unSpun (6 page)

John Kerry used the same tactic late in his 2004 campaign, running an ad saying “Bush has a plan to cut Social Security benefits by 30 to 45 percent.” That was simply false. Bush had stated repeatedly there would be no changes in benefits for anyone already getting them. What Kerry was referring to was a proposal, which Bush eventually embraced, to hold future benefit levels even with the rate of inflation, rather than allowing them to grow more quickly, in line with incomes. Over a very long period of time, that would mean benefit levels perhaps 45 percent lower than they would have been under current benefit formulas (assuming, for the sake of argument, that Congress enacted the tax increases necessary to finance those). But most of the future retirees who might experience that 45 percent “cut” were still unborn at the time Kerry ran the ad.

When you hear a politician talking about a “cut” in a program he or she favors, ask yourself, “A cut compared to

what

?”

TRICK #7:

The Literally True Falsehood

S

OMETIMES PEOPLE PICK WORDS THAT ARE DECEPTIVE WITHOUT

being strictly, technically false. President Clinton, who had an affair with one of his female interns, didn't object when his lawyer told a judge that the intern had filed an affidavit saying “there is absolutely no sex of any kind in any manner, shape or form, with President Clinton.” Clinton later said that statement was “absolutely” true. How could he endorse the statement that “there is absolutely no sex of any kind,” given the shenanigans that actually went on? In his grand jury testimony of August 17, 1998, Clinton offered this famous explanation:

PRESIDENT CLINTON: It depends on what the meaning of the word “is” isâ¦. If “is” means is and never has been that is notâthat is one thing. If it means there is none, that was a completely true statement.

In other words, there had been sex, but not at the moment when the statement was made in court. Clinton went too far: U.S. District Judge Susan Webber Wright later found Clinton in civil contempt for giving “intentionally false” testimony. (He also denied having “sexual relations” with Lewinsky.) His license to practice law in Arkansas was suspended for five years and he was fined $25,000. He also gave up his right to appear as a lawyer before the U.S. Supreme Court rather than face disbarment proceedings there. But even though redefining “is” didn't work for Clinton, his remark shows us how clever deceivers can try to mislead us withoutâin their minds, at leastâactually lying.

“Reduced fat” may be a literally true claim, but it doesn't mean “low fat,” just less fat than the product used to have. “Unsurpassed” doesn't mean “best”; it is just a claim that the product is as good as any other. “Nothing better” might also be stated as “as good but no better.” And the claim that a product is “new and improved” doesn't signify that it is any good. What advertisers are trying to say is “Give us another tryâwe think we've got it right this time.”

The Stouffer's Food Corp. made a literally true but misleading claim about its Lean Cuisine frozen entrées in 1991, in a $3 million advertising campaign that said: “Some things we skimp on: Calories. Fat. Sodiumâ¦always less than 1 gram of sodium per entrée.” One gram of sodium is quite a lot. Dietary sodium is usually measured in milligramsâthousandths of a gramâand Lean Cuisine entrées contained about 850 milligrams. That's about a third of the FDA's recommended total intake for a full day, and too much to be called “low sodium” under public guidelines. The Federal Trade Commission ordered Stouffer's to stop making the claim. Whether or not it was literally true, the FTC concluded, “the ads were likely, through their words or images, to communicate a false low-sodium claim.”

KFC Corporation used the same sort of “literally true falsehood” in an attempt to palm off fried chicken as health food. One of its ads showed a woman putting a bucket of KFC fried chicken down in front of her husband and saying, “Remember how we talked about eating better? Well, it starts today!” The narrator then said, “The secret's out: two Original Recipe chicken breasts have less fat than a BK Whopper.”

That was literally true, but barely. The fried chicken breasts had 38 grams of total fat, just slightly less than the 43 grams in a Burger King Whopper. However, the chicken breasts also had three times more cholesterol (290 milligrams versus 85 milligrams), more than twice as much sodium (2,300 milligrams versus 980 milligrams), and slightly more calories (760 versus 710), according to the Federal Trade Commission. Not to mention that saying that something has less fat than a Whopper is like calling a plot of ground less polluted than your local landfill. The FTC charged KFC with false advertising, and KFC settled by agreeing to stop claiming that its fried chicken is better for health than a Burger King Whopper.

And of course, Clinton isn't the only politician to tell a literally true falsehood. In 1975, the former CIA director Richard Helms told reporters, “So far as I know, the CIA was never responsible for assassinating any foreign leader.” That was true, but Helms didn't mention that the CIA had

attempted

assassinations of Fidel Castro and a few other foreign leaders. As the then CBS reporter Dan Schorr later noted, “It turned out as Helms said, that no foreign leader was directly killed by the CIA. But it wasn't for want of trying.” Another example: In 1987 interviews, then Vice President George H. W. Bush told reporters that he was “out of the loop” about the arms-for-hostages trade known as Iran Contra. Most of us would interpret “out of the loop” as “Nobody told me.” Bush once said in passing to CBS's Dan Rather that he had a different definition: “No operational role.” A careful listener might have caught that Bush was denying only that he was running the operation, not denying that he knew of it or approved of it. Sure enough, years later a special prosecutor made public a diary entry by Caspar Weinberger, who was the U.S. secretary of defense at the time, saying that Bush was among those who approved a deal to gain release of five hostages being held by Iran in return for the sale of 4,000 wire-guided antitank missiles to Iran via Israel.

When you hear vague phrases or carefully worded claims, always ask, “Are they really saying what I think they're saying? What do those words mean, exactly? And what might they be leaving out?”

TRICK #8:

The Implied Falsehood

W

HEN THE

U

NITED

S

TATES WENT TO WAR AGAINST

I

RAQ IN 2003,

most Americans believed that Saddam Hussein had something to do with the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. And after the 2004 election, most Americans had the impression that President Bush had told them as much. The National Annenberg Election Survey's postelection poll found that 67 percent of adults found the following statement to be truthful: “George W. Bush said that Saddam Hussein was involved in the September 11 attacks.” Only 27 percent found it untruthful.

In fact, Bush never said in public (or anywhere else that we know of) that Saddam was involved in the 9/11 attacks. The CIA didn't believe Saddam was involved, and no credible evidence has ever surfaced to support the idea. “We have never been able to prove that there was a connection there on 9/11,” Vice President Dick Cheney said in a CNBC interview in June 2004. But he also said he still thought it possible that an Iraqi intelligence official had met lead hijacker Mohamed Atta in the Czech Republic in April 2001, despite a finding to the contrary by the independent 9/11 Commission. “We've never been able to confirm or to knock it down,” Cheney said. To many ears, Cheney was saying he believed there

was

a connection, and that he lacked only the proof. In fact, after an exhaustive effort to confirm the meeting, U.S. intelligence agencies had found no credible evidence.

Advertisers often try to imply what they can't legally say. One marketer sold a product he called the Ab Force belt, which caused electrically stimulated muscle twitches around the belly. The Federal Trade Commission cracked down on similar products that overtly claimed that their electronic muscle stimulation devices would cause users to lose fat, reduce their belly size by inches, and create well-defined, “washboard” or “sixpack” abdominal muscles without exercising. In some of the most frequently aired infomercials on national cable channels in late 2001 and early 2002, sellers made claims including, “Now you can get rock hard abs with no sweatâ¦. Lose 4 Inches in 30 Days Guaranteedâ¦. 10 Minutes =600 Sit-Ups.” Launching what it called “Project AbSurd,” the FTC got those blatantly false claims off TV and got the marketers to agree to pay $5 million. (They had sold $83 million worth of belts, the FTC said.)

But the Ab Force marketer persisted. He said his own advertising never made

specific

claimsâwhich was true: it just showed images of well-muscled, bare-chested men and lean, shapely women, with close-ups of their trim waists and well-defined abdominals. And, of course, he had named his device Ab Force. The case went to a hearing at the FTC, where regulators presented some convincing evidence of how an unstated message can still get across. The Ab Force ads were shown to groups of consumers, 58 percent of whom later said the ads were telling them that the belt would cause users to lose inches around the waist, while 65 percent said they got the message that the product would give users well-defined abdominal muscles. The FTC's administrative law judge ruled that the unstated message implied by the ad, combined with the Ab Force name, constituted false advertising.

When the full commission voted unanimously to uphold the judge's order, it said the marketer had managed to sell $19 million of his belts even though his ads made no specific claim. “It illustrates how false and unsubstantiated claims can be communicated indirectly but with utter clarityâto the detriment of consumers and in violation of the laws this Commission enforces,” the FTC's decision stated.

When you see or hear something being strongly implied but not stated outright, ask yourself, “Why do they have to lay it between the lines like that? Why don't they just come out and say it?” Often there's a very good reason: what the speaker wants you to believe isn't true.

Chapter 4

UFO Cults and Us

Why We Get Spun

A man with a conviction is a hard man to change. Tell him you disagree and he turns away. Show him facts or figures and he questions your sources. Appeal to logic and he fails to see your point.

âL

EON

F

ESTINGER

, et al.,

When Prophecy Fails

(1956)

H

AVE YOU EVER WONDERED WHY OTHER PEOPLE ARE SO UNREASONABLE

and hard to convince? Why is it that they disregard hard facts that prove you're right and they're wrong? The fact is, we humans aren't wired to think very rationally. That's been confirmed recently by brain scans, but our irrational reaction to hard evidence has been the subject of scholarly study for some time. Consider one of the most famous scientific observations in all of psychology, the story of a UFO cult that was infiltrated by the social psychologist Leon Festinger and his colleagues half a century ago.

They observed a small group of true believers whose leader was a woman the authors called Marian Keech, in a place they called Lake City. Mrs. Keech said she had received messages from beings called Guardians on Planet Clarion saying that North America would be destroyed by a flood, but that her followers would be taken to safety on a UFO a few hours earlier, at midnight on December 21, 1954. Members of her cult quit jobs, sold possessions, dropped out of school, and prepared for the space journey by removing metal objects from their clothing as instructed by Mrs. Keech. They gathered in her living room on the appointed night, and waited.

Midnight came and went, and of course neither the flood nor the promised spacecraft arrived. But did the faithful look at this incontrovertible evidence and conclude, “Oh, well, we were wrong?” Not a chance. At 4:45

A.M

., as morning approached, Mrs. Keech told them that she had received another message: the cataclysm had been called off because of the believers' devotion. “Not since the beginning of time upon this Earth,” she said, “has there been such a force of Good and light as now floods this room.” And then she told the group to go spread the word of this miracle. One member walked out, fed up with Keech's failed predictions, but the others were jubilant. In the days that followed, Festinger and his colleagues reported, cult members who previously had shown no interest in proselytizing now put their energies into gaining converts. They became even more committed to their cause after seeing what any reasonable person would conclude was shattering proof that they had been completely wrong.

Why should this be? The reason, Festinger tells us, is that it is psychologically painful to be confronted with information that contradicts what we believe. For Mrs. Keech's followers to concede error would have meant admitting they had been colossal fools. But convincing others of their beliefs would not only avoid any such embarrassment, it would provide some false comfort, as though more believers would constitute more proof.

The Keech cult is an extreme case, but the discomfort at being confronted with evidence of error is a universal human emotion. It's just no fun to admit we've been wrong. So we strive to avoid that unpleasant feeling of psychological conflictâwhat Festinger calls cognitive dissonanceâthat occurs when deeply held beliefs are challenged by conflicting evidence. Keech's followers could have reduced their dissonance by abandoning their religious beliefs, but instead some of them adopted an explanation of the new evidence that was compatible with what they already believed. Cognitive dissonance is a fancy term for something all of us feel from time to time. Decades of social science experiments have shown that, in a sense, there's a little UFO cultist in everybody.

The Moonbat Effect

A more recent example took place in 2006 when a website called truthout.org reported the political equivalent of a UFO landing that didn't happen. On Saturday, May 13, the truthout contributor Jason Leopold reported that President Bush's top political adviser, Karl Rove, had been indicted for perjury and lying to investigators in a CIA leak investigation, that Rove's lawyer had been served with the indictment papers during a fifteen-hour meeting at his law offices the previous day, and that the prosecutor would announce the charges publicly within a week. All this was reported as fact, without any “maybes” or qualifications.

The news was celebrated by followers of truthout, a liberal, anti-Bush site. One commenter on the website's “Town Meeting” message board even suggested a war crimes trial, saying “How about sending him and his bosses to The Hague?” Another gloated, “All that needs to be done now is to send him to the crossbar hotel, under the loving care of Bubba & No-Neck.” The fact that no major news organization was reporting the Rove indictment was brushed off as evidence of the supposed pro-Bush, antiliberal bias of the “MSM” or mainstream media.

But the story quickly drew strong denials. Rove's lawyer said he, the lawyer, was out of his office that day taking his sick cat to the veterinarian and certainly hadn't been served with an indictment. Days passed with no indictment announced, and on Thursday truthout's executive director, Marc Ash, said that “additional sources have now come forward and offered corroboration to us.” At the end of the week in which the indictment was supposed to be announced, Ash issued a “partial apology,” but only about the timing: “We erred in getting too far out in front of the news-cycle.” He kept the original story on the website. On May 25 Ash wrote, “We have now three independent sources confirming that attorneys for Karl Rove were handed an indictment.” On June 3 he wrote, “We stand by the story.” And still no indictment.

A number of readers expressed disappointment but others seemed to cling even more firmly to their now discredited editor and reporter's story. “Mr. Leopold's version may have been perfectly correct but changed by subsequent events he was not privy to,” wrote one, posting a comment on truthout's “Town Meeting” message board. Another wrote, “No apology needed. I am glad you took the risk and you confirmed my faith in you.” Still another wrote, “Persevere, keep the faith and above all keep up the good work. You can expect my contribution next week.” Even when Rove's lawyer finally announced on June 13 that the special prosecutor had informed him that Rove wasn't going to be indicted, a diehard few continued to believe truthout. “I know that I trust their word over what the media says,” one supporter wrote. Ash still kept the indictment story on the website and said of Rove's lawyer, “We question his motives.”

However, by this time most of the comments on the “Town Meeting” board reflected a view of reporter Leopold and editor Ash as doggedly self-deceived, or worse. One wrote, “I've been on your side all along and am a great believer in TO [truthout], but this borders on lunacy.” And another said, “There's probably a 12 step program out there for this affliction. You believe, with all your heart, soul, mind and body that a story is correct. You base your belief, not on evidence, logic or reason, but simply because you want to believe so badly, the thought of it being wrong invalidates your very existence and that makes your head hurt.” That didn't please truthout's proprietors, who removed the comment. But it describes the effects of cognitive dissonance pretty well.

Extreme political partisans sometimes display such irrational thinking that they have come to be dismissed as “barking moonbats.” A barking moonbat is “someone who sacrifices sanity for the sake of consistency,” according to the London blogger Adriana Cronin-Lukas of Samizdata.net, who helped popularize the colorful phrase. It is most often applied derisively to extreme partisans on the left, but we use it as originally intended, to apply to all farout cases whose beliefs make them oblivious to facts, regardless of party or ideology.

The Psychology of Deception

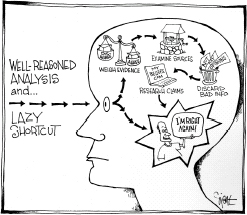

In the past half century, the science of psychology has taught us a lot about how and why we get things wrong. As we'll see, our minds betray us not only when it comes to politics, but in all sorts of matters, from how we see a sporting event, or even a war, to the way we process a sales pitch. Humans are not by nature the fact-driven, rational beings we like to think we are. We get the facts wrong more often than we think we do. And we do so in predictable ways: we engage in wishful thinking. We embrace information that supports our beliefs and reject evidence that challenges them. Our minds tend to take shortcuts, which require some effort to avoid. Only a few of us go to moonbat extremes, but more often than most of us would imagine, the human mind operates in ways that defy logic.

Psychological experiments have shown, for one thing, that humans tend to seek out even weak evidence to support their existing beliefs, and to ignore evidence that undercuts those beliefs. In the process, we apply stringent tests to evidence we don't want to hear, while letting slide uncritically into our minds any information that suits our needs. Psychology also tells us that we rarely work through reasons and evidence in a systematic way, weighing information carefully and suspending the impulse to draw conclusions. Instead, much of the time we use mental shortcuts or rules of thumb that save us mental effort. These habits often work reasonably well, but they also can lead us to conclusions we might dismiss if we applied more thought.

Another common psychological trap is that we tend to overgeneralize from vivid, dramatic single examples. News of a terrible airline crash makes us think of commercial flying as dangerous; we forget that more than 10 million airline passenger flights land safely every year in the United States alone. Overhyped coverage of a few dramatic crimes on the local news makes us leap to the conclusion that crime is rampant, even when a look at some hard statistics would convince us that the violent crime rate in 2005 (despite a small increase that year) was actually 38 percent

lower

than its peak in 1991.

Psychologists have also found that when we feel most strongly that we are right, we may in fact be wrong. And they have found that people making an argument or a supposedly factual claim can manipulate us by the words they choose and the way they present their case. We can't avoid letting language do our thinking for us, but we can become more aware of how and when language is steering us toward a conclusion that, upon reflection, we might choose to reject. In this chapter we'll describe ways in which we get spun, and how to avoid the psychological pitfalls that lead us to ignore facts or believe bad information.

And this has nothing to do with intelligence. Presidents, poets, and even professors and journalists fall into these traps. You do it. We all do it. But we are less likely to do it if we learn to recognize how our minds can trick us, and learn to step around the mental snares nature has set for us. The late Amos Tversky, a psychologist who pioneered the study of decision errors in the 1970s, frequently said, “Whenever there is a simple error that most laymen fall for, there is always a slightly more sophisticated version of the same problem that experts fall for.”

*1

Experts such as the doctors, lawyers, and college professors who made up a group convened in 1988 by Kathleen Jamieson to study the impact of political ads. They all thought other people were being fooled by advertising, but that they themselves were not. They were asked, “What effect, if any, do you think the presidential ads are having on voters in general and us in particular?” Every person in the group said that voters were being manipulated. But each one also insisted that he or she was invulnerable to persuasion by ads. Then the discussion moved on to the question “What ads have you seen in the past week?” One participant recounted that he had seen an ad on Democratic presidential candidate Michael Dukakis's “revolving-door prison policy.” The group then spent time talking about Dukakis's policies on crime control, and in that discussion each adopted the language used in the Republican ad. The ad's language had begun to do their thinking about Dukakis for them. Without being aware of it, they had absorbed and embraced the metaphor that Dukakis had installed a “revolving door” on state prisons. The notion that others will be affected by exposure to messages while we are immune is called the third-person effect.

The other side of the third-person effect is wishful thinking. Why do most people think they are more likely than they actually are to live past eighty? Why do most believe that they are better than average drivers? At times we all seem to live in Garrison Keillor's fictional Lake Wobegon, where “all the children are above average.” To put it differently: in some matters we are unrealistic about how unrealistic we actually are.

The “Pictures in Our Heads” Trap

Misinformation is easy to accept if it reinforces what we already believe. The journalist Walter Lippman observed in 1922 that we are all captives of the “pictures in our heads,” which don't always conform to the real world. “The way in which the world is imagined determines at any particular moment what men will do,” Lippman wrote in his book

Public Opinion.

Deceivers are aware of the human tendency to think in terms of stereotypes, and they exploit it.

A good example of this is the way the Bush campaign in 2004 got away with falsely accusing John Kerry of repeatedly trying to raise gasoline taxes and of favoring a 50-cent increase at a time when fuel prices were soaring. A typical ad said, “He supported higher gasoline taxes eleven times.” In fact, Kerry had voted for a single 4.3-cent increase, in 1993. The following year, he flirted briefly in a newspaper interview with the idea of a 50-cent-a-gallon gasoline tax, but quickly dropped the notion and never mentioned it again. Nevertheless, most voters swallowed the Republican falsehood without a hiccup.

Democrats exploit this psychological trap, too. In the previous chapter we noted how Kerry had falsely accused Bush of favoring big “cuts” in Social Security benefits. That was also widely believed. In the National Annenberg Election Survey, nearly half of respondentsâ49 percentâtended to believe a statement that Bush's plan would “cut Social Security benefits 30 to 45 percent.” Only 37 percent found the statement untruthful. And we want to stress an important point here: the public wasn't thinking of a “cut” as a slowdown in the growth of benefits for those retiring decades in the future; they were thinking of a real cut. The Annenberg survey found that 50 percent rated as truthful a statement that “Bush's plan to cut Social Security would cut benefits for those currently receiving them,” and only 43 percent found the statement untruthful.

Bush, of course, had stated repeatedly during his 2000 campaign and throughout his first term that he would not cut current benefits by a penny. So why would a plurality of the public believe the opposite? The reason, we believe, is that Social Security is thought of as a Democratic program and Republicans are thought of as opposing it (somewhat unfairly: large majorities of Republican House and Senate members voted for it when it was passed in 1935). Because of the stereotyped view that Republicans don't favor Social Security, too few took the trouble to question the idea that Bush would cut current benefits.

It is difficult for candidates to overcome these stereotypes. In 1990, voters in Pennsylvania were disposed to believe that the Republican nominee, Barbara Hafer, opposed abortion rights and that the incumbent Democratic governor, Robert Casey, favored a legal right to abortion; the reverse was true. In general, Democrats are more likely to be “pro-choice” and Republicans “pro-life,” but not in this case. A good rule is that “in general” doesn't necessarily apply to “this specific.”

Sometimes we have to avoid mental shortcuts and take the long way around if we want to avoid being manipulated or making these mistakes on our own. Ask yourself: “Is the picture in my head a good likeness of reality? Does this Democrat in fact favor this tax increase? Does this Republican in fact want to cut Social Security benefits? Where's the evidence?”