Postcards (17 page)

Authors: Annie Proulx

In Grand Junction he follows a black railing down into a basement with the smell of sweaty men and rolled maps. Pickups park along the khaki street. Most have trailers with gas cylinders chained on behind. And everywhere are men in dusty, crumpled clothes putting nickels in the red Coca-Cola machines. Hard hats to the wind, cupped hands, the match flame and the loose ribbon of smoke. He sees a hundred government men with name tags, AEC vehicles, exploration division equipment. The sprawl of black rock in a store window.

CAMPING SUPPLIES & URANIUM – LISTINGS – SALES

.

Prospectors in from the white bluffs look over the latest anomaly maps, talk of trying their luck somewhere else. The towns shake with the passage of dusty, dented jeeps, the exhaust systems torn out, bulldozers and backhoes roll through on the semibeds. Stake trucks loaded with burlap sacks of ore. Along the roads and in the countryside the discarded cores lie in heaps on the ground. Cigarette butts, wire, dust, dust. No goddamn women. The dusty airstrips, the little white planes flown by Air Force vets in rolled-up

sleeves, happy to be flying again. Aerial maps. Rapid City, Cheyenne, Laramie, Burdock, Dewey, Pringle, Wind River, Grants, Slickrock, Green River, Chuska District, Austin, Black Hills, Big Horns, Big Indian Wash, Big Beaver.

Big bust, maybe.

BEEMAN ZICK HAD the lower bunk and the upper hand. He came out on top every time, but he’d been unlucky in his cellmate, a damn, dull old farmer who didn’t do much but sit on his bunk, cracking his knuckles and staring at the door. Old bastard wouldn’t talk about nothing. Who wanted that leathery old horse. Not Beeman Zick, who yearned for the taste of dill, pickerel fishing and love.

The son, oh, he was different. He wished they’d put him in with the son. Guy only had one arm (advantage) and was getting bald (too bad, but who can tell in the dark), but what a ass, as plump and sweet as Christmas cake. And there the son was, in with the Frenchy, and the Frenchy, despite his years in the lumber camps where all they did

was chop down trees and stick it into each other, was an on-the-knees Catholic who’d almost rubbed his lips off kissing first the gold cross around his neck and second the photographs of his fat wife and daughters. Wives. Somebody noticed once he had two sets of pictures, and they didn’t match. Then it came out. One set down in New Hampshire, in Littleton. One set up in Quebec, in Roberval. Total thirteen daughters and not a single fucking boy. And stole a peavey from one of the little operators up in the kingdom, went on a rampage after drinking half a pail of potato wine and used the peavey to pry the back wall off the house of absent timber baron Jean-Jean Poutre. They found Frenchy lying naked in the silk sheets, surrounded by silver-framed photographs, pepper mills, embroidered scarves, mahogany-backed military brushes, beeswax candles, engraved letter openers, empty champagne bottles, leather-bound books, bell pull tassels, crystal vases, stuffed birds, a pearl-handled nail file, walking sticks, perfume flagons, powder puffs, patent leather shoes, quires of creamy paper, imported fountain pens, sheet music, and a telephone directory for Oyster Bay, Long Island. ‘Call me up sometime,’ was all he’d say.

Couldn’t tell any of this to the old farmer. Oh, you could say it and plenty more, but that’s where it stopped. He didn’t hear a thing except the devil shouting in his private ear if those rapid whispers were proof. Beeman Zick couldn’t make out a word. They made the farmer take his exercise alone, alone except for the guard. They said the son wanted to kill him or he wanted to kill the son. Keep them apart. That’s what they said and that’s what he thought, and he was as surprised as anyone else when the old farmer hung himself.

Beeman Zick was wakened out of the sweetest last hour of sleep. He drowsed in the warm pillow, unwilling to come fully awake, and tried to identify the noise through a dream haze. It was like someone snoring or talking in his deep, a choked voice sound, and a fleshy slapping like the unstoppable moment, then the pattering of liquid accompanied by thrashing whumps and the hollow clangor of the water pipes. Beeman Zick had heard the water pipe song before. He leaped out of bed and stared at the old farmer writhing in the noose of his shirt arm, shirt tied to the water pipes, bare feet scrabbling against the wall, legs wet with urine.

‘Guard!’ bellowed Beeman Zick. ‘We got a dancer here.’ But by the time they cut the old guy down the dance was over.

Leatherette briefcase bouncing against his leg, his upper body encased in a tight plaid jacket, head rocking left, right, left, Ronnie Nipple came up the May path. In the drive his dusty blue Fleetline Aerosedan cooled. The spring peepers bleated down in the swamp, and even in the closed kitchen the relentless trilling pummeled everything that was said.

‘Jewell. Mernelle. This is a sad time but life goes on,’ his voice pitched in terrible softness. The stain on his chin glowed.

‘Don’t talk like a funeral director, Ronnie. I had enough of that. Life don’t go on, not like it used to. What we need is some help in straightenin’ out this mess. The insurance company and the bank fellows come up here every day. He left us in a terrible pickle. No money, nowhere to go, the boys gone. It used to be your boys would go into farmin’ somewheres nearby. The young ones start out in farmin’ the older men would give ’em a hand. But now. If you can’t help us find a way out I don’t know what I am goin’ to do.’ She snuffled and wept a little against the urgent swamp trill. Her fingers laced through each other. The wedding ring was worn to the thinness of a wire. ‘Ah, I dunno. When I was a girl there were so many aunts and uncles, cousins, in-laws, second cousins. All of ’em livin’ right around here. They’d be here now, that kind of big fam’ly if it was them times. The men would put the plank tables together. Every woman would bring something, I don’t care, biscuits, fried chicken, pies, potato salad, berry pies, they’d bring these things if it was a get-together or a church picnic or times of trouble. The kids go runnin’ around, laughin’, I can remember the mothers tryin’ to hush them up at my brother Marvin’s funeral, but they’d just slow down for a little bit and then start up again. And here we sit, the three of us. And that’s all.’

Mernelle sat dreamily rocking, staring out the window at the scorched barn foundation. She was apart from this talk. Fireweed had already surged up out of the cavity. The trilling was maddening. The weeds spurted, mallow, peppergrass, dog strangle vine, stinking wall

rocket. The barberry bush near the old dog’s grave in sullen flower, the moths nipping and jittering.

‘Jewell, you was always a good friend to my mother when she needed it. And you know what I’m talkin’ about. I don’t know the whole story of

that,

when Dad passed over, but she let on quite a bit. And I’m going to be a friend to you and Mernelle.’ His voice limped away. Sitting at the table, his papers spread across the worn oilcloth like boats adrift on the seas, the brown kitchen light sifting over his hands.

‘I never dreamed in all those hours her and me sat talkin’ at this table that we’d be in the same fix one day. Your mother was a decent woman and a good soul. Somebody got sick why she’d go right on over and help out. Fix supper, do the warsh. I’ve often thought in the last few weeks that if she was here she’d know what I am going through,’ thinking both Toot and Mink had killed themselves in shame. Although the shames were different. She felt again that new stir of curiosity about her own death that came to her in the early morning, a half-eager willingness to consider its possible form, a stir that came and went like a jumping muscle.

‘Well, I been workin’ on this thing of yours, and I guess we’ve got a way to pull you out of the mire. Of course, keepin’ out is goin’ to be the problem.’

‘Ronnie. I want you to know you’re a decent neighbor.’

Mernelle made a face at the window, batting her eyes, stretching her mouth in mock humility so her upper teeth hung over her lower Up. The peepers shrilled. Blue-eyed grass winking, the crushing scent of lilac.

‘It’s complicated and it won’t be too easy for you. It means splitting the farm into three parcels. I got two buyers and I managed to save the house and a couple acres for you to live in, have room for a garden.’ He drew on the back of an envelope. The farm became a shape like a pair of trousers, each leg a division of the property. His ballpoint pen stabbed the lines of demarcation. ‘A piece of the orchard so you can keep up your pies and applesauce. Ott has offered a real good price for the cropland and pasture, that field of Loyal’s, prob’ly more than it’s worth right now. And I got a doctor from Boston wants

to buy the woodlot and the sugarbush, build a hunting camp up in the woods. Between Ott and the doctor you’ll be free and clear of the debts. I’ll lay it right out for you, Jewell. You’ll have to swallow the sight of other people on your place and you won’t have much left over. A roof over your head. Garden space. Maybe eight hundred dollars cash. Somebody’s gonna have to scout around for a job, maybe both of you, what with Dub where he is. But that’s how it goes. I don’t need to tell you Jewell, when trouble comes we just have to do the best we can.’

‘It’s awful good of Ott to step forward, at least keep some of the farm in the family,’ said Jewell, mouth filling with the bitter words. Her voice shuddered, fell away. ‘This farm been in the Blood family since the Revolutionary War days. I’ll never know why Mink didn’t go to Ott, why he didn’t think the farm could bring anything,’ she half-whispered, thinking that Ott could have helped Mink, should have seen the trouble and stepped in. Brothers turning their backs on brothers.

‘Well, Jewell, you got to know the market. Mink didn’t even know there was a market, a real estate market. You folks kept to yourselfs up here. Missed out on a few things. Changes. It’s not just what a farm’ll bring for a farm, now. There’s people with good money want to have a summer place. The view. That’s important. See the hills, some water. The places with the barn right across the road from the house don’t move good, but if there’s a pretty view, why …’ The word ‘pretty’ sounded awkward in his mouth.

He meant that he, Ronnie, had smoothed out, had learned something. Jewell thought of him years earlier, a dirty boy who loped in the woods with Loyal, a tagalong with no ambition that she could see. Look at him now, see his jacket and briefcase, shoes with crepe soles. She thought of Loyal, lost out in the world, of Dub, locked up.

He must have been thinking the same thing. His fingers limped among the papers, folded the corners.

‘You get in touch with Loyal?’

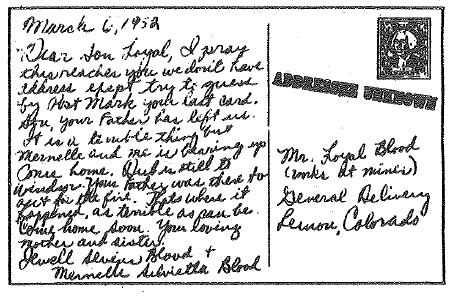

‘He wrote he was workin’ in a mine about a year ago. I tried to write to him about Mink, but he don’t think to send his address, or I guess he keeps on moving.’ Loyal always said that the reason he

liked to hunt with Ronnie was because he could tell what you were thinking, that you never had to stop and talk or wave your hands in dumb signals. He knew.

‘The Boston doctor, now. Is he a half-decent feller?’

‘Doctor Franklin Saul Witkin. Seems nice enough. About forty, forty-five. Real neat. Quiet-spoken. Wears glasses. A little stout, high-colored. Skin doctor, specializes in skin ailments.’

‘Can’t be much to that, wouldn’t think it would make anybody a living, would you.’

‘Makes enough so Dr. Witkin can drive a big Buick and wear a gold wristwatch. And buy a hundred acres of your farm. Course he’s got to have a right-of-way to the top of the hill.’

‘What kind of name is Witkin?’

‘I believe it’s a German name or Jewish name.’

‘I see,’ said Jewell. And she breathed in slowly. He could have said Chinese.

The kitchen had not changed, Ronnie thought. Mink’s grimy barn cap still hung from a hook near the ell door. The linoleum, the ivy crawling over the walls were as they always had been. There was half a loaf of bread standing on a scarred board, the knife with the broken point beside it; the sink was full of chipped dishes. He’d pulled out all the old kitchen fixtures at his own place when he married, covered the pine boards with Armstrong floor tile, a clean floor for little Buddy to crawl on, a chrome and Formica dinette set, a combination oil and gas range. He’d converted the old summer kitchen to his real estate office. A desk, three chairs, telephone, a big mural photograph of autumn mountains on the wall that had cost plenty. He thought there was no telling what Loyal would do when he came back and found the farm sold. He wouldn’t blame himself or Mink or Dub, not Jewell nor Mernelle; he’d blame Ronnie Nipple. Cross that bridge when he came to it.

Ronnie was back two days later, coming out of the tender rain with the papers for her signature, the deeds, the stiff contracts and lien release documents. An earthworm writhed on the edge of his shoe, embedded in the rippled sole. But his ballpoint wouldn’t work no matter how hard they scribbled with it on the back of an envelope. Jewell had

to get Mink’s old nib fountain pen with the mottled green barrel and the nearly empty bottle of ink and scratch her name. The farm was gone. Only the house on its two-acre island held a line.