Postcards (28 page)

Authors: Annie Proulx

The cook stood in front of the refrigerator. She held the door wide, showing the meat, the jars of West Indian pepper sauce, French mustard, Niçoise olives, capers, pinon nuts, walnut oil, quarts of milk and cream, half-empty bottles of white wine, waxy cheeses, endive and chicons, brown peppers, the great black grapes, the breasts of chicken.

‘Piano,’ Ben seemed to say. His voice shook deep and ruined. ‘Piano.’ Loyal could see past him into the living room to the painting like blood on the wall.

‘He says for you to go away now too,’ said the cook to Loyal. “The missus wants you to go. Wants you to leave. They both wants you to get out.’

‘Piano.’

In the studio Loyal saw that Vernita, the biologist of jellyfish, had ordered sea changes. All was drenched, swept away as by equinoctial rides. The walls were freshly calcimined a bitter white, the floor tiles scraped and washed and waxed until they reflected like red water. He read the message in the sheen of the aluminum kettle, spout tip like a cherub’s mouth. Books and magazines squared on dustless shelves, the bed stripped, window glass so clear it erased distance. He turned slowly. The curtains swelled, the empty sink gaped for a sweet gush of water, its faucets burning with light.

The mirror drew his eyes like a tunnel opening into another world. He had not looked in so long, still thought of himself as a young man, strong arms, the black fine hair and hot blue eyes. His face, he saw, had gaunted out. The blue mirror frame enclosed his fixed features. The ruddy liveliness, the quick rage of the eyes had faded. Here was the skin of the ascetic whose neck is never marred with sucking kisses, the rigid facial planes of someone who spends time alone, untwisted by the squinting disguises of social life. His eyes did not change when women walked past. It could be, he thought, that spark was finally dead. But did not believe it.

In an hour he was packed up and heading north in the truck. Age seemed at his throat.

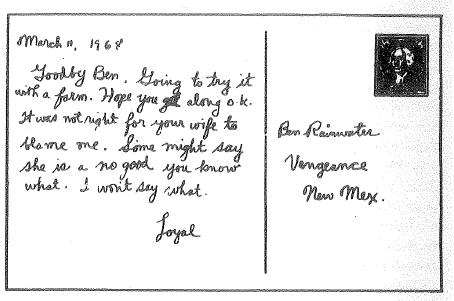

But the old urge for the farm was like the heat of a banked fire, the time was dipping down. Fifty-one years old. The prospecting, the barroom nights, the summers digging with Bullet, the climbs up to the passes in the mountains, moving through the breast-high rabbitbrush, his way had been that of an exile for a long time. He had tried to keep the tremulous balance of his life, walking a beam between short friendships and abrupt departures. He thought of the nights on the sand, the squalls of desert foxes, the stars screeling points of light cutting paths and orbits, the gaping core. And the shuddering hours with Ben in the observatory tracing sidereal arcs with the still camera, trying to follow Ben’s vaulting talk of distant energy and collapsing matter. Yet, reeling through corridors of galactic ice, chill remote starlight, could not completely forget the warmth of barn, kitchen, the spark-furred heaps of peltry. Never was the mood of farm work closer than when Ben was ruined with drink, slobbering in the black swillbowls.

In Mexico City swaying before the statue of General Alvara Obregón with Ben slouched against him, the old longing swamped Loyal. On a granite pedestal below the statue the general’s arm floated in a lighted jar of formaldehyde. The yellow bone protruded from the flesh, and Loyal saw in the angle of the bone himself lying on his back in the bed, his hands behind his head, his elbows jutting up.

One of these days he would wake up dead. He had not yet made a start on the farm, on curing his trouble with earth, clacking hens and a dog springing up with muddied feet. He imagined a family of silvery children and warmth in the bed, a voice in the dark instead of the forceful stars and the Indian’s silent book.

The limb swam in ichorous fluid and as he studied the naked ulna he knew it was late in the day to get out, late to buy a farm, never mind the rest of it, but he knew that he had to do something or burn his money in the stove. Maybe it would work for him. Maybe Vernita did him a favor. Why had he stayed so long?

Kiss the little adobe studio good-by, kiss good-by to the freezing nights. And the stupid hours leaning on Criddle’s zinc-covered bar until Ben was ready to be hauled away.

SO THERE HE WAS, fifty-one years old and in North Dakota. The farm a curve of earth, a slat-sided house leaning into the wind, starved fields among the ranches and sugar beet farms. Why the hell was he buying this, he wondered, even as he pushed the bank check at the vulture-wattled man in the sheepskin coat. Imprisoned in his mind, like an iridescent beetle in a matchbox, was the image of his slanting field crowned by scribbled maples, not this bony square of dirt. He didn’t even know what he wanted to do with it.

Half an hour later on the street he saw the wattled man in his truck, leaning his head on the steering wheel as though resting a little before he drove off.

He couldn’t think of it as his farm, and called it ‘the place.’ That’s what it was, a place. He didn’t know what he wanted to do, grow sugar beets, soybeans, wheat – the County Agent had mentioned the new kinds of Durum, Carleton and Stewart, good grain quality and resistant to stem rust. The machinery was expensive. He could run cattle or raise hogs. There was money in cattle, but you had to be born to it he thought. He only knew dairy farming, pasture, hay, woodlot, some crop management. It wasn’t that kind of place. Things were different in farming now. He bought fifty barred rocks while he thought about it. He could go into poultry. Or dry beans or peas.

It was not a good place to sleep at night, that metal bed, paint chipped iron, sheets trailing on the floor. An uneasy house. There was always a fine grit on the linoleum, soil blown from across the world, brown roils that rose from the steppes of central Asia and ended lying on his windowsills. The plate on the table made a grating sound. He’d picked up a persistent cough; the dust was irritating his throat.

In the back of his mind he had believed and not believed that the work of a farm would set him right. His trouble seemed to shift rather than repair. He woke up one night after a dream of Ben, but a far younger Ben, melting under his hands, rounding into a woman, the gaping stitchery where his sex had been, the face of the whore in Criddle’s showing her smeared eyes and coyote teeth. Thrashing awake he felt burning weals the size of pancakes on his neck and buttocks, his forearms. In the mirror his black fine hair, threaded with white, was shrinking back from his forehead. He still had his anger, hot as new blood. And hated it in himself.

It was three miles west to the next place, Shears’s hog farm, a huddle of buildings scraped together by a careless stick. He ran into old man Shears with his feed cap matching his white hair and the mustache fringing a juicy mouth, at the feed depot. From a distance somebody pointed out the two wheat-colored oldest sons, Orson and Pego, farmers whose land butted onto the father’s at the west. The hired hand, Oyvind Ruscha and his family of boys, swung in and out of a mobile home set beside the road.

Old Shears was full faced, tobacco chewing, violently progressive about new farm machinery. He urged Orson and Pego to go in

together on an air-conditioned, self-propelled combine.

‘Get it with the eighteen-foot cutter bar. Get the safety-glass windows and air condition. Tell him you want the lubricating bearings and the new V-belt and pulley drives. Get it as big and strong as you can. That’s the way it’s all going, big, quick machinery. You don’t have that stuff you don’t got a chance in hell of makin’ it in farmin’.’ They added a windrow pickup attachment. When it was delivered the old man tried it first, praising the smooth gear and speed shifts.

‘That son of a bitch can harvest anything you grow, wheat, oats, barley, flax, peas, rice, clover, alfalfa, soybean, hay, lupine, sunflower, sorghum or weeds, and them two can grow anything it can harvest.’

‘Yeah, especially the weeds,’ said Orson, the family joker. Loyal liked him. Reminded him of Dub. He’d write to them at home one of these days, let them know he had a farm.

The woman at the drugstore where he got his cough medicine told Loyal stories about the other Shears son, the youngest, who came back from the Vietnam War so misanthropic in spirit that he’d moved into a shed and took his meals from plates of bark, eating with a pointed stick or an old bayonet, she said, still stained with blood.

The drugstore was a crackling metal building hunched beside the Farmers’ Cooperative Bank. The woman’s shape was as formless as poured sugar. Two strange front teeth like the points of knitting needles clashed at her lip. ‘He don’t help out on the farm. He’s just holed up back there. Shears said he was gonna starve him out. So, they didn’t put any food out for him for a week. But Mrs. Shears couldn’t hold out and she was slippin’ a plate out there every night when she went to feed the hens. Now they got him goin’ regular over to the VA hospital in Fountain. Say it could take years and years to straighten him out.’

Every time Loyal drove past Shears’s farm he glanced at the shed and hoped for a sight of this specimen.

He thought he might grow sugar beet. The County Agent leaned hard on sugar beet. There was good high-yield hybrid seed now, resistant to curly top and downy mildew. When old Shears heard he was thinking beets he warmed up.

‘O.k., here you got a real choice which way you want to go on

your beet harvest equipment. You can go two routes. Your first route is your harvester that does in-place topping. It comes along, see, and cuts the tops off while the beets are in the ground. Then she’s got two wheels that point in toward one another, dig into the soil, loosen and lift out the beets in one operation. The kicker wheels clean ’em off and your rod-chain elevator carries ’em back to the beet wagon. That’s one way to do it. The other way, and the way I’d go, if I was you, is the harvester with a wheel, a spiked wheel, that lifts the beets out of the ground – the tops are still on. There’s a pair of stripper bars that raise the beets off the spikes and your pair of rotating disks cuts the tops off at the height of the lift. Then they go back to the trailer. It’s simpler. Man, I raised sugar beets back in the old days when the goddamn leafhoppers would wipe you out and what was left you had to get in with hand labor. Wouldn’t do it again. No way, José.’

Loyal saw the sign

FREE PUPS

propped against Shears’s mailbox. He had not had a dog in all the years since leaving home. Did he want to start now? It seemed he did.

He pulled into the yard, watched it fill with dogs, the plumy-tailed mixed-breed bitch, part English sheepdog, part German shepherd with a dash of collie, showing her teeth and growling, four half-grown puppies racing from the side door to his truck. Shears’s truck was not there.

He sat a minute studying the dogs. The door of the back shed opened and there was Jase, strange from his journey through the mountains of Vietnam. Talking to himself. Looking away from Loyal, away from the dogs, his blue-circled eyes skirting the edges of the buildings, slipping along the edges of clouds to motion on the ground, a bird, a car on the highway. Tall. Thin and stiff as a music stand, hardly twenty-one, with hair so light it looked silver. Now his flickering glance shot from one puppy to another, his mouth hung open with the effort to keep them all in sight. He pressed his chin down to his breast, wrenched his mouth to one side. Loyal hung on the truck door, marking out the pups he liked. There was only one after all, a quick-witted bitch who dipped through the snapping feints

of her littermates, squatted near the truck tire to piss, and got behind Jase, out of his sight until he whirled.

‘Guess that’s the one I like,’ said Loyal. ‘Can I offer you something for her?’

Jase threw his head back until his Adam’s apple strained white, tried to speak and faded, the words jerking at his mouth, tautening the cords in his straining neck.

‘All – all – all – the rest of them,’ and, in a rush of jammed syllables, ‘overatthesitefortheMcDonald’s. Neeeeee – ar thecrossroads. Building it. McDonald’s.’

Loyal crouched and made kissing noises at the pups. They rushed at him, laughing in his face, their hot paw pads and sharp nails paddling at his knees. He picked up the smart girl and put her in the truck on the floor.

‘Obliged to you,’ he said to Jase. ‘Stop over some time. Have a beer.’

‘Ah – ah – ah.’

The pup was on the seat, scratching at the glass.

‘Down. Down Little Girl, down Girly.’ He knew dog names should be short and crack in the mouth like ‘Whip’ and ‘Tack’ and ‘Spike’ but this was better. Little Girl. They drove away, the puppy lunging at the steering wheel as Loyal turned it, biting at the wheel and growling small growls until the jouncing stunned her into sleep, curled in a knot of sunlight.

At night on the ploughed prairie the darkness was darker than the Mary Mugg which at least had been illuminated by those blue and orange tracers of light that appear even behind closed eyelids. This darkness was thrown into deeper ink by the sprays of stars, asteroids, comets and planets trembling above him as though in a sidereal wind. As far as he stared across the fields there was no yellow window, nor crawling headlights pitching across the waste. The stars flooded him with longing for Ben, the great lover of cold points. Probably dead by now. The stars were not steady; they shuddered as though in a black jelly. That was the wind, the laminated streams of air flowing above the earth like distorting fluids, the silt-stippled wind wrinkling the distant astronomy.