Postcards (37 page)

Authors: Annie Proulx

It was all real estate knowledge, prime properties, not the crude hawking of condos and old-age death parlors to the ancients from the north, but scholarly appraisals, landmark status research, a shrewd eye for next year’s extraordinary properties. They knew the importance of discreet arrangements and offerings. They could talk to sheiks, seekers of political asylum, men who had business dealings to the south. Aesthetics. Look what Pala had done with Opal Key Reef. Every major magazine in the country had run photos of the antiqued shell-stone houses and the gardens designed by Burle Marx, fantasies of curious plants.

The first needle of sun came through a hole in the canvas awning and drilled onto Dub’s linen knee. Many of the properties Eden handled never came on the market when the owner wanted to sell; the sales were privately arranged by Eden, Inc. No one came close to Eden. He and Pala had an instinct for the protected properties, islands joined to the mainland by a single causeway or bridge. Peninsulas with a single approach road. They understood the clients who needed certain properties. He wished the tax people would understand him.

He tilted the coffeepot, the black fluid arced into his cup. On the

other side of the pool the garden yawned with caves of shadow, early heat ricocheted off leaves, ferns arched, petals unfurled. Pala might sleep until ten. He never shook the early rising habit. He got up and walked toward the garden, carrying the white cup in his artificial hand with its perfect plastic nails.

Here was Eden. They didn’t go to the Green Swamp now. The garden’s odor, heavy and perfumed as a split fruit, filled his mouth and throat. The moist air pressed against him, the moss cushioned his footsteps. The banyan tree was the center of the garden. He had bought the place for this ancient tree with its humped root knees, its branched arms and rooting thumbs, the twists of vine and florid blossom, the molded, shreddy bark and falling, falling fragments. There was something he loved in the smell of decay.

Up into the pointed hills, gumbo roads slippery as snot when wet, his landscape of crooked rocks. The antelope sentinel’s snoring warning to the herd in the draw, the herd bounding through a strew of flowers close to the earth like rainbow grass. The antelope step over fossil tree trunks, broken stone stumps with the rings still visible, the stone bark encrusted with orange lichens.

The worn sandstone layers hollowed and rippled by ancient water in this waterless land, this lake bottom heaved into yellow cones still booms with the hoofbeats of the horses of Red Horse, Red Cloud and Low Dog, the great and mysterious Crazy Horse, Crow King and Rain in the Face, kicking up fragments of fossil teeth. They come tearing out of ravines, rise up with killing smiles in the astounded faces of Fetterman, Crook, Custer, Benteen, Reno. He hears the slipping twinned voices canted at each other in fifths, the Stamping Dance of the Oglala, the voices whirling away and dropping, together, apart, locked in each other’s trembling throats. The fast war dance, hypnotic and maddening, has irradiated the sandstone. He has only to hold a mass of stone in each hand and bring them together again and again, faster and faster, twice the speed of the beating heart.

Maddening. On the counter of a general store in Streaky Bacon, Montana, a box of discarded patient cards from an asylum in Fargo. He looks through them. Everyone looks through them. The corners are broken and greasy. Photographs: a description of the subject’s mania, revivalism, melancholia, masturbation, dementia. The Indian’s face balanced between his fingers. The smooth combed hair, but the jacket askew and stained. The still face, the black eyes, and the tapering fingers locked around an accountant’s

ledger. Although it seems to be the Indian, laconic script says ‘Walter Hairy Chin.’ Nothing of blue skies nor hundred-dollar bills.

43

The Skeleton with Its Dress Pulled Up

YEAR AFTER YEAR Witkin had worked on the camp, sketching plans for a sleeping porch, a double garage, adding another bathroom. There were more rooms now. He planned a stone fireplace the size of a steel mill hearth. He cut and stacked his own firewood. Built the woodshed. He thought about a sauna and a swimming pool, planned to enlarge the stone patio to a sweep of fieldstone paving. He was shrewd, called around for lumber prices. The pickup truck was new each spring, fitted with a varnished oak rack, the word

Woodcroft

in old English letters on the doors.

His hands and arms developed a strength they’d never had when

he was young. Muscles under his old skin. Yellow callouses thickened his palms, his fingers were rough. He could have been a carpenter or worked in construction.

He told Larry it was in the back of his mind to make the camp into a retirement place, maybe a place for two if he remarried.

‘You get married again? You weren’t the type to get married in the first place. You’re married to work, Frank. If you knew how to relax, maybe I’d take you seriously. Who you got in mind, Mintora?’ Larry brought women up sometimes, Frieda, a sculptress with thick hair the color of bison wool; Dawn, the documentary filmmaker getting ready for a trip to Antarctica; and Mintora, a breasty woman Witkin’s age whose work was woodcuts, her subject, gorillas in hot-air balloons. Yes, it might have been Mintora of whom he was thinking, the unshaven slender legs, the jutting hair under her arms, the comments on his woodworking.

‘Wouldn’t you like to have some rice pudding?’ she said once and opened a hamper packed with pots from a city deli. She brought him a brass doorknob with a beaded rim, a copper advertising plate showing, in reverse, a woman washing a corset in a sink.

The roof of the abandoned farmhouse below had fallen in. No one could guess there had been a farm there. The trailer park spread wide, dusty lanes jerked along the hillside. When the wind was from the south Witkin could hear engines and shouting. Yet on his high hundred acres the wild woods came ever closer, the trees multiplied.

Larry, grown heavy and slow, said it was harder to get around in the woods. He puffed and coughed, walked up grades in long gradual ascents that added miles to the day. They walked out with the guns but rarely fired at anything.

‘Frank, I can’t do this any more. I never thought I’d hear myself say that, but I can’t do these climbs. Too much easy living. You don’t get exercise selling pictures.’ They were no longer close. Yet both pretended.

Alone at the camp the oak trees scintillated at Witkin, the shrubs and young trees in color seemed to leap off the tawny ground. The sky vibrated, the taut drumhead struck. He shuffled through grass the color of bread crust, leaves of burnt sugar, charred letters, the sifting

of needles, his head scratched by roots dangling in air where the soil bank had slid down, his boots slipping on the log over the water, following the miles of stone wall drifting away into the woods. He needed Larry still to guide the way. He could not sort out the trees, could not understand the wind direction or the scramble of branches. The confusion of trees pressed in on the camp. Raspberry thorn twisted under the step.

He began to put the chaos of nature in order. The sinuous woods music, once so beguiling, had taken on a discordance like a malfunctioning speaker, the same endless hum as the high-tension wires when he had stood beneath them waiting for Larry to drive the deer across, confusing him so that he had not heard the deer come, had only seen tawny motion. He had never wanted to hunt; that was only to please Larry, the unknown brother.

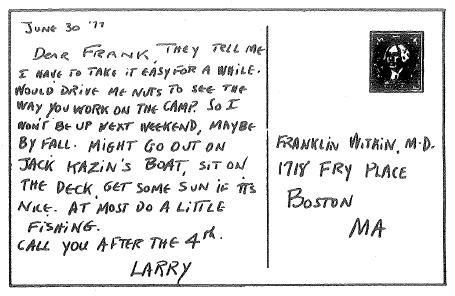

On Jack Kazin’s boat Frieda was surprised when Larry arched his fat back in the canvas deck chair, threw his head back as if readying himself to sing an aria, then hurled over the chair arm. Full coronary block.

The week after Larry’s funeral Witkin hired Alvin Vinyl and his cousin to cut and drag away the shrieking maples around the camp. Time rushed at him. He urged them on with promises of money. They cleared a great open square. Leaves shriveled in the glare, the secret moss withered. A stump puller tore roots from their two-hundred-year grip of the soil in fuming black fountains. The grader tamed the rumpled soil and Witkin sowed grass seed for his lawn in the wilderness. Other projects swarmed in his mind; he had to hurry.

The equipment for the new lawn – riding mower, aerator and de-thatcher, rollers and scythes – were jumbled into the garage. He planned a toolshed, then the fireplace chimney, and the addition, two rooms and a studio. Kevin, his son, said he’d come for the summer. In his second year at university, he had no summer job. Witkin offered a season’s pay for a season’s work, knowing as he spoke the stiff sentences about getting to know each other better that neither of them would be suited. Kevin’s mallowy hands seemed useless for anything beyond scratching and fluffing.

The first day Kevin worked with his shirt off, pretending not to hear Witkin’s warnings of sunburn and cancer. He slept through the fine morning of the second day, crawling out of his sleeping bag only when the din of the chugging generator, power saw and hammer reached a devil’s pitch. Slouched and spoke in monosyllables. Witkin hated him again. He did not recognize Kevin as his mortal flesh. And the other one, the twin sister, what of that timid, humorless girl in her pink blouse who unerringly made the wrong decisions, who was now in Zambia with the Peace Corps? The instinctive, binding love that loops through generations failed.

They roofed the toolhouse roof with sheets of galvanized metal. The scalding height shimmered. Kevin drank gallons of beer, hammered irregularly, pissed from high off the roof instead of corning down the ladder. Heat dared against their arms and chests. Sweat streamed. Kevin, sensing Witkin’s need for martyrdom, quit on the fourth day.

‘I can’t hack this. I’m taking off. I’d rather shovel coal in hell than do this. What the hell are you building this big place for?’ It was what they both had expected. There was no fire in their argument. Only the chewy satisfaction of mutual dislike.

After Kevin was gone the elderly stonemason, the color of stone himself, came to build the chimney. Witkin hired and hired. There was not enough time to do it done. A crew of carpenters hammering the skeleton of the addition, filling it with wood and glass, the trucks straining slowly up the hill with loads of gravel and sand, with turf and boards, flashing, nails, insulation, hinges and latches, wire, lights, drywall, tape and spackle, paint. Hurry.

When they were done Witkin started the stone patio himself. The cast iron benches had already come, shipped from South Carolina in pine crates that smelled of resin and enamel. He would use the garden tractor to move the stones from the old wall at the edge of the forest to the sand bed.

He started on the wall very early in the day. The sky poured blue light, the backhoe popped. Stones, molded with fine maps in lichen and moss came away growling and grinding, throwing off limbs and rotten branches. The backhoe teeth gouged the delicate verdigris

patina. Ruffled edges of continents and islands tore away, the lapping moss seas bunched, showed the film of soil below. The smell of leaf mold made him sneeze. Was there no relief from that dark wildwoods stench?

The small flat stones in a pile. He would work those into the interstices once the big rocks were in place. The round and irregular shapes went into the rubble pit.

He uncovered a big stone, the black edge four inches thick, the corners neatly squared. He looped the chain around it, drew it to the patio. In its wake a crushed trail. He turned it over to see the other side. A flower of white mold spread across the dark slate, its spidery rays like a burst galaxy. Crushed spider cocoons. He turned it again so the good side was uppermost and, with the crowbar, jimmied the stone in place.

He worked the morning scratching at the sand where one side sloped more deeply than the other, prodding and settling the stone into the best lie. If he had a dozen stones like that, he thought. He hoped for at least one more, and went again to the wall.

The stone had bridged a cavity filled with leaves and a spill of seed husks from an old mouse nest. He stooped, swept at the curled leaves with his hand. And, in startled recognition, pulled back his hand from the white curve of skull.

Larry, he thought for a moment, somehow Larry had gotten out of the Bronx cemetery and under the wall.

But it was not Larry.

Carefully he took out the leaves in small handfuls until the crooked bones lay under his stare. The flawless teeth smiled up at him, but the small bones of the hands and feet were missing. The right arm was gone. The remaining arm and leg bones, marked and grooved by the chiseled gnawings of mice, were brown with leaf stain. A shoe sole, curled and twisted away from its heel, lay in the pelvis like an embryonic husk. Behind him he heard the idling garden tractor chuff.

A pioneer grave. Some early sender’s wife, exhausted by childbearing, or, perhaps, scalped and slain by Indians, or killed by typhoid or pneumonia or milk fever. He had blundered into the cool privacy of her grave.

‘Poor woman, I wonder who you were?’ he said. In respect he undid the clay’s work, dragged the stone back to the wall and levered it home again. He would not desecrate a grave.