unSpun (8 page)

Chapter 5

Facts Can Save Your Life

G

ETTING THE FACTS RIGHT IS IMPORTANT

. I

T CAN SAVE YOUR

money, your health, even your freedom.

We're not exaggerating one bit. Consider the story of Daniel Bullock, a California physician who got spun by a sleazy tax-shelter promoter and then received some unwelcome visitors carrying badges and guns. “My seventeen-year-old daughter answered the door to some armed federal agents from the [IRS] criminal investigation division,” he recalled. “That was a bad day.” And worse followed: Bullock lost his medical license and served eight months in a federal prison camp, all because he had failed to check the facts when a smooth-talking promoter sold him what turned out to be a criminal tax-evasion scam.

Bullock was a churchgoing orthopedic surgeon from Mount Shasta, California, who did volunteer work in Central America. But like a lot of people, he hated paying his taxes, and resented the stories he had heard about how others avoided taxes entirely. “When I encountered someone with âinside information' on how the very wealthy avoid taxes I was all ears,” Bullock told a Senate subcommittee in 2002, after he had started serving his sentence. “He had a good story, a well used and âsuccessful' strategy, hundreds of clients and legal opinions in support of his program.” Bullock fell into the “I don't want to hear it” trap. He was so convinced that his benefactor had discovered a legal way to avoid paying taxes that he failed to look for evidence to the contrary.

Bullock bought into a preposterous scheme that sent his earnings on a round trip to the Caribbean through a series of offshore banks and “nonprofit” trusts. These entities returned the money to him by paying his mortgage and other personal living expenses. That made Bullock's money hard for the IRS to trace but did nothing to erase his legal obligation to pay taxes on it. It was just a scam, as was clear to Bullock's bookkeeper, who eventually turned him in to the IRS. The judge who sentenced Bullock thought it should have been apparent to anybody. “Any ten-year-old would know this was obviously illegal,” he said.

Bullock might have avoided prison by practicing a little “active open-mindedness” and asking himself how likely it was that the IRS would actually allow this kind of dodge. He might also have called someone who didn't stand to make money on the scheme, unlike the promoter who collected thousands of dollars in fees for his “services.” Bullock's own lawyer or accountant might have quickly set him straight about what a dim view the IRS takes of sham transactions and international money-laundering. Bullock might also have conducted a quick Internet search on the name of the promoter who sold him the scheme, which might have turned up the fact that the man had already been convicted on seven counts of aiding and assisting the filing of false tax returns. Today, a simple search for the term “tax schemes” brings up page after page of official warnings about similar scams and the prosecutions that often result. Try it yourself.

Bullock's story shows that letting bad information go unchallenged can have grave consequences. He is not alone. Thousands of people have used tax-evasion schemes like the one he fell for, and while most don't go to prison they all risk being forced to pay fines, big penalties, and interest on top of the back taxes when they are caught. Some may know they are engaging in criminal activity, but we suspect the majority are like Bullock, actively obtuse when it comes to matters that improve their tax returns. And it hardly matters whether we have been deceived by somebody else or have failed to check out our own dubious assumptions. The price for getting the facts wrong is the same whether we are deceived or self-deceived, misinformed or disinformed, spun by others or spun by the pictures in our head. The message here is simple: facts matter.

The “Grey Goose Effect”

Most bad information won't land you in jail or ruin your career, but much of it will cost you money. For proof of that, look no further than the snake-oil hustles we mentioned in Chapter 1. We can be manipulated into spending too much money in more subtle ways, too. For example, we tend to think of higher-priced goods as being of better quality than lower-priced goods; but while “You get what you pay for” may be common folk wisdom, it isn't always true. In the 1950s, Pepsi competed with Coca-Cola by selling its soda at half the price of Coke and advertising “twice as much for a nickel.” But more people bought Pepsi after it

raised

its price, a lesson not lost on other marketers. A formerly obscure brand of Scotch whiskey also increased its sales by raising its price, giving its name to what is now known as the Chivas Regal effect.

Today it might better be called the Grey Goose effect, after the hot-selling French vodka that came on the U.S. market in 1997 selling for $27 a bottle, nearly triple the price of the top-of-the-market Smirnoff brand. Grey Goose sales exploded. Vodka is officially defined by U.S. government regulations as “neutral spiritsâ¦without distinctive character, aroma, or taste,” so it is hard to see how one vodka can be three times better than another on any objective basis. The drink is basically distilled alcohol cut with water.

Now, when our sharp-eyed Random House editor, Tim Bartlett, first saw this he objected: “Expensive vodkas on average are significantly smoother than cheap ones, which taste like rubbing alcohol.” We're quite sure that's how it seems to Tim and many others, but they're not judging only on the basis of what their taste buds tell them. They are also taking into account, perhaps unconsciously, the price they have paid for the vodka, the amount of advertising they have seen telling them that the expensive vodka is superior and is drunk by sophisticated, in-the-know people, and even the fancy design of the bottle. We might agree that the Grey Goose bottle is prettier than the Smirnoff bottle, but that has nothing to do with what the bottles contain. Try comparing brands without any predisposition to think one is better than the other, and see what happens. The New York City artist (and blogger) Andrea Harner did just that. She and her husband, Jonah Peretti, invited over some friends in March 2006 for a blindfold test comparing Smirnoff to Grey Goose. Result: eight of sixteen correctly picked which was which. That's exactly 50 percent, the same result you would expect from tossing a coin. Harner's testers did much better telling regular Coke from regular Pepsi: 70 percent got the cola right.

Taste is subjective, and you might well conclude that the illusion of better taste is worth paying for. Or perhaps your palate is more sensitive than the palates of Ms. Harner and her friends. Our point is, simply, that higher price predisposes us to think that a product is better, even when it's not. With respect to vodka, soda, or any other beverage, you can't know for sure what really tastes better unless you do a blindfold test yourself. As Ms. Harner wrote: “The point is that this challenge was A LOT harder than people expected. A LOT. I dare you to give it a try.” At the very least, her test results suggest you could pour Smirnoff into a Grey Goose bottle and your friends would never know the difference.

The price-equals-quality fallacy is exploited by others besides the booze industry. Many second-tier private colleges and universities make sure the “sticker price” of their tuition is close to (or even higher than) Harvard's, Princeton's, and Yale's, in the hope that parents and students will take the mental shortcut of equating price with quality.

Consumer Reports

magazine, which conducts carefully designed tests on all sorts of products from automobiles to toasters to TV sets, often finds lower-priced goods to be of higher quality than those costing much more. For example, in a comparison of upright vacuum cleaners on the magazine's website in 2006, the $140 Eureka Boss Smart Vac Ultra 4870 was rated better overall than the $1,330 Kirby Ultimate G Diamond Edition or the $700 Oreck XL21-700. The Eureka was better than the highly advertised $500 Dyson DC15. Dyson claims that its vacuum “never lose[s] suction,” and maybe that's true. But the independent testers at

Consumer Reports

found that the Eureka did a better job of cleaning carpets, at less than a third the price.

The mismatch between price and quality has been apparent for a long time. Back in 1979, the University of Iowa business professor Peter C. Riesz checked the

Consumer Reports

ratings of 679 different packaged foods over fifteen years. He found that the correlation between quality and price “is near zero.” In other words, price had very little if anything to do with quality; the cheaper product was the better one about half the time.

So don't get spun by price tags. Shop around, and keep in mind that sometimes less expensive options are good enough, and in some cases just as good as the pricier alternative. It pays to check the facts.

Selling False Hope

Getting facts wrong not only can cost you money or get you in trouble with the law: it can put you in the hospital, or worse. Consider the harrowing story of a cancer patient named Chuck Hysong, of Hendersonville, North Carolina. According to his wife, Pamela, he'd been improving while taking a new medication prescribed by his oncologist. But at nine

P.M

. on April 12, 2002, he took a preparation called Optimizer ENG-C, sold to him by a man recommended by a relative who was skeptical of doctors and a believer in “alternative” medicine.

Mrs. Hysong says she had begged her husband not to take the “optimizer” preparation. For one thing, the man who sold it “told my husband that he has a 100 percent cure rate for bone cancer,” Mrs. Hysong recalls. That was obviously too good to be true, and there were other clear warning signs. The seller refused to list the ingredients of his “supplements,” Mrs. Hysong says, adding that he also demanded $5,000 payment, in advance, not covered by any medical insurance. She refused to pay, but the relative put up the first $2,000. “Chuck was desperate,” Mrs. Hysong recalls. “He was still a relatively young man, and he wasn't ready to go, and he was ready to try anything within what he considered reason.” That's typical of many seriously ill people for whom science offers little hope; they fall prey to quackery and medical fraud, losing money and sometimes suffering further damage to their health.

Mrs. Hysong describes what happened when her husband took the $2,000 Optimizer preparation:

“By nine-thirty, he had uncontrollable diarrhea; almost constant discharge from his nose; he was hallucinating that he had smoke coming off his body; he was burning hot; he made uncontrollable noises; he was nauseated; he was scared; and he was angry. After about an hour of diarrhea, when he tried to stand, he could not do so without bracing himself. He could not walk back to bed.”

Mr. Hysong was rushed to the hospital, where he spent the night. He was left “dehydrated, weak, and ashamed that he had been sucked into this,” according to his wife. His earlier improvement ceased. “About a week later he started going south again,” Mrs. Hysong said. “I don't know if it was coincidence, or the stress to his body.” Chuck Hysong died three months later. Cancer killed him, but as Mrs. Hysong describes it, the pills added to his suffering and weakened him in his final days.

The red flags still fly. Robert Dowling, the man Mrs. Hysong says sold the pills to her husband, runs something he calls the North Carolina Institute of Technology. Though he claims no formal medical training, in 2006 his websiteâwww.cancercured.orgâclaimed to have a method of finding and curing breast cancer before it develops. Dowling had done business in South Carolina before coming north, but South Carolina authorities shut down his operation in September 2001 after the death of a client, a seventy-one-year-old woman suffering from stomach cancer. A few months earlier, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration had warned Dowling that he was illegally selling an unapproved medical device by marketing “Bioscan 2010” home kits, which could supposedly predict disease. Dowling moved on to an even smaller town, giving his address as Hot Springs, North Carolina.

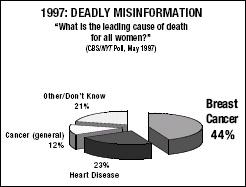

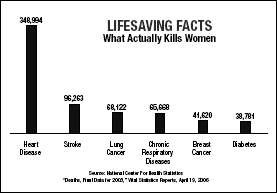

What Really Kills Women?

Far more lethal than any quack healer, however, is the misinformation about our bodies and our health that millions of us carry around unquestioned. As recently as 1997, for example, adult women and men were most likely to name breast cancer as the leading killer of women, which isn't close to being true and never has been. The plain fact is women are

nine times

more likely to die of heart disease, and more than twice as likely to die from stroke. Lung cancer kills far more women than breast cancer, and so do other chronic lung diseases, such as emphysema. Furthermore, many of these deaths could be avoided if women had a more accurate mental picture of their true health risks and acted accordingly.

To be sure, the attention to breast cancer has done a great deal of good, making women more likely to detect cancers at a curable stage through regular mammograms and self-examinations. That's one reason breast cancer deaths have been declining. But the hard facts imply that women should be many times more concerned about heart attacks, stroke, and lung disease than about breast cancer. They should educate themselves about the warning signs of heart attack (these signs are somewhat different in women than in men, by the way), and consider preventive diet and exercise habits. For the millions of women who smoke, the facts might convince them to try quitting. Everybody knows smoking increases the risk of lung disease and heart attack, but a more accurate picture of how

many

women die from these could provide smokers with added motivation to drop the habit. In short, facts can save lives.

It's easy to see why so many had the wrong idea, not because of any intentional deception but because breast cancer gets enormous attention in the news media and that's where most people get their information. When a CBS/

New York Times

poll asked people where they learned most about health-related issues, only one in ten said from a doctor; six in ten said they learned most from television, newspapers, or magazines. However, what reporters and editors find newsworthy often is a poor measure of what people really need to know. We get spun by mistaking how often we hear about something for how often it really occurs. For example, as we've already mentioned, the more crime stories people see on TV, the more crime-ridden they believe their communities to be, even when crime is declining. Psychologists call this effect the availability heuristic, a mental bias that gives more weight to vividness and emotional impact than to actual probability.

Ironically, breast cancer gets so much attention partly because so many women

survive

it and become advocates, producing and participating in publicity-grabbing events such as the annual Race for the Cure. That's not a bad thing, as we've noted. But the deadlier risks deserve even more publicity and attention.

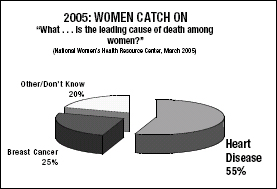

A poll taken in March 2005 showed 55 percent of women correctly identified heart disease as their leading killer. The percentage of respondents who get this question right had doubled since 1997. But that change required a massive campaign by the federal government as well as the American Heart Association and other groups. First Lady Laura Bush made women's heart disease a personal project, and the government's National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute scored big in 2003 with its “Red Dress Project,” hooking up with the glitzy Mercedes Benz Fashion Week and nineteen designers. Yet 25 percent of women still think breast cancer is a bigger threat than heart disease. No quack or con man told them thatâit is simple misinformation. But that misinformation can kill themâand getting the facts straight can save their lives.