The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order (9 page)

Read The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order Online

Authors: Samuel P. Huntington

Tags: #Current Affairs, #History, #Modern Civilization, #Non-fiction, #Political Science, #Scholarly/Educational, #World Politics

It also has no implications for their attitudes toward the West. Somewhere in the Middle East a half-dozen young men could well be dressed in jeans, drinking Coke, listening to rap, and, between their bows to Mecca, putting together a bomb to blow up an American airliner. During the 1970s and 1980s Americans consumed millions of Japanese cars, TV sets, cameras, and electronic gadgets without being “Japanized” and indeed while becoming considerably more antagonistic toward Japan. Only naive arrogance can lead Westerners to assume that non-Westerners will become “Westernized” by acquiring Western goods. What, indeed, does it tell the world about the West when Westerners identify their civilization with fizzy liquids, faded pants, and fatty foods?

A slightly more sophisticated version of the universal popular culture argument focuses not on consumer goods generally but on the media, on Hollywood rather than Coca-Cola. American control of the global movie, television, and video industries even exceeds its dominance of the aircraft industry. Eighty-eight of the hundred films most attended throughout the world in 1993 were American, and two American and two European organizations dominate the collection and dissemination of news on a global basis.

[5]

This situation reflects two phenomena. The first is the universality of human interest in love, sex, violence, mystery, heroism, and wealth, and the ability of profit-motivated companies, primarily American, to exploit those interests to their own advan

p. 59

tage. Little or no evidence exists, however, to support the assumption that the emergence of pervasive global communications is producing significant convergence in attitudes and beliefs. “Entertainment,” as Michael Vlahos has said, “does not equate to cultural conversion.” Second, people interpret communications in terms of their own preexisting values and perspectives. “The same visual images transmitted simultaneously into living rooms across the globe,” Kishore Mahbubani observes, “trigger opposing perceptions. Western living rooms applaud when cruise missiles strike Baghdad. Most living outside see that the West will deliver swift retribution to non-white Iraqis or Somalis but not to white Serbians, a dangerous signal by any standard.”

[6]

Global communications are one of the most important contemporary manifestations of Western power. This Western hegemony, however, encourages populist politicians in non-Western societies to denounce Western cultural imperialism and to rally their publics to preserve the survival and integrity of their indigenous culture. The extent to which global communications are dominated by the West is, thus, a major source of the resentment and hostility of non-Western peoples against the West. In addition, by the early 1990s modernization and economic development in non-Western societies were leading to the emergence of local and regional media industries catering to the distinctive tastes of those societies.

[7]

In 1994, for instance, CNN International estimated that it had an audience of 55 million potential viewers, or about 1 percent of the world’s population (strikingly equivalent in number to and undoubtedly largely identical with the Davos Culture people), and its president predicated that its English broadcasts might eventually appeal to 2 to 4 percent of the market. Hence regional (i.e., civilizational) networks would emerge broadcasting in Spanish, Japanese, Arabic, French (for West Africa), and other languages. “The Global Newsroom,” three scholars concluded, “is still confronted with a Tower of Babel.”

[8]

Ronald Dore makes an impressive case for the emergence of a global intellectual culture among diplomats and public officials. Even he, however, comes to a highly qualified conclusion concerning the impact of intensified communications: “

other things being equal

[italics his], an increasing density of communication should ensure an increasing basis for fellow-feeling between the nations, or at least the middle classes, or at the very least the diplomats of the world,” but, he adds, “some of the things that may not be equal can be very important indeed.”

[9]

The central elements of any culture or civilization are language and religion. If a universal civilization is emerging, there should be tendencies toward the emergence of a universal language and a universal religion. This claim is often made with respect to language. “The world’s language is English,” as the editor of the

Wall Street journal

put it.

[10]

This can mean two things, only one of which would support the case for a universal civilization. It could mean that an increasing proportion of the world’s population speaks

p. 60

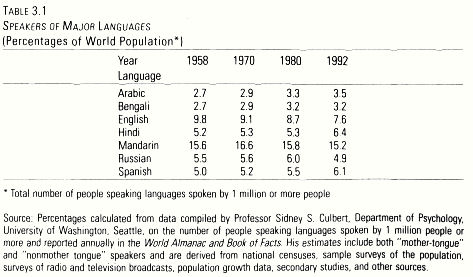

English. No evidence exists to support this proposition, and the most reliable evidence that does exist, which admittedly cannot be very precise, shows just the opposite. The available data covering more than three decades (1958-1992) suggest that the overall pattern of language use in the world did not change dramatically, that significant declines occurred in the proportion of people speaking English, French, German, Russian, and Japanese, that a smaller decline occurred in the proportion speaking Mandarin, and that increases occurred in the proportions of people speaking Hindi, Malay-Indonesian, Arabic, Bengali, Spanish, Portuguese, and other languages. English speakers in the world dropped from 9.8 percent of the people in 1958 speaking languages spoken by at least 1 million people to 7.6 percent in 1992 (see

Table 3.1

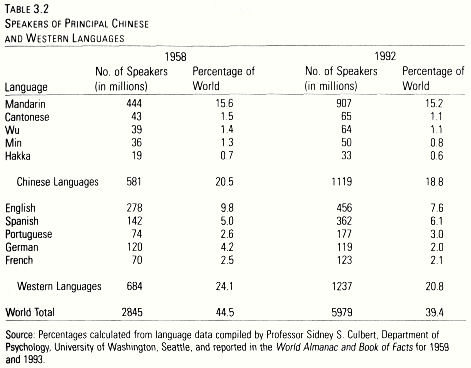

). The proportion of the world’s population speaking the five major Western languages (English, French, German, Portuguese, Spanish) declined from 24.1 percent in 1958 to 20.8 percent in 1992. In 1992 roughly twice as many people spoke Mandarin, 15.2 percent of the world’s population, as spoke English, and an additional 3.6 percent spoke other versions of Chinese (see

Table 3.2

).

Table 3.1 – Speakers of Major Languages

Table 3.2 – Speakers of Principal Chinese and Western Languages

In one sense, a language foreign to 92 percent of the people in the world cannot be the world’s language. In another sense, however, it could be so described, if it is the language which people from different language groups and cultures use to communicate with each other, if it is the world’s lingua franca, or in linguistic terms, the world’s principal Language of Wider Communication (LWC).

[11]

People who need to communicate with each other have to find means of doing so. At one level they can rely on specially trained professionals who have become fluent in two or more languages to serve as interpreters and translators. That, however, is awkward, time-consuming, and expensive. Hence throughout history lingua francas emerge, Latin in the Classical and

p. 61

medieval worlds, French for several centuries in the West, Swahili in many parts of Africa, and English throughout much of the world in the latter half of the twentieth century. Diplomats, businessmen, scientists, tourists and the services catering to them, airline pilots and air traffic controllers, need some means of efficient communication with each other, and now do it largely in English. In this sense, English is the world’s way of communicating interculturally just as the Christian calendar is the world’s way of tracking time, Arabic numbers are the world’s way of counting, and the metric system is, for the most part, the world’s way of measuring. The use of English in this way, however, is

intercultural

communication; it presupposes the existence of separate cultures. A lingua franca is a way of coping with linguistic and cultural differences, not a way of eliminating them. It is a tool for communication not a source of identity and community. Because a Japanese banker and an Indonesian businessman talk to each other in English does not mean that either one of them is being Anglofied or Westernized. The same can be said of German- and French-speaking Swiss who are as likely to communicate with each other in English as in either of their national languages. Similarly, the maintenance of English as an associate national language in India, despite Nehru’s plans to the contrary, testifies to the intense desires of the non-Hindi-speaking peoples of India to preserve their own languages and cultures and the necessity of India remaining a multilingual society.

p. 62

As the leading linguistic scholar Joshua Fishman has observed, a language is more likely to be accepted as a lingua franca or LWC if it is not identified with a particular ethnic group, religion, or ideology. In the past English had many of these identifications. More recently English has been “de-ethnicized (or minimally ethnicized)” as happened in the past with Akkadian, Aramaic, Greek, and Latin. “It is part of the relative good fortune of English as an additional language that neither its British nor its American fountainheads have been widely or deeply viewed in an ethnic or ideological context

for the past quarter century or so

” [Italics his].

[12]

The use of English for intercultural communication thus helps to maintain and, indeed, reinforces peoples’ separate cultural identities. Precisely because people want to preserve their own culture they use English to communicate with peoples of other cultures.

The people who speak English throughout the world also increasingly speak different Englishes. English is indigenized and takes on local colorations which distinguish it from British or American English and which, at the extreme, make these Englishes almost unintelligible one to the other, as is also the case with varieties of Chinese. Nigerian Pidgin English, Indian English, and other forms of English are being incorporated into their respective host cultures and presumably will continue to differentiate themselves so as to become related but distinct languages, even as Romance languages evolved out of Latin. Unlike Italian, French, and Spanish, however, these English-derived languages will either be spoken by only a small portion of people in the society or they will be used primarily for communication between particular linguistic groups.

All these processes can be seen at work in India. Purportedly, for instance, there were 18 million English speakers in 1983 out of a population of 733 million and 20 million in 1991 out of a population of 867 million. The proportion of English speakers in the Indian population has thus remained relatively stable at about 2 to 4 percent.

[13]

Outside of a relatively narrow elite, English does not even serve as a lingua franca. “The ground reality,” two professors of English at New Delhi University allege, “is that when one travels from Kashmir down to the southern-most tip at Kanyakumari, the communication link is best maintained through a form of Hindi rather than through English.” In addition, Indian English is taking on many distinctive characteristics of its own: it is being Indianized, or rather it is being localized as differences develop among the various speakers of English with different local tongues.

[14]

English is being absorbed into Indian culture just as Sanskrit and Persian were earlier.

Throughout history the distribution of languages in the world has reflected the distribution of power in the world. The most widely spoken languages—English, Mandarin, Spanish, French, Arabic, Russian—are or were the languages of imperial states which actively promoted use of their languages by other peoples. Shifts in the distribution of power produce shifts in the use of languages. “[T]wo centuries of British and American colonial, commercial,

p. 63

industrial, scientific, and fiscal power have left a substantial legacy in higher education, government, trade, and technology” throughout the world.

[15]

Britain and France insisted on the use of their languages in their colonies. Following independence, however, most of the former colonies attempted in varying degrees and with varying success to replace the imperial language with indigenous ones. During the heyday of the Soviet Union, Russian was the lingua franca from Prague to Hanoi. The decline of Russian power is accompanied by a parallel decline in the use of Russian as a second language. As with other forms of culture, increasing power generates both linguistic assertiveness by native speakers and incentives to learn the language by others. In the heady days immediately after the Berlin Wall came down and it seemed as if the united Germany was the new behemoth, there was a noticeable tendency for Germans fluent in English to speak German at international meetings. Japanese economic power has stimulated the learning of Japanese by non-Japanese, and the economic development of China is producing a similar boom in Chinese. Chinese is rapidly displacing English as the predominant language in Hong Kong

[16]

and, given the role of the overseas Chinese in Southeast Asia, has become the language in which much of that area’s international business is transacted. As the power of the West gradually declines relative to that of other civilizations, the use of English and other Western languages in other societies and for communications between societies will also slowly erode. If at some point in the distant future China displaces the West as the dominant civilization in the world, English will give way to Mandarin as the world’s lingua franca.