The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order (10 page)

Read The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order Online

Authors: Samuel P. Huntington

Tags: #Current Affairs, #History, #Modern Civilization, #Non-fiction, #Political Science, #Scholarly/Educational, #World Politics

As the former colonies moved toward independence and became independent, promotion or use of the indigenous languages and suppression of the languages of empire was one way for nationalist elites to distinguish themselves from the Western colonialists and to define their own identity. Following independence, however, the elites of these societies needed to distinguish themselves from the common people of their societies. Fluency in English, French, or another Western language did this. As a result, elites of non-Western societies are often better able to communicate with Westerners and each other than with the people of their own society (a situation like that in the West in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries when aristocrats from different countries could easily communicate in French with each other but could not speak the vernacular of their own country). In non-Western societies two opposing trends appear to be underway. On the one hand, English is increasingly used at the university level to equip graduates to function effectively in the global competition for capital and customers. On the other hand, social and political pressures increasingly lead to the more general use of indigenous languages, Arabic displacing French in North Africa, Urdu supplanting English as the language of government and education in Pakistan, and indigenous language media replacing English media in India. This development was foreseen by the Indian

p. 64

Education Commission in 1948, when it argued that “use of English . . . divides the people into two nations, the few who govern and the many who are governed, the one unable to talk the language of the other, and mutually uncomprehending.” Forty years later the persistence of English as the elite language bore out this prediction and had created “an unnatural situation in a working democracy based on adult suffrage. . . . English-speaking India and politically-conscious India diverge more and more” stimulating “tensions between the minority at the top who know English, and the many millions—armed with the vote—who do not.”

[17]

To the extent that non-Western societies establish democratic institutions and the people in those societies participate more extensively in government, the use of Western languages declines and indigenous languages become more prevalent.

The end of the Soviet empire and of the Cold War promoted the proliferation and rejuvenation of languages which had been suppressed or forgotten. Major efforts have been underway in most of the former Soviet republics to revive their traditional languages. Estonian, Latvian, Lithuanian, Ukrainian, Georgian, and Armenian are now the national languages of independent states. Among the Muslim republics similar linguistic assertion has occurred, and Azerbaijan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan have shifted from the Cyrillic script of their former Russian masters to the Western script of their Turkish kinsmen, while Persian-speaking Tajikistan has adopted Arabic script. The Serbs, on the other hand, now call their language Serbian rather than Serbo-Croatian and have shifted from the Western script of their Catholic enemies to the Cyrillic script of their Russian kinsmen. In parallel moves, the Croats now call their language Croatian and are attempting to purge it of Turkish and other foreign words, while the same “Turkish and Arabic borrowings, linguistic sediment left by the Ottoman Empire’s 450-year presence in the Balkans, have come back into vogue” in Bosnia.

[18]

Language is realigned and reconstructed to accord with the identities and contours of civilizations. As power diffuses Babelization spreads.

A universal religion is only slightly more likely to emerge than is a universal language. The late twentieth century has seen a global resurgence of religions around the world (see pp.

95

-

101

). That resurgence has involved the intensification of religious consciousness and the rise of fundamentalist movements. It has thus reinforced the differences among religions. It has not necessarily involved significant shifts in the proportions of the world’s population adhering to different religions. The data available on religious adherents are even more fragmentary and unreliable than the data available on language speakers.

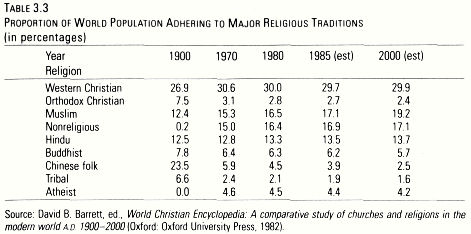

Table 3.3

sets out figures derived from one widely used source. These and other data suggest that the relative numerical strength of religions around the world has not changed dramatically in this century. The largest change recorded by this source was the increase in the proportion of people classified

p. 65

as “nonreligious” and “atheist” from 0.2 percent in 1900 to 20.9 percent in 1980. Conceivably this could reflect a major shift away from religion, and in 1980 the religious resurgence was just gathering steam. Yet this 20.7 percent increase in nonbelievers is closely matched by a 19.0 percent decrease in those classified as adherents of “Chinese folk-religions” from 23.5 percent in 1900 to 4.5 percent in 1980. These virtually equal increases and decreases suggest that with the advent of communism the bulk of China’s population was simply reclassified from folk-religionist to nonbelieving.

Table 3.3 – Proportion of World Population Adhering to Major Religious Traditions

The data do show increases in the proportions of the world population adhering to the two major proselytizing religions, Islam and Christianity, over eighty years. Western Christians were estimated at 26.9 percent of the world’s population in 1900 and 30 percent in 1980. Muslims increased more dramatically from 12.4 percent in 1900 to 16.5 percent or by other estimates 18 percent in 1980. During the last decades of the twentieth century both Islam and Christianity significantly expanded their numbers in Africa, and a major shift toward Christianity occurred in South Korea. In rapidly modernizing societies, if the traditional religion is unable to adapt to the requirements of modernization, the potential exists for the spread of Western Christianity and Islam. In these societies the most successful protagonists of Western culture are not neo-classical economists or crusading democrats or multinational corporation executives. They are and most likely will continue to be Christian missionaries. Neither Adam Smith nor Thomas Jefferson will meet the psychological, emotional, moral, and social needs of urban migrants and first-generation secondary school graduates. Jesus Christ may not meet them either, but He is likely to have a better chance.

In the long run, however, Mohammed wins out. Christianity spreads primarily by conversion, Islam by conversion and reproduction. The percentage of Christians in the world peaked at about 30 percent in the 1980s, leveled off, is

p. 66

now declining, and will probably approximate about 25 percent of the world’s population by 2025. As a result of their extremely high rates of population growth (see

chapter 5

), the proportion of Muslims in the world will continue to increase dramatically, amounting to 20 percent of the world’s population about the turn of the century, surpassing the number of Christians some years later, and probably accounting for about 30 percent of the world’s population by 2025.

[19]

The concept of a universal civilization is a distinctive product of Western civilization. In the nineteenth century the idea of “the white man’s burden” helped justify the extension of Western political and economic domination over non-Western societies. At the end of the twentieth century the concept of a universal civilization helps justify Western cultural dominance of other societies and the need for those societies to ape Western practices and institutions. Universalism is the ideology of the West for confrontations with non-Western cultures. As is often the case with marginals or converts, among the most enthusiastic proponents of the single civilization idea are intellectual migrants to the West, such as Naipaul and Fouad Ajami, for whom the concept provides a highly satisfying answer to the central question: Who am I? “White man’s nigger,” however, is the term one Arab intellectual applied to these migrants,

[20]

and the idea of a universal civilization finds little support in other civilizations. The non-Wests see as Western what the West sees as universal. What Westerners herald as benign global integration, such as the proliferation of worldwide media, non-Westerners denounce as nefarious Western imperialism. To the extent that non-Westerners see the world as one, they see it as a threat.

The arguments that some sort of universal civilization is emerging rest on one or more of three assumptions as to why this should be the case. First, there is the assumption, discussed in

chapter 1

, that the collapse of Soviet communism meant the end of history and the universal victory of liberal democracy throughout the world. This argument suffers from the single alternative fallacy. It is rooted in the Cold War perspective that the only alternative to communism is liberal democracy and that the demise of the first produces the universality of the second. Obviously, however, there are many forms of authoritarianism, nationalism, corporatism, and market communism (as in China) that are alive and well in today’s world. More significantly, there are all the religious alternatives that lie outside the world of secular ideologies. In the modern world, religion is a central, perhaps

the

central, force that motivates and mobilizes people. It is sheer hubris to think that because Soviet communism has collapsed, the West has won the world for all time and that Muslims, Chinese, Indians, and others are going to rush to embrace Western liberalism as the only alternative. The Cold War division of humanity is over. The more fundamental

p. 67

divisions of humanity in terms of ethnicity, religions, and civilizations remain and spawn new conflicts.

Second, there is the assumption that increased interaction among peoples—trade, investment, tourism, media, electronic communication generally—is generating a common world culture. Improvements in transportation and communications technology have indeed made it easier and cheaper to move money, goods, people, knowledge, ideas, and images around the world. No doubt exists as to the increased international traffic in these items. Much doubt exists, however, as to the impact of this increased traffic. Does trade increase or decrease the likelihood of conflict? The assumption that it reduces the probability of war between nations is, at a minimum, not proven, and much evidence exists to the contrary. International trade expanded significantly in the 1960s and 1970s and in the following decade the Cold War came to an end. In 1913, however, international trade was at record highs and in the next few years nations slaughtered each other in unprecedented numbers.

[21]

If international commerce at that level could not prevent war, when can it? The evidence simply does not support the liberal, internationalist assumption that commerce promotes peace. Analyses done in the 1990s throw that assumption further into question. One study concludes that “increasing levels of trade may be a highly divisive force . . . for international politics” and that “increasing trade in the international system is, by itself, unlikely to ease international tensions or promote greater international stability.”

[22]

Another study argues that high levels of economic interdependence “can be either peace-inducing

or

war-inducing, depending on the expectations of future trade.” Economic interdependence fosters peace only “when states expect that high trade levels will continue into the foreseeable future.” If states do not expect high levels of interdependence to continue, war is likely to result.

[23]

The failure of trade and communications to produce peace or common feeling is consonant with the findings of social science. In social psychology, distinctiveness theory holds that people define themselves by what makes them different from others in a particular context: “one perceives oneself in terms of characteristics that distinguish oneself from other humans, especially from people in one’s usual social milieu . . . a woman psychologist in the company of a dozen women who work at other occupations thinks of herself as a psychologist; when with a dozen male psychologists, she thinks of herself as a woman.”

[24]

People define their identity by what they are not. As increased communications, trade, and travel multiply the interactions among civilizations, people increasingly accord greater relevance to their civilizational identity. Two Europeans, one German and one French, interacting with each other will identify each other as German and French. Two Europeans, one German and one French, interacting with two Arabs, one Saudi and one Egyptian, will define themselves as Europeans and Arabs. North African immigration to France generates hostility among the French and at the same time increased

p. 68

receptivity to immigration by European Catholic Poles. Americans react far more negatively to Japanese investment than to larger investments from Canada and European countries. Similarly, as Donald Horowitz has pointed out, “An Ibo may be . . . an Owerri Ibo or an Onitsha Ibo in what was the Eastern region of Nigeria. In Lagos, he is simply an Ibo. In London, he is Nigerian. In New York, he is an African.”

[25]

From sociology, globalization theory produces a similar conclusion: “in an increasingly globalized world—characterized by historically exceptional degrees of civilizational, societal and other modes of interdependence and widespread consciousness thereof—there is an

exacerbation

of civilizational, societal and ethnic self-consciousness.” The global religious revival, “the return to the sacred,” is a response to people’s perception of the world as “a single place.”

[26]