The Origins of AIDS (16 page)

Read The Origins of AIDS Online

Authors: Pepin

The largest ever iatrogenic epidemic

HCV infection in central Africa

Inoculation hepatitis

At the turn of the century, studies in Egypt demonstrated that the iatrogenic transmission of another blood-borne virus, HCV, could reach a massive scale. Of course Egypt is not inhabited by

P.t. troglodytes

, so HIV-1 could not possibly have emerged in the Middle East. But as an example of the potential for well-intentioned disease control interventions to transmit blood-borne viruses, the Egyptian experience is hard to beat.

31

P.t. troglodytes

, so HIV-1 could not possibly have emerged in the Middle East. But as an example of the potential for well-intentioned disease control interventions to transmit blood-borne viruses, the Egyptian experience is hard to beat.

31

Schistosomiasis is caused by a parasite with a complex life cycle, which is acquired during exposure to water inhabited by the snails that constitute its intermediate host. In the most common form of schistosomiasis, adult worms live in the blood vessels around the rectum, causing bloody diarrhoea, or liver fibrosis when their eggs manage to travel up to the liver. There is also a variety in which the adult worms live around the bladder, with the eggs excreted into the urine rather than the stools; such patients pass blood in their urine.

Schistosomiasis used to be highly endemic in the Nile delta, where mass treatment campaigns with parenteral drugs led to the HCV infection of millions of individuals.

The use of tartar emetic, a very old drug against schistosomiasis, had begun in 1921, and the ministry of health started organising large-scale campaigns in the early 1950s. Between 1964 and 1982, more than two million injections of tartar emetic were administered each year to 250,000 patients. On average they received

ten to twelve weekly IV injections through hastily sterilised syringes and needles, boiled for only one or two minutes or not at all. In specialised centres, more than 500 patients could be treated in an hour. Tartar emetic was not very effective: many patients relapsed or were re-infected, and had to receive further cycles of the drug. The historical information is congruent with what was calculated using the same molecular approaches as we reviewed for HIV-1, which indicated an exponential growth in the number of HCV-infected individuals between 1940 and 1980

.

32

–

33

The use of tartar emetic, a very old drug against schistosomiasis, had begun in 1921, and the ministry of health started organising large-scale campaigns in the early 1950s. Between 1964 and 1982, more than two million injections of tartar emetic were administered each year to 250,000 patients. On average they received

ten to twelve weekly IV injections through hastily sterilised syringes and needles, boiled for only one or two minutes or not at all. In specialised centres, more than 500 patients could be treated in an hour. Tartar emetic was not very effective: many patients relapsed or were re-infected, and had to receive further cycles of the drug. The historical information is congruent with what was calculated using the same molecular approaches as we reviewed for HIV-1, which indicated an exponential growth in the number of HCV-infected individuals between 1940 and 1980

.

32

–

33

For the whole country, 22% of individuals aged ten to fifty years became infected with HCV. HCV prevalence is lower (6–8%) in residents of

Cairo and Alexandria, but reaches 19% to 28% in Upper, Middle and Lower Egypt. Prevalence is higher among the older age groups, who were exposed repeatedly to schistosomiasis treatments. In Lower and Middle Egypt, more than 50% of individuals aged forty or more are HCV-seropositive. In all these regions, there was a correlation between exposure to schistosomiasis treatment and HCV infection

. The same interventions also led to the iatrogenic transmission of

HBV, but in this case the relationship was blurred by the other modes of transmission of HBV

.

31

Cairo and Alexandria, but reaches 19% to 28% in Upper, Middle and Lower Egypt. Prevalence is higher among the older age groups, who were exposed repeatedly to schistosomiasis treatments. In Lower and Middle Egypt, more than 50% of individuals aged forty or more are HCV-seropositive. In all these regions, there was a correlation between exposure to schistosomiasis treatment and HCV infection

. The same interventions also led to the iatrogenic transmission of

HBV, but in this case the relationship was blurred by the other modes of transmission of HBV

.

31

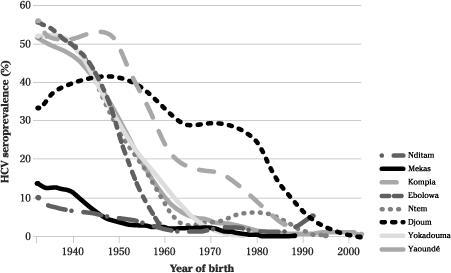

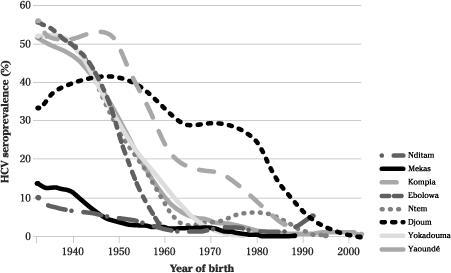

Now let us get geographically closer to the heart of the story. After Egypt, central Africa has the highest HCV prevalence in the world: 6.0% of adults overall and 13.8% in Cameroon. In several areas of Cameroon, more than 40% of elderly individuals became HCV-seropositive. What epidemiologists call a cohort effect (the exposure to a given pathogen varying according to the year of birth) was demonstrated, with HCV prevalence reaching 40–50% among people born before 1945, about 15% for those born in 1960, and 3–4% for younger individuals born after 1970. In several studies, HCV prevalence plateaued at the same point, corresponding to a year of birth around 1930–5 (

Figure 9

). So most of the parenteral transmission of HCV must have occurred between 1930 and 1970.

34

–

42

Figure 9

). So most of the parenteral transmission of HCV must have occurred between 1930 and 1970.

34

–

42

Molecular clock analyses confirmed this conclusion and revealed that in Cameroon, Gabon and the Central African Republic, the number of HCV-infected individuals started increasing exponentially between 1920 and 1940, continuing for two or three decades. Since the

heterosexual transmission of HCV is relatively ineffective, this indicates massive parenteral transmission of at least one blood-borne virus in the very areas inhabited by the

P.t. troglodytes

source of HIV-1. This parenteral transmission took place during the colonial era, starting at the same time, give or take a few years, as SIV

cpz

successfully emerged into human populations to become HIV-1. It is hard to believe that this represents merely a strange coincidence.

42

,

43

heterosexual transmission of HCV is relatively ineffective, this indicates massive parenteral transmission of at least one blood-borne virus in the very areas inhabited by the

P.t. troglodytes

source of HIV-1. This parenteral transmission took place during the colonial era, starting at the same time, give or take a few years, as SIV

cpz

successfully emerged into human populations to become HIV-1. It is hard to believe that this represents merely a strange coincidence.

42

,

43

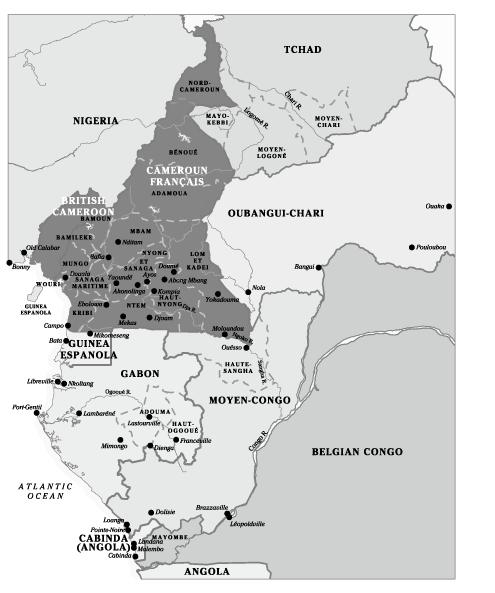

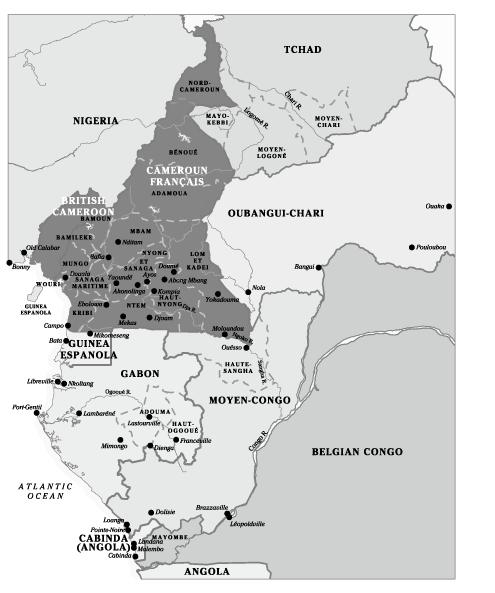

In Cameroon, populations with a high HCV prevalence come from

Yaoundé or villages in the southern rain forest (

Figure 9

and

Map 5

), and prevalence is much lower in the north. A similar north–south gradient in HCV prevalence was observed in territories that used to be part of AEF, with a low prevalence in

Tchad and the Central African Republic and a high prevalence in Gabon

. This means that the diseases during the treatment of which transmission of HCV occurred were more common in the southern rain forests than in the arid north

.

42

–

45

Yaoundé or villages in the southern rain forest (

Figure 9

and

Map 5

), and prevalence is much lower in the north. A similar north–south gradient in HCV prevalence was observed in territories that used to be part of AEF, with a low prevalence in

Tchad and the Central African Republic and a high prevalence in Gabon

. This means that the diseases during the treatment of which transmission of HCV occurred were more common in the southern rain forests than in the arid north

.

42

–

45

Figure 9

Prevalence of HCV infection at various sites in Cameroon by year of birth.

Prevalence of HCV infection at various sites in Cameroon by year of birth.

Adapted from Pepin.

46

46

Map 5

Map of Cameroun Français and the four colonies that comprised the Afrique Équatoriale Française federation.

Map of Cameroun Français and the four colonies that comprised the Afrique Équatoriale Française federation.

It seems plausible that not all medical injections carried the same risk of HCV transmission. Again, data gathered during studies of healthcare workers occupationally exposed to their patients’ blood can be informative. Healthcare workers exposed to HCV experience a higher risk of infection when a hollow-bore needle had been placed in the index patient’s vein and when they sustain a deeper injury; these risk factors

presumably reflect the higher number of viral particles accidentally inoculated

. Extrapolating to the potential iatrogenic transmission between patients, the risk must have been higher with IV, intermediate with IM, and lower with SC or ID injections. And obviously the risk must have been proportional to the total number of injections received. The same conclusions can be extended to the transmission of HIV.

In Cameroon, researchers looked for HIV-1 nucleic acids in discarded needles and syringes that had been used on HIV-infected patients less than six hours earlier. One third of the syringes used for IV injections contained detectable virus, versus only 2% of those used for IM injections

.

47

–

49

presumably reflect the higher number of viral particles accidentally inoculated

. Extrapolating to the potential iatrogenic transmission between patients, the risk must have been higher with IV, intermediate with IM, and lower with SC or ID injections. And obviously the risk must have been proportional to the total number of injections received. The same conclusions can be extended to the transmission of HIV.

In Cameroon, researchers looked for HIV-1 nucleic acids in discarded needles and syringes that had been used on HIV-infected patients less than six hours earlier. One third of the syringes used for IV injections contained detectable virus, versus only 2% of those used for IM injections

.

47

–

49

Now we will go back in time to try to assess what medical doctors and nurses working in central Africa in the first half of the twentieth century could have known concerning the potential transmission of viruses during medical care. Presumably, understanding these risks might have made them more careful. We can assume that the level of understanding among these pioneers of tropical medicine was no higher than among their counterparts working in Europe. Most of the knowledge about blood-borne viruses that eventually trickled down to medical practitioners in Africa originated from Europe.

During this period of interest, little was known about viruses in general and even less about putative viruses potentially causing hepatitis. Unlike bacteria and parasites, viruses were too small to be seen during direct or stained microscopic examinations of specimens. Their culture required the support of cells, while for bacteria an agar plate with the right nutrients would suffice. Nor were clinicians at the time able to measure liver enzymes in the blood, which is essential to the diagnosis of hepatitis, whatever its aetiology. These enzymes are released when there is inflammation in the liver.

In practice, ‘hepatitis’ was diagnosed when a patient developed jaundice for which there was no other apparent explanation (in the tropics, this investigation would include negative smears for malaria). Cases of hepatitis not severe enough to cause jaundice would be missed, while some patients with other conditions associated with jaundice were misdiagnosed as having hepatitis. The diagnoses were pretty reliable, however, when outbreaks occurred: if dozens or hundreds of somehow-related patients developed jaundice within a limited time frame, there was no doubt that this corresponded to hepatitis caused by an infectious agent

.

.

‘Inoculation hepatitis’ or ‘serum hepatitis’ began to be described in textbooks from the 1940s as appearing after various medical interventions including, in Europe, the treatment of syphilis with arsenic-based

drugs, usually administered as a series of weekly IV injections. Clinicians distinguished between early arsenical hepatitis, occurring around day 9 and presumed to be drug-related, and late hepatitis, occurring after about 100 days, which was thought to be infectious.

50

–

55

drugs, usually administered as a series of weekly IV injections. Clinicians distinguished between early arsenical hepatitis, occurring around day 9 and presumed to be drug-related, and late hepatitis, occurring after about 100 days, which was thought to be infectious.

50

–

55

Before WWII, only 1% of syphilitics treated with IV arsenical drugs developed jaundice, but wartime conditions and shortages led to a quicker turnaround of syringes and needles

. In several military clinics in Britain, between 50% and 75% of men treated for syphilis developed jaundice! Similar epidemics occurred in civilian hospitals after the virus had been introduced by returning soldiers who had received initial doses of some IV drug in a military clinic. This was attributed to the re-use of glass syringes, which were in short supply, so they could not be boiled between patients (it would have taken too long for the syringes to cool down before they could be handled again); they were put into a disinfectant briefly or they were merely rinsed with water. Before a drug was injected IV, the nurse had to aspirate a small quantity of blood to make sure that the needle was properly located within a vein. When the drug was pushed into the vein, a minute quantity of blood remained in the syringe and the needle, some of which ended up being injected into the vein of the next patient(s).

54

–

57

. In several military clinics in Britain, between 50% and 75% of men treated for syphilis developed jaundice! Similar epidemics occurred in civilian hospitals after the virus had been introduced by returning soldiers who had received initial doses of some IV drug in a military clinic. This was attributed to the re-use of glass syringes, which were in short supply, so they could not be boiled between patients (it would have taken too long for the syringes to cool down before they could be handled again); they were put into a disinfectant briefly or they were merely rinsed with water. Before a drug was injected IV, the nurse had to aspirate a small quantity of blood to make sure that the needle was properly located within a vein. When the drug was pushed into the vein, a minute quantity of blood remained in the syringe and the needle, some of which ended up being injected into the vein of the next patient(s).

54

–

57

When outbreaks of jaundice were described after the treatment of syphilis and other infections with

penicillin, then a revolutionary drug, it became more and more difficult to attribute these cases to anything other than a transmissible agent

. Furthermore, a viral cause was suspected when it became apparent that the nurses who administered the IV injections, as well as the laboratory technicians who handled the blood samples sent for testing, were themselves at risk of developing jaundice. These outbreaks certainly corresponded to infection with HBV, since most cases of acute infection with HCV do not develop overt jaundice. Obviously, to reach a risk of hepatitis of 50–75%, a vicious circle with exponential amplification of HBV was created. A first HBV-infected patient transmitted the virus to a few more; each of these second-generation cases infected a few additional patients, and so on.

58

penicillin, then a revolutionary drug, it became more and more difficult to attribute these cases to anything other than a transmissible agent

. Furthermore, a viral cause was suspected when it became apparent that the nurses who administered the IV injections, as well as the laboratory technicians who handled the blood samples sent for testing, were themselves at risk of developing jaundice. These outbreaks certainly corresponded to infection with HBV, since most cases of acute infection with HCV do not develop overt jaundice. Obviously, to reach a risk of hepatitis of 50–75%, a vicious circle with exponential amplification of HBV was created. A first HBV-infected patient transmitted the virus to a few more; each of these second-generation cases infected a few additional patients, and so on.

58

Around 1942, batches of a yellow fever vaccine which had been suspended in human serum (obtained from medical students) during its production caused 50,000 cases of jaundice among American civilians and soldiers. With this massive epidemic, the second major form of viral hepatitis was given its current name. Strongly associated with

injections and not displaying any seasonality, it became known as hepatitis B, to distinguish it from the other form of infectious hepatitis,

hepatitis A, which was not associated with injections but displayed marked seasonal variations in incidence. When US army veterans who had developed hepatitis in 1942 after receiving the yellow fever vaccine were tested in 1985, four decades later, 97% of them had antibodies against HBV, as did 73% of those who had been vaccinated without developing overt hepatitis, compared to only 13% of those not vaccinated. If those who were infected but did not develop jaundice are added to the symptomatic cases, it can be estimated that 330,000 vaccine recipients were iatrogenically infected with HBV. Other vaccines, blood sampling through a common syringe (in clinics for diabetics or in a sanatorium), transfusions and administration of convalescent sera,

plasma or injectable drugs were in turn all recognised as causing hepatitis B

.

59

–

60

injections and not displaying any seasonality, it became known as hepatitis B, to distinguish it from the other form of infectious hepatitis,

hepatitis A, which was not associated with injections but displayed marked seasonal variations in incidence. When US army veterans who had developed hepatitis in 1942 after receiving the yellow fever vaccine were tested in 1985, four decades later, 97% of them had antibodies against HBV, as did 73% of those who had been vaccinated without developing overt hepatitis, compared to only 13% of those not vaccinated. If those who were infected but did not develop jaundice are added to the symptomatic cases, it can be estimated that 330,000 vaccine recipients were iatrogenically infected with HBV. Other vaccines, blood sampling through a common syringe (in clinics for diabetics or in a sanatorium), transfusions and administration of convalescent sera,

plasma or injectable drugs were in turn all recognised as causing hepatitis B

.

59

–

60

There is no evidence that medical officers working in central Africa in colonial times became aware of these risks. The risk of inoculation hepatitis was not mentioned in any of the reports of the health systems of AEF and Cameroun that will be reviewed in the

next chapter

, while in the Belgian Congo its first description was published in 1953. Acute HCV infection is often asymptomatic or causes non-specific symptoms, without overt jaundice, and could not possibly have been recognised by the colonial clinicians

. Infection with HBV is nearly universal in central Africa and generally acquired during childhood (when it rarely causes jaundice), which leaves little potential for its iatrogenic transmission to adults, in contrast to Britain, where most adults treated for syphilis had hitherto not been infected with HBV and were susceptible to an iatrogenic infection. Furthermore, when iatrogenic HBV infection did occur in sub-Saharan Africa, symptoms would have developed after a one- to four-month incubation period, making it difficult for doctors to recognise that this was related to a previous episode of medical care

.

next chapter

, while in the Belgian Congo its first description was published in 1953. Acute HCV infection is often asymptomatic or causes non-specific symptoms, without overt jaundice, and could not possibly have been recognised by the colonial clinicians

. Infection with HBV is nearly universal in central Africa and generally acquired during childhood (when it rarely causes jaundice), which leaves little potential for its iatrogenic transmission to adults, in contrast to Britain, where most adults treated for syphilis had hitherto not been infected with HBV and were susceptible to an iatrogenic infection. Furthermore, when iatrogenic HBV infection did occur in sub-Saharan Africa, symptoms would have developed after a one- to four-month incubation period, making it difficult for doctors to recognise that this was related to a previous episode of medical care

.

Reports of health services in

Cameroun and

AEF give no indication regarding how re-usable syringes and needles were sterilised between patients or how many times a syringe/needle might be used on any given day. A textbook for nurses, written by the chief medical officer of

Gabon in 1931, gave instructions regarding how syringes and needles were to be sterilised, but these required an autoclave or a dry heat incubator, available only in hospitals and large health centres. What mobile teams and nurses working in small facilities without electricity

were expected to do was unclear. Most injections were given by practical nurses with limited scientific training. Given the huge caseloads, the sterilisation process may have been shortcut or bypassed, as in Egypt. We will see later that, at least in the Belgian Congo, syringes and needles were not even boiled between patients. It seems likely that this was the rule rather than the exception.

61

Cameroun and

AEF give no indication regarding how re-usable syringes and needles were sterilised between patients or how many times a syringe/needle might be used on any given day. A textbook for nurses, written by the chief medical officer of

Gabon in 1931, gave instructions regarding how syringes and needles were to be sterilised, but these required an autoclave or a dry heat incubator, available only in hospitals and large health centres. What mobile teams and nurses working in small facilities without electricity

were expected to do was unclear. Most injections were given by practical nurses with limited scientific training. Given the huge caseloads, the sterilisation process may have been shortcut or bypassed, as in Egypt. We will see later that, at least in the Belgian Congo, syringes and needles were not even boiled between patients. It seems likely that this was the rule rather than the exception.

61

With this in mind, to estimate their potential role in the transmission of blood-borne viruses and particularly SIV

cpz

/HIV-1 and HCV, we will review the major disease control programmes implemented in central Africa from 1921 to 1959, the topic of the next two chapters.

cpz

/HIV-1 and HCV, we will review the major disease control programmes implemented in central Africa from 1921 to 1959, the topic of the next two chapters.

Other books

Doc: A Novel by Mary Doria Russell

September Song by William Humphrey

In Too Deep by Michelle Kemper Brownlow

Giada's Feel Good Food by Giada De Laurentiis

Federal Paranormal Unit Bundle: Shape Shifter Paranormal Romance by Milly Taiden

Orcs: Bad Blood by Stan Nicholls

BLACK in the Box by Russell Blake

No Place Like Home by Dana Stabenow

Joe Pitt 5 - My Dead Body by Huston, Charlie