unSpun (3 page)

Bin Laden Baloney

Implied deception worked against Bush, too. Michael Moore's highly partisan movie

Fahrenheit 9/11

left many viewers, including the authors of this book, with the impression that President Bush had approved a special flight to allow relatives of Osama bin Laden who lived in the United States to get out of the country while U.S. airspace was still closed in the days immediately following 9/11. The movie also strongly implied that the bin Laden clan escaped without being questioned by U.S. officials about where Osama himself might be found, or about any prior knowledge of the attack. A close reading of Moore's script shows that Moore never stated that as a fact, but his implied message was unmistakable. Over newsreel footage of passengers stranded by the 9/11 grounding of all commercial flights, Moore is heard saying, “Who wanted to fly? No one. Except the bin Ladens.” That is followed by footage of an airplane taking off, accompanied by the booming strains of The Animals' rock song “We Gotta Get Out of This Place.” Then Moore says, “It turns out that the White House approved planes to pick up the bin Ladens.” But as the final report of the independent 9/11 Commission later documentedâpossibly to clarify the widely held misimpression Moore had createdâthe flight carrying the bin Laden relatives didn't depart until a full week after airspace was reopened to commercial flights. Furthermore, the FBI questioned a number of the family members before they were allowed to leave.

Late in the campaign, Moore's sly insinuation was exceeded in mendacity by the Media Fund, an independent, Democratic-leaning group headed by former Bill Clinton deputy chief of staff Harold Ickes. It spent nearly $60 million in an attempt to defeat Bush. Part of that sum went to a radio ad saying that the bin Laden family had been allowed to fly “when most other air traffic was grounded.” In fact, the bin Laden flight was on September 20, and the Federal Aviation Administration had allowed commercial air traffic to resume at eleven

A.M

. on September 13.

The radio ad also said, “We don't know whether Osama's family members would have told us where bin Laden was hiding. But thanks to the Bush White House, we'll never find out.” That was utterly false. The FBI had questioned the family membersâalmost two dozen of them. Here's some of what the 9/11 Commission's final report said on that point:

Twenty-two of the 26 people on the Bin Ladin flight were interviewed by the FBI. Many were asked detailed questions. None of the passengers stated that they had any recent contact with Usama Bin Ladin or knew anything about terrorist activity [pp. 557â58].

False Radio Ad

MEDIA FUND: “Flight Home”

Announcer:

After nearly 3,000 Americans were killed, while our nation was mourning the dead and the wounded, the Saudi royal family was making a special request of the Bush White House. As a result, nearly two dozen of Osama bin Laden's family members were rounded upânot to be arrested or detained, but to be taken to an airport, where a chartered jet was waitingâ¦to return them to their country. They could have helped us find Osama bin Laden. Instead the Bush White House had Osama's family flown home, on a private jet, in the dead of night, when most other air traffic was grounded.

We don't know whether Osama's family members would have told us where bin Laden was hiding. But thanks to the Bush White House, we'll never find out.

Furthermore, the 9/11 Commission said that the bin Laden family members might not have been interviewed had they simply departed the country in the usual way, rather than leaving on a charter flight with special White House clearance:

Having an opportunity to check the Saudis was useful to the FBI. This was because the U.S. government did not, and does not, routinely run checks on foreigners who are leaving the United States. This procedure [chartering a flight] was convenient to the FBI, as the Saudis who wished to leave in this way would gather and present themselves for record checks and interviews, an opportunity that would not be available if they simply left on regularly scheduled commercial flights [p. 557].

Fifty-two percent of the people we polled found it truthful that the Bush administration let the bin Laden family leave the United States while airspace was still closed. In this case it was mostly Democrats who were deceived (perhaps because they wanted to be; more on that later): 70 percent of them found the false statement truthful. But nearly half the independents were taken in, too: 48 percent found it truthful. And more than one third of Republicansâ36 percentâalso bought the myth that Bush let the bin Laden clan skedaddle when airports were still closed.

Nonstop Deception

Political deception doesn't stop when elections are over. Even in nonelection years, interest groups now weigh in on legislative and other policy debates with TV ad campaigns on which they spend tens of millions of dollars. In 2005:

⢠In a radio ad by a conservative group called Freedom-Works, former Republican House leader Dick Armey misleadingly claimed a proposed reform of asbestos litigation set aside “billions ofâ¦tax dollars as payoffs to trial lawyers.” In fact, trial lawyers had opposed the measure; it would have cut into their legal fees.

⢠A liberal group called Campaign for America's Future ran a grossly misleading newspaper ad claiming that Wall Street stockbrokers stood to get a $279 billion windfall from the individual Social Security accounts that Bush outlined in some detail in 2005. FactCheck.org dug up evidence that brokers could expect less than two penniesâyes, penniesâfor every $1,000 invested.

⢠A conservative group called Let Freedom Ring, Inc., ran a pair of TV ads pushing for a $4 billion security fence along the Mexican border. The ad showed footage of the 9/11 attack on the World Trade Center with a voice-over claiming “illegal immigration from Mexico provides easy cover for terrorists.” But none of the 9/11 hijackers entered the United States through Mexico, and all entered legally. More persons from suspect Muslim nations actually slip in over the Canadian border than from Mexico.

No Respect

As we hope is becoming clear, respect for facts isn't a major concern in the advertising industry, and is far too rare in politics.

“Surely it is asking too much to expect the advertiser to describe the shortcomings of his product,” wrote David Ogilvy in his

Confessions of an Advertising Man.

The legendary adman said he was “continuously guilty of suppressio veri.” That translates from the Latin as “suppression of truth,” and it sums up a lot of what we see in commercial advertising. The art of advertising, in fact, has been described as the art of promoting a false illusion. “I've never worked on a product that was better than another. They hardly don't exist,” the advertising executive George Lois told CBS News's

60 Minutes

in 1981. “So what I have to do is, I have to create an imagery about that product.”

The historian Doris Kearns Goodwin gives a good example of the attitude we are talking about in her 1991 book

Lyndon Johnson and the American Dream.

She reports that LBJ sometimes claimed that his great-great-grandfather had died at the Alamo, and at other times said he died at the Battle of San Jacinto, in which Sam Houston routed the Mexican dictator Antonio López de Santa Anna and won independence for Texas. The latter claim was particularly unlikely, since Houston lost only nine men killed in the twenty-minute battle. And, obviously, both claims could not be true. In fact, Goodwin learned that the great-great-grandfather to whom Johnson referred actually “died at home, in bed.” When she challenged LBJ he said, “God damn it, why must all those journalists be such sticklers for details?”

Goodwin explains that Johnson was engaging in the old Texas tradition of the “tall tale.” She quotes a literary historian, Marcus Cunliffe, who wrote that as the “tall tale” spread west it entered political oratory during an era when politics was among the few sources of entertainment: “Was it true? The question had little meaning. What mattered was the story itself.”

The same notion surfaced again in 2006 when the author James Frey was exposed as having fabricated portions of his supposedly truthful memoir

A Million Little Pieces.

Oprah Winfrey, who had promoted the best-selling book to her devoted audience, at first defended the “underlying message of redemption” in the book, implying that it was acceptable to lie about the small stuff in the service of a laudable goal. But two weeks later she publicly apologized on her own show. “I left the impression that the truth does not matter,” she said. “And I am deeply sorry about that, because that is not what I believe.”

That's not what we believe either, and we'd like to see fewer tall tales and more respect for factual accuracy in politics, advertising, and public life in general. Count us among the “sticklers” who so irritated LBJ. The attitude we'd prefer was shown by the future Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts in 1986, when he was a young aide to President Ronald Reagan. Somebody had drafted a joke for Reagan to drop into his annual economic message: “I just turned 75 today, [but that's] only 30 degrees Celsius.” That was incorrect: 75 degrees Fahrenheit is only 23.9 degrees on the Celsius scale. Reporters for

The New York Times,

poring over Roberts White House memos during Roberts's confirmation battle in 2005, found that he had corrected the president's prepared remarks. When Reagan actually delivered them, he said: “I heard a reference to my age this morning. I've heard a lot of them recently. I did turn 75 today, but remember, that's only 24 Celsius.”

Unprotected Public

How do the deceivers get away with it? Truth-in-advertising laws give some protection from false claims in

commercial

advertising, but a lot still get through. A false ad can run for many months before regulators get it off the air. And even then, advertisers have learned to weasel-word their commercials so that their claims are literally accurate but still misleading. We'll have more to say about that later in this book. As for politicians, they actually have a legal right to lie in their television and radio ads. There is no federal law requiring truth in political ads at all, and the few states that have attempted such laws have had them overturned or found them ineffective.

Some believe that politicians can be sued for defamation if they stray too far from the truth, and they think that provides some protection to voters. It doesn't. The courts move too slowly for that, and they rightly give candidates the full benefit of the free-speech protections of the U.S. Constitution. So lawsuits for false political claims are rare, and do voters no good. In a classic case from the past, during the 1964 presidential election Barry Goldwater, the Republican candidate, sued

FACT

magazine for claiming he had a severely paranoid personality and was psychologically unfit for the high office. Goldwater won the lawsuit, but the verdict came down long after he had lost the election to Lyndon Johnson in a landslide. So for any who voted against Goldwater because they believed the magazine, the courts were no help. The attitude of the courts is that voters are grown-ups who deserve to hear all sides of an argument, even the falsehoods, and that it's up to them to sort it out for themselves.

Citizens might expect to find political spin aggressively debunked by the news media, but in our view they get far too little of that. There was a brief flurry of “factcheck”-style reports in the final weeks of the 2004 presidential campaign, but that was a departure from the norm. The fact that some news organizations were actually calling dubious claims “false” or “misleading” was itself considered newsworthy. The PBS

NewsHour

devoted a segment to the phenomenon on its evening newscast. Alas, the media fact-checking quickly faded once the election was over. The hard reality is that the public is exposed to enormous amounts of deception that go unchallenged by government regulators, the courts, or the news media. We voters and consumers must pretty much fend for ourselves if we know what's good for us. In coming chapters, we'll show you how.

Chapter 2

A Bridesmaid's Bad Breath

Warning Signs of Trickery

P

OOR

E

DNA

. S

HE WAS ONE GREAT-LOOKING WOMAN, SO IT WAS

strange that she couldn't land a husband. And nobody would tell her why she was “often a bridesmaid but never a bride.” Edna wasn't real, but her story, part of the ad campaign begun in 1923 that made Listerine lucrative, offers a window into how we can be manipulated by appeals to our fears and insecurities.

The reason Edna was headed for spinsterhoodâaccording to the adsâwas breath so offensive that “even your best friends won't tell you.” The ploy worked: Lambert sold tanker loads of Listerine. In 1999,

Advertising Age

magazine named the “bridesmaid” ad one of the hundred top campaigns of the twentieth century.

The Listerine ads appealed to fear with a simple, unspoken message: use our product, or risk losing friends or even a future spouse because of putrid breath that you may not even know you have. Other Listerine ads played variations on the theme. In an ad from 1930, a dentist wonders why his patients have deserted him; he had never heard the whispers about his awful breath. The headline: “Do they say it of you?â

probably.

” Another ad, from 1946, shows a young man rejected at a job interview and asks, “In these days of fierce competition to get and hold a job, can you afford to take chances because of halitosis (unpleasant breath)?”

WARNING SIGN:

If It's Scary, Be Wary

F

EAR HAS BEEN A STAPLE TACTIC OF ADVERTISERS AND POLITICIANS

for so long that you'd think that we would have become better at detecting their use of it. But fear and insecurity can still cloud our judgment. To put the lesson in a nutshell: “If it's scary, be wary.”

The FUD Factor

Fear sells things other than mouthwash. In the 1970s, one of IBM's most talented computer designers left to make and market a new machine. Gene Amdahl's “Amdahl 470” mainframe computer was a direct replacement for IBM's System 370, then the market leader, but sales were less than expected. Amdahl found that many corporate customers were afraid to buy his product even though by all accounts it was cheaper, faster, and more reliable than the IBM machine. He accused his former employer of using “FUD”âhis acronym, meaning “fear, uncertainty, and doubt”âto discourage consumers from his new brand. Would Amdahl's company be around to support their hot new product? Would IBM retaliate somehow? Would corporate purchasers be fired for taking a risk if things went bad?

We see FUD being employed to sell all sorts of things. There are few Internet users who haven't run into frightening pop-up messages along the lines of this hit from 2004â05: “WARNING: POSSIBLE SPYWARE DETECTEDâ¦Spyware can steal information from your computer, SPAM your e-mail account or even CRASH YOUR COMPUTER!” Frightened recipients who clicked a link to “complete the scan” were taken to a website peddling a $39.95 product called SpyKiller, which promised to remove “all traces” of the fearsome spyware. But the Federal Trade Commission found this FUD-based pitch to be a lie. No scan had been performed before the message was sent, no spyware had been found, and the program didn't even work as advertisedâit failed to remove “significant amounts” of spyware. In May 2005, the FTC took the Houston-based marketer, Trustsoft, Inc., to court, and the company and its chief executive, Danilo Ladendorf, later agreed to pay $1.9 million to settle the case. Ladendorf was to sell his Houston residence to pay back what the FTC called “ill-gotten gains,” but by then tens of thousands of consumers had been tricked.

Bush's “Day of Horror”

The buildup to the 2003 invasion of Iraq showed a particularly able use of FUD. In his State of the Union address of January 28, 2003, President Bush said that Saddam Hussein was pursuing weapons of mass destruction and invited listeners to imagine what would have happened if Saddam had given any to the 9/11 hijackers: “It would take one vial, one canister, one crate slipped into this country to bring a day of horror like none we have ever known.” The previous September, Condoleezza Rice, who was then the national security adviser, had said on CNN that it wasn't clear how quickly Saddam could obtain a nuclear weapon, then added: “But we don't want the smoking gun to be a mushroom cloud.” With memories of September 11, 2001, still fresh, those appeals to fear helped generate overwhelming public support for the war. On March 17, 2003, three days before the war began, only 27 percent of those polled for

The Washington Post

said they opposed the war. A lopsided majority of 71 percent said they supported it, including 54 percent who said they supported it “strongly.”

Afterward, as we all know now, U.S. inspectors searched for months only to conclude that Saddam had actually destroyed his stockpiles of chemical and biological weapons years earlier. He had no active program to develop nuclear weapons. Bush's “day of horror” speech was as scary as scary gets. And many of usâthe president, the CIA, Congress, and much of the press and the publicâshould have been more wary, should have asked more questions, and should have demanded more evidence.

Some circumstances justify raising an alarm: it's appropriate to shout “Fire!” when flames really put lives or property in immediate danger. Our point here is that a raw appeal to fear is often used to cover a lack of evidence that a real threat exists, and should alert us to take a hard look at the facts. Are we being warned, or deceived?

WARNING SIGN:

A Story That's “Too Good”

W

E SHOULD APPROACH CLAIMS CAUTIOUSLY WHEN THEY ARE TOO

dramatic, especially when we want them to be true. Consider a case involving what we might call “destruction of mass weapons.”

The book

Arming America: The Origins of a National Gun Culture

was greeted with celebration by advocates of gun control. The author, Michael A. Bellesiles, a professor of history at Atlanta's Emory University, claimed that household gun ownership had been rare in colonial and preâCivil War America. Michael Barnes, the then president of Handgun Control, Inc. (now known as the Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence), lauded Bellesiles's “discovery” and proclaimed: “By exposing the truth about gun ownership in early America, Michael Bellesiles has removed one more weapon in the gun lobby's arsenal of fallacies against common-sense gun laws.”

If, indeed, weapons ownership wasn't widespread in colonial America, then the picture of a nation of “Minutemen” with muskets over the fireplace was false. This also meant the National Rifle Association would have less room to argue that the Second Amendment was written to guarantee the right of individuals to own guns privately, and not just to bear arms as members of a regulated militia. Bellesiles offered as proof what he described as a painstaking, ten-year study of 11,000 probate records showing what people owned when they died. Columbia University seemingly endorsed the finding, awarding Bellesiles's book the coveted Bancroft Prize in 2001.

For those favoring gun control, Bellesiles told a story that was way too good to be trueâliterally. “The data fit together almost too neatly,” noted Professor James Lindgren of the Northwestern University School of Law. After checking a portion of the same records on which Bellesiles said he had based his conclusions, Lindgren and his colleagues concluded that he had “repeatedly counted women as men, counted guns in about a hundred wills that never existed, and claimed that the inventories evaluated more than half of the guns as old or broken when fewer than 10% were so listed.” In eight different sets of probate records, guns appeared in 50 percent to 73 percent of estates left by men, figures several times higher than Bellesiles had claimed. Lindgren found guns were twice as common as Bibles in estates from 1774.

Other discrepancies were noted; for example, Bellesiles claimed to have examined probate records from San Francisco, but all such records had been destroyed in the 1906 earthquake and fire. Emory University placed Bellesiles on paid leave and asked a panel of outside historians to investigate. The investigators found “evidence of falsification” regarding the “vital” table summarizing Bellesiles's probate data and said “his scholarly integrity is seriously in question.” He resigned from Emory, still protesting that he was guilty of nothing worse than innocent mistakes. Nevertheless, in December 2002 Columbia University withdrew the Bancroft Prize, saying that Bellesiles had “violated basic norms of acceptable scholarly conduct.”

There was plenty of reason to question Bellesiles's data. Given how starkly it contradicted what had been accepted for two centuries, it amounted to an extraordinary claim demanding extraordinary proof. Gun-control advocates were too quick to swallow it because it seemed to help their cause, and they paid the price in embarrassment when the facts of Bellesiles's deception were uncovered. When a claim seems “too good,” it should be a warning to withhold judgment until we get a close look at the evidence.

Data in the Service of Ideology

Extravagant claims are just too easy to accept when they match biases. In 1991, we were told something shocking, which seemed to confirm the view that women are victims of a sexist society. In her book

The Beauty Myth,

Naomi Wolf claimed that 150,000 women die annually from anorexia nervosa. This was a preposterously high number, more than five times the number of Americans who died of AIDS that year, for example. But it strongly supported Wolf's thesis that women were suffering because of an impossible standard of beauty imposed by society.

The 150,000 figure was disputed in 1994 by Christina Hoff Sommers, a critic of the feminist movement, who said “the correct figure is less than 100.” While Sommers should be credited for debunking Wolf's wildly inaccurate claim, she, too, was way off, according to Harold Goldstein and Harry Gwirtsman of the Eating Disorders Program of the National Institute of Mental Health. They noted that between one half percent and one percent of the 28 million women between 15 and 29 years old were thought to have anorexia, and that a mortality rate of about 10 percent over a 20-year period was “generally accepted.” That would work out to roughly 1,000 deaths per year, Goldstein and Gwirtsman figured. They also cautioned against accepting “data in the service of ideology.” That's a notion we endorse. When the data square too nicely with your biases, always ask, “Is this dramatic story really true? Am I buying this just because I want it to be true? What's the evidence?”

WARNING SIGN:

The Dangling Comparative

“L

ARGER,” “BETTER,” “FASTER,” “BETTER-TASTING

.” A

DVERTISERS FREQUENTLY

employ such terms in an effort to make their product stand out from the crowd. In a recent ad, makers of New Ban Intensely Fresh Formula deodorant claimed it “keeps you fresher longer.” One might be forgiven for thinking they meant it keeps you fresher, longer than the competition. But, as a competitor complained to the Better Business Bureau's National Advertising Division, they meant fresher than Ban's old formulation.

Politicians are particularly able users of this technique. In the 2004 presidential campaign, George W. Bush's TV ads hammered away with this line: “[John] Kerry supported higher taxes over 350 times.” A voter might quite reasonably have thought this to mean that Kerry had voted to raise taxes an alarming number of times, but that implication was grossly misleading. Bush did not mean that Kerry had in every case voted to make taxes “higher” than they were at the time. Such votes were relatively rare. Employing a common political tactic, Bush counted every vote Kerry had cast

against a proposed tax cut,

which meant voting to leave taxes unchanged. He also padded the count by including many procedural votes on the same bills. Bush even counted some of Kerry's votes for Democratic tax cuts, reasoning that those would still leave taxes higher than the Republican alternatives. Thus, by means of twisted use of the dangling comparative, a vote for cutting taxes became a vote for “higher taxes.”

Bush was using the phrase “higher taxes” without answering the question “Higher than what?” A dangling comparative occurs when any term meant to compare two thingsâa word such as “higher,” “better,” “faster,” “more”âis left dangling without stating what's being compared. Bush used a dangling comparative to mischaracterize Kerry's actual record. Kerry did vote for several tax increases during his twenty years in the Senate, but nothing remotely close to 350. His voting record was consistent with his promise to repeal only part of Bush's tax cuts and to raise taxes only on persons earning more than $200,000 a year.

Please Mom, More Arsenic!

Just to be fair, we should note that the Democrats have been known to employ the dangling comparative with some skill themselves. In 2001, for example, President Bush was accused of trying to put “more arsenic” in drinking water. In April of that year, the Democratic National Committee ran a TV ad in which a little girl asks, “May I please have some more arsenic in my water, Mommy?” And at the January 4, 2004, debate among Democratic presidential hopefuls in Des Moines, Iowa, Representative Dick Gephardt of Missouri said the Bush administration “tried to put more arsenic in the water. We stopped them from doing it.”

But by “more arsenic” Democrats did not mean “more than is in the water now”; the disagreement was over how much to

reduce

arsenic levels. When Bush took office he suspended a regulation that President Clinton had proposed only days before the end of his term. This last-minute regulation would have reduced the federal ceiling on arsenic in drinking water from 50 parts per billion (ppb), where it had been since 1942, to 10 ppb. The Bush administration said it wanted to review the costs being imposed on small communities, estimated to be as high as $327 per household for some towns of fewer than 10,000 people. Bush administration officials considered a more flexible limit that would have allowed a limit of as high as 20 ppb in a few cases. That would have been double the limit proposed by Clinton but still a 60 percent reduction compared to the existing ceiling. Eventually, however, Bush accepted the 10 ppb level and the new limit went into effect in January 2006 exactly as Clinton had proposedâno earlier, no later. At no time did the Bush team propose to raise the limit above the existing level to allow “more arsenic.”

In both cases, the deceivers' central point may well have had a grain of merit, but rather than make an honest argument they invited the public to accept gross exaggerations. So when you hear a dangling comparative term such as “more” or “higher,” always ask, “Compared to what?” The answer may surprise youâand keep you from being fooled.

WARNING SIGN:

The Superlatives Swindle

J

UST AS COMPARATIVE WORDS SUCH AS “MORE” AND “HIGHER” ARE

warning signs, so are superlatives such as “most” and “highest” and claims such as “biggest in history” or “smallest ever.” In 2004 a pro-Bush group named the Progress for America Voter Fund ran a TV ad asking, “Has any president been dealt a tougher hand?” Their message was that Bush, because he inherited an economy on the verge of a downturn and had presided during the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, faced the toughest circumstances of any president in history. That's silly. Was Bush “dealt a tougher hand” than Abraham Lincoln, whose election prompted the breakup of the Union and who took office just six weeks before Confederates fired on Fort Sumter and began the Civil War? Tougher than Franklin Roosevelt, who took office during the Great Depression and later contended with Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941? Come on!

Another example of the “superlative swindle”: Republicans still persist in calling Bill Clinton's 1993 deficit reduction billâin Bush's wordsâ“the biggest tax increase in American history.” It wasn't, unless you count only raw dollars and disregard population growth, rising incomes, a growing economy, and inflation. Measured as a fraction of the entire economy, Clinton's 1993 increase was one sixth the size of Roosevelt's 1942 tax increase. That World War II levy was equal to $5.04 for every $100 of economic output, according to a paper prepared by a tax expert in Bush's own Office of Tax Policy. Clinton's tax increase was equal to 83 cents.

Republicans have been victims of this tactic as well. The Sierra Club accused Bush of having the “worst environmental record in U.S. history.” But “worst” by what measure? Even the Sierra Club admits that air got cleaner during Bush's tenure (nearly a 12 percent reduction in the six major pollutants between 2000 and 2005, according to official monitoring required by the Clean Air Act). And Bushâwhile certainly not as aggressive as the Sierra Club wantedâput in place much stricter controls on diesel emissions than had existed under his predecessor. In 2005, Bush also imposed the first federal controls on mercury emissions by power plants. We can't say who did have the “worst” record; but no president before Richard Nixon even had an Environmental Protection Agency, which was created in 1970.

Superlative claims can lead us to choose needlessly expensive products and make shallow political decisions. Approach them with care!

WARNING SIGN:

The “Pay You Tuesday” Con

B

Y NOW NEARLY EVERYBODY WHO HAS

I

NTERNET ACCESS IS PROBABLY

familiar with the Nigerian e-mail scams that have been going on since the 1980s. A supposedly wealthy or high-placed foreigner sends a message asking for financial helpâtodayâto move millions of dollars out of his homeland, in return for a percentage of the money to be paid later. That this is a con should be obvious, but the U.S. Secret Service was still warning in 2006 that the Nigerian e-mail scam “grosses hundreds of millions of dollars annually and the losses are continuing to escalate.”

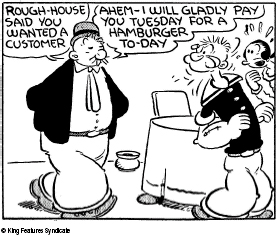

The warning sign is simple: if it sounds like J. Wellington Wimpy, it's likely to be a trick. Wimpy, a friend of Popeye, was an unscrupulous glutton who tried to snag a free meal with the classic line: “I will gladly pay you Tuesday for a hamburger today.” That “pay you Tuesday” element should raise suspicions.

In politics it's a little different but the principle is the same. We, the voters, are going to get our hamburger today. That is, we will if only we vote for the right candidate, who promises we won't have to pay until Tuesday, if ever. The difference is that Wimpy doesn't intend to pay, but we or our children will have to. In general, Democrats promise social programs without mentioning future costs to taxpayers, while Republicans promise reduced taxes but are vague about future deficits or program cuts.

Democrats constantly promise to “preserve Social Security” without mentioning that to finance the benefits scheduled in current law will require a sizable tax increase. Official projections issued in May 2006 put the shortfall at $4.6 trillion over the next seventy-five years. To put that in perspective, the shortfall amounts to more than a third of the entire U.S. economy for the year 2006. To be paid Tuesday, of course.

Bush, for his part, promised to “pay Tuesday” for the war in Iraq, for his tax cuts, and for big increases in domestic spending, including a prescription drug benefit that is the largest expansion of Medicare in its history. The president assured the nation in his 2002 State of the Union address: “Our budget will run a deficit that will be small and short-term”âbut as it turned out the deficit ballooned to $413 billion in 2004, a record measured in raw dollars and much above average even measured as a percentage of the economy. The deficit was still $318 billion the following year and an estimated $250 billion the next, and deficits of between $266 billion and $328 billion were projected each year for the remainder of the decade, according to the Congressional Budget Office. Those deficits are hardly “small” and certainly not “short-term,” as the president had predicted. When “Tuesday” arrives somebody is going to be stuck with a very large tab.

WARNING SIGN:

The Blame Game

T

O HEAR

P

RESIDENT

B

USH TALK, YOU WOULD THINK THAT GREEDY

lawyers are a major factor in the rising cost of health care. “One of the major cost drivers in the delivery of health care are [

sic

] these junk and frivolous lawsuits,” he said in 2004. He insisted that doctors ordering needless tests and procedures for fear of being sued were costing federal taxpayers “at least $28 billion a year” in added costs to government medical programs. This claim rested mainly on a single 1996 study suggesting that “defensive medicine” accounted for 5 percent to 9 percent of total spending on health care. However, that conclusion had been contradicted by just about every other researcher who had looked at the problem.

The basis of Bush's blame-the-lawyers claim was disputed by both the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) and the Government Accountability Office (GAO), respected and politically neutral investigative agencies. After examining all the research on the subject, the CBO found “no evidence” that caps on damage awards of the sort Bush sought would reduce medical spending. “In short, the evidence available to date does not make a strong case that restricting malpractice liability would have a significant effect, either positive or negative, on economic efficiency,” the CBO said.

Bush was engaging in the blame game, pointing a finger at an unpopular group and hoping to divert attention from the weakness of his own evidence. People who find their own position weak or indefensible often attack. That's why we say casting blame is a clue that the attacker may need a closer look than the person being blamed.

Blaming often occurs reflexively, out of pure partisanship and with little regard for facts. For example, a former Clinton aide, Sidney Blumenthal, suggested that George W. Bush was to blame for the flooding in New Orleans brought about by Hurricane Katrina in 2005. In a widely quoted article for Salon.com, Blumenthal wrote that “the damage wrought by the hurricane may not entirely be the result of an act of nature.” He cited budget cuts by the Bush administration in flood-control projects in Louisiana. As later investigation revealed, however, the major cause of the flooding was the collapse of floodwalls and levees built before Bush took office. An engineering study commissioned by the National Science Foundation concluded that money was not the problem: “The performance of many of the levees and floodwalls could have been significantly improved, and some of the failures likely prevented, with relatively inexpensive modifications of the levee and floodwall system details.” The report's author, Raymond Seed of the University of CaliforniaâBerkeley, told reporters there was a “high likelihood” that human error was to blame, and possibly outright malfeasance: “Some of the sections may not have been constructed as they were designed.” All this was underscored in June 2006 when the Army Corps of Engineers released a nine-volume study of the disaster, saying the New Orleans flood-control system failed to work as it was supposed to, and had so many weaknesses it had been “a system in name only.” Whatever blame history will place on Bush's shoulders for his slow response to the flooding, Blumenthal was simply wrong to blame the president for the flooding itself.

Politicians' tendency to point fingers was epitomized by a T-shirt slogan we spotted: “When in doubtâblame liberals!” The word “conservatives” could fit just as well. Liberals like to blame “big oil companies” when gasoline prices shoot up, ignoring such factors as clean-air regulations that create local supply bottlenecks, or the surging global appetite for crude oil as China and other countries industrialize. Conservatives typically blame liberals for being “soft on crime,” ignoring the steady rise in the U.S. prison population, to a point where as of mid-2005 nearly one in every 200 U.S. residents is serving time in a federal, state, or local lockup. And of course, whatever party is out of power always blames the incumbent president when the economy goes soft or the stock market tanks, even though the White House has only modest influence on global economic trends and markets.

When you hear people casting blame, take a close look at their facts. It's good to say to yourself, “That sounds like a one-sided case for the prosecution. What would the defense have to say about it?”

WARNING SIGN:

Glittering Generalities

B

EWARE OF ATTRACTIVE-SOUNDING BUT VAGUE TERMSâWHAT STUDENTS

of propaganda techniques call glittering generalities. Coca-Cola isn't just carbonated water that's been flavored and sweetened, it's “the Real Thing.” United isn't just an airline emerging from bankruptcy, it's your access to “the friendly skies.” Allstate isn't just a colossal insurance company, it's “good hands.” The U.S. Army isn't just a military organization, it's the “path of strength.” The idea is to get you to buy the product without asking too many questions.

Perhaps the most popular glittering generality among politicians is that of mouthing support for the “middle class.” In politics, it's hard to find a candidate who isn't for the middle class, because in America so few people think of themselves as lower-class or upper-class. In 2004, Democrat Dick Gephardt promised in his TV ads to “fight for America's middle class.” John Edwards promised to “target tax cuts to the middle class.” Howard Dean said he'd “strive for greater tax fairness for middle-class working families.” Kerry said he “won't raise taxes on the middle class.” And the president, not to be out-glittered, said “the middle class is paying less in federal taxes” because of his tax cuts.