Postcards (18 page)

Authors: Annie Proulx

‘I want to learn to drive, Ronnie,’ said Jewell. ‘How do I go about it? There’s the car out there and it should run. I’m determined to learn.’

‘I’d as soon teach you, Jewell. No sense to pay somebody when you got neighbors. It’s a good idea. Let you get out. I’ll take the batt’ry along with me today and get it charged up. You know, they’re talking about hiring at the cannery. I’ve heard they’ll take on older women. I don’t know as you’d care for that kind of work, but you could drive back and forth. Look into it, anyway.’ His relief warmed the room. An old woman neighbor could be a terrible burden. But if she had something coming in …

‘You’ll need the telephone, Jewell. I’ll call them up, get them to send somebody out.’

‘If you knew how many times I wished I knew how to drive. It would have made some difference if I could of gone out and got some work years ago, but Mink wouldn’t hear of it. Had a fit every time I wanted to go somewhere.’ Remembering Ott’s wife’s card party and how they argued about it for days. Mink had worn his outrage to bed like a nightshirt, but for once she’d spoken up to him.

‘Well, I don’t care how you bunch your mouth up and bite your words into specks, I’m goin’ to that card party. Think you’d be glad about it, your own brother’s wife gives a card party.’ Whispering fiercely in the dark. They’d had the habit of whispering in bed since Loyal was a baby.

Mink rolled his head on the fiat pillow, whispered back. ‘Why the hell should I be glad? And what the hell’s that got to do with the price of beans, who’s givin’ it? Must be nice, go traipsin’ off to a party on Saturday afternoon, the hell with the work, just go have a good time. You don’t even know how to play no card games. Expect me to drop everything and drive you over there, set around, bring you back. Wish

I

could just skip the chores and go off and have a good time—’ He rummaged around for an example of a frivolous good time. ‘—Go to hell off and go bowlin’.’

She’d smothered her laugh at the idea of Mink, standing grim in

his manure-caked barn boots in a bowling alley, the ball like a bomb in his knotted hands. She’d choked on the idea. Her shoulders heaved, she buried her face in the pillow.

‘Goddamn it, you feel that bad about it, go ahead and go! Christ sake, you don’t have to bawl about it. Go on! Who’s stoppin’ you?’ But she could not quit. That he mistook her laughter for sobs made it even richer. Mink bowling. Her blubbering, because she couldn’t go to a stupid old card party.

‘Oh, oh, oh,’ she moaned, ‘I haven’t laughed like that.’

He sighed, the bitter huff of a man whose patience is eroded, ‘I know where Dub gets his fool ways.’

She was almost asleep when he whispered again. ‘How are you goin’ to get over and back? I can’t take time off the milkin’ chores.’

‘Ride over with Mrs. Nipple. Ronnie’s takin’ her. Loyal could pick us up, save Ronnie a second trip. He’s got cows, too, you know. At five o’clock. It’s from one to five. I’m goin’ to start the supper in the mornin’, a good chicken stew or something, so it’ll be quick to get up when I come back.’

‘I suppose we got to do it.’

She was gone and snoring, only half conscious of the warmth of him, his hard arm around her waist, pulling her up tight to him, fitting his jackknifed knees in behind hers …

‘What about Mernelle? Be good if Mernelle learned.’ Ronnie, still harping on about learning to drive brought her back.

‘I doubt she’ll be interested. Mernelle has got something up her sleeve. Not telling me a thing. I don’t know what it is, but she spends half her time up in her room, half over to Darlene’s, and the other half up at the mailbox waiting for the Rural Free Delivery. She took what happened hard. Quit school when they come for Mink. Since he passed on she hardly says anything. She’s not sharin’ any secrets with me.’

Eight days since she sent the letter, too soon for an answer, she knew, but she couldn’t help thinking he would feel some special quality about her letter even while it was still in the envelope. Hundreds of girls

would probably write to him, and it would take time to sort through all that mail, even if he had help. She knew he would do it alone. He was used to doing things alone.

It had been on the front page of two newspapers, maybe even more. The story was written in a jokey way that tried to make a fool out of him. But she saw around that stuff.

‘Lonely Hearts Prisoner’ Advertises for Wife.

Ray MacWay, a 19-year-old lumber grader at Fredette’s Building Supplies in Burlington, walked into the

Trumpet

editorial room and said he wanted to advertise for a wife. ‘I want someone who’s lonely like me. I’ve been an orphan since I was young and I live alone in a furnished room. It’s hard for me to meet any girls because of my work hours. I call myself the lonely hearts prisoner. I went to work when I was around six years old peeling pulp in the woods. I ran off when I was 16, been all around, to Maine, up to Canada, to Mexico and Texas. But this is my home state. I’m a good worker. I feel there’s a young lady out there lonely like me that we could be happy together. I hope she’ll write me in care of the

Trumpet.’

The photograph next to the story showed a young man with ragged hair standing by a pile of lumber. The lake spread out in the background. There were holes in his trouser knees. He wore a checked jacket and Mernelle could see the raveled cuffs. His face looked plain, but calm. Even in the cramped ink dots of the newspaper photo he had the lonesome look. She saw enough of it in the mirror to know.

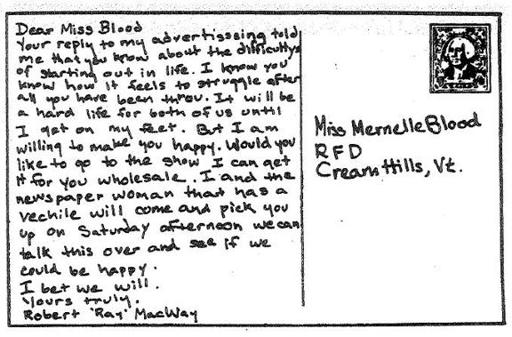

The answer came on a Thursday morning. It was still raining, a steady sluice that gullied the driveway. She walked down, her black oilcloth raincoat cracked open from breast to shin like the wings of a beetle readying itself to fly. Her boot heels threw specks of muddy gravel onto her calves. The postcard showed a view of Red Rocks Point jutting out into Lake Champlain. The message space was filled with small printing, very legible despite the spelling errors. As serious as her own letter had been. The alders behind the mailbox were blackly wet, cracking the sky.

At nine o’clock on Saturday morning Mernelle was drying the cereal bowls and thinking what to say to Jewell. The sink gave off its odor. She might say ‘I am getting away from the sink.’ Or, ‘What am I supposed to do, rot here in this place?’ Her clothes were ready. The blue skirt, a deep violet blue that had hardly faded from hanging on the line, and the white blouse with the buttons shaped like tiny pearl hearts. She had a lemon put aside; when she washed her hair, lemon juice in the rinse water would give it a red tone. ‘“Little spitfire,”’ she whispered to herself, thinking of some movie. She could say ‘You and Da lived like pigs. I want a nice place like Mrs. Weedmeyer’s that fixed up the Batchelder dump. A shower with a glass door. Carpets. Silverware with roses on the handles and matching plates with blue rims and a golden stripe.’

It was already too complicated to explain to Jewell, to say it so Jewell would see she had to get away no matter how. It all boiled down to two stupid sentences, that she was going off with somebody she didn’t know, and it was somebody who’d advertised in the paper for a wife. She could hear Jewell’s dust mop on the stairs, and hear a truck straining up the hill. Uncle Ott bringing more machinery or equipment for his new property. He’d brought over a bulldozer two

days earlier, a hulking mud-covered thing that made a noise like turkeys when it started up. It rolled down off the truck bed and stood huffing in the field of dandelions of the same matching yellow, in the coarse new grass.

‘I’d like to know what he thinks he’s going to do with that,’ said Jewell. ‘He says he wants to plant corn. I never see a farmer use a bulldozer for a plow or a seeder. Loyal would have a fit to see that thing in his field.’

The heavy idling echoed from the dooryard, there were steps on the porch and a knock. Not Ott, after all, who’d opened the door all his life.

‘Hello. I’m looking for Mernelle Blood.’ A steady voice, wired with doggedness.

She could hear Jewell’s dust mop pause on the stairs. The heat of the May morning struck through the screen door, the smell of grass and white blossom pressing in past the figure on the other side of the screen. She recognized his stance from the newspaper photograph. A flow of air drifted into the kitchen, filled it with the scent of mock orange, the sour exhaust of the stuttering car in the yard. Through the screen she could see knots of flies hovering at the tips of the pin cherry branches, the curve of blue metal.

‘Oh God, I’m not ready. I haven’t washed my hair.’

‘I couldn’t wait until the afternoon,’ he said. ‘I couldn’t wait.’ The screen door rattled faintly under his trembling hand.

Jewell, listening on the stairs, guessed at most of it.

HE HELD OPEN the car door for her and she slid in behind the driver, a heavyset woman with cascades of curly grey hair sweeping down her back and wet eyes the color of tea.

‘This is Mrs. Greenslit. She’s the reporter for the

Trumpet

that wrote the story.’

‘Just call me Arlene. Yep, this is my story and I’m sticking with it. You two kids are the guests of the

Trumpet —

within reason. That includes dinner and a movie tonight and Miss Blood, you don’t mind if I call you Mernelle, do you, you can stay over at my place free of charge until you kids see how this thing is gonna go. The only people there are me and my husband Pearl and Pearl’s brother Ruby.

They don’t care if I bring home the bald-headed sword swallower. It’s all in the day’s work for a reporter. Oh, the stories I covered Mernelle you wouldn’t believe. I was telling Ray here while we were waiting for you about last year when this amazing truck driver with no arms, drove with his feet, rolled into town and I rode with him all the way up to Montreal. Caught the train back. He was just wonderful how he could manage, steer and everything. He stayed over too. Slept in the same bed you’re gonna sleep in. I did a big Human Interest story on him. That’s my specialty, Human Interest. So this story, the story of you two kiddies, is a natural for me. Oh yes, I seen it all. This is nothing. From my own life and everything else. I just naturally run into these stories. I was born in New York state, but came across the lake with my family when I was three. Grew up in Rouses Point. My father was a heavy drinker. You know, when he died my mother had his tombstone made over in Barre in the shape of a whiskey bottle. Six feet high. I went back to show it to some people I know a couple of years ago and somebody had stolen it. So I did a feature story on it, “The Stolen Tombstone” and the paper got a tip that a certain gentleman down in Amherst, Massachusetts, a college professor, was using it for a coffee table. The police got it back for us. The Massachusetts police. Of course we had to go down there with a flatbed truck and pick it up. My husband had a few choice words for the college professor. I wouldn’t repeat them. You can’t push Pearl around. The thing that surprised me was it had been gone a couple of years and my mother didn’t even know it. And how did he get it down there? He would not say, but denied it was a truck. I did a story on a bat-shoot. Know what that is? Well, I guess you don’t read the

Trumpet,

because it was one of the most popular stories they ever ran. I don’t know how many letters they got on that story. It was about this hunting and fishing club and how they wanted to shoot clay pigeons on the weekend, but they couldn’t get ’em, just couldn’t get ’em here, so this one guy has bats in his attic, see, and he goes and gets them in the daytime when they’re sleeping, puts them in this box, pokes holes in it so they can breathe, and then brings it to the club. They let the bats go and that’s what they shot since they couldn’t get the clay pigeons. They stopped though when there

was a man wounded. The bats flew low. You know Mr. File, Fred File, that’s the editor of the

Trumpet

thought you kids might want to go out dancing after the movie – dinner at Bove’s, Italian, all you can eat, the lasagna is great, then the movie, I forgot what’s playing, oh no, I remember, it’s

I Can Get It For You Wholesale

with Irene Dunne or somebody. A comedy, supposed to be hilarious. But the dancing, there isn’t any tonight so you might just have to walk around. Stroll. The important thing is to get to know each other. I was telling Ray here on the way over, that’s the most important thing in the world, getting to know another person, and probably the hardest thing, too. One of the best stories I ever did was about this guy who fell in love with a friend of his mother’s, she was, I don’t know, maybe twenty-five years older than him, had white hair and all, but he was crazy about her. Of course the only thing he knew about her was what he saw when she came to visit his mother. She was always very nice and I guess that’s what he liked. His mother drank, I think, and wasn’t too kind to him. So one day this friend of his mother comes in and he gets down on his knees in front of her and says “I love you,” and she thinks he’s flipped his wig, she gets up and starts to go into the kitchen to get his mother, and he grabs her and she shoves him so he goes in his bedroom and gets a gun and comes out and says “If I can’t have you nobody can” and shoots her. Shoots her dead. And the mother’s in the kitchen through all this stirring up iced tea. So the point is to get to know somebody as well as you can before you drag them off. Right, Ray?’