The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order (8 page)

Read The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order Online

Authors: Samuel P. Huntington

Tags: #Current Affairs, #History, #Modern Civilization, #Non-fiction, #Political Science, #Scholarly/Educational, #World Politics

In the twentieth century the relations among civilizations have thus moved from a phase dominated by the unidirectional impact of one civilization on all others to one of intense, sustained, and multidirectional interactions among all civilizations. Both of the central characteristics of the previous era of intercivilizational relations began to disappear.

First, in the favorite phrases of historians, “the expansion of the West” ended and “the revolt against the West” began. Unevenly and with pauses and reversals, Western power declined relative to the power of other civilizations. The

map

of the world in 1990 bore little resemblance to the

map

of the world in 1920. The balances of military and economic power and of political influence shifted (and will be explored in greater detail in a later

chapter

). The West continued to have significant impacts on other societies, but increasingly the relations between the West and other civilizations were dominated by the reactions of the West to developments in those civilizations. Far from being simply the objects of Western-made history, non-Western societies were increasingly becoming the movers and shapers of their own history and of Western history.

Second, as a result of these developments, the international system expanded beyond the West and became multicivilizational. Simultaneously, conflict among Western states—which had dominated that system for centuries—faded away. By the late twentieth century, the West has moved out of its “warring state” phase of development as a civilization and toward its “universal state” phase. At the end of the century, this phase is still incomplete as the nation states of the West cohere into two semiuniversal states in Europe and North America. These two entities and their constituent units are, however, bound together by an extraordinarily complex network of formal and informal institutional ties. The universal states of previous civilizations are empires. Since democracy, however, is the political form of Western civilization, the emerging universal state of Western civilization is not an empire but rather a compound of federations, confederations, and international regimes and organizations.

The great political ideologies of the twentieth century include liberalism, socialism, anarchism, corporatism, Marxism, communism, social democracy, conservatism, nationalism, fascism, and Christian democracy. They all share one thing in common: they are products of Western civilization. No other

p. 54

civilization has generated a significant political ideology. The West, however, has never generated a major religion. The great religions of the world are all products of non-Western civilizations and, in most cases, antedate Western civilization. As the world moves out of its Western phase, the ideologies which typified late Western civilization decline, and their place is taken by religions and other culturally based forms of identity and commitment. The Westphalian separation of religion and international politics, an idiosyncratic product of Western civilization, is coming to an end, and religion, as Edward Mortimer suggests, is “increasingly likely to intrude into international affairs.”

[32]

The intracivilizational clash of political ideas spawned by the West is being supplanted by an intercivilizational clash of culture and religion.

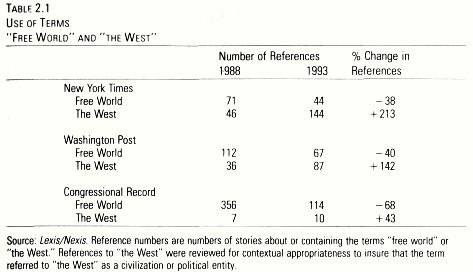

Global political geography thus moved from the one world of 1920 to the three worlds of the 1960s to the more than half-dozen worlds of the 1990s. Concomitantly, the Western global empires of 1920 shrank to the much more limited “Free World” of the 1960s (which included many non-Western states opposed to communism) and then to the still more restricted “West” of the 1990s. This shift was reflected semantically between 1988 and 1993 in the decline in the use of the ideological term “Free World” and the increase in use of the civilizational term “the West” (see

Table 2.1

). It is also seen in increased references to Islam as a cultural-political phenomenon, “Greater China,” Russia and its “near abroad,” and the European Union, all terms with a civilizational content. Intercivilizational relations in this third phase are far more frequent and intense than they were in the first phase and far more equal and reciprocal than they were in the second phase. Also, unlike the Cold War, no single cleavage dominates, and multiple cleavages exist between the West and other civilizations and among the many non-Wests.

Table 2.1 – Use of Terms “Free World” and “The West”

An international system exists, Hedley Bull argued, “when two or more states have sufficient contact between them, and have sufficient impact on one another’s decisions, to cause them to behave—at least in some measure—as parts of a whole.” An international society, however, exists only when states in an international system have “common interests and common values,” “conceive themselves to be bound by a common set of rules,” “share in the working of common institutions,” and have “a common culture or civilization.”

[33]

Like its Sumerian, Greek, Hellenistic, Chinese, Indian, and Islamic predecessors, the European international system of the seventeenth to the nineteenth centuries was also an international society. During the nineteenth and twentieth centuries the European international system expanded to encompass virtually all societies in other civilizations. Some European institutions and practices were also exported to these countries. Yet these societies still lack the common culture that underlay European international society. In terms of British international relations theory, the world is thus a well-developed international system but at best only a very primitive international society.

Every civilization sees itself as the center of the world and writes its history

p. 55

as the central drama of human history. This has been perhaps even more true of the West than of other cultures. Such monocivilizational viewpoints, however, have decreasing relevance and usefulness in a multicivilizational world. Scholars of civilizations have long recognized this truism. In 1918 Spengler denounced the myopic view of history prevailing in the West with its neat division into ancient, medieval, and modern phases relevant only to the West. It is necessary, he said, to replace this “Ptolemaic approach to history” with a Copernican one and to substitute for the “empty figment of one

linear

history, the drama of a

number

of mighty cultures.”

[34]

A few decades later Toynbee castigated the “parochialism and impertinence” of the West manifested in the “egocentric illusions” that the world revolved around it, that there was an “unchanging East,” and that “progress” was inevitable. Like Spengler he had no use for the assumption of the unity of history, the assumption that there is “only one river of civilization, our own, and that all others are either tributary to it or lost in the desert sands.”

[35]

Fifty years after Toynbee, Braudel similarly urged the need to strive for a broader perspective and to understand “the great cultural conflicts in the world, and the multiplicity of its civilizations.”

[36]

The illusions and prejudices of which these scholars warned, however, live on and in the late twentieth century have blossomed forth in the widespread and parochial conceit that the European civilization of the West is now the universal civilization of the world.

Universal Civilization: Meanings

p. 56

S

ome people argue that this era is witnessing the emergence of what V. S. Naipaul called a “universal civilization.”

[1]

What is meant by this term? The idea implies in general the cultural coming together of humanity and the increasing acceptance of common values, beliefs, orientations, practices, and institutions by peoples throughout the world. More specifically, the idea may mean some things which are profound but irrelevant, some which are relevant but not profound, and some which are irrelevant and superficial.

First, human beings in virtually all societies share certain basic values, such as murder is evil, and certain basic institutions, such as some form of the family. Most peoples in most societies have a similar “moral sense,” a “thin” minimal morality of basic concepts of what is right and wrong.

[2]

If this is what is meant by universal civilization, it is both profound and profoundly important, but it is also neither new nor relevant. If people have shared a few fundamental values and institutions throughout history, this may explain some constants in human behavior but it cannot illuminate or explain history, which consists of changes in human behavior. In addition, if a universal civilization common to all humanity exists, what term do we then use to identify the major cultural groupings of humanity short of the human race? Humanity is divided into subgroups—tribes, nations, and broader cultural entities normally called civilizations. If the term civilization is elevated and restricted to what is common to humanity as a whole, either one has to invent a new term to refer to the largest cultural groupings of people short of humanity as a whole or one has to assume

p. 57

that these large but not-humanity-wide groupings evaporate. Vaclav Havel, for example, has argued that “we now live in a single global civilization,” and that this “is no more than a thin veneer” that “covers or conceals the immense variety of cultures, of peoples, of religious worlds, of historical traditions and historically formed attitudes, all of which in a sense lie ‘beneath’ it.”

[3]

Only semantic confusion, however, is gained by restricting “civilization” to the global level and designating as “cultures” or “subcivilizations,” those largest cultural entities which have historically always been called civilizations.

[F04]

Second, the term “universal civilization” could be used to refer to what civilized societies have in common, such as cities and literacy, which distinguish them from primitive societies and barbarians. This is, of course, the eighteenth century singular meaning of the term, and in this sense a universal civilization is emerging, much to the horror of various anthropologists and others who view with dismay the disappearance of primitive peoples. Civilization in this sense has been gradually expanding throughout human history, and the spread of civilization in the singular has been quite compatible with the existence of many civilizations in the plural.

Third, the term “universal civilization” may refer to the assumptions, values, and doctrines currently held by many people in Western civilization and by some people in other civilizations. This might be called the Davos Culture. Each year about a thousand businessmen, bankers, government officials, intellectuals, and journalists from scores of countries meet in the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland. Almost all these people hold university degrees in the physical sciences, social sciences, business, or law, work with words and/or numbers, are reasonably fluent in English, are employed by governments, corporations, and academic institutions with extensive international involvements, and travel frequently outside their own country. They generally share beliefs in individualism, market economies, and political democracy, which are also common among people in Western civilization. Davos people control virtually all international institutions, many of the world’s governments, and the bulk of the world’s economic and military capabilities. The Davos Culture hence is tremendously important. Worldwide, however, how many people share this culture? Outside the West, it is probably shared by less than 50 million people or 1 percent of the world’s population and perhaps by as few as one-tenth of 1 percent of the world’s population. It is far from a universal culture, and the leaders who share in the Davos Culture do not necessarily

p. 58

have a secure grip on power in their own societies. This “common intellectual culture exists,” as Hedley Bull pointed out, “only at the elite level: its roots are shallow in many societies . . . [and] it is doubtful whether, even at the diplomatic level, it embraces what was called a common moral culture or set of common values, as distinct from a common intellectual culture.”

[4]

Fourth, the idea is advanced that the spread of Western consumption patterns and popular culture around the world is creating a universal civilization. This argument is neither profound nor relevant. Cultural fads have been transmitted from civilization to civilization throughout history. Innovations in one civilization are regularly taken up by other civilizations. These are, however, either techniques lacking in significant cultural consequences or fads that come and go without altering the underlying culture of the recipient civilization. These imports “take” in the recipient civilization either because they are exotic or because they are imposed. In previous centuries the Western world was periodically swept by enthusiasms for various items of Chinese or Hindu culture. In the nineteenth century cultural imports from the West became popular in China and India because they seemed to reflect Western power. The argument now that the spread of pop culture and consumer goods around the world represents the triumph of Western civilization trivializes Western culture. The essence of Western civilization is the Magna Carta, not the Magna Mac. The fact that non-Westerners may bite into the latter has no implications for their accepting the former.