The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order (13 page)

Read The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order Online

Authors: Samuel P. Huntington

Tags: #Current Affairs, #History, #Modern Civilization, #Non-fiction, #Political Science, #Scholarly/Educational, #World Politics

Islamic societies have had difficulty with modernization, and Pipes supports

p. 78

his claim that Westernization is a prerequisite by pointing to the conflicts between Islam and modernity in economic matters such as interest, fasting, inheritance laws, and female participation in the work force. Yet even he approvingly quotes Maxine Rodinson to the effect that “there is nothing to indicate in a compelling way that the Muslim religion prevented the Muslim world from developing along the road to modern capitalism” and argues that in most matters other than economic

Islam and modernization do not clash. Pious Muslims can cultivate the sciences, work efficiently in factories, or utilize advanced weapons. Modernization requires no one political ideology or set of institutions: elections, national boundaries, civic associations, and the other hallmarks of Western life are not necessary to economic growth. As a creed, Islam satisfies management consultants as well as peasants. The Shari’a has nothing to say about the changes that accompany modernization, such as the shift from agriculture to industry, from countryside to city, or from social stability to social flux; nor does it impinge on such matters as mass education, rapid communications, new forms of transportation, or health care.

[47]

Similiarly, even extreme proponents of anti-Westernism and the revitalization of indigenous cultures do not hesitate to use modern techniques of e-mail, cassettes, and television to promote their cause.

Modernization, in short, does not necessarily mean Westernization. Non-Western societies can modernize and have modernized without abandoning their own cultures and adopting wholesale Western values, institutions, and practices. The latter, indeed, may be almost impossible: whatever obstacles non-Western cultures pose to modernization pale before those they pose to Westernization. It would, as Braudel observes, almost “be childish” to think that modernization or the “triumph of

civilization

in the singular” would lead to the end of the plurality of historic cultures embodied for centuries in the world’s great civilizations.

[48]

Modernization, instead, strengthens those cultures and reduces the relative power of the West. In fundamental ways, the world is becoming more modern and less Western.

Chapter 4 – The Fading of the West: Power, Culture, and Indigenization

Western Power: Dominance And Decline

p. 81

T

wo pictures exist of the power of the West in relation to other civilizations. The first is of overwhelming, triumphant, almost total Western dominance. The disintegration of the Soviet Union removed the only serious challenger to the West and as a result the world is and will be shaped by the goals, priorities, and interests of the principal Western nations, with perhaps an occasional assist from Japan. As the one remaining superpower, the United States together with Britain and France make the crucial decisions on political and security issues; the United States together with Germany and Japan make the crucial decisions on economic issues. The West is the only civilization which has substantial interests in every other civilization or region and has the ability to affect the politics, economics, and security of every other civilization or region. Societies from other civilizations usually need Western help to achieve their goals and protect their interests. Western nations, as one author summarized it:

•

Own and operate the international banking system

•

Control all hard currencies

•

Are the world’s principal customer

•

Provide the majority of the world’s finished goods

•

Dominate international capital markets

•

Exert considerable moral leadership within many societies

•

Are capable of massive military intervention

•

Control the sea lanes

•

p. 82

Conduct most advanced technical research and development

•

Control leading edge technical education

•

Dominate access to space

•

Dominate the aerospace industry

•

Dominate international communications

•

Dominate the high-tech weapons industry

[1]

The second picture of the West is very different. It is of a civilization in decline, its share of world political, economic, and military power going down relative to that of other civilizations. The West’s victory in the Cold War has produced not triumph but exhaustion. The West is increasingly concerned with its internal problems and needs, as it confronts slow economic growth, stagnating populations, unemployment, huge government deficits, a declining work ethic, low savings rates, and in many countries including the United States social disintegration, drugs, and crime. Economic power is rapidly shifting to East Asia, and military power and political influence are starting to follow. India is on the verge of economic takeoff and the Islamic world is increasingly hostile toward the West. The willingness of other societies to accept the West’s dictates or abide its sermons is rapidly evaporating, and so are the West’s self-confidence and will to dominate. The late 1980s witnessed much debate about the declinist thesis concerning the United States. In the mid-1990s, a balanced analysis came to a somewhat similar conclusion:

[I]n many important respects, its [the United States’] relative power will decline at an accelerating pace. In terms of its raw economic capabilities, the position of the United States in relation to Japan and eventually China is likely to erode still further. In the military realm, the balance of effective capabilities between the United States and a number of growing regional powers (including, perhaps, Iran, India, and China) will shift from the center toward the periphery. Some of America’s structural power will flow to other nations; some (and some of its soft power as well) will find its way into the hands of nonstate actors like multinational corporations.

[2]

Which of these two contrasting pictures of the place of the West in the world describes reality? The answer, of course, is: they both do. The West is overwhelmingly dominant now and will remain number one in terms of power and influence well into the twenty-first century. Gradual, inexorable, and fundamental changes, however, are also occurring in the balances of power among civilizations, and the power of the West relative to that of other civilizations will continue to decline. As the West’s primacy erodes, much of its power will simply evaporate and the rest will be diffused on a regional basis among the several major civilizations and their core states. The most significant increases in power are accruing and will accrue to Asian civilizations, with China gradu

p. 83

ally emerging as the society most likely to challenge the West for global influence. These shifts in power among civilizations are leading and will lead to the revival and increased cultural assertiveness of non-Western societies and to their increasing rejection of Western culture.

The decline of the West has three major characteristics.

First, it is a slow process. The rise of Western power took four hundred years. Its recession could take as long. In the 1980s the distinguished British scholar Hedley Bull argued that “European or Western dominance of the universal international society may be said to have reached its apogee about the year 1900.”

[3]

Spengler’s first volume appeared in 1918 and the “decline of the West” has been a central theme in twentieth-century history. The process itself has stretched out through most of the century. Conceivably, however, it could accelerate. Economic growth and other increases in a country’s capabilities often proceed along an

S

curve: a slow start then rapid acceleration followed by reduced rates of expansion and leveling off. The decline of countries may also occur along a reverse

S

curve, as it did with the Soviet Union: moderate at first then rapidly accelerating before bottoming out. The decline of the West is still in the slow first phase, but at some point it might speed up dramatically.

Second, decline does not proceed in a straight line. It is highly irregular with pauses, reversals, and reassertions of Western power following manifestations of Western weakness. The open democratic societies of the West have great capacities for renewal. In addition, unlike many civilizations, the West has had two major centers of power. The decline which Bull saw starting about 1900 was essentially the decline of the European component of Western civilization. From 1910 to 1945 Europe was divided against itself and preoccupied with its internal economic, social, and political problems. In the 1940s, however, the American phase of Western domination began, and in 1945 the United States briefly dominated the world to an extent almost comparable to the combined Allied Powers in 1918. Postwar decolonization further reduced European influence but not that of the United States, which substituted a new transnational imperialism for the traditional territorial empire. During the Cold War, however, American military power was matched by that of the Soviets and American economic power declined relative to that of Japan. Yet periodic efforts at military and economic renewal did occur. In 1991, indeed, another distinguished British scholar, Barry Buzan, argued that “The deeper reality is that the centre is now more dominant, and the periphery more subordinate, than at any time since decolonization began.”

[4]

The accuracy of that perception, however, fades as the military victory that gave rise to it also fades into history.

Third, power is the ability of one person or group to change the behavior of another person or group. Behavior may be changed through inducement, coercion, or exhortation, which require the power-wielder to have economic, military, institutional, demographic, political, technological, social, or other resources. The power of a state or group is hence normally estimated by

p. 84

measuring the resources it has at its disposal against those of the other states or groups it is trying to influence. The West’s share of most, but not all, of the important power resources peaked early in the twentieth century and then began to decline relative to those of other civilizations.

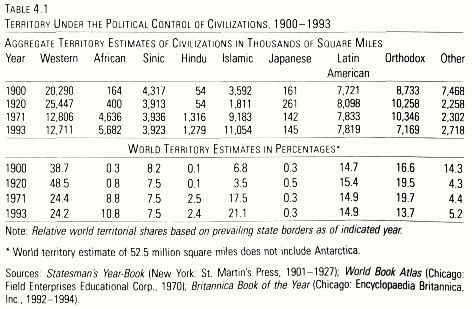

In 1490 Western societies controlled most of the European peninsula outside the Balkans or perhaps 1.5 million square miles out of a global land area (apart from Antarctica) of 52.5 million square miles. At the peak of its territorial expansion in 1920, the West directly ruled about 25.5 million square miles or close to half the earth’s earth. By 1993 this territorial control had been cut in half to about 12.7 million square miles. The West was back to its original European core plus its spacious settler-populated lands in North America, Australia, and New Zealand. The territory of independent Islamic societies, in contrast, rose from 1.8 million square miles in 1920 to over 11 million square miles in 1993. Similar changes occurred in the control of population. In 1900 Westerners composed roughly 30 percent of the world’s population and Western governments ruled almost 45 percent of that population then and 48 percent in 1920. In 1993, except for a few small imperial remnants like Hong Kong, Western governments ruled no one but Westerners. Westerners amounted to slightly over 13 percent of humanity and are due to drop to about 11 percent early in the next century and to 10 percent by 2025.

[5]

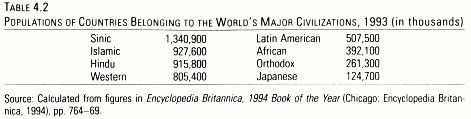

In terms of total population, in 1993 the West ranked fourth behind Sinic, Islamic, and Hindu civilizations.

Table 4.1 – Territory Under the Political Control of Civilizations, 1900-1993

Table 4.2 – Populations of Countries Belonging to the World’s Major Civilizations, 1993