unSpun (16 page)

FINAL RULE:

Be Skeptical, but Not Cynical

T

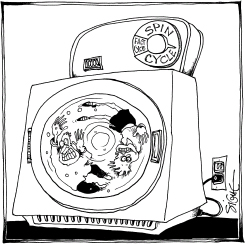

HE SKEPTIC DEMANDS EVIDENCE, AND RIGHTLY SO. THE CYNIC ASSUMES

that what he or she is being told is false. Throughout this book we've been urging you to be skeptical of factual claims, to demand and weigh the evidence and to keep your mind open. But too many people mistake cynicism for skepticism. Cynicism is a form of gullibilityâthe cynic rejects facts without evidence, just as the naïve person accepts facts without evidence. And deception born of cynicism can be just as costly or potentially as dangerous to health and well-being as any other form of deception.

To understand this notion, consider Kevin Trudeau, the author of a book that topped the

New York Times

best-seller list for a time in the summer of 2005:

Natural Cures “They” Don't Want You to Know About.

Trudeau pumped up sales with a massive campaign of late-night infomercials in which he claimed that “there are in fact natural, non-drug, and non-surgical cures for virtually every disease.” His basic claimâan appeal to cynicism that he repeated over and overâwas that “they” were conspiring to suppress information about known cures: “The drug companies don't want you to know the truth, the Food and Drug Administration, the U.S. government does not want you to know the truth. Why? Because it would cost them too much money in profits if you knew the inexpensive, natural remedies.”

Trudeau's pitch is that “they” are lying but

he

will tell you the truth. Just buy his $14.95 book ($39.95 on audio CDs,) or subscribe to his $71.40-a-year newsletter, or become a $999 “lifetime member.” And, oh, yes, buy his $19.95 weight-loss CD, whose title is, he claims, “censored by the Federal Trade Commission.” Did you know the FTC is in on the conspiracy, too? As is the food industry, which, Trudeau claims, is putting unspecified ingredients in “diet” products that actually make people fat. No wonder we can't lose weight! The “censored” title:

How to Lose 30 Pounds in 30 Days,

just the sort of extravagant and unsupported claim the FTC often cites as misleading advertising.

We call Trudeau's pitch an appeal to cynicism because he is trading on the public's belief the federal government can't be trusted, and that big corporationsâespecially pharmaceutical companiesâpursue profit so blindly that they are capable of almost any villainy. We might agree that some of the practices of drug companies justify criticism, but Trudeau is hoping you will automaticallyâcynicallyâaccept his claim that big companies and the government are secretly conspiring to make you fat. This tactic has made untold millions of dollars for him, unless he's conning the public about that, too. His company once claimed to have sold 4 million copies of his book alone. His marketing plan must still be working, because in May 2006 he came out with a sequel:

More Natural Cures Revealed: Previously Censored Brand Name Products That Cure Disease.

But here's why you should be skepticalâof Trudeau. Just do a little research using any Internet search engine and you will quickly discover a few facts about this master salesman:

⢠Trudeau has a criminal past. He served nearly two years in federal prison after a 1991 guilty plea to credit card fraud in which he bilked American Express of $122,735.68. In 1990, he served twenty-one days in jail and got a three-year suspended sentence on a Massachusetts state conviction for larceny after depositing $80,000 of worthless checks. At the time, he was posing as a doctor.

⢠Trudeau has been repeatedly cited for false advertising. In 1998, he agreed to pay $500,000 to settle FTC charges that he appeared in a string of infomercials that claimed, among other things, that his “Mega Memory System” could enable anyone to achieve a photographic memory. In 2003, the FTC and FDA charged him with falsely claiming in infomercials that a dietary supplement called Coral Calcium Supreme could cure cancer. He agreed to stop making such claims but then continued to do so anyway, leading a federal judge in Chicago to find him in contempt of court. Later in 2004, Trudeau agreed to pay $2 million to the FTC and to cease making infomercials selling any product at all, except for “informational” material, which is protected by the First Amendment. That was when he switched from selling pills to selling books, CDs, and newsletters.

The $2.5 million that Trudeau has paid to settle earlier false-advertising cases is probably chump change compared to what he's taking in from a public made gullible by its own cynicism. It is easy to see why Trudeau's appeal works so well. Politicians love to blame “corporate greed” whenever prices go up, and Hollywood loves to cast corporate executives as villains in movies and TV crime shows. Since the Watergate scandals and the Vietnam War, a large majority of Americans who once trusted government to do the right thing now say they believe it is controlled by special interests and not run for the common benefit. Public trust of drug companies is particularly low. But that shouldn't be a reason to fall for the unsupported claims of a convicted felon and incorrigible huckster who's making millions selling books about bogus “natural cures.” And anyone who tries using those “cures” instead of seeking competent medical advice is putting his or her health and even life at risk.

So we say cynicism can kill you. But you can save money, and maybe your life, if you are skeptical about claims like those made by Trudeau and the many others like him. Always look for real evidence.

Conclusion

Staying unSpun

S

TAYING UN

S

PUN REALLY BOILS DOWN TO FOLLOWING A FEW PRINCIPLES

that we've been talking about throughout this book. When confronted with a claim, keep an open mind, ask questions, cross-check, look for the best information, and then weigh the evidence.

CASE STUDY:

Hoodia Hoodoo

T

O SHOW HOW TO PUT THESE SIMPLE BUT POWERFUL MENTAL HABITS

into practice, let's walk through a quick fact-checking of a real-life claim you may already have encountered. Let's say you have seen on the CBS News website a snippet of a

60 Minutes

program in which correspondent Lesley Stahl is telling you about the next big thing in dieting: a rare South African cactus called Gordon's Hoodia (or

Hoodia gordonii

). Stahl is in the Kalahari Desert, where she says the native San tribes-people eat Hoodia to suppress their appetite on hunting trips. “Scientists say it fools the brain by making you think you're full, even if you've just eaten a morsel.” A weight-loss pill may soon be on the market. The Web version of the story carries the headline “African Plant May Help Fight Fat: Lesley Stahl Reports on Newest Weapon in War on Obesity.”

Hoodia gordonii, the rare South African cactus purported to

suppress appetite naturally

This is no late-night infomercial huckster talking; this is a tough reporter who once covered President Richard Nixon's Watergate scandal. Stahl reports that after eating a piece of the plant she went all day without feeling hungry, and that she experienced no aftereffects either. “I'd have to say it did work,” she reports.

Wow! Where can I get this stuff? You quickly search the Internet for “hoodia,” and find a cyber-bazaar of merchants hawking “Pure Hoodia,” “Pure Hoodia Plus,” “Hoodia Supreme,” “Desert Burn” Hoodia, and any number of other brands. You also see websites offering advice on finding the “best” Hoodia products among all the clamoring competitors. Several provide a link to a video clip from the

60 Minutes

program on the CBS News website. They feature testimonialsâfor example, one from “Sarah” of Los Angeles, who says, “I used to always have cravings at night, but those cravings went away.” This is sounding better and better.

But before you send off $149.95 for a five-month supply of this magical substance, take a few minutes to ask questions. How do I know this works, and is it safe? Just because Lesley Stahl swears by the freshly cut cactus she nibbled in the Kalahari Desert doesn't mean the capsules you buy from an Internet merchant will have the same effect, or even came from the same plant. And we had better dismiss those Internet testimonials: they're anecdotes at best, and they could be fabricated for all we know. Where are the scientific test results?

A bit of cross-checking turns up more information. Our Internet search has also brought up a 2003 story from a BBC reporter, Tom Mangold, who sampled the “Kalahari diet” even before Stahl. After eating a piece of cactus about half the size of a banana, Mangold reported that he and his cameraman “did not even think about food” for the four-hour drive back to Cape Town. “Dinnertime came and went. We reached our hotel at about midnight and went to bed without food. And the next day, neither of us wanted nor ate breakfast.” But read on.

The BBC story also warns us that the stuff we've been seeing advertised may be just another weight-loss scam. The rights to develop a diet drug from Hoodia are owned by a British company named Phytopharm, and clinical trials still have several years to run. The reporter adds: “And beware Internet sites offering Hoodia âpills' from the U.S., as we tested the leading brand and discovered it has no discernible Hoodia in it.” Oddly, several Hoodia hucksters actually post a link to this BBC story on their websites, probably figuring that few will actually read it and most will just assume it's an endorsement.

To be fair to CBS, Stahl's full report also warned against the claims of Internet marketers of Hoodia products. It mentioned that the wild cactus is so rare that Phytopharm has established a plantation in an attempt to grow it in the huge quantities that would be required to meet demand should tests prove that the product is safe and effective. But the Internet Hoodia merchants who link to the CBS report probably figure you won't notice that part. They just post a link to the story, with introductions such as “Leslie [

sic

] Stahlâ¦Hoodia works!!”

The BBC and CBS news storiesâread in fullâprovide pretty strong warnings about the stuff being sold on the Web, but they are still secondhand sources. We can do better. On the Phytopharm website, we read, “The necessary clinical trials and other studies to ensure the safety of the [Hoodia] extract will take a few years before a product will be available.” The site says that the company is just starting those trials, in collaboration with its partner Unilever. That tells us that this diet drug is far from ready for market.

At Phytopharm's site we also look for the “clinical study” conducted by the company in 2001 and mentioned in news reports and on many of the Hoodia websites. There is no report published in a medical journalâjust a news release. It says the company ran a test of nineteen overweight men, giving half of them their patented “P57” Hoodia extract for fifteen days, while the other half got a placebo. The group getting P57 were said to have “a statistically significant decrease in daily calorie intake,” a reduction of as much as 1,000 calories per day. We also learn from reading the company's press releases that before it hooked up with Unilever it had a deal with Pfizer to develop a commercial product from P57, but Pfizer backed out of the deal in 2003. Why would a major company drop a miracle weight-loss drug if it really had promise?

We've scouted up all this information for free, in a few minutes. For a small fee, you could have read on the

Consumer Reports

website an article briefly summarizing some of what we've said here, stating that there's “very scanty” evidence that Hoodia works, and concluding that “we do not recommend taking these supplements.” (For $26 a year, we consider a subscription to

Consumer Reports

magazine and the website to be a bargain.)

When we weigh this evidence, we find that there's good reason to ignore the Hoodia hype, at least for now. Our TV correspondents, Stahl and Mangold, both gave us impressive anecdotal accounts of eating fresh cactus, but we won't find any of that at the supermarket. A British company, reputable enough to have partnered first with Pfizer and currently with Unilever, says we won't be able to buy their product for years. What's being offered for sale in the United States is claimed to be the cactus in powdered form, but we have no reliable way of knowing whether it's really Hoodia or just sawdust, orâmore importantâwhether Hoodia powder works like fresh Hoodia. The testimonials we see on sellers' websites should be disregarded: we don't know who these people are, whether they really lost weight, or whether, if they did lose weight, the loss resulted from the pills. Furthermore, we have little idea of what harm these products might cause. Phytopharm's test group included only nineteen males. What if women took it? What if one person in every thousand experiences a life-threatening reaction? What happens if people take it for six months instead of just two weeks? Does it cause liver damage? What if Phytopharm sponsored other studies that produced less impressive results, and hasn't released them? We don't know.

Respect for Facts

We're not surprised that advertisers and politicians try to deceive us. Who can blame them for fabricating, twisting, exaggerating, or distorting the facts when we customers and citizens reward them so regularly with our money and votes? We should know that products like “Exercise in a Bottle” or Internet-advertised Hoodia won't make fat melt away without effort on our part. We even joke about how untrustworthy politicians are when they seek our votes. And yet enough people buy the products and the candidates to make all the spinning pay off.

These hucksters and partisans may not even realize how badly they are misleading us. Quite often, they seem to believe their own spin, even when a bit of rudimentary fact-checking shows it to be distorted or false. Remember the “your brain on politics” scans? In true believers, the portions of the brain used in rational thought just didn't light up. But from the consumer's standpointâor the voter'sâit doesn't matter whether the deception and spinning are deliberate. Either way, getting the facts wrong can cause us to waste six bucks on a cold remedy that may not work, or cause us to cheer for a war that doesn't look like such a good idea once we find out our leaders got the basic facts wrong.

So what can we do? Certainly an ordinary citizen can't be expected to outguess the CIA about the secret military capabilities of foreign nations. And maybe it's no big tragedy if we overpay for beauty products that don't really make wrinkles disappear. Indeed, maybe just thinking that wrinkles are gone is worth the money to some, and they might not mind being deceived. But generally, we're better off getting facts right, and we should try to get them right as consistently as we can.

Our advice boils down to two words: respect facts.

You'll be money ahead, for one thing. A little fact-checking is often all it takes to expose the advertising hype of an emu-oil saleswoman, a “clinically proven” cold remedy that isn't really proven, or an ex-con selling a book about cancer cures on late-night infomercials.

You'll save yourself time and annoyance if you develop the habits of mind we have recommended here. Respect for facts means keeping your mind engaged, so you won't fall for the next psychology student who cuts in line at the copy machine with a nonreason like “I have to make some copies,” or for the many other nonreasons and the bogus logic that we're confronted with every day. Respect for facts also means checking your own assumptions. You could live years longer if you are a woman who respects the facts about what most women really die of, and then follows the medical advice that reduces those risks. You could avoid dying young if you are a teenager who respects the fact that teen drivers are four times more likely than older drivers to crash. Most teens don't; they tend to rate their own skills higher than those of their peers.

When it comes to politics, you can have the satisfaction of knowing you chose your candidate on the basis of facts, not just TV-spot fantasies. It might not change the way you vote, but then again, it might. Either way, you can be more confident you've made the right choice.

A greater respect for facts among our leaders could well have avoided a protracted and bloody war in Iraq. CIA officials failed to practice active open-mindedness, while the president and his top advisers pushed for evidence that would confirm their assumptions, not for evidence that might disprove them and show war to be unnecessary. The opposition showed little respect for facts as well: only half a dozen senators and a handful of House members even bothered to read the full National Intelligence Estimate prior to voting to authorize force.

The New York Times

apologized in 2004 for failing to report more skeptically in the months before the war.

We don't expect that one voter will change the way presidents or CIA directors or news organizations do their jobs. We don't expect that a single customer can bring about an end to bogus sales pitches. However, we do think that a movement of citizens can change these things. Start with the little things, such as what cold remedy to buy. Practice the habits of mind and the fact-checking skills we've suggested here. Apply those methods to more important matters. Then demand better. Don't reward those who disrespect facts, by buying their products or by voting for them. Do insist that they respect facts, respect you, and respect your intelligence and good sense. If enough of us do that, we believe that eventually our leaders will follow. When a group you support gets something wrong, speak up and ask them to correct it, as many NARAL supporters did when their group ran that ad we mentioned falsely accusing John Roberts of endorsing violence. If all sides in the political debate did that, the quality of discussion would rise.

You think our theory is goofy? It's up to you to show us the evidence. Try what we're suggesting. Prove us wrong.