

In 1920 in the

Kikwit territory, a few hundred kilometres east of Léo, 8,922 cases were diagnosed in a single year. As the mobile teams moved eastward into the

Kasaï region, other high-prevalence communities were identified, where up to 70% of inhabitants were found to have sleeping sickness, very much like in Cameroun. At some point, overwhelmed by the

situation, short of trained microscopists able to spend long periods of time looking for trypanosomes in lymph node aspirates or blood,

Schwetz, the head of the mission, decided to do something very unusual: all patients with enlarged cervical lymph nodes were treated without any parasitological assay being performed. In 1924, out of 69,298 cases nationwide, about 20,000 were these ‘suspect’ cases. Two years later, there were 39,033 suspects among the 64,015 new cases reported

. Whether or not these individuals indeed had trypanosomiasis, they received injectable trypanocidal drugs. The practice was discontinued shortly thereafter, and treatment given only to patients with a confirmed diagnosis. In the 1920s, data also took into consideration cases diagnosed during the previous years that needed to receive further treatment, either because they were relapsing or simply to consolidate the initial treatment. Starting in 1930, only new cases with parasitologically confirmed disease were reported. The evolution of the incidence of sleeping sickness in the Congo is shown in

Figure 15

. As in the French colonies, control measures proved very effective and the number of confirmed cases decreased from 36,030 in 1930 to 1,218 in 1958, the last year for which an annual report was produced. Thus the opportunities for the transmission of blood-borne viruses during the treatment of sleeping sickness were significant mostly during the first three decades of the twentieth century

.

1

,

7

,

8

case-finding activities following

Jamot’s model, ever-increasing numbers of cases were diagnosed and treated.

In 1920 in the

Kikwit territory, a few hundred kilometres east of Léo, 8,922 cases were diagnosed in a single year. As the mobile teams moved eastward into the

Kasaï region, other high-prevalence communities were identified, where up to 70% of inhabitants were found to have sleeping sickness, very much like in Cameroun. At some point, overwhelmed by the

situation, short of trained microscopists able to spend long periods of time looking for trypanosomes in lymph node aspirates or blood,

Schwetz, the head of the mission, decided to do something very unusual: all patients with enlarged cervical lymph nodes were treated without any parasitological assay being performed. In 1924, out of 69,298 cases nationwide, about 20,000 were these ‘suspect’ cases. Two years later, there were 39,033 suspects among the 64,015 new cases reported

. Whether or not these individuals indeed had trypanosomiasis, they received injectable trypanocidal drugs. The practice was discontinued shortly thereafter, and treatment given only to patients with a confirmed diagnosis. In the 1920s, data also took into consideration cases diagnosed during the previous years that needed to receive further treatment, either because they were relapsing or simply to consolidate the initial treatment. Starting in 1930, only new cases with parasitologically confirmed disease were reported. The evolution of the incidence of sleeping sickness in the Congo is shown in

Figure 15

. As in the French colonies, control measures proved very effective and the number of confirmed cases decreased from 36,030 in 1930 to 1,218 in 1958, the last year for which an annual report was produced. Thus the opportunities for the transmission of blood-borne viruses during the treatment of sleeping sickness were significant mostly during the first three decades of the twentieth century

.

1

,

7

,

8

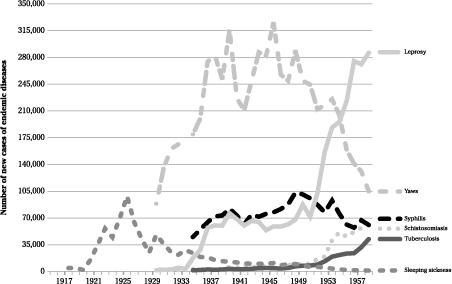

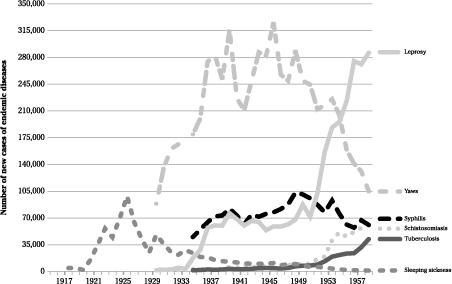

Figure 15

Number of new cases of endemic diseases in the Belgian Congo.

Number of new cases of endemic diseases in the Belgian Congo.

For other endemic diseases, the quality of the health information system improved considerably when, aware that the rational organisation and evaluation of disease control activities required an accurate view of the overall epidemiological situation, medical authorities prompted the colony’s governor to issue edicts that forced all healthcare institutions, regardless of their nature, to provide reports on priority diseases. The treatment of some infectious diseases was made compulsory and free. Yaws was the first for which comprehensive information became available in 1930, soon followed by syphilis and tuberculosis.

The Congo’s annual reports contained little information about treatments. In general, it seems that therapeutic strategies did not differ much from those adopted in AEF and Cameroun.

For leprosy, on top of

chaulmoogra another medicinal product was used:

hydnocarpus oil, various preparations of which were administered IV, but

methylene blue and

Caloncoba

were also popular for a while

.

For

syphilis, in addition to the injections of arsenical or bismuth-containing drugs (‘specific treatment’), ointments were applied on the lesions.

9

–

11

For leprosy, on top of

chaulmoogra another medicinal product was used:

hydnocarpus oil, various preparations of which were administered IV, but

methylene blue and

Caloncoba

were also popular for a while

.

For

syphilis, in addition to the injections of arsenical or bismuth-containing drugs (‘specific treatment’), ointments were applied on the lesions.

9

–

11

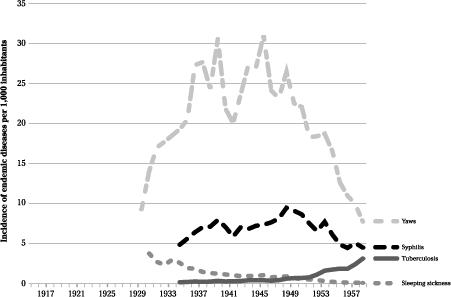

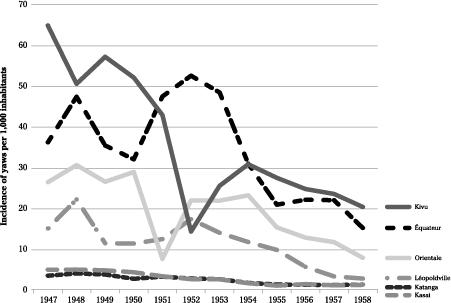

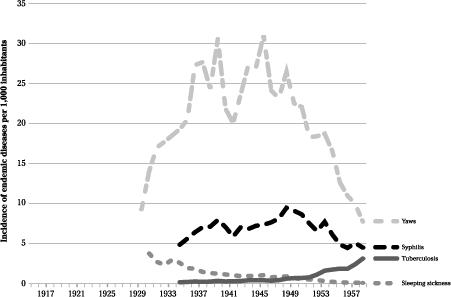

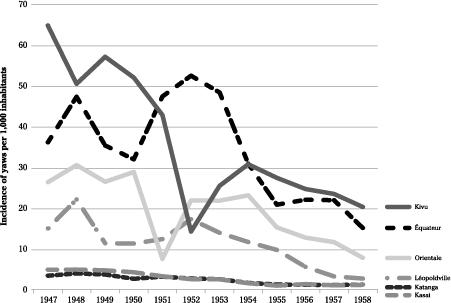

As shown in

Figures 15

and

16

, by far the most common endemic disease treated with injectable drugs was yaws, peaking at 325,000 cases in 1945. Its incidence varied dramatically between regions. The highest was in the

Costermansville province in the eastern part of the country (later known as

Kivu), while yaws was uncommon in

Katanga and

Kasaï (

Figure 17

). One of the high-incidence areas was the

Mayombe part of

Bas-Congo, the only region of the country inhabited by the

Pan troglodytes troglodytes

.

12

,

13

Figures 15

and

16

, by far the most common endemic disease treated with injectable drugs was yaws, peaking at 325,000 cases in 1945. Its incidence varied dramatically between regions. The highest was in the

Costermansville province in the eastern part of the country (later known as

Kivu), while yaws was uncommon in

Katanga and

Kasaï (

Figure 17

). One of the high-incidence areas was the

Mayombe part of

Bas-Congo, the only region of the country inhabited by the

Pan troglodytes troglodytes

.

12

,

13

Figure 16

Annual incidence of endemic diseases in the Belgian Congo.

Annual incidence of endemic diseases in the Belgian Congo.

Figure 17

Annual incidence of yaws in various regions of the Belgian Congo.

Annual incidence of yaws in various regions of the Belgian Congo.

Even with the early arsenic- or bismuth-based drugs, the treatment of

yaws was so effective, with the skin lesions rapidly regressing, that it was considered a useful public relations measure to attract the natives to the healthcare system, where more important diseases could be diagnosed and treated

. The incidence of syphilis was about one third that of yaws, and this STD seemed to have been less common than in the French colonies. This may have reflected an incidence that was truly lower, or perhaps differences in the diagnostic approaches and more rigorous identification of clinically diagnosed cases through more intense medical supervision. There was relatively little regional variation in the incidence of

syphilis.

yaws was so effective, with the skin lesions rapidly regressing, that it was considered a useful public relations measure to attract the natives to the healthcare system, where more important diseases could be diagnosed and treated

. The incidence of syphilis was about one third that of yaws, and this STD seemed to have been less common than in the French colonies. This may have reflected an incidence that was truly lower, or perhaps differences in the diagnostic approaches and more rigorous identification of clinically diagnosed cases through more intense medical supervision. There was relatively little regional variation in the incidence of

syphilis.

Schistosomiasis was rarely diagnosed initially, exceeding the 10,000 mark only in 1949. Most early patients were treated with IV

tartar

emetic, as in Egypt. The number of cases reported increased to 40,000–60,000 in the 1950s, but an oral drug artistically called

Nilodin (this disease was common in the

Nile delta) became popular and may have prompted more dynamic

case-finding. Schistosomiasis was prevalent mostly in the eastern end of the country, far from the areas inhabited by the central chimpanzee

.

14

tartar

emetic, as in Egypt. The number of cases reported increased to 40,000–60,000 in the 1950s, but an oral drug artistically called

Nilodin (this disease was common in the

Nile delta) became popular and may have prompted more dynamic

case-finding. Schistosomiasis was prevalent mostly in the eastern end of the country, far from the areas inhabited by the central chimpanzee

.

14

For leprosy, the number of cases reported included a mix of prevalent cases accumulated over the years, and new cases diagnosed within the previous twelve months. The statistics reported those under treatment, loosely defined, and most patients remained in that category for years even if they only had their wounds dressed. There were important geographic variations in the prevalence of leprosy, which was less common in the

Mayombe,

Bas-Congo and Léopoldville areas. The introduction of

sulphone drugs in the early 1950s revolutionised its treatment: oral dapsone was given to patients treated in a leprosarium while fortnightly injections were used for outpatients, who accounted for 86% of cases

.

15

–

16

Mayombe,

Bas-Congo and Léopoldville areas. The introduction of

sulphone drugs in the early 1950s revolutionised its treatment: oral dapsone was given to patients treated in a leprosarium while fortnightly injections were used for outpatients, who accounted for 86% of cases

.

15

–

16

Annual reports from the Belgian Congo provided relatively little information about malaria, presumably because the disease was so common that no public health intervention targeting this scourge could be contemplated. Fatalism prevailed. Most deaths occurred among young children, often at home rather than in a health institution. The number of malaria cases reported by government health services increased from 66,038 in 1940 to 938,477 in 1958. This probably did not reflect any genuine change in incidence, but only the degree of penetration and accessibility of health services. The high prevalence of asymptomatic malaria parasitaemia made these statistics somewhat meaningless. In areas where 50% of all healthy looking children have malaria parasites in their blood almost year round, any patient with any febrile illness who gets a blood smear done would have a 50% probability of being smear-positive. Who knows when the febrile episode is really caused by malaria? Based on the prevalence of parasitaemia or splenomegaly (an enlarged spleen) measured during systematic surveys, malaria was most common in the Congo basin and less so in the hilly areas in the east.

Antimalarial treatments were used massively and some of these were injectable drugs, mostly IV quinine.

17

–

21

Antimalarial treatments were used massively and some of these were injectable drugs, mostly IV quinine.

17

–

21

The therapeutic virtues of quinine, used by the first physician who worked in Léopoldville (1885–7), were known before the aetiological agent of malaria was identified. Oral quinine was used for the

prevention of malaria by Europeans, and proved the most effective intervention in reducing the mortality of colonists in central Africa. The investment in tropical medicine and disease control interventions for the natives eventually paid off: by 1940, the mortality of Europeans in the Congo was marginally higher than that of their kin in Belgium. The plant from which quinine is extracted was grown in the

Kivu province so the colony became self-sufficient

.

22

,

23

prevention of malaria by Europeans, and proved the most effective intervention in reducing the mortality of colonists in central Africa. The investment in tropical medicine and disease control interventions for the natives eventually paid off: by 1940, the mortality of Europeans in the Congo was marginally higher than that of their kin in Belgium. The plant from which quinine is extracted was grown in the

Kivu province so the colony became self-sufficient

.

22

,

23

The only large-scale immunisation was against smallpox; in the 1950s, between two and five million doses were administered annually. It is thus apparent that, across the entire colony, interventions for the control of sleeping sickness before 1930, and against yaws and to a lesser extent against syphilis after 1930, as well as the parenteral treatment of malaria in hospitals and dispensaries, provided the best opportunities for the iatrogenic transmission of blood-borne agents, including SIV

cpz

/HIV-1. Focally, the potential role of each disease varied with the local epidemiology and disease control strategies, as we will see shortly for Léopoldville.

cpz

/HIV-1. Focally, the potential role of each disease varied with the local epidemiology and disease control strategies, as we will see shortly for Léopoldville.

Other books

Petrella at 'Q' by Michael Gilbert

The Creative Fire: 1 (Ruby's Song) by Brenda Cooper

Rattled by Kris Bock

The Assassin: (Mortal Beloved Time Travel Romance, #2) by Pamela DuMond

The Path of the Sword by Michaud, Remi

Heat by Jamie K. Schmidt

Murder at the FBI by Margaret Truman

The Tanglewood Terror by Kurtis Scaletta

Heart of a Viking by Samantha Holt