unSpun (12 page)

Non-Evidence: Linus Pauling and Bruce Willis

We've shown that anecdotes can mislead us, and that sloppy, biased, or made-up studies can masquerade as evidence, and that even good studies can fail to hold up when set beside later research. Here are a few other things that do not count as evidence.

A

PPEALS TO

A

UTHORITY

Linus Pauling won two Nobel Prizes, one for chemistry and the other for peace, but he had no particular expertise in medicine. Nevertheless, millions of people swallowed his claims that high doses of vitamin C could cut the incidence of the common cold and might even be effective against cancer. In fact, at least sixteen controlled experiments, some involving thousands of volunteers, have failed to show that vitamin C has any effect on either condition. Dr. Stephen Barrett of Quackwatch.org reports that “no responsible medical or nutrition scientists share [Pauling's] views.”

FactCheck.org's Guide to Testing Evidence

At FactCheck.org, we find ourselves asking a few basic questions again and again in evaluating evidence. Here's a short list of tests we have found useful:

⢠Is the source highly regarded and widely accepted? There are a number of longstanding organizations we know we can count on for reliable, unbiased information. For job statistics, the Bureau of Labor Statistics is every economist's basic source. For hurricane statistics, the National Hurricane Center is considered the authority. For determining when business recessions begin and end, the private, nonprofit National Bureau of Economic Research is an authority cited in economic history books. And for abortion statistics, the Guttmacher Institute is accepted by all sides as trustworthy.

⢠Is the source an advocate? Claims made by political parties, candidates, lobbying groups, salesmen, and other advocates may be true but are usually self-serving and as a result may be misleading; they require special scrutiny. Always compare their information with other sources. The National Research Councilâchartered by Congress and able to call on the nation's most eminent expertsâis a better source on whether gun-control laws cut crime than is a group devoted to lobbying for or against such laws. The Guttmacher Institute does advocate “reproductive freedom,” but we accept its numbers not only because the institute is trusted by both sides of the debate, but also because in this case they support a president who is on the other side of the issue. The institute's report that the number of abortions continues to diminish under Bush is the opposite of what we would expect if it were allowing ideological bias to color its findings.

⢠What is the source's track record? Look for previous experience. In our abortion example, Stassen had no record of conducting studies on abortion statistics. In contrast, the Guttmacher Institute's surveys of abortion providers go back to 1973.

⢠What method is used? Mitch Snyder's estimate of the number of homeless people turned out to depend on a collection of guesses, at best. The Urban Institute's estimates, though they also involve some assumptions and guesswork, are based on U.S. Census data gathered in a uniform way from a very large, random sample.

⢠Does the source “show its work”? Good researchers always explain how they arrived at their numbers and conclusions. Daniel Cristol described exactly how he and his colleagues conducted their 400 timed observations of crows, and he published the results. Good research methods are transparent.

⢠Is the sample random? News organizations and websites are fond of conducting “unscientific” polls. Viewers or visitors are asked to express a preference, and the results are reported. This is just a marketing method designed to draw interest; the results are utterly meaningless because the sample is self-selected, not random. Some such polls have even been intentionally rigged. At best, they are like Stassen's nonrandom sixteen-state sample, which turned out not to reflect the situation in all fifty states.

⢠Is there a control group? Good scientific procedure requires a “control” to provide a valid basis for comparison. A crow dropping nuts in front of a car proves nothing. Cristol watched crows when cars were coming, but he also watched crows when cars were notcoming, and he observed the difference (none). In tests of new drugs one group gets a placebo, with no active ingredients, to provide a point of comparison with the group that gets the actual drug.

⢠Does the source have the requisite skill? A trained epidemiologist should be trusted more than a newspaper headline writer to evaluate whether a cluster of cancer cases was caused by something in the water, or was just a statistical fluke.

⢠Have the results been replicated, or contradicted? Sometimes one study tells a story that isn't backed up by later research. Have the results been repeated in similar studies? Do other researchers agree, or do they come up with contrary findings? The Cold-Eeze story shows how cherry-picked studies can mislead us.

Â

The lesson here is that somebody who is an authority in one field isn't necessarily qualified in another. Sam Waterston plays a smart, tough prosecutor on television's

Law & Order

series, but so far as we know he has no special expertise as a financial adviser. So why should we give any special weight to his TV commercials praising the brokerage firm TD Waterhouse? Bruce Willis endorsed President George H. W. Bush in 1992 and supported the current war in Iraq, but his portrayal of action heroes on the screen is no reason to give his political or military views any more weight than your next-door neighbor's. The same goes for Martin Sheen's endorsement of Howard Dean in the 2004 Democratic presidential primary. Playing a president on TV is about as valid a qualification for making political judgments as playing a doctor on TV might be in recommending decaffeinated coffee, the way Robert Young did in the 1970s, after starring in

Marcus Welby, MD

on television.

Before relying on any authority, ask yourself, “Is this source competent? Does he know what he's talking about? Does she have any real evidence? Do other authorities in the same field agree?”

A

PPEALS TO

P

OPULARITY

Advertisers use these all the time. A typical example: a hospital in Saginaw, Michigan, says it is “preferred two to one.” Does having a large number of patients mean that a hospital provides the best care? Not necessarily. It might simply have better parking or be located more conveniently.

Other examples to look out for: “top-selling”; “number one”; “preferred over⦔ In politics the “front runner” is often the candidate to watch, but is not necessarily the best one or even the one destined to win, as onetime front runner Howard Dean discovered in the 2004 Democratic primary races. And in February 2006, both Ford and General Motors were claiming to be the top-selling brand of automobiles in the United States, as figures on 2005 vehicle registrations trickled in. In fact, both automakers had been losing ground for years, falling from a combined 60 percent of the U.S. market in 1986 to about 45 percent in 2005. Each might just as easily have said it was “preferred by fewer and fewer.”

Popularity may settle elections, but it doesn't settle questions of fact. Ask yourself, “Is this thing popular because it's good, or for some other reason, such as a big advertising budget?”

F

AULTY

L

OGIC

Whole books and several websites have been devoted to the question of logical fallacies. One that trips up many people is the idea that when two events happen, the first one has caused the second. In Latin, this is called the

post hoc, ergo propter hoc

fallacy, meaning “after this, therefore because of this.”

The

post hoc

fallacy is seductive because of what we observe to be true in our daily lives. We step on the car's accelerator; the car moves forward. We flip on a light switch; the light comes on. We touch a lit match to kindling; the kindling catches fire. We may be disappointed, however, if we assume that the shirt we put on before a successful fishing trip is therefore a “lucky” shirt that will magically produce fish the next time. That's just superstition. When we fall prey to the

post hoc

fallacy, we're like the rooster who thought his crowing made the sun rise.

Consider a statement being made in early 2006 by the Brady Campaign, formerly known as Handgun Control, Inc. The campaign stated that passage of the Brady Law in 1993 (imposing background checks for handgun purchasers) and the federal “assault weapons” ban in 1994 (which banned the sale of certain semi-automatic weapons) were followed by years of declines in violent crime. This the group cited as proof that “gun laws work.”

It's true that crime rates plunged throughout the 1990s, starting just about the time the two gun laws were enacted. But that doesn't mean that the gun laws

caused

the decline. Criminologists, economists, and just about everybody else are still debating over what did. Proposed causes include increased numbers of police, the practice of “community policing,” “zero-tolerance” policies, and even the legalization of abortion two decades earlier. In late 2004, the Committee on Law and Justice of the National Research Council examined the question whether gun laws affect crime rates, and concluded that a connection couldn't be shown: “In summary, the committee concludes that existing research studies and dataâ¦do not credibly demonstrate a causal relationship between the ownership of firearms and the causes or prevention of criminal violence or suicide.”

Be careful about jumping to conclusions. Always ask, “Are these facts really connected?”

Andâalwaysâkeep asking, “What's the evidence?”

Chapter 7

Osama, Ollie, and Al

The Internet Solution

S

O FAR WE'VE POINTED OUT HOW TO RECOGNIZE SPIN AND MISINFORMATION

, explained some of the tricks that spinners use to mislead us, and described the psychological traps that too often make us accomplices in our own deception. We've said that staying unspun can save us money, embarrassment, and perhaps even our lives, but that it also requires us to adjust our mental habits so that we look actively for facts that might

disprove

whatever we happen to believe at the moment, rather than giving in to our hardwired human tendency to see only supporting evidence. And we've discussed the basics of how to tell good evidence from random anecdotes. Now it's time to talk about where, and how, to find the solid facts you need.

The solution to spin is the Internet, if you use it very carefully.

The Wall Street Journal

's personal-technology columnist, Walt Mossberg, may have put it best: “The World Wide Web is a marvelous thing. Because it exists, more people have direct access to more knowledge than at any time in history.” That's trueâand there's more reliable information being added every day. Furthermore, much of this information is available to everyone, for only the price of an Internet connection.

Unfortunately, as you probably know, the Web is also a conduit for new gushers of toxic informational sludge as well. Anybody can say anything they want on the Internet, regardless of whether it is true, and people can post anonymously or under a false identity. We've already mentioned websites that tout fraudulent products, and con artists who use mass e-mailings to reach their victims. The trick is to sort the gold from the dross. We'll show you how to do that, and perhaps even have some fun along the way.

To illustrate, we offer the story of an Internet hoax that was swallowed by untold thousands of gullible believersâand we show how to find the facts.

Osama, Ollie, and Al

Within weeks after the calamity of September 11, 2001, an e-mail began to circulate containing what the anonymous author described as “stunning” information. He (or she) claimed that Oliver North had warned Congress as far back as 1987 that Osama bin Laden is “the most evil man alive” and had said, “I would recommend that an assassin team be formed to eliminate him and his men from the face of the earth.” Furthermore, this message stated, the senator questioning North was Albert Gore of Tennessee, the future vice president and Democratic candidate for president.

This message was red meat to a lot of conservatives. At a time when President Bush was being criticized for ignoring warnings of a possible terrorist attack, the idea that Al Gore could have prevented 9/11 if only he had listened to a former Ronald Reagan aide was irresistible. The message was forwarded and reforwarded countless times.

The message referred to North's televised testimony before a Senate committee investigating the Iran-Contra affair. North, now a conservative political commentator, was then a lieutenant colonel in the U.S. Marine Corps and had played a key role in the scandal as a White House military aide involved in secretly aiding the Contra rebels of Nicaragua in their attempt to overthrow the leftist president of Nicaragua, Daniel Ortega. But the message was totally false. In 1987, bin Laden was in Afghanistan fighting the Soviet Union, not the United States. He didn't form al Qaeda until the following year. Gore didn't question North: he wasn't even a member of the Iran-Contra investigating committee. The man questioning North was John Nields, the investigating committee's lawyer. The security system cost $13,800 (according to North's subsequent indictment) and not $60,000.

Yet this nonsense still circulates. Our inbox at FactCheck.org contains messages from dozens of people who have received the hoax, asking us whether there is anything to it. A woman who said she lives just blocks from the site of the World Trade Center called us in January 2006 after her brother sent her a version of the message complete with color photos of the Twin Towers burning. She said that despite her expressions of skepticism, her brother insisted it was true. There were plenty of reasons for the sister to question the message. Why isn't North himself hammering away at it constantly on Fox News, where he is host of a weekly program? Would Al Gore really have asked softball questions such as “Why are you so afraid of this man?” at a nationally televised hearing?

The brother swallowed this bunkum, we suspect, because he wanted to believe it. The Ollie-Osama-Al fairy tale made liberal Democrats look like fools and the hard-nosed conservative North look like a prophet. It also shifted blame for the failure to foresee the 9/11 attacks away from incumbent President George W. Bush. While we can't read the brother's mind, he probably fell into the “root for my side” trap we described in Chapter 4. What's certain is that he failed to adopt the active open-mindedness that could have saved him from being fooled. We know this because he not only failed to note the warning signs that made his sister doubt this tale, he also failed to make even a feeble effort to look for contrary evidence. And he could have found that evidence with no more effort than it took him to forward the fable to his sister.

What Ollie Really Said

As we write this, an Internet search for the keywords “Oliver North” plus “bin Laden” brings up literally dozens of articles disputing the hoax. That would have told our correspondent's brother that, at the very least, there were serious doubts about the accuracy of the story, and that a little more research was called for. The very first hit on our search was an article headlined “Oliver Twisted,” which flatly declares that the story of the hearing is false.

Why should we believe this article and not an e-mail message, which may have come from a trusted friend or relative? Actually, we shouldn't believe either of them, not automatically. So far we've discovered only that the e-mail

may

be a hoax and that we need to dig more deeply.

First, we evaluate the “Oliver Twisted” article. It gives the sources of its information in footnotes, thus enabling us to check what's being said. Also, the article appears on Snopes.com, a website that has been around for years and is run by two California folklore experts, Barbara and David P. Mikkelson, who are devoted to examining the many urban legends that have migrated to the Web. That's another point in favor of Snopes.com, a site that isn't pushing any particular political agenda or point of view. As we look farther down our search list, we also find that half a dozen similar websites, all of them devoted to debunking false Internet rumors, are also calling the Ollie-Osama-Al story false. So far, the neutral bunk-busters are unanimous: this is a scam.

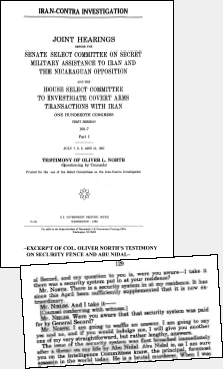

And the final proof is also right there on the Internet. Midway down the first page of our search results, we find a link to the U.S. Senate, which has devoted a brief article to exposing this very hoax. Better yet, the Senate staff has posted a copy of the actual transcript of the 1987 hearings into the Iran-Contra affair at which North gave his testimony. Gore wasn't there. Committee lawyer Nields did the questioning. North named Abu Nidal, not bin Laden. Case closed. (If you want to see the transcript yourself, go to www.senate.gov/reference/resources/pdf/ollie.pdf.)

Incidentally, North himself has tried to set the record straight a number of times. On his own website (www.olivernorth.com), he writes that he has received “several thousand e-mails from every state in the U.S. and 13 foreign countries” asking about the bin Laden hoax message, which he called “simply inaccurate.”

Finding the Good Stuff

We could cite countless examples here of false information floating around the Internet; you probably have seen plenty as well. The Internet is pure anarchy: more information is available more readily than ever before, but there are no regulations, no standards, and no penalties for making careless mistakes or even for telling the most outrageous conceivable whoppers. Fortunately, finding the good stuff can be fairly easy, and even fun. We've already demonstrated how quickly the Oliver North hoax could be shot down. The key is finding the right websites and knowing how to evaluate their reliability. In the remainder of this chapter, we'll share with you a few of the things we've learned at FactCheck.org about finding trustworthy information on the Web.

First and most important, consider the source. Who stands behind the information? The Ollie North hoax was anonymous, impossible to trace back to the person who originated it. The author claimed to have seen a videotape of North “at a lecture the other day,” which of course is also impossible to verify. Claims from such sources deserve no credence whatever because you have no idea who is making the claim, or why. Assume that anonymous or untraceable claims are false until proven otherwise.

The Hoax

This version was forwarded to FactCheck.org in 2006, but it's been around since 2001 and is only one of many we've been asked about.

Â

Anyone remember this?

Â

It was 1987! At a lecture the other day they were playing an old news video of Lt. Col. Oliver North testifying at the Iran-Contra hearings during the Reagan Administration.

There was Ollie in front of God and country getting the third degree, but what he said was stunning!

He was being drilled by a senator; “Did you not recently spend close to $60,000 for a home security system?”

Ollie replied, “Yes, I did, Sir.”

The senator continued, trying to get a laugh out of the audience, “Isn't that just a little excessive?”

“No, sir,” continued Ollie.

“No? And why not?” the senator asked.

“Because the lives of my family and I were threatened, sir.”

“Threatened? By whom?” the senator questioned.

“By a terrorist, sir” Ollie answered.

“Terrorist? What terrorist could possibly scare you that much?”

“His name is Osama bin Laden, sir” Ollie replied.

At this point the senator tried to repeat the name, but couldn't pronounce it, which most people back then probably couldn't. A couple of people laughed at the attempt. Then the senator continued. Why are you so afraid of this man?” the senator asked.

“Because, sir, he is the most evil person alive that I know of”, Ollie answered.

“And what do you recommend we do about him?” asked the senator.

“Well, sir, if it was up to me, I would recommend that an assassin team be formed to eliminate him and his men from the face of the earth.”

The senator disagreed with this approach, and that was all that was shown of the clip.

Â

By the way, that senator was Al Gore!

The Disproof

These are images of the transcript of North's actual testimony, taken from the official website of the U.S. Senate, at www.senate.gov/reference/resources/pdf/ollie.pdf:

Look instead for sources with authority. The U.S. Senate's historian is, obviously, an excellent source with respect to the Ollie North affair. When the Senate website posts pages from the official transcript of those hearings, you can be close to 100 percent certain that what you're reading is what North really said. North's own website is another good source, because the information is coming from North himself, and also because he is about the last person we'd expect to lie to protect a Democrat.

Government websites have as much authority and credibility as the agencies that stand behind them. To get the latest official estimate of the U.S. population, you can now go directly to the website of the Census Bureau, where you will also find official measures of poverty, income, the number of persons with and without health insurance, and much more. The figures we cited for causes of death among women came directly from the website of the National Center for Health Statistics, where the federal government posts its official tally of death records from all fifty states. And our figures showing the tiny percentage of affluent Americans who actually pay estate tax came from the website of the Internal Revenue Service, which publishes data taken directly from the tens of millions of tax forms it processes each year. At the National Aeronautics and Space Administration's website, you can find authoritative information on what scientists know about the solar system and the universe, including the latest on the expected recovery of the earth's protective ozone layer.

Look for a “dot-gov” extension on the website's address. For example, www.socialsecurity.gov is the home page of the U.S. Social Security Administration, where you can find the latest statistics on the system's financial troubles, provided by its board of trustees. There you will see that, unless Washington acts, benefits will have to be cut, or taxes increased, in 2040. You can also run down the most popular names for babies. In applications for Social Security cards, parents in 2005 chose Emily for girls and Jacob for boys more often than any other names. The dot-gov extension also can be used by state governments. For example, at www.ohio.gov you can see who's governor or read the state constitution or laws, and at the Ohio State Highway Patrol's site you can even get a satellite map of all the fatal car, truck, and motorcycle crashes in the state in 2005. That last may or may not be particularly useful, but since it comes from the Ohio State Highway Patrol, you can be reasonably sure it's correct.

We would never suggest that everything you find on a dot-gov website should be believed, of course. Apply thought and common sense, as you would anywhere else.

At www.whitehouse.gov, for example, you will find the words that President Bush has spoken at his public appearances, officially transcribed and in full context. You can be reasonably confident that those are Bush's exact words; the incidents where reporters' tapes differ from the official transcript are rare. But it's still up to you to decide whether you believe what Bush said. And also be careful when using House and Senate websites. For example, www.dems.gov takes you to the website of the House Democratic Caucus, made up of all the Democrats in the House, just as www.gop.gov takes you to the House Republican Conference. These partisan websites will tell you much about the current party line, but can't be expected to give a balanced account of the facts.

Most official House and Senate committee websites have been even worse, seeming to speak for the full committee but in fact posting only talking points for the party in the majority and omitting mention of the minority party's views. In 2006, www.waysandmeans.gov was run by Republicans, who controlled the House and the tax-writing Ways and Means Committee along with it. So it should be no surprise that the committee website contained a misleading press release praising a Republican bill that “would permanently eliminate the estate tax for 99.7 percent of all Americans.” That's misleading because you can't really “eliminate” a tax for the 99 percent who weren't liable for it in the first place.

*3

That release was typical of the slanted information on taxes and Republican-sponsored tax cuts that appeared on the committee's website.

With Republicans in control, reaching the site run by the Democrats on the Ways and Means Committee required a visitor to find the link labeled “Minority Website,” which appeared in tiny 8-point type hidden away near the bottom of the page. And the same went for nearly all other House and Senate committee websites: they spoke only for the majority party. When Democrats are in control these official sites may or may not become less partisan, so visitors should continue to be wary of them.

Not all committee sites were so one-sided. Two laudable exceptions were the Joint Committee on Taxation, which maintained a bipartisan staff of experts to estimate the effects of proposed tax bills on the federal budget, and the Congressional Budget Office, which did the same for a wide array of bills and government programs. That's something we hope will continue, but visitors should be alert for any changes as partisan control of Congress shifts.

Websites sponsored by academic institutions can contain a wealth of solid information. Here look for the “dot-edu” extension on the domain name, as in nahic.ucsf.edu. This is the website of the National Adolescent Health Information Center (NAHIC), which is associated with the department of pediatrics at the University of CaliforniaâSan Francisco. The “edu” in the domain name is short for “education,” and only universities, colleges, and other accredited institutions of higher learning are allowed to use it. Research librarians searching the Internet for information on a new topic will often limit their searches to dot-edu and dot-gov websites, knowing they are much more likely to find authoritative information there than on a dot-com or dot-org website, which anybody can own.

However, the dot-edu extension is no guarantee of accuracy. Consider the example of Michael Bellesiles's book on guns, discussed previously. Professors often post their current research papers on their own pages within the website of the college or university where they teach; while such papers can be excellent resources, they are also the work of only that one professor, and don't carry the weight of the institution. Some colleges even give students personal web pages along with their dorm rooms and gym cards, and those pages all have dot-edu extensions too. If you find something on a university website that seems to contain the information you need, dig a little until you are satisfied that it was put there by experts you can trust, not by a freshman who's about to flunk out.

News organizations also run websitesâfor example, www.cnn.com and www.nytimes.com. In general, you can trust these sites to the same degree you would trust the news organizations that stand behind them. The BBC News website is superb for international news often ignored by U.S. news organizations. There's no need to dismiss a news story just because it appears on the website of a local or regional newspaper: the website of the New Orleans

Times-Picayune

was among the very best sources of information for what was actually happening during the Hurricane Katrina disaster in 2005, for example. For three days, the newspaper published only on the Web, because its printing plant was underwater, and eventually the quality of its reporting earned its staff two Pulitzer Prizes, including a gold medal for meritorious public service and the prize for reporting of breaking news. In this case, the information on a local newspaper's website was far superior to that found on the government websites of, for example, FEMA and the Army Corps of Engineers.

Local newspapers also carry dispatches from The Associated Press, which still sets the standard for balanced, just-the-facts reporting of current events, at least in our view. (We may be a bit biased about The AP, because Brooks Jackson worked there until 1980.) A story with an AP byline carries The AP's authority, in addition to that of the newspaper that published it. For recent events, try using Google, Yahoo, or any other good Internet search engine that can limit the search to “news.” This should bring up any recent stories that contain the key words you have entered; frequently, the results will include several copies of the same AP story as reprinted in different places. However, these searches will also dredge up posts on all sorts of strongly partisan or ideological websites and blogs that can't necessarily be trusted to give a full or even an accurate account.