Postcards (33 page)

Authors: Annie Proulx

He pulled into the driveway, aligning the wheels with the sloping strips of concrete on each side of the tufted ridge of grass that brushed

the underside of the car. He could see the red of the kitchen curtain through the window, see Mernelle moving around the table, probably smoothing out the place mats or laying the silver out in short rows like children lined up for a photograph.

The door had swelled in the dampness and he had to push it twice before it would open. Mernelle, her rump to him in the tight black pants as she bent and reached into the cupboard under the sink for a fresh sponge said ‘Nasty out?’

‘Pretty bad. Getting colder already. They’re calling for it to snow before morning.’

‘The deer hunters will be glad.’ The wind smashed rain against the back door. The gas tank cover rattled against the house.

‘Yeah, they’ll like it. How long to supper? Smells incredible good. What is it?’

‘Roast pork with baked squash. Seemed like a good idea with this bad weather. And I made apple pie. That’s what you smell, the cinnamon.’

‘You want a drink?’ Hung his damp coat on the wall hook where it could dry. From him came the bitter fragrance of raw wood. His slippers were in the hall.

‘Maybe one. Make it light.’ She peered into the hot oven, jabbing at the pork with the meat fork. Ray turned on the little radio over the sink. Trumpet music, something Latin American with a clicking sound. He took the bottle of bourbon out of the sugar cupboard with its smell of dry pine and spices, the green ginger ale bottle from the refrigerator. Mernelle pulled the ice cube tray out of the freezer.

‘I just filled it this morning,’ she said, ‘so the ice cubes don’t have that old taste.’ She held the tray under running water until the lever cracked the cubes loose with a brief icy groan. Ray stood behind her, leaning against her, pressing her belly against the edge of the sink. He breathed into her hair. She felt the heat of his breath on her scalp, in her ear, felt his mouth at the nape of her neck, his tongue licking the stray hairs.

‘Ah. Ah,’ he said. ‘Home. I love it.’

Her blighted longing for kids flickered. ‘Want to give that roast another fifteen minutes. It’s five pounds so we’ll have enough leftovers

to make shepherd’s pie tomorrow.’ She took her drink from him. The glass was cold in her hand. The ice knocked glassily.

In the living room Ray sat in his leatherette recliner, Mernelle on the sofa rich in its gold tweed upholstery, tapered legs stabbing into the shag carpet. The coffee table, of sleek caramel wood, bore a lustrous dish of mints, stacked copies of

Lumberyard Review, Motorboat

and

Reader’s Digest.

The plywood paneling shone with lemon oil. Photographs of autumn scenes in stamped brass frames hung around the room. On a table at the end of the room the television set faced them.

At the end of the sofa a cabinet with glass doors, and inside, Mernelle’s bear collection: glass bears, ceramic, wooden, Bakelite, plastic, papier-mâché, a varnished dough bear from Italy, a straw bear from Poland, stuffed cloth bears, twig and stone bears and a metal music box bear with a crank in his back who played ‘Home on the Range.’ She did not know why she collected them. ‘Oh, it’s something to do, a hobby, like. I don’t know, I just like them.’ Ray brought back bears for her from every place he went, from the lumber conventions in Spokane, Denver, Boise, from other countries, from Sweden, even Puerto Rico and Brazil. In a way he collected them; she arranged them on glass shelves. She had to like them. She did like them.

Ray switched on the television set. The blue rectangle swelled out at them and the crooked figures shimmied through desperate snowfall. The images held their attention like flames in a fireplace. At eight-thirty Mernelle went into the kitchen to make Ovaltine and cut the pie, still as warm as sleeping flesh. She arranged the dessert plates, white with blue rims and gold leaves, on the tray, poured the pink-tinged Ovaltine into the cups that matched the plates. Against the sound of the storm she made a chinking of china, played the silver sound of spoons. In the living room Ray set up the little table, spread the yellow cloth on it. She set the tray down gently. They watched the flickering story, their forks muffled in crust and cream. The sight of his empty knees rent her. If there’d been kids they would be putting them to bed about now. Ray would tell the bedtime story. ‘Once upon a time there was a little girl who lived on a farm at the top

of a tall, tall hill. Her name was Ivy Sunbeam MacWay, better known as Sunny to all and sundry. Even on Sunday.’

Late in the program the phone rang. Ray stretched. His sharp elbows pointed the plaid shirtsleeves.

‘If that’s someone at the mill—’

‘I’ll get it, Ray. You shouldn’t have to go out on a night like this.’ The black streaming night. She answered the phone, but he was up, standing in the doorway and listening. The hollow voices of the television sank into grim music and the tough voice ‘… I’m a cop … on the day beat out of …’

‘Yes, yes.’ In the nervous questioning voice reserved for strange authorities. Someone was telling her an address. She listened, gestured for a pencil and paper. He stood beside her watching her write a number, directions to a town a hundred miles away in the mountains. ‘She is seventy-two years of age, she was heavyset, but thinner now, maybe five-foot-five in height, I’m not sure. She is shorter than me. She wears glasses.’ She listened to the young voice, ‘I tried to call her yesterday afternoon a couple of times but didn’t get any answer. What time? Well, I’m not sure, but the rain had just started. Maybe about three. Tried again this morning. She is out quite a lot so I didn’t think anything of it. Yes. Yes, I can bring a picture took of her last spring. Me and Ray’ll start right away.’ After she hung up the phone she wondered why her hands didn’t shake, she pressed them against her eyes, then dropped her arms limp to her sides, sucked air in past her teeth.

‘That was the New Hampshire state police. Some deer hunters found Ma’s car way up on a logging road. Looks to have been there a day or two they think – there’s snow on it and no tracks around it. No answer at her phone the police said. It just rings and rings. They had Mr. Colerain drive by the trailer and check, Sheriff Colerain, and she’s not there. They tracked us down through Ott.” She was dialing, her fingers knowing the familiar number and stood listening to the burr-burr, burr-burr, imagined the ringing in the empty trailer.

‘They said they don’t know how the car could ever have drove up there. It is hung up on a rock. They said it is all just rocks and

stumps and swamp, that a bulldozer would of had trouble making it up there.’

‘Is she hurt?’

‘They don’t know, Ray. There wasn’t nobody in the car. Her pocketbook is on the seat. There’s money in it. Thirteen dollars. They needed a description so they can call the motels and hospitals. They said it is snowing to beat the band up there. Ray, what in the hell was she doing on a log road up past Riddle Gap, New Hampshire? You know some burglar or worse could of broke in, kidnapped her, stole her car.’

‘Get your warm duds on. This will be a bad trip through them damn New Hampshire mountains.’

The land steepened on the east side of the Connecticut River. Mernelle sat on the edge of the seat, braced her hand against the dash. The road gleamed black in the headlights, the windshield wipers nodded.

‘She’s been funny the last few months, Ray. Remember in August when she came home with somebody’s mailbox dragging off the back bumper? It must have made a terrible noise going down the road and she said she never even heard it. And Ray, the time she tried to cross the brook when the bridge was out and got the car in a hole? She’s been a terror in that damn car. She’s too old to drive, Ray. I’m going to tell her, too, right to her face.’

The rain clicked, grain of ice in each drop. As the temperature fell ice ridges built up at the extremities of each sweep of the wipers, leaving fans of clear glass outlined in ice. The wipers scraped and clawed. Ray pulled over gingerly and picked the ice off the wipers by hand. Black ice coated the windshield as he worked on the wipers. He scraped the windshield clear, but in less than a mile had to pull over again and clear the ice buildup. The defroster roared but only produced a saucer-sized rising moon of clear glass, forcing him to drive with his head craning up over the steering wheel.

The steep roads had not been sanded and the DeSoto slewed, the rear end throwing out on even the gentlest curves. On hills they did and skidded sideways. No headlights came from the other direction

but far behind them Ray saw the slow crawl of another vehicle in the rearview mirror.

‘I bet that’s the sand truck behind us,’ said Ray. They wavered along at twenty miles an hour, the sleet pouring down like salt. In Jarvis it changed to snow.

‘Small favors,’ said Ray. But the tires held on snow, the wipers swept the flakes away. He increased the speed to a steady thirty.

She woke in the hot motel sheets and knew by the sound of his breathing that Ray’s eyes were open. The cramped room, a plastic chair crowding the double bed, the television set, was stifling. Her head ached. The heat was on full blast, and from the gushing air she knew it was bitter outside.

‘How long you been awake?’ she whispered.

‘Haven’t been to sleep yet. I just keep thinking she might be out there. Getting awful cold out.’ He got up and pulled at the Venetian blind, his wedding ring a glint. The slats rose at a crooked angle. A crystalline haze blurred the motel yard light. The fine, fine snow that fell when it was bitter cold. There was the wind, he thought. Even if someone was dressed warm and hunkered down in a hollow tree, in a sheltered corner, how long could they last? Did old farm women burn with fires of endurance or did they let go quick and easy?

‘What do you think, Ray?’

‘I don’t know. I don’t know. It don’t look too good, honey. But we got to keep our fingers crossed. She might be in somebody’s spare room right now. Don’t borrow a worry.’

‘Ray. She’s not in somebody’s spare room.’ He said nothing but folded his long hard arms around her, pulled her up close so her ear pressed against his bare chest. His heartbeat thudded, his chest rose and fell with his warm breathing, a sleepy, vanilla smell came from him.

‘Ah, Ray, don’t know what I’d do …’ But, folded in the sweet circle, she imagined Jewell in the drifts, one arm stretched out rigid before her, the other folded across her breast as if to pull an arrow from her throat. Snow crackled in her hair and drifted into the cold shell of her ear.

‘Ray, poor Ma,’ she sobbed. And he stroked and stroked the fine hair until it rose in the darkness to meet his descending hand.

By midmorning the temperature was fifteen below. The snow drifted in hissing knife edges. A fresh search party had started out at seven with the first slow light. Mernelle talked to Dub in his Florida office. The connection was bad as though ice were forming in the lines.

They sat on plastic chairs in the dispatcher’s office in maddening idleness. They strained to understand the coded, crackling messages. Men came in and went out. The room smoked with cold. Smoke rankened the air. Ray began to think about the pipes under the sink at home, the heat of the house dying away.

‘It’s no good both of us waiting here. They could freeze up. What about if I go back and take care of the pipes and you stay here. I’ll come back as soon as I can. And if they find a trace, you call me and I’ll come right along.’

On the next day, glittering cold, Ray came back but they had not found her, and on the third day the snow began again. The search was finished. Mernelle and Ray sat in their car in the play of heated air staring at the gas station where Jewell’s orange bug, dented along the bottom panel, muffler gone, spattered with congealed mud and oil, stood off to the side. As the new snow filmed the dirty metal Mernelle said she’d never see it run again.

‘This family,’ she said. ‘This family has got a habit of disappearing. Every one of this family is gone except me. And I’m the end of it.’

‘Don’t say that, honey. We might still get lucky.’

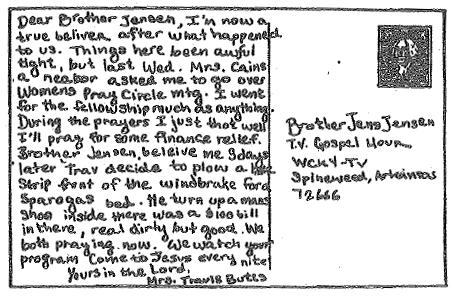

‘The luck was used up long ago, Ray. Bloods been running on empty since Loyal lit out. Damn him, sends his damn postcards every year or so but never lets us know where to write. You realize he don’t even know Pa’s dead? He don’t know about the barn or what happened to Pa, he don’t know Ma moved into the trailer or that you and me been married almost ten years or that Dub is rich in Miami. Don’t know that Ma is lost. Sends his dumb bear postcards. How many of those bears have we got to see? What makes him think I want to hear from him? I don’t care about his damn postcards. What now? Put some kind of notice in every paper in the country, “To Whom It May Concern. Jewell Blood lost in the snow on Riddle

Mountain in New Hampshire, will her oldest son who hasn’t been heard from for twenty years call home”? Is that what I should do? At least I know where to get hold of Dub. At least I can call him up. I got an address. I don’t need to wait for a postcard.’

IV

40

The Gallbladders of Black Bears