unSpun (7 page)

The “Root for My Side” Trap

Related to the “pictures in our heads” trap is the “root for my side” trap. There's evidence that our commitment to a cause not only colors our thinking but also affects what we seeâand don't seeâas we observe the world around us.

Psychologists have known about this phenomenon for a long time. In 1954, Albert Hastorf and Hadley Cantril published a classic study of how Princeton and Dartmouth football fans saw a penalty-ridden game in which the Princeton quarterback was taken off the field with a broken nose and a mild concussion and a Dartmouth player later suffered a broken leg. They found that 86 percent of the Princeton students said that Dartmouth started the rough play, but only 36 percent of the Dartmouth students saw it that way. The researchers asked, “Do you believe the game was clean and fairly played or that it was unnecessarily rough and dirty?” The results: 93 percent of Princeton fans said “rough and dirty,” compared with only 42 percent of Dartmouth fans. When shown films of the game and asked to count actual infractions by Dartmouth players, Princeton students spotted an average of 9.8, twice as many as the 4.3 infractions noted by Dartmouth students.

Were the Dartmouth and Princeton fans deliberately distorting what they saw? Probably not. Hastorf and Cantril went so far as to say that people don't just have different attitudes about things, they actually see different things: “For the âthing' simply is

not

the same for different people whether the âthing' is a football game, a presidential candidate, Communism or spinach.”

We don't know about spinach, but when it comes to presidential candidates a recent study using brain-scanning technology supports the notion that people really do see things differently, depending on whom they back. The scans also suggest that emotion takes over and logic doesn't come into play. (See “This is your brain on politics” box.)

A closely related effect is what researchers call the hostile media phenomenon. Three Stanford University researchers demonstrated this in 1985 by showing pro-Arab and pro-Israeli audiences identical news accounts of the massacre of several hundred persons in the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps near Beirut, Lebanon, in 1982. Each side detected more negative than positive references to their side, and each side thought the coverage was likely to sway neutral observers in a direction hostile to them. Why? Probably because content that agrees with our own views simply seems true and thus not very noteworthy, while material that counters our biases stands out in our minds and makes us look for a reason to reject it. So, to a conservative, news with a conservative slant is fair; to a liberal, news with a liberal slant is fair; and to both, there is something unfair somewhere in any news program that tries to balance alternative points of view.

This Is Your Brain on Politics

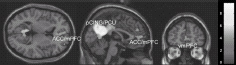

During the 2004 presidential campaign, the Emory University psychologist Drew Westen and his colleagues conducted brain scans of fifteen Bush supporters and fifteen Kerry supporters, who were asked to evaluate statements attributed to each candidate. The researchers told the subjects that Kerry had reversed his position on overhauling Social Security, and they said Bush flip-flopped on his support for the former chief executive of Enron, Ken Lay.

Not surprisingly, each group judged the other's candidate harshly but let its own candidate off fairly easyâclear evidence of bias. More interesting was what the brain scans showed. “We did not see any increased activation of the parts of the brain normally engaged during reasoning,” Westen said in announcing his results. “What we saw instead was a network of emotion circuits lighting up.”

Fig. 1: Emotional centers active when processing information unfavorable to the partisan's preferred candidate

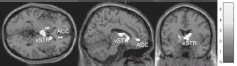

Furthermore, after the partisans had come to conclusions favorable to their candidates, their brain scans showed activity in circuits associated with reward, rather as the brains of addicts do when they get a fix. “Essentially, it appears as if partisans twirl the cognitive kaleidoscope until they get the conclusions they want, and then they get massively reinforced for it,” Westen said.

Fig. 2. Reward centers active when processing information that gets the partisan's preferred candidate off the hook

Westen's experiment supplies physical evidence that emotionally biased thinking may be hard-wired into our brains.

Images from Drew Westen,

Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience(2006),

MIT Press Journals, © by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Psychologists call this phenomenon confirmation bias, and it not only colors how we see things, but how we reason as well. David Perkins, a professor of education at Harvard, has aptly called it “myside bias.” In studies of how people reason when asked to think about a controversial issue, Perkins observed a strong tendency for people to come up with reasons favoring their own side, and not even to think about reasons favoring the other. His test subjects offered three times more considerations on their own side of an issue as they did against their position, and that count included arguments they brought up just for the sake of shooting them down.

The University of Pennsylvania psychologist Jonathan Baron found a classic example of myside bias in a

Daily Pennsylvanian

student article in favor of abortion rights, which said: “If government rules against abortion, it will be acting contrary to one of the basic rights of Americans,â¦the right to make decisions for oneself.” The author of that sentence was oblivious to the thought that the other side sees abortion as equivalent to murder, and that laws against homicide also interfere with “the right to make decisions for oneself” when the decision is to commit murder.

When Baron asked fifty-four University of Pennsylvania students to prepare for a discussion of the morality of abortion, he found, as expected, that they tended to list arguments on only one side of the question. What was even more revealing, the students who made one-sided arguments also rated the arguments of others as being of better quality when those other arguments were all on one side, too, even arguments on the opposing side. He concluded: “People consider one-sided thinking to be better than two-sided thinking, even for forming one's own opinion on an issue.”

General Norman Schwarzkopf fell into the confirmation bias trap after leading U.S. forces to one of the most lopsided military victories in history during the Gulf War in 1991. As Colin Powell tells it in his autobiography,

My American Journey,

Schwarzkopf appeared at a news conference with video that he said showed a U.S. smart bomb hitting Iraqi Scud missile launchers. When Powell informed him that an analyst had identified the targets as fuel trucks, not missile launchers, Schwarzkopf exploded. “By God, those certainly were Scuds. That analyst doesn't know what he's talking about. He's just not as good as the others.” Powell says later examination showed that the analyst was right. Schwarzkopf just couldn't see it. Believing that his forces were really hitting Scud launchers, he was open only to evidence that confirmed his belief.

Even scholars are affected by this powerful bias. In the 1980s, the National Institute of Education (NIE) asked six scholars to conduct an analysis of existing research into the effects of desegregated schools. Two of the scholars were thought to favor school integration, two to oppose it, and two to be neither opponents nor proponents. Sure enough, the differences in their findings were consistent with their ideological predispositions. The differences were slight, which is a testament to the power of the scientific method to rein in bias. But the bias was there nonetheless.

Once you know about confirmation bias, it is easy to detect in others. Confirmation bias was at work when CIA analysts rejected evidence that Iraq had really destroyed its chemical and biological weapons and gave weight only to signs that Saddam Hussein retained hidden stockpiles. Confirmation bias explains why so many people believe in psychics and astrologers: they register only the apparently accurate predictions and ignore those that miss. Confirmation bias explains why, once someone has made a bad first impression on a date or during a job interview, that impression is so hard to live down. And it is because of confirmation bias that good scientists try actively to

disprove

their own theories: otherwise, it would be just too easy to see only the supporting evidence.

To avoid this psychological trap, apply a bit of the scientific method to political claims and marketing messages. When they sound good, ask yourself what fact could prove them untrue and what evidence you may be failing to consider. You may find that a partisan or dogmatic streak is keeping you from seeing facts clearly.

The “I Know I'm Right” Trap

There's evidence that the more misinformed we are, the more strongly we insist that we're correct. In a fascinating piece of research published in 2000, the political psychologist James H. Kuklinski and his colleagues reported findings from a random telephone survey of 1,160 Illinois residents. They found few who were very well informed about the facts of the welfare system: only 3 percent got more than half the questions right. That wasn't very surprising, but what should be a warning to us all is this: those holding the least accurate beliefs were the ones expressing the highest confidence in those beliefs.

Of those who said correctly that only 7 percent of American families were getting welfare, just under half said they were very confident or fairly highly confident of their answer. But 74 percent of those who grossly overestimated the percentage of those on welfare said they were very confident or fairly highly confident, even though the figure they gave (25 percent) was more than three times too high. This “I know I'm right” syndrome means that those who most need to revise the pictures in their heads are the very ones least likely to change their thinking. Of such people, it is sometimes said that they are “often in error but never in doubt.”

The “Close Call” Trap

Psychological research shows that when we are confronted with tough decisions and close calls, we tend to exaggerate the differences. The psychologist Jack Brehm demonstrated this in a famous experiment published in 1956. He had women rate eight different products such as toasters and coffeemakers, then let them keep oneâbut allowed them to choose between only two of the products. He set up some of the decisions as “close calls,” between two products the women had rated alike; others were easy calls, with wide differences in ratings. After the women had made their choices, Brehm asked them to rate the products again. This time, women who had been forced to make a tough choice tended to be more positive about the product they had picked and less positive about the one they had rejected. This change was less evident among women who had made the easy call.

Psychologists call this the “spreading of alternatives” effect, a natural human tendency to make ourselves feel better about the choices we have made, even at the expense of accuracy or consistency. We crave certainty, and don't want to agonize endlessly about whether we made the right call. This mental habit helps us avoid becoming frozen by indecision, but it also can make changing our minds harder than need be when the facts change, or when we have misread the evidence in the first place. Once in a while we need to ask, “Would I feel this way if I were buying this product (or hearing this argument) for the first time? Have new facts emerged since I made my initial decision?”

It's easy to fall into traps like the ones we've described here, because people manage most of the time on automatic pilot, using mental shortcuts without really having to think everything through constantly. Consider a famous experiment published by the Harvard psychologist Ellen Langer in 1978. She and her colleagues repeatedly attempted to cut in front of persons about to use a university copying machine. To some they said, “Excuse me. May I use the Xerox machine, because I'm in a rush?” They were allowed to cut in 94 percent of the time. To others, the cheeky researchers said only, “Excuse me. May I use the Xerox machine?,” without giving any reason. These succeeded only 60 percent of the time. So far, that's what you would probably expect: we're likelier to accommodate someone who has a good reason for a request than someone who just wants to push ahead for their own personal convenience. But here's the illuminating point: Langer showed that giving an obviously bogus reason worked just as well as giving a good one. When Langer's cohorts said, “Excuse me, may I use the Xerox machine, because I have to make some copies?” they were allowed to cut in 93 percent of the time.

“Because I have to make some copies” is really no reason at all, of course. Langer's conclusion is that her unwitting test subjects reacted to the word “because” without really listening to or thinking about the reason being offered; they were in a state she called “mindlessness.”

Others have demonstrated the same zombielike tendency, even among university students who supposedly are smarter than average. Robert Levine, a psychology professor at California State University, Fresno, tried different pitches during a campus bake sale. Asking “Would you like to buy a cookie?” resulted in purchases by only two out of thirty passersby. But his researchers sold six times more cookies when they asked “Would you like to buy a cookie? It's for a good cause.” Of the thirty passersby who were asked that question, twelve bought cookies. And none even bothered to ask what the “good cause” was.

Marketers use the insights from such studies against us. An Internet-based salesman named Alexi Neocleous tells potential clients that Langer's study shows “because” is “a magic word [that] literally forces people to buckle at the knees and succumb to your offer.” He adds, “The lesson for you is, give your prospects the reason why, no matter how stupid it may seem to YOU!”

The lesson we should draw as consumers and citizens is just the opposite: watch out for irrelevant or nonexistent reasons, and make important decisions attentively. “Mindlessness” and reliance on mental shortcuts are often fine; we probably won't go far wrong buying the most popular brand of soap or toothpaste even if “best-selling” doesn't really mean “best.” Often the most popular brand is as good a choice as any other. But when we're deciding on big-ticket items, it pays to switch on our brains and think a bit harder.

How can we break the spell? Research shows that when people are forced to “counterargue”âto express the other side's point of view as well as their ownâthey are more likely to accept new evidence rather than reject it. Try what Jonathan Baron, of the University of Pennsylvania, calls active open-mindedness. Baron recommends putting initial impressions to the test by seeking evidence against them as well as evidence in their favor. “When we find alternatives or counterevidence we must weigh it fairly,” he says in his book

Judgment Misguided.

“Of course, there may sometimes be no âother side,' or it may be so evil or foolish that we can dismiss it quickly. But if we are not open to it, we will never know.”

That makes sense to us. We need to ask ourselves, “Are there facts I don't know about because I haven't looked for them? What am I missing here?” Otherwise, we're liable to end up like Mrs. Keech's UFO cultists, preaching with utter conviction that Guardians from the Planet Clarion really do exist, or like the blustering General Schwarzkopf angrily denying the truth about those burned-out tanker trucks. It's better to be aware of our own psychology, to know that our brains tend to “light up” to reinforce our existing beliefs when we hear our favorite candidates or positions challenged. To avoid being deceived (or deceiving ourselves) we have to make sure the pictures in our heads come as close to reflecting the world outside as they reasonably can.