Postcards (16 page)

Authors: Annie Proulx

Mink felt himself slow as a nailed board. The milk pulsed, empty seconds hung between the spurts. The cows shifted and bawled. It was worse, whatever it was, this morning, the way they fidgeted. There was a crack of memory of something from a long time ago, he and Ott climbing on a board fence with a ferret-faced boy, Gordon or

Ormond, his father and some other neighbors leaning over the fence. A lot of men, a low twist of voices. There was a pig on a bed of straw. There was a .22. Or was it a .30-.30. The matter was serious, but there was a feeling of coming through whatever it was all right, that it was a bad, but fated, part of life. But he couldn’t remember what it had been about. The night before he lay awake late into the night trying to remember what was wrong with that pig, and was deathly tired this morning. The automaton-like pulling on of clothes, the groaning of the winter stairs, the rattling of lime deposits in the kettle all seemed too heavy to endure. The kitchen seemed a rabbit cage, himself the rabbit subdued into crouching silence.

Now Dub’s barn clatter, the scrape of the pail handle on his homemade wooden arm with the old gambrel hook screwed into the end, deliberately crude and heavy, the light stainless steel hook they’d paid so much for thrown into the river after the last fight with Myrt. He’d heard the wildness in Dub’s voice, like the town idiot years ago, Brucie, Brucie Beezey, greyhaired and screeching for roasted apples like a baby for the tit. He could hear that note in Dub’s voice now and then. What did he want, somebody to say it was all going to be o.k.? He should know better by now, crippled, divorced, a father who’d never seen his son. He was always a fool. A goddamn periodical with the boozing.

He leaned his head against the cow, stripping, stripping. What he thought was that in some way he didn’t understand yet, this cow was going to finish him off. And tired because he’d been awake most of the night trying to think of the trouble with that pig and come up with a way to break from his downward course. Poorer every year, the work harder, the prices higher, the chances of pulling out of it fewer and fewer. It was so different now. He couldn’t get his bearings. There had been poor people when he was a kid. Hell, everybody had been poor. But things kept going, like a waterwheel turning under the weight of flowing water. Relatives and neighbors came without asking to fill in. Where the hell were they now when he was sinking under the black water? Ott moved, Ronnie out of farming, Clyde Darter sold out and disappeared into Maine. The bank had changed hands, bought out by some big outfit over in Burlington, mean sons.

The Dovers were storing hay in the old Batchelder house, the bales tilling the kitchen and front room, packed on the staircase, pushing the banister spindles out. He remembered Jim Batchelder as if he’d seen him last night, the chapped face and parsnip nose, could hear him talk to his horses in his spare voice. And the past swelled out at him with its smell of horses, oats and hot linseed poultices. When the horses went the people went.

But how to get out of this? Dub and his screechy voice a weight, Mernelle with the constant harping about going to the movies and a goddamn ‘Victoria’ hair wave and Jewell, not saying much but showing what she thought by staring away when he was trying to tell her something, twitching her head as if a fly was at her.

And this. He couldn’t believe that he was wearing out. His arms, his knotted thighs, the swelling shoulders looked the same, but every joint flamed. The artheritis. It had bent his mother like a hoop. She’d twisted in her chair for years, calling for hot water bottles, scalding hot, as hot as they could get them to relieve the inner twisting that bent and bent her spine like fingers at a length of basket osier. And with the image of his mother arched in a hoop of pain, at last came the memory of the pig on the straw, tearing convulsively at its side until the loops of gut fell out and dragged through the muck, the pig stepping on its own bowels before sinking to the straw and soil it rolled its mad eyes and strove to bite through its flanks. And this cow, swaying and lifting her back leg to scrape and kick at her raw side – Mink stopped milking, got up and studied the staring eye, noted the stringy slobber.

There were only one or two tricks left in the bag now. The cunning tricks.

‘You know what we got to do,’ he said to Dub.

‘We got to finish the goddamn milking, I got to feed these goddamn cows,’ said Dub, his voice muffled in the milk room.

‘No. I mean about the farm.’

The water pail slopped as Dub raised it from the sink.

‘Sell it, you mean? Be the smartest thing you could do. I been at you to sell it for God knows how long. Do what Ott did, get a place with electric. They’re never gonna bring it in here.’

‘Not sell it. Don’t you know nothing? Don’t you know the kind of a mortgage we got on this thing even if we was to sell it even for the top prices they’re getting for this size of a farm even if it had the electricity and all, we wouldn’t clear enough over the mortgage payoff to buy a pair of earmuffs. And there isn’t no electricity. Even if this farm was perfect it’d be no good. That’s the God’s honest truth and now you know. We can’t make nothing on selling it. We can’t break even. That is not the way out. Don’t you think I thought of that the day after that son of a bitch left? We wouldn’t get nothing. How do you think your mother and me is supposed to live? We got fucking nothing.’

‘The cows.’

‘The cows. The cows. That is why we got to do something else. And damn fast. Come over here and let me show you something. You’ll see why the cows isn’t no pot of gold. You’ll maybe get it in your thick head that we are at the place now where we got to dodge.’

He pointed at the cow, her head stretching out, the craning neck, the tongue rasping at the raw side. Her eye showed a ring of white. Mink gestured at the row of stanchioned beasts. Dub stood, back against the door, staring. The cow bellowed and strained to pull her head through the stanchion.

‘What the hell is wrong with them?’

‘I believe it’s Mad Itch. They got the Mad Itch.’

‘You want me to go for the vet?’

‘You are the stupidest son of a bitch I ever seen. No, I don’t want you to go for no vet. I want you to go for the rifle and five gallon of kerosene.’

17

The Weeping Water Farm Insurance Office

THE OFFICES OF the Weeping Water Farm Insurance Company took up three rooms above the Enigma Hardware. The wooden floorboards creaked with distinctive sounds. Steam radiators under the windows put out tremendous heat that made the employees drowsy and secure on stormy days.

In the first room Mrs. Edna Carter Cutter, secretary, receptionist, information bureau, guard dog, indoor gardener, coffee maker and caterer, bookkeeper, weather forecaster, supply clerk, bank messenger,

mail distributor and comptroller, sat in a leatherette chair amid two hundred potted houseplants. They crowded every surface, velvet plants, wandering jew, a purple-leaved Ti plant from the South Pacific, African violets by the dozen, a great leaning Norfolk pine in a lard tub, a lipstick plant swinging over a file cabinet, a kangaroo vine over another, a fatsia in a jug behind the door, a thicket of dumb cane beside the umbrella stand, a Boston fern, the giant of the collection, stretching its fronds over the Gestetner copier. Most of the plants had come as condolence gifts on the death of her son Vernon, run down in New York City by a drunken Marine in a stolen taxicab.

The office of Mr. Plute, the manager, was in the back with a view of an old cattle pound. There was an oak desk and three chairs, two oak file cabinets and an oak coat rack with brass hooks. The upper half of the door was set with a sheet of frosted glass that showed only Plute’s elongated shadow when he walked in front of the window. It was he who had given Mrs. Cutter the Boston fern.

The other room was divided by low cellotex panels into three cubicles where the field men and investigators sat when they were in the office. Each cubicle contained a desk, a chair, a file cabinet, a telephone. When the occupants stood up they could look into each other’s eyes, but when they sat down they disappeared except for curling tendrils of cigarette smoke or the flash of tossed paper clips.

Perce Paypumps was the old man of the office, predating Mr. Plute. He had worn out three oak chairs since 1925 through his habit of tipping back on the hind legs, and had lived through the great flood of ’27, the epidemic of farm fires in the thirties, had tramped miles through blowdowns after the hurricane of ’38 investigating claims of ruin and wreckage. When Plute was away, Perce was in charge. As senior man he had the deep judgment to do claims settlement.

John Magool was easygoing and fat, an ex-paratrooper who had ballooned up within weeks after he got out of uniform, a good talker, a good listener and a good salesman. He was on the road three weeks out of four. When he came in to write up his policies he usually found houseplants on his desk and along his share of the partitioned windowsill. He carried them out to Mrs. Cutter’s office and stood silently, vines trailing over his arms.

‘Oh, those plants! Hope you don’t mind. I was just letting them get a little sun in there and forgot you’d be in this week. You have nice sunlight in the morning, John.’

The third desk belonged to investigator Vic Bake, twenty-two, eager and smart at his first job. He had a face like a scoop of mashed potato, a slack body, a genius for making connections. A congenital wry neck forced him to carry his face thrust forward and tilted a little. Still untouched by life, except for this deformity, he divided all acts of men into connivance or philanthropy. Uncorruptible, a tattletale in youth, a teacher’s pet, a winner of gold stars, he was now trying for a bigger role. Plute, who scented his ambition, thought him a little brute and gave him the ‘fires of suspicious origin’ to weasel into, sent him off to stoop and stalk the state fire inspector, to devil the state’s attorney with his suspicions and his evidence.

A hundred miles upstate, back home, Vic’s teeming family jammed into a house that smelled of dirty laundry. The father left before full light to drive a mad route. Five of the brothers went to their work in the bobbin factory. In Weeping Water Vic had his own room and a bath at a small boarding house near the river. He thought it luxurious.

He walked to the office through the ground fog in the mild February morning. Rotten ice crunched beneath his feet. A rind of snow stretched away into the fog. On the path he saw a blue thread, a stamp, two pulpy cigarette butts, a nail in its ice coffin.

He lined up his black rubbers so the toes touched the office wall, hung his poplin raincoat on the coat rack. He rummaged then, not in Mr. Plute’s office which was locked with two keys, but in Mrs. Cutter’s desk, taking the file cabinet keys and two of her Smith Brothers’ cough drops to suck on while he read the letters and studied the office accounts ledger, then into Perce’s cubicle to go through the folder of outstanding claims and put red mental asterisks in the corners of two cases. The Hakey business where old man Hakey told his daughter’s boyfriend to take a powder and then, lo and behold, at midnight Hakey’s Farm Feeds & Seeds burst into flame. The volunteer fire department couldn’t get the fire truck started. That one stank of arson. And what about this. Cattle auctioneer, Ruben Quilliam. House burned. Nothing really obvious, but Quilliam’s wife had just

divorced him, and maybe he’d been drunk and set the house on fire to show her. He’d look around, talk to Quilliam’s neighbors. Perce was too soft; he had these claims ticketed for payment.

Vic pulled out the

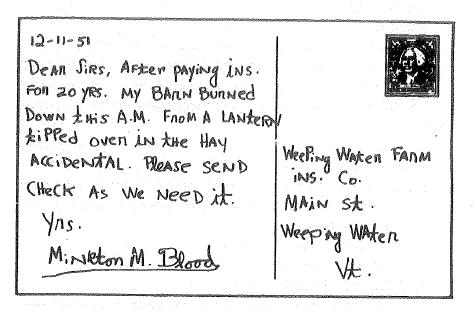

PAID CLAIMS

folder for January, just to take another look. Sometimes you got a feeling for something wrong after the fact. They looked all right. But he didn’t remember seeing this one, ‘Lantern accidentally fell in hay. No telephone. Nearest neighbor a mile away. Driveway closed by snow.’ Perce must have checked it out and not bothered to show it to him. Those lousy old farms with no electricity or phone, something happened and it was all over. Seemed funny they didn’t manage to get even one cow out of the barn. He looked at the fire inspector’s scrawled sketch of the barn. It showed the place where the fire started outside the milk room. About twenty feet from the door. About six feet from the water pump. Seemed like they could have gotten some of the cows out. Or thrown a bucket of water on the fire. And they hadn’t wasted any time putting in their claim. The postcard from the farmer was dated the afternoon of the fire. A fairly big claim, $2000. He wrote the name in his notebook. Minkton Blood. Maybe worthwhile to take a run out there and take a look around. It was never too late.

The wide street open at both ends of town, dust blowing, telephone poles nailed against the blue. ‘Welcome to

MOAB

Utah the Uranium Capital of the World.’ He looks in store windows, cranes at the neon sign ‘URANIUM

SALES TRADE LEASE.’

In Buck’s Sundries there are copies of

Uranium Digest, Uranium Prospector, Uranium Mining Directory Digest.

A poster taped to the glass door promises ‘Miss Atomic Energy Contest, First Prize 10 Tons of Uranium Ore.’ He guesses a value of about $280. If she’s lucky. Another sign, “Thatcher Saw, Realtor, Uranium Broker,’ and a smaller sign beside it, ‘Ranches for Sale.’