Postcards (14 page)

Authors: Annie Proulx

‘Cucumber. You o.k.? Blood?’

‘Dropped my porkchop,’ said Cucumber. ‘Porkchop down in water.’

Loyal understood then that the cold numbness was an inch of icy water, that he was lying in it.

‘Jesus Christ, where’s the damn water coming from?’ His voice sounded panicky. He got up, stood shuddering. Nothing was broken. The water was up to his ankles and his back was sopping wet. His knees stung.

The water came from everywhere. It limped and trickled from the ceiling and walls in thousands of tiny drops like sweat, fed in streams; it welled up underfoot.

‘Jesus, Jesus, Jesus,’ moaned Cucumber. ‘Ah, Jesus, drown in dark. Water.’

‘We don’t know how bad it is. They could be o.k. up there, be tryin’ to get us out right now.’ Berg’s voice was tense but controlled. They stifled their ragged breaths, listened for the chinking sound of hammers. The rock creaked. The heavy drops fell and fell, echoing in the flooding stope. Loyal felt a calm. Was it to be by drowning or crushing? Under the rock.

Berg had been in cave-ins before. He knew the drill. ‘We save our batteries. Don’t turn on your lamp. They’d last us a few days.’

‘Days!’ choked Cucumber.

‘Ah, you old son of a bitch, you can live for weeks in a cave-in as long as you got water. And have we got water. Let’s move up to the high end of the stope. Get out of the slop good as we can.’

They waded up the floor of the stope in the dark until they reached a band of dry rock at the end where they’d drilled in the morning. By groping with their hands they felt the beach of dry floor was about three feet wide, barely enough to sit down on. Loyal fished string

out of his pocket and knotted off the measurement. Berg felt for the tools. The water rose gradually. All around them the patter of falling water, the deadly uniting and tonking. The water crept up the dry strip.

‘This stope is thirty foot high. It take one hell of a lot of water to fill this up,’ said Berg.

‘Yeah, what you do, climb up walls like fly and stay up? What you do, swim around? Have water race? I tell you what you do, is Dead Man’s Float. Nobody never open this up. Standing in grave, Berg. I told you, take third man, bad luck. Now you see!’ Cucumber’s voice was raw. He spit and gobbered in the dark as though Berg had tricked him into this deadly hole.

They stood with their backs to the wall, facing the water. Loyal tried not to lean against the wall. The rock sucked the warmth out of the body. When his legs knotted, he squatted down. By stretching out his hand he could feel the edge of water. The hours went along. Cucumber sucked and chewed at something. He must have found the porkchop.

‘Better save your food. We don’t know how long we’ll be down here,’ said Berg. Sullen silence from Cucumber.

Loyal woke up in a swooning fright, legs numb with pins and needles, knees billets of wood with wedges driven deep. Cucumber was bellowing what, a song, in another language. Loyal put out his hand to steady himself and there was an inch of water. It was up to the wall.

‘Berg. I’m going to put on my light. See if there’s a dry place.’ He knew there was no dry place. The headlamp’s wavering light reflected from the sea that stretched before them to where the rockfall choked the passage. Before he shut the light off again he turned it on Cucumber who leaned his forearms against the wall and pressed his head against his wet hands. The water seeped into his boots. The leather was black with wet, shone like patent leather.

‘Save the fucking light,’ Berg shouted at him. ‘You’ll kill for a light in a couple of days. Sense of wasting it now?’

There was no way to tell how long it had been since the cave-in without switching on the light. The only one with a watch was Berg. The water came over the tops of their shoes. Loyal felt his feet swelling

in the slimy leather, packing the boots tight with stinging flesh. Their calves knotted, the muscles twitched against the cold. There was a raiding sound and he thought it was rock flakes before he reasoned that rock flakes would slip into the water as silently as knives. A little later he knew what the rattling was; Berg’s and Cucumber’s teeth, and he knew because the chills were racking him too, until his whole body shuddered.

‘It’s the cold of the water drawing the heat out of our bodies. The cold will kill you before you drown,’ Berg said. ‘If we can find the tools, a hammer and a chisel, we got a chance to cut out some stone and stand on it, nick out some steps or something, get up out of the water.’ They groped under the water along the wall where they had been working. The useless drills were there. Then Loyal’s lunch box, full of mushy waxed paper and bread pulp, but the slices of ham were still good and he ate one, put the other in his jacket pocket. The stone hammers, chisels and bits were in a wooden carpenter’s box with an ash dowel for a handle. They all knew it intimately, but it could not be found, even when they waded out to their knees, kicking cautiously along the bottom.

‘Even if I walked into it I couldn’t feel it,’ said Loyal. ‘My feet hurt so Christy much I can’t tell if I’m walking or standing still.’

‘Carry it in,’ said Cucumber. ‘Feel it on arm. Don’t know where put it down. Back by the rail line, maybe. Remember almost trip on it.’

Loyal felt the weight of settling rock above them, half a mile.

Cucumber mumbled. ‘Could be there. Maybe I think we don’t need today.’

In the darkness their eyes strained, unseeing, in the direction of the rail line and the tool box, buried now under the rock. The red motes and flashes that trace through total darkness skidded before them. The water rose slowly.

After a long rime, surely eight or ten hours, he thought. Loyal noticed that the pain in his feet and legs had eased to a cold numbness that crept up toward his groin. He leaned, half-fainting, against the wall because he could hardly stand. Berg was retching in the darkness, and between spasms shook so violently his voice jerked out of him

‘eh-eh-eh-eh-eh.’

Cucumber, on the other side of Berg, in the wet

blackness, breathed hard and slow. A steady drip fell near him.

‘Berg. Switch on your light and tell us the time. It’ll help to keep some track of the hours.’

Berg fumbled with his crazy hands and got the switch on but couldn’t read the time on his dancing, leaping watch.

‘Christ,’ said Loyal, holding the jerking arm and seeing ten past two. Which two? Two in the morning after the cave-in or twenty-four hours later, the next afternoon?

‘Cucumber, you think it’s afternoon or 2 A.M.?’ And looked at Cucumber spraddled, arms pressed against the rock to take the weight off his feet, head down. Cucumber turned his head toward the light and Loyal saw the blood tracking from black nostrils, the wet shirt shining with blood, the water around Cucumber’s knees washed with blood. Cucumber opened his mouth and his pale tongue crept from between his bloody teeth.

‘It’s easier for you. You got no babies.’

Loyal turned the light off and there was nothing to do but stand and wait in a half swoon, listening to Cucumber bleed out drop by drop.

And now he knows: in her last flaring seconds of consciousness, her back arched in what he’d believed was the frenzy of passion but was her convulsive effort to throw off his killing body, in those long, long seconds Billy had focused every one of her dying atoms into cursing him. She would rot him down, misery by misery, dog him through the worst kind of life. She had already driven him from his home place, had set him among strangers in a strange situation, extinguished his chance for wife and children, caused him poverty, had set the Indian’s knife at him, and now rotted his legs away in the darkness. She would twist and wrench him to the limits of anatomy. ‘Billy, if you could come back it wouldn’t happen,’ he whispered.

He came awake with a shout, dipping into the water. He could not stand. His clubbed feet could not feel the ground. He knew he had to get the bursting shoes off, the leather that clamped the flesh, the tightening strings, if he had to cut them off. He crouched, gasping, in the water and felt his right shoe. The puffed leg bulged over the top of the shoe. He pulled at the laces underwater, worrying the wet

knots, racked with shudders. After a long time, hours, he thought, he pulled the lace free of the eyelets and began to lever at the shoe. The pain was violent. His foot filled the shoe as tight as a piling rammed into earth. Christ, if he could see!

‘Berg. Berg, I got to put on my light. I got to get my shoes off. Berg. My feet’s swole up wicked.’

Berg said nothing. Loyal switched on his headlamp and saw Berg leaning against the wall, halfsagged into a tiny shelf where his knees rested, bearing some of his weight.

He could barely see his shoes under the cloudy water, eighteen inches deep now, and the shoe would have to be cut off. He stood up and switched the headlamp off while he fumbled for the knife in his pocket. It was hard to open it, and harder to sit back down in the water – fall down – and cut the tight leather open. He used the lamp as little as possible while he sawed and panted and moaned. At last the things were off and he threw them out into the blackness, the soft splashes, Berg to his left groaning. His feet were numb. He could feel nothing.

‘Berg. Cucumber. Get your shoes off. Had to cut mine off.’

‘Eh-eh-eh-eh-eh-too-eh-eh-eh

cold,’ said Berg. ‘Fucking

eh-eh-eh-eh

freezing. Can’t.’

‘Cucumber. Shoes off’ Cucumber didn’t answer but they could hear the blood falling into the water.

blood bloodblood blood blood bloodblood

It became difficult to talk, to think. Loyal had long, sucking dreams that he struggled to leave. Several times he thought he was sitting in a rocking chair beside the kitchen stove, and that a child was leaning asleep against his heart, light hair stirring in the whistling wind from his nostrils. He ached with the sweetness of the child’s weight until his mother stirred the fire, and said in an offhand way that the child was not his, it was Berg’s daughter, that these things had been torn from his life like calendar pages and were lost to him forever.

Then he would rouse Berg for the time, but the headlamps were dim and it always seemed to be ten past two.

‘Stopped,’ said Berg. ‘Watch

eh-eh-eh

stopped.’

‘How long we been in here do you think?’ He only talked to Berg now. He stood close to Berg.

‘Days. Five or

eh-eh-eh

four days. If you hear them we got to tap, let them guys know we’re still alive down here. Pearlette. Hope they-

eh-eh-eh-eh-ey

taking care.’

‘Pearlette,’ said Loyal. ‘She your only kid?’

‘Three. Pearlette. James. Abernethy.

Eh-eh

call Bernie for short. Baby. Sick every winter.’ Berg directed his feeble light at the wall. The water had gone down two inches. ‘We got a

-eh-eh-eh

chance,’ said Berg. ‘Anyway we got a chance.’

The dying headlamps pointed in Cucumber’s direction showed nothing. They called, with clacking jaws, but he didn’t answer. Cucumber was beyond the circle of light, silent.

When at last the sound of faraway tapping came they struck wet rocks against the wall and wept. Away in the darkness Cucumber rolled in eight inches of mine water, his mouth kissing the stone floor again and again as if thankful to be home.

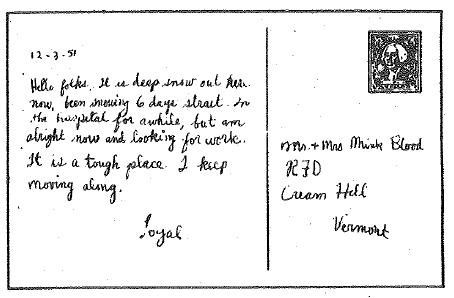

HE carried the Indian’s book around with him for years before he started to write in it. It had a supple cover, narrow bands of snakeskin sewed with a long-armed featherstitch. The pages had rounded corners. The Indian’s hand was impossible; pitching letters with open tops and long, dangling descenders, words jumbled into one another, omissions stacked on top of the sentences. There were strange lists. On one page Loyal read:

sacrifices

lamenting

hungering

jail

dream & vision

journeys

In another place the crooked sentences said: ‘The dead live. Power comes from sacrifices. Give me good thoughts, calm my rough desire, strengthen my body, do not let me eat any wrong food. The sun and the moon will be my eyes. Let me see white metal, yellow stalks, red fire, black north. Rotate my arms 36 times.’

Would the sacrifices be scalps, Loyal wondered under his cowboy hat.

The part about the dead that kept on living made him think of Berg and his idea about miners’ ghosts, about Berg’s daughter the way he had imagined her, realer than anything Berg had said. Berg’s children, he thought, with the taste of snow in their mouths. And Berg himself, hobbling around somewhere now on aluminum feet. He’d heard that at the little hospital in Uphrates where they’d taken Berg a nurse had cut the laces on his shoes. She began to work the left shoe off. With a wet sound the shoe came away, and with it, adhering to the inner sole, the turgid, spongy bottom of his foot, baring the glistening bone. Loyal couldn’t remember if they had taken him to the same place. At least he could still walk well enough, at least he had not lost his feet or any of his toes, although the pain seemed locked permanently inside his leg bones.