The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order (17 page)

Read The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order Online

Authors: Samuel P. Huntington

Tags: #Current Affairs, #History, #Modern Civilization, #Non-fiction, #Political Science, #Scholarly/Educational, #World Politics

In addition to the psychological, emotional, and social traumas of modernization, other stimulants to religious revival included the retreat of the West and the end of the Cold War. Beginning in the nineteenth century, the responses of non-Western civilizations to the West generally moved through a progression of ideologies imported from the West. In the nineteenth century non-Western elites imbibed Western liberal values, and their first expressions of opposition to the West took the form of liberal nationalism. In the twentieth century Russian, Asian, Arab, African, and Latin American elites imported socialist and Marxist ideologies and combined them with nationalism in opposition to Western capitalism and Western imperialism. The collapse of communism in the Soviet Union, its severe modification in China, and the failure of socialist economies to achieve sustained development have now created an ideological vacuum. Western governments, groups, and international institutions, such as the IMF and World Bank, have attempted to fill this vacuum with the doctrines of neo-orthodox economics and democratic politics. The extent to which these doctrines will have a lasting impact in non-Western cultures is uncertain. Meanwhile, however, people see communism as only the latest secular god to have failed, and in the absence of compelling new secular deities they turn with relief and passion to the real thing. Religion takes over from ideology, and religious nationalism replaces secular nationalism.

[34]

The movements for religious revival are antisecular, antiuniversal, and, except in their Christian manifestations, anti-Western. They also are opposed to the relativism, egotism, and consumerism associated with what Bruce B. Lawrence has termed “modernism” as distinct from “modernity.” By and large they do not reject urbanization, industrialization, development, capitalism, science, and technology, and what these imply for the organization of society. In this sense, they are not antimodern. They accept modernization, as Lee Kuan Yew observes, and “the inevitability of science and technology and the change in the life-styles they bring,” but they are “unreceptive to the idea that they be Westernized.” Neither nationalism nor socialism, al-Turabi argues, produced development in the Islamic world. “Religion is the motor of development,” and a purified Islam will play a role in the contemporary era comparable to that of the Protestant ethic in the history of the West. Nor is religion incompatible with the develop

p. 101

ment of a modern state.

[35]

Islamic fundamentalist movements have been strong in the more advanced and seemingly more secular Muslim societies, such as Algeria, Iran, Egypt, Lebanon, and Tunisia.

[36]

Religious movements, including particularly fundamentalist ones, are highly adept at using modern communications and organizational techniques to spread their message, illustrated most dramatically by the success of Protestant televangelism in Central America.

Participants in the religious resurgence come from all walks of life but overwhelmingly from two constituencies, both urban and both mobile. Recent migrants to the cities generally need emotional, social, and material support and guidance, which religious groups provide more than any other source. Religion for them, as Régis Debray put it, is not “the opium of the people, but the vitamin of the weak.”

[37]

The other principal constituency is the new middle class embodying Dore’s “second-generation indigenization phenomenon.” The activists in Islamic fundamentalist groups are not, as Kepel points out, “aging conservatives or illiterate peasants.” With Muslims as with others, the religious revival is an urban phenomenon and appeals to people who are modern-oriented, well-educated, and pursue careers in the professions, government, and commerce.

[38]

Among Muslims, the young are religious, their parents secular. Much the same is the case with Hinduism, where the leaders of revivalist movements again come from the indigenized second generation and are often “successful businessmen and administrators” labeled in the Indian press “Scuppies”—saffron-clad yuppies. Their supporters in the early 1990s were increasingly from “India’s solid middle class Hindus—its merchants and accountants, its lawyers and engineers” and from its “senior civil servants, intellectuals, and journalists.”

[39]

In South Korea, the same types of people increasingly filled Catholic and Presbyterian churches during the 1960s and 1970s.

Religion, indigenous or imported, provides meaning and direction for the rising elites in modernizing societies. “The attribution of value to a traditional religion,” Ronald Dore noted, “is a claim to parity of respect asserted against ‘dominant other’ nations, and often, simultaneously and more proximately, against a local ruling class which has embraced the values and life-styles of those dominant other nations.” “More than anything else,” William McNeill observes, “reaffirmation of Islam, whatever its specific sectarian form, means the repudiation of European and American influence upon local society, politics, and morals.”

[40]

In this sense, the revival of non-Western religions is the most powerful manifestation of anti-Westernism in non-Western societies. That revival is not a rejection of modernity; it is a rejection of the West and of the secular, relativistic, degenerate culture associated with the West. It is a rejection of what has been termed the “Westoxification” of non-Western societies. It is a declaration of cultural independence from the West, a proud statement that: “We will be modern but we won’t be you.”

p. 102

I

ndigenization and the revival of religion are global phenomena. They have been most evident, however, in the cultural assertiveness and challenges to the West that have come from Asia and from Islam. These have been the dynamic civilizations of the last quarter of the twentieth century. The Islamic challenge is manifest in the pervasive cultural, social, and political resurgence of Islam in the Muslim world and the accompanying rejection of Western values and institutions. The Asian challenge is manifest in all the East Asian civilizations—Sinic, Japanese, Buddhist, and Muslim—and emphasizes their cultural differences from the West and, at times, the commonalities they share, often identified with Confucianism. Both Asians and Muslims stress the superiority of their cultures to Western culture. In contrast, people in other non-Western civilizations—Hindu, Orthodox, Latin American, African—may affirm the distinctive character of their cultures, but as of the mid-1990s had been hesitant about proclaiming their superiority to Western culture. Asia and Islam stand alone, and at times together, in their increasingly confident assertiveness with respect to the West.

Related but different causes lie behind these challenges. Asian assertiveness is rooted in economic growth; Muslim assertiveness stems in considerable measure from social mobilization and population growth. Each of these challenges is having and will continue to have into the twenty-first century a highly destabilizing impact on global politics. The nature of those impacts, however, differs significantly. The economic development of China and other Asian societies provides their governments with both the incentives and the resources

p. 103

to become more demanding in their dealing with other countries. Population growth in Muslim countries, and particularly the expansion of the fifteen- to twenty-four-year-old age cohort, provides recruits for fundamentalism, terrorism, insurgency, and migration. Economic growth strengthens Asian governments; demographic growth threatens Muslim governments and non-Muslim societies.

The economic development of East Asia has been one of the most significant developments in the world in the second half of the twentieth century. This process began in Japan in the 1950s, and for a while Japan was thought to be the great exception: a non-Western country that had successfully modernized and become economically developed. The process of economic development, however, spread to the Four Tigers (Hong Kong, Taiwan, South Korea, Singapore) and then to China, Malaysia, Thailand, and Indonesia, and is taking hold in the Philippines, India, and Vietnam. These countries have often sustained for a decade or more average annual growth rates of 8-10 percent or more. An equally dramatic expansion of trade has occurred first between Asia and the world and then within Asia. This Asian economic performance contrasts dramatically with the modest growth of the European and American economics and the stagnation that has pervaded much of the rest of the world.

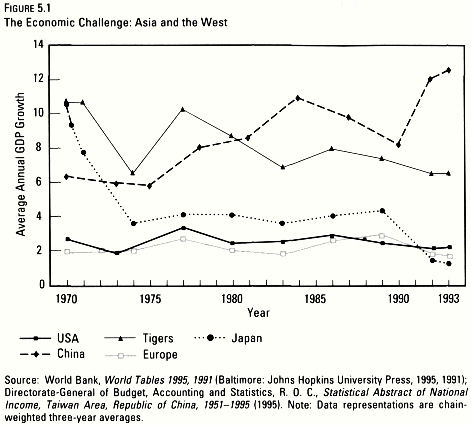

The exception is thus no longer just Japan, it is increasingly all of Asia. The identity of wealth with the West and underdeveloprnent with the non-West will not outlast the twentieth century. The speed of this transformation has been overwhelming. As Kishore Mahbubani has pointed out, it took Britain and the United States fifty-eight years and forty-seven years, respectively, to double their per capita output, but Japan did it in thirty-three years, Indonesia in seventeen, South Korea in eleven, and China in ten. The Chinese economy grew at annual rates averaging 8 percent during the 1980s and the first half of the 1990s, and the Tigers were close behind (see

Figure 5.1

). The “Chinese Economic Area,” the World Bank declared in 1993, had become the world’s “fourth growth pole,” along with the United States, Japan, and Germany. According to most estimates, the Chinese economy will become the world’s largest early in the twenty-first century. With the second and third largest economies in the world in the 1990s, Asia is likely to have four of the five largest and seven of the ten largest economies by 2020. By that date Asian societies are likely to account for over 40 percent of the global economic product. Most of the more competitive economies will also probably be Asian.

[1]

Even if Asian economic growth levels off sooner and more precipitously than expected, the consequences of the growth that has already occurred for Asia and the world are still enormous.

Figure 5.1 – The Economic Challenge: Asia and the West

East Asian economic development is altering the balance of power between

p. 104

Asia and the West, specifically the United States. Successful economic development generates self-confidence and assertiveness on the part of those who produce it and benefit from it. Wealth, like power, is assumed to be proof of virtue, a demonstration of moral and cultural superiority. As they have become more successful economically, East Asians have not hesitated to emphasize the distinctiveness of their culture and to trumpet the superiority of their values and way of life compared to those of the West and other societies. Asian societies are decreasingly responsive to U.S. demands and interests and increasingly able to resist pressure from the United States or other Western countries.

A “cultural renaissance,” Ambassador Tommy Koh noted in 1993, “is sweeping across” Asia. It involves a “growing self-confidence,” which means Asians “no longer regard everything Western or American as necessarily the best.”

[2]

This renaissance manifests itself in increasing emphasis on both the distinctive cultural identities of individual Asian countries and the commonalities of Asian cultures which distinguish them from Western culture. The significance of this cultural revival is written in the changing interaction of East Asia’s two major societies with Western culture.

When the West forced itself on China and Japan in the mid-nineteenth

p. 105

century, after a momentary infatuation with Kemalism, the prevailing elites opted for a reformist strategy. With the Meiji Restoration a dynamic group of reformers came to power in Japan, studied and borrowed Western techniques, practices, and institutions, and started the process of Japanese modernization. They did this in such a way, however, as to preserve the essentials of traditional Japanese culture, which in many respects contributed to modernization and which made it possible for Japan to invoke, reformulate, and build on the elements of that culture to arouse support for and justify its imperialism in the 1930s and 1940s. In China, on the other hand, the decaying Ch’ing dynasty was unable to adapt successfully to the impact of the West. China was defeated, exploited, and humiliated by Japan and the European powers. The collapse of the dynasty in 1910 was followed by division, civil war, and invocation of competing Western concepts by competing Chinese intellectual and political leaders: Sun Yat Sen’s three principles of “Nationalism, Democracy, and the People’s Livelihood”; Liang Ch’i-ch’ao’s liberalism; Mao Tse-tung’s Marxist-Leninism. At the end of the 1940s the import from the Soviet Union won out over those from the West—nationalism, liberalism, democracy, Christianity—and China was defined as a socialist society.

In Japan total defeat in World War II produced total cultural discombobulation. “It is very difficult now,” one Westerner deeply involved in Japan commented in 1994, “for us to appreciate the extent to which everything—religion, culture, every single aspect of this country’s mental existence—was drawn into the service of that war. The loss of the war was a complete shock to the system. In their minds the whole thing became worthless and was thrown out.”

[3]

In its place, everything connected with the West and particularly the victorious United States came to be seen as good and desirable. Japan thus attempted to emulate the United States even as China emulated the Soviet Union.