The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order (21 page)

Read The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order Online

Authors: Samuel P. Huntington

Tags: #Current Affairs, #History, #Modern Civilization, #Non-fiction, #Political Science, #Scholarly/Educational, #World Politics

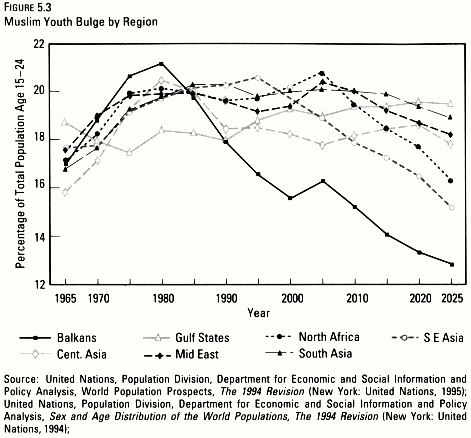

Figure 5.3 – Muslim Youth Bulge by Region

No society can sustain double digit economic growth indefinitely, and the Asian economic boom will level off sometime in the early twenty-first century. The rates of Japanese economic growth dropped substantially in the mid-1970s and afterwards were not significantly higher than those of the United States and European countries. One by one other Asian “economic miracle” states will see their growth rates decline and approximate the “normal” levels maintained in complex economies. Similarly, no religious revival or cultural movement lasts indefinitely, and at some point the Islamic Resurgence will subside and fade into history. That is most likely to happen when the demographic impulse powering it weakens in the second and third decades of the twenty-first century. At that time, the ranks of militants, warriors, and migrants will dimin

p. 121

ish, and the high levels of conflict within Islam and between Muslims and others (see

chapter 10

) are likely to decline. The relations between Islam and the West will not become close but they will become less conflictual, and quasi war (see

chapter 9

) is likely to give way to cold war or perhaps even cold peace.

Economic development in Asia will leave a legacy of wealthier, more complex economies, with substantial international involvements, prosperous bourgeoisies, and well-off middle classes. These are likely to lead towards more pluralistic and possibly more democratic politics, which will not necessarily, however, be more pro-Western. Enhanced power will instead promote continued Asian assertiveness in international affairs and efforts to direct global trends in ways uncongenial to the West and to reshape international institutions away from Western models and norms. The Islamic Resurgence, like comparable movements including the Reformation, will also leave important legacies. Muslims will have a much greater awareness of what they have in common and what distinguishes them from non-Muslims. The new generation of leaders that take over as the youth bulge ages will not necessarily be fundamentalist but will be much more committed to Islam than their predecessors. Indigenization will be reinforced. The Resurgence will leave a network of Islamist social, cultural, economic, and political organizations within societies and transcending societies. The Resurgence will also have shown that “Islam is the solution” to the problems of morality, identity, meaning, and faith, but not to the problems of social injustice, political repression, economic backwardness, and military weakness. These failures could generate widespread disillusionment with political Islam, a reaction against it, and a search for alternative “solutions” to these problems. Conceivably even more intensely anti-Western nationalisms could emerge, blaming the West for the failures of Islam. Alternatively, if Malaysia and Indonesia continue their economic progress, they might provide an “Islamic model” for development to compete with the Western and Asian models.

In any event, during the coming decades Asian economic growth will have deeply destabilizing effects on the Western-dominated established international order, with the development of China, if it continues, producing a massive shift in power among civilizations. In addition, India could move into rapid economic development and emerge as a major contender for influence in world affairs. Meanwhile Muslim population growth will be a destabilizing force for both Muslim societies and their neighbors. The large numbers of young people with secondary educations will continue to power the Islamic Resurgence and promote Muslim militancy, militarism, and migration. As a result, the early years of the twenty-first century are likely to see an ongoing resurgence of non-Western power and culture and the clash of the peoples of non-Western civilizations with the West and with each other.

Chapter 6 – The Cultural Reconfiguration of Global Politics

Groping For Groupings: The Politics Of Identity

p. 125

S

purred by modernization, global politics is being reconfigured along cultural lines. Peoples and countries with similar cultures are coming together. Peoples and countries with different cultures are coming apart. Alignments defined by ideology and superpower relations are giving way to alignments defined by culture and civilization. Political boundaries increasingly are redrawn to coincide with cultural ones: ethnic, religious, and civilizational. Cultural communities are replacing Cold War blocs, and the fault lines between civilizations are becoming the central lines of conflict in global politics.

During the Cold War a country could be nonaligned, as many were, or it could, as some did, change its alignment from one side to another. The leaders of a country could make these choices in terms of their perceptions of their security interests, their calculations of the balance of power, and their ideological preferences. In the new world, however, cultural identity is the central factor shaping a country’s associations and antagonisms. While a country could avoid Cold War alignment, it cannot lack an identity. The question, “Which side are you on?” has been replaced by the much more fundamental one, “Who are you?” Every state has to have an answer. That answer, its cultural identity, defines the state’s place in world politics, its friends, and its enemies.

The 1990s have seen the eruption of a global identity crisis. Almost everywhere one looks, people have been asking, “Who are we?” “Where do we belong?” and “Who is not us?” These questions are central not only to peoples attempting to forge new nation states, as in the former Yugoslavia, but also

p. 126

much more generally. In the mid-1990s the countries where questions of national identity were actively debated included, among others: Algeria, Canada, China, Germany, Great Britain, India, Iran, Japan, Mexico, Morocco, Russia, South Africa, Syria, Tunisia, Turkey, Ukraine, and the United States. Identity issues are, of course, particularly intense in cleft countries that have sizable groups of people from different civilizations.

In coping with identity crisis, what counts for people are blood and belief, faith and family. People rally to those with similar ancestry, religion, language, values, and institutions and distance themselves from those with different ones. In Europe, Austria, Finland, and Sweden, culturally part of the West, had to be divorced from the West and neutral during the Cold War; they are now able to join their cultural kin in the European Union. The Catholic and Protestant countries in the former Warsaw Pact, Poland, Hungary, the Czech Republic, and Slovakia, are moving toward membership in the Union and in NATO, and the Baltic states are in line behind them. The European powers make it clear that they do not want a Muslim state, Turkey, in the European Union and are not happy about having a second Muslim state, Bosnia, on the European continent. In the north, the end of the Soviet Union stimulates the emergence of new (and old) patterns of association among the Baltic republics and between them, Sweden, and Finland. Sweden’s prime minister pointedly reminds Russia that the Baltic republics are part of Sweden’s “near abroad” and that Sweden could not be neutral in the event of Russian aggression against them.

Similar realignments occur in the Balkans. During the Cold War, Greece and Turkey were in NATO, Bulgaria and Romania were in the Warsaw Pact, Yugoslavia was nonaligned, and Albania was an isolated sometime associate of communist China. Now these Cold War alignments are giving way to civilizational ones rooted in Islam and Orthodoxy. Balkan leaders talk of crystallizing a Greek-Serb-Bulgarian Orthodox alliance. The “Balkan wars,” Greece’s prime minister alleges, “. . . have brought to the surface the resonance of Orthodox ties. . . . this is a bond. It was dormant, but with the developments in the Balkans, it is taking on some real substance. In a very fluid world, people are seeking identity and security. People are looking for roots and connections to defend themselves against the unknown.” These views were echoed by the leader of the principal opposition party in Serbia: “The situation in southeastern Europe will soon require the formation of a new Balkan alliance of Orthodox countries, including Serbia, Bulgaria, and Greece, in order to resist the encroachment of Islam.” Looking northward, Orthodox Serbia and Romania cooperate closely in dealing with their common problems with Catholic Hungary. With the disappearance of the Soviet threat, the “unnatural” alliance between Greece and Turkey becomes essentially meaningless, as conflicts intensify between them over the Aegean Sea, Cyprus, their military balance, their roles in NATO and the European Union, and their relations with the United States. Turkey reasserts its role as the protector of Balkan Muslims and provides

p. 127

support to Bosnia. In the former Yugoslavia, Russia backs Orthodox Serbia, Germany promotes Catholic Croatia, Muslim countries rally to the support of the Bosnian government, and the Serbs fight Croatians, Bosnian Muslims, and Albanian Muslims. Overall, the Balkans have once again been Balkanized along the religious lines. “Two axes are emerging,” as Misha Glenny observed, “one dressed in the garb of Eastern Orthodoxy, one veiled in Islamic raiment” and the possibility exists of “an ever-greater struggle for influence between the Belgrade/Athens axis and the Albanian/Turkish alliance.”

[1]

Meanwhile in the former Soviet Union, Orthodox Belarus, Moldova, and Ukraine gravitate toward Russia, and Armenians and Azeris fight each other while their Russian and Turkish kin attempt both to support them and to contain the conflict. The Russian army fights Muslim fundamentalists in Tajikistan and Muslim nationalists in Chechnya. The Muslim former Soviet republics work to develop various forms of economic and political association among themselves and to expand their ties with their Muslim neighbors, while Turkey, Iran, and Saudi Arabia devote great effort to cultivating relations with these new states. In the Subcontinent, India and Pakistan remain at loggerheads over Kashmir and the military balance between them, fighting in Kashmir intensifies, and within India, new conflicts arise between Muslim and Hindu fundamentalists.

In East Asia, home to people of six different civilizations, arms buildups gain momentum and territorial disputes come to the fore. The three lesser Chinas, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Singapore, and the overseas Chinese communities in Southeast Asia become increasingly oriented toward, involved in, and dependent on the mainland. The two Koreas move hesitatingly but meaningfully toward unification. The relations in Southeast Asian states between Muslims, on the one hand, and Chinese and Christians, on the other, become increasingly tense and at times violent.

In Latin America, economic associations—Mercosur, the Andean Pact, the tripartite pact (Mexico, Colombia, Venezuela), the Central American Common Market—take on a new life, reaffirming the point demonstrated most graphically by the European Union that economic integration proceeds faster and further when it is based on cultural commonality. At the same time, the United States and Canada attempt to absorb Mexico into the North American Free Trade Area in a process whose long-term success depends largely on the ability of Mexico to redefine itself culturally from Latin American to North American.

With the end of the Cold War order, countries throughout the world began developing new and reinvigorating old antagonisms and affiliations. They have been groping for groupings, and they are finding those groupings with countries of similar culture and the same civilization. Politicians invoke and publics identify with “greater” cultural communities that transcend nation state boundaries, including “Greater Serbia,” “Greater China,” “Greater Turkey,” “Greater

p. 128

Hungary,” “Greater Croatia,” “Greater Azerbaijan,” “Greater Russia,” “Greater Albania,” “Greater Iran,” and “Greater Uzbekistan.”

Will political and economic alignments always coincide with those of culture and civilization? Of course not. Balance of power considerations will at times lead to cross-civilizational alliances, as they did when Francis I joined with the Ottomans against the Hapsburgs. In addition, patterns of association formed to serve the purposes of states in one era will persist into a new era. They are, however, likely to become weaker and less meaningful and to be adapted to serve the purposes of the new age. Greece and Turkey will undoubtedly remain members of NATO but their ties to other NATO states are likely to attenuate. So also are the alliances of the United States with Japan and Korea, its de facto alliance with Israel, and its security ties with Pakistan. Multicivilizational international organizations like ASEAN could face increasing difficulty in maintaining their coherence. Countries such as India and Pakistan, partners of different superpowers during the Cold War, now redefine their interests and seek new associations reflecting the realities of cultural politics. African countries which were dependent on Western support designed to counter Soviet influence look increasingly to South Africa for leadership and succor.

Why should cultural commonality facilitate cooperation and cohesion among people and cultural differences promote cleavages and conflicts?