The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order (14 page)

Read The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order Online

Authors: Samuel P. Huntington

Tags: #Current Affairs, #History, #Modern Civilization, #Non-fiction, #Political Science, #Scholarly/Educational, #World Politics

Table 4.3 – Shares of World Population Under the Political Control of Civilizations, 1900-2025

Quantitatively Westerners thus constitute a steadily decreasing minority of

p. 85

the world’s population. Qualitatively the balance between the West and other populations is also changing. Non-Western peoples are becoming healthier, more urban, more literate, better educated. By the early 1990s infant mortality rates in Latin America, Africa, the Middle East, South Asia, East Asia, and Southeast Asia were one-third to one-half what they had been thirty years earlier. Life expectancy in these regions had increased significantly, with gains varying from eleven years in Africa to twenty-three years in East Asia. In the early 1960s in most of the Third World less than one-third of the adult population was literate. In the early 1990s, in very few countries apart from Africa was less than one-half the population literate. About fifty percent of Indians and 75 percent of Chinese could read and write. Literacy rates in developing countries in 1970 averaged 41 percent of those in developed countries; in 1992 they averaged 71 percent. By the early 1990s in every region except Africa virtually the entire age group was enrolled in primary education. Most significantly, in the early 1960s in Asia, Latin America, the Middle East, and Africa less than

p. 86

one-third of the appropriate age group was enrolled in secondary education; by the early 1990s one-half of the age group was enrolled except in Africa. In 1960 urban residents made up less than one-quarter of the population of the less developed world. Between 1960 and 1992, however, the urban percentage of the population rose from 49 percent to 73 percent in Latin America, 34 percent to 55 percent in Arab countries, 14 percent to 29 percent in Africa, 18 percent to 27 percent in China, and 19 percent to 26 percent in India.

[6]

These shifts in literacy, education, and urbanization created socially mobilized populations with enhanced capabilities and higher expectations who could be activated for political purposes in ways in which illiterate peasants could not. Socially mobilized societies are more powerful societies. In 1953, when less than 15 percent of Iranians were literate and less than 17 percent urban, Kermit Roosevelt and a few CIA operatives rather easily suppressed an insurgency and restored the Shah to his throne. In 1979, when 50 percent of Iranians were literate and 47 percent lived in cities, no amount of U.S. military power could have kept the Shah on his throne. A significant gap still separates Chinese, Indians, Arabs, and Africans from Westerners, Japanese, and Russians. Yet the gap is narrowing rapidly. At the same time, a different gap is opening. The average ages of Westerners, Japanese, and Russians are increasingly steadily, and the larger proportion of the population that no longer works imposes a mounting burden on those still productively employed. Other civilizations are burdened by large numbers of children, but children are future workers and soldiers.

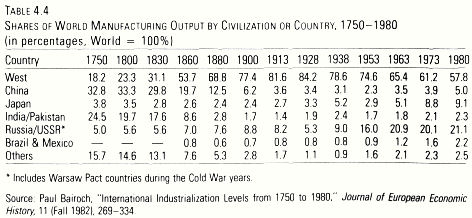

The Western share of the global economic product also may have peaked in the 1920s and has clearly been declining since World War II. In 1750 China accounted for almost one-third, India for almost one-quarter, and the West for less than a fifth of the world’s manufacturing output. By 1830 the West had pulled slightly ahead of China. In the following decades, as Paul

p. 87

Bairoch points out, the industrialization of the West led to the deindustrialization of the rest of the world. In 1913 the manufacturing output of non-Western countries was roughly two-thirds what it had been in 1800. Beginning in the mid-nineteenth century the Western share rose dramatically, peaking in 1928 at 84.2 percent of world manufacturing output. Thereafter the West’s share declined as its rate of growth remained modest and as less industrialized countries expanded their output rapidly after World War II. By 1980 the West accounted for 57.8 percent of global manufacturing output, roughly the share it had 120 years earlier in the 1860s.

[7]

Table 4.4 – Shares of World Manufacturing Output by Civilization or Country, 1750-1980

Table 4.5 – Civilization Shares of World Gross Economic Product, 1950-1992

Reliable data on gross economic product are not available for the pre-World War II period. In 1950, however, the West accounted for roughly 64 percent of the gross world product; by the 1980s this proportion had dropped to 49 percent. (See

Table 4.5

.) By 2013, according to one estimate, the West will account for only 30% of the world product. In 1991, according to another estimate, four of the world’s seven largest economies belonged to non-Western nations: Japan (in second place), China (third), Russia (sixth), and India (seventh). In 1992 the United States had the largest economy in the world, and the top ten economies included those of five Western countries plus the leading states of five other civilizations: China, Japan, India, Russia, and Brazil. In 2020 plausible projections indicate that the top five economies will be in five different civilizations, and the top ten economies will include only three Western countries. This relative decline of the West is, of course, in large part a function of the rapid rise of East Asia.

[8]

Gross figures on economic output partially obscure the West’s qualitative advantage. The West and Japan almost totally dominate advanced technology industries. Technologies are being disseminated, however, and if the West wishes to maintain its superiority it will do what it can to minimize that dissemination. Thanks to the interconnected world which the West has created,

p. 88

however, slowing the diffusion of technology to other civilizations is increasingly difficult. It is made all the more so in the absence of a single, overpowering, agreed-upon threat such as existed during the Cold War and gave measures of technology control some modest effectiveness.

It appears probable that for most of history China had the world’s largest economy. The diffusion of technology and the economic development of non-Western societies in the second half of the twentieth century are now producing a return to the historical pattern. This will be a slow process, but by the middle of the twenty-first century, if not before, the distribution of economic product and manufacturing output among the leading civilizations is likely to resemble that of 1800. The two-hundred-year Western “blip” on the world economy will be over.

Military power has four dimensions: quantitative—the numbers of men, weapons, equipment, and resources; technological—the effectiveness and sophistication of weapons and equipment; organizational—the coherence, discipline, training, and morale of the troops and the effectiveness of command and control relationships; and societal—the ability and willingness of the society to apply military force effectively. In the 1920s the West was far ahead of everyone else in all these dimensions. In the years since, the military power of the West has declined relative to that of other civilizations, a decline reflected in the shifting balance in military personnel, one measure, although clearly not the most important one, of military capability. Modernization and economic development generate the resources and desire for states to develop their military capabilities, and few states fail to do so. In the 1930s Japan and the Soviet Union created very powerful military forces, as they demonstrated in World War II. During the Cold War the Soviet Union had one of the world’s two most powerful military forces. Currently the West mo

p. 89

nopolizes the ability to deploy substantial conventional military forces anywhere in the world. Whether it will continue to maintain that capability is uncertain. It seems reasonably certain, however, that no non-Western state or group of states will create a comparable capability during the coming decades.

Overall, the years after the Cold War have been dominated by five major trends in the evolution of global military capabilities.

Table 4.6 – Civilization Shares of Total World Military Manpower

First, the armed forces of the Soviet Union ceased to exist shortly after the Soviet Union ceased to exist. Apart from Russia, only Ukraine inherited significant military capabilities. Russian forces were greatly reduced in size and were withdrawn from Central Europe and the Baltic states. The Warsaw Pact ended. The goal of challenging the U.S. Navy was abandoned. Military equipment was either disposed of or allowed to deteriorate and become nonoperational. Budget allocations for defense were drastically reduced. Demoralization pervaded the ranks of both officers and men. At the same time the Russian military were redefining their missions and doctrine and restructuring themselves for their new roles in protecting Russians and dealing with regional conflicts in the near abroad.

Second, the precipitous reduction in Russian military capabilities stimulated a slower but significant decline in Western military spending, forces, and capabilities. Under the plans of the Bush and Clinton administrations, U.S. military spending was due to drop by 35 percent from $342.3 billion (1994 dollars) in 1990 to $222.3 in 1998. The force structure that year would be half to two-thirds what it was at the end of the Cold War. Total military personnel would go down from 2.1 million to 1.4 million. Many major weapons programs have been and are being canceled. Between 1985 and 1995 annual purchases of major weapons went down from 29 to 6 ships, 943 to 127 aircraft, 720 to 0 tanks, and 48 to 18 strategic missiles. Beginning in the late 1980s, Britain, Germany, and, to a lesser degree, France went through similar reductions in defense spending and military capabilities. In the mid-1990s, the German armed forces were scheduled to decline from 370,000 to 340,000 and probably to 320,000; the French army was to drop from its strength of 290,000 in 1990 to 225,000 in 1997. British military personnel went down from 377,100 in 1985 to 274,800 in 1993. Continental members of NATO also shortened terms of conscripted service and debated the possible abandonment of conscription.

Third, the trends in East Asia differed significantly from those in Russia and the West. Increased military spending and force improvements were the order of the day; China was the pacesetter. Stimulated by both their increasing economic wealth and the Chinese buildup, other East Asian nations are modernizing and expanding their military forces. Japan has continued to improve its highly sophisticated military capability. Taiwan, South Korea, Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore, and Indonesia all are spending more on their military and purchasing planes, tanks, and ships from Russia, the United States, Britain,

p. 90

France, Germany, and other countries. While NATO defense expenditures declined by roughly 10 percent between 1985 and 1993 (from $539.6 billion to $485.0 billion) (constant 1993 dollars), expenditures in East Asia rose by 50 percent from $89.8 billion to $134.8 billion during the same period.

[9]

Fourth, military capabilities including weapons of mass destruction are diffusing broadly across the world. As countries develop economically, they generate the capacity to produce weapons. Between the 1960s and 1980s, for instance, the number of Third World countries producing fighter aircraft increased from one to eight, tanks from one to six, helicopters from one to six, and tactical missiles from none to seven. The 1990s have seen a major trend toward the globalization of the defense industry, which is likely further to erode Western mihtary advantages.

[10]

Many non-Western societies either have nuclear weapons (Russia, China, Israel, India, Pakistan, and possibly North Korea) or have been making strenuous efforts to acquire them (Iran, Iraq, Libya, and possibly Algeria) or are placing themselves in a position quickly to acquire them if they see the need to do so (Japan).