Postcards (27 page)

Authors: Annie Proulx

Jewell walked out to the strawberry bed behind the collapsing house early in the June morning and pulled the nets off the dark rows. She would get a head start on Mernelle. Quack grass choked the rows and something had gotten under the net and eaten the berries on the end plants. She remembered worse: the hailstorm that made strawberry jam in five minutes, the loose cows trampling the plants. She spread her piece of carpeting on the cool soil and began to pick, setting the full baskets under the shady rhubarb leaves as she went. The sun heated up quickly, the baking soil shimmered with heat waves. By the time Ray dropped Mernelle off she had stripped the plot of ripe berries and replaced the nets for another picking in a few days. The black oil was in her cracked fingers.

She sat in the rectangle of shade behind the trailer in an aluminum-framed lawn chair, Mernelle sat a few feet farther out for the sake of the sun. The marigolds blazed. Mernelle’s arms and legs were the color of pecan shells. The black, long hair was teased up and twisted into a puff. She wore an orange playsuit. Her voice flung high words. But she was good-tempered.

‘I’ll make that strawberry-rhubarb pie for Ray if you can give me some of your rhubarb. Ray can eat a whole pie at one sitting.’

‘Well, I don’t blame him. You make wonderful pie. Sure, take all you want of the rhubarb. There’s plenty. And strawberries. Ought to do another picking next week. There’s so many this year I can’t begin to deal with ’em. And it seems like I lost my taste for strawberries. There was a time I could eat anybody under the table with strawberry shortcake. Jam. Just strawberries and cream.’ Jewell’s fingers were red to the knuckles with hulling the heavy berries.

‘Did you wash these. Ma?’

‘I rinsed ’em under the spigot out back. You can see they’re wet.’

‘I can see they’re wet but they feel gritty.’

‘You must be workin’ on the ones at the bottom of the basket. Dub. Dub was the only one of you kids could never eat strawberries.

He’d break out in a rash – strawberry hives your grandmother called ’em. Old Ida. Any kind of a rash she called some different kind of hives. Mosquito bites? That was “skeeter hives.” Get in the nettles you got a case of “nettle hives.” Your father’d come in from pitching hay up into the haymow, all that chaff down the back of his neck and he’d itch just wicked and you know what that was, it was “hay hives.” First time I heard that I bust out laughing. “Hey-ho, Mink has got the hay hives!” She didn’t talk to me again for some time. This is before we was married. Quite the old hen, I thought. She’d say all hoity-toity, “I don’t b’leeve a person ought to be held up as a figure of amusement for what they say.” But she had to put up with plenty. Old Matthew, he was a miserable old cuss. Temper! That’s where your father got his temper, and Loyal, too, I daresay. I see him one time, old Matthew, ask your grandmother something, wasn’t very important, just something about where something was, if she’d seen it. She was rattlin’ some pot lids at the time and didn’t hear him. She got a little deaf as she got older. Lost most of her hair, too. Used to wear a switch up in the front that was a different color than the rest. Sort of a rusty brown color. Well, he took it the wrong way, that she didn’t answer him and he flared up. Snatched up ajar of tomatoes she had standing on the shelf to put in something, and he held it out over the floor and just let go. The first thing she knew anything was wrong was this terrible smash right behind her, felt the wet on her legs, and looked around to see the tomatoes and glass all over her clean kitchen floor and old Matthew like a turkey cock with his face gobbled up so red. Yes, those old girls, they put up with a lot. It was considered pretty terrible to get divorced, so they put up with a lot, things no woman today would put up with.’

‘What about old Mrs. Nipple. You never would tell me what happened to her. You know.’

‘I have to say, though, old Ida was wonderful with the desserts. Made Queen of Puddings for Sunday dinner with raspberries – your mouth would almost faint it was so good. Apple puffets, plate cake. And the ice cream if she could get the boys to turn the crank. She made rhubarb ice cream. I know it don’t sound good, but it was. Same with the Concord grape. Ice cream if the grapes made it. If we didn’t loose them to a late spring frost.’

‘Quit stalling, Ma. I heard all that. What about Mrs. Nipple?’

‘She had a hard life, but kept her humor, I don’t know how.’ The dark cone of strawberries rose higher in the bowl. The white dotted undersides of the caps strewed the grass where they had thrown them. ‘I wouldn’t of cared to have been her. I used to say that to myself, “Thank god I’m not so bad off as Mrs. Nipple.” But in the end maybe I wasn’t no better off. The way things fall out is funny. Life twists around like a dog with a sore on his rear end that he bites at to make it stop plaguin’ him.’

‘That’s a nice picture, Ma.’ Mernelle itched to plunge her hands into the berries, lift handfuls high and squeeze until the juice ran down her arms. Unaccountable and strange wish, like her longing for children. They had the dog, she thought derisively.

‘Well.’

‘Mrs. Nipple.’

‘You probably don’t remember her husband, Toot, he died when you weren’t more than five or six, but he was a big, good-lookin’ man when he was young. Brown straight hair that fell over his eyes in a certain way, real nice eyes with dark lashes, sort of aquamarine color.’

‘It’s funny but I remember his eyes. He was a fat old slob and I was just a little kid but I remember his eyes. They made an impression on me. A strange color.’ And remembers the old man rubbing his hand over her heinie when she was on the ladder in the barn. I’ll give you a boost up, he’d said, and then the hot fingers.

‘When he was young he was a big fellow, quick and clever, a terror on the dance floor. He wasn’t a fat slob then. Good-lookin’. He’d joke, had an easy laugh and got along good with everybody. Girls was crazy about him. Called him Toot because after he’d been tomcattin’ around he used to say, “Guess I been on a toot.” He married Mrs. Nipple, of course she was Opaline Hatch, then. But soon became Mrs. Nipple and nobody could figure that one out because he kept right on like he wasn’t married at all, dated girls, went out every night. Mrs. Hatch, that was Opaline’s mother, had a big smile for everybody at the wedding. But Ronnie was born about three months afterwards so we had a good idea of what the attraction had been. It was a funny thing, she never got mad at him for all his hellin’ around. He’d come

draggin’ home drunk and smelling like he’d been dipped in throw-up and perfume, both, and she’d fix him something for his stomach and make excuses for him the next day to whoever he was workin’ for, that’s before they moved onto the farm. That farm passed to her from her family. Toot’s folks didn’t have a pot to piss in. It got so he depended on her for an awful lot. She got to thinkin’ she’d tamed him down, that life was finally evened out for her. Maybe he thought so, too. And that’s when it turned on ’em and started to bite.’

The naked, bleeding strawberries lay in the smeared bowl. Jewell reached for another basket and set it in her lap. Her fingers darted at the strawberries, plucking their crowns with cruel pinches.

‘What happened was when he was around forty-five, forty-six he got cancer of the prostrate. The doctor told him, “We can take the cancer out but you’ll be impotent. Or we can leave it alone and you’ll only have another six months or a year to live. You’ll have to decide.” Well, he decided to have the surgery done. And he

was

impotent. He was that kind of a man, you know, where that was the most important part of life. He went cold, then. He wouldn’t even put his arm around Mrs. Nipple any more, wouldn’t joke with the ladies like he always done. Wouldn’t touch any of them in tenderness or affection. It was as if he’d turned impotent all over. See, the touching was all connected with sex for him. Then he started in on suicide. He’d talk to her about it at supper. He wanted to kill her, then himself. Wanted to take her with him. “Tonight,” he’d say while they was eating the string beans and the hamburger patties. “We’ll do it tonight.” Always at suppertime. He done this for six years. She stood by him, I’ll say that for her. Short of giving in and letting him shoot her, she stood by him. He finally hung himself. It was after that Ronnie moved back to the farm. He never got along with Toot and lived over at his aurnt’s place from the time he was about fourteen. And I pitied her so bad, that her life had taken this terrible turn. And when it came at me in the same way I felt like … I still can’t say what I felt like. But I know one thing. You’re never ready for when it turns on you and goes for the throat.’

Mernelle held a strawberry in her hand. Her fingers folded, she squeezed. She threw the clot in the grass, glanced at her red palm.

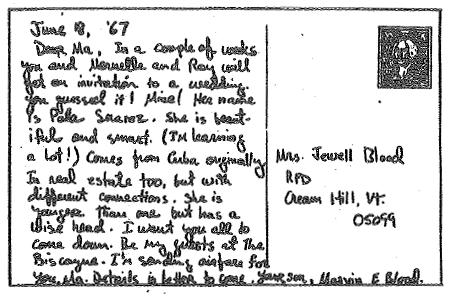

SHE WAS CLEAR about what she wanted. Looking at her ivory face, her black oval eyes, he felt himself the fool again. She had the thick little Cuban arms and a crooked nose, but there was a cool glaze he loved. The quick hands moving while she talked, the hurrying voice drew him to her.

‘I want this secretary job to learn more about real estate. I want to understand the fine points, get familiar with the names and the ideas of the big investors from New York, see how you make things work.’ He nodded. She wanted his secrets.

‘But a year from now I will be ready for a bigger position. I am very ambitious.’

‘I can see that, Miss Suarez. What type of real estate interests you – residential properties?’ The women in real estate all worked with houses.

‘I am more interested in the special commercial properties – centrally designed, landscaped projects that balance hotels, shopping malls, marinas and services in a beautiful and coherent way. Spaces with water elements, plants, esplanades, open-air restaurants. That is why I applied here. I have studied urban architecture and I admire many of your projects. Spice Islands Park. Enchanting, those ziggurat offices and shops built around pocket parks of fragrant trees. The lovely rooftop gardens, the flower balconies. All soft colors. And everybody wanted to work there right away. I know the architect you worked with well. He is my cousin. No other “American” real estate developer would think of using a Cuban architect.’

She was so serious, he thought, leaning a little forward in her grey silk suit, her stubby hands folded on her knees. The hair was plaited and the plaits wound sleekly around her head. Her ivory skin was a little rough with old acne scars – it gave her a tough and interesting flavor that he associated with the name ‘Mercedes’ for some reason.

‘I can be useful to you, too,’ she said. He knew that.

‘There are many invisible Cuban millionaires in this city. There are banks and bankers, a whole society that the American establishment in Miami ignores. In that world we have our own ideals and thoughts, our own television and radio, a certain style, a way of thinking and walking and talking, holidays, celebrations and balls, charities and school curricula utterly unfamiliar to your world. I can be your bridge to that society. If you are interested, of course.’ She was so serious.

‘No,’ he said. ‘You cannot have the secretarial job. But I just realized that I am looking for someone to fill the position of Director of Intercultural Marketing and Development. Perhaps you would care to apply?’

When she smiled, he saw, in the white dazzle of pointed teeth, in the gold glint of a back tooth, that he had a pirate.

IN THE STUDIO a mirror hung over the sink. He looked in it only to shave, and over the months soap spatters, dust and flyspecks dulled his image until after the trip with Ben to Mexico City, a trip made not for any reasons of his own, but to haul Ben up out of the street swill when he fell. It was the worst he’d ever been.

They got back, after two weeks. He helped Ben, trembling and voiceless, into the big house through the kitchen door, guided him past the dishwasher, the chopping block, past the swaying strings of chili and garlic, the bouquets of herbs hanging upside down, the Spanish ham in verdigris mold dangling like a punching bag from the heavy wrought iron hook.