Postcards (22 page)

Authors: Annie Proulx

Corcoris’s hand was up.

ROAMING OVER THE DUSTY Colorado Plateau, following the Morrison formation to Utah’s Uinta range, to Wyoming into the Great Divide basin and up to the Gas Hills, across the Rattlesnake Range and into the Powder River basin, Shirley Basin, Crook’s Gap, scanning the uplifts, the salt washes below the slickrock marker beds, rim walking the Shinarump levels, watching for the brilliant orange and yellow. He’d sorted out the subtleties of the Geiger counter’s endless chipping, chipping, knocked around in the gritty bars and saloons. The electric feeling of quick money was everywhere. Christ. It excited him.

Crowded beside stinking desert rats to study the latest government anomaly maps. But wouldn’t you know, he was just in time for the

federal cutback. The buying station shut down, the price guarantees dissolved. The smart guys were using helicopters and planes, skimming along the mesas with fifteen-hundred-dollar scintillometers. The scratch-dirt prospector had a hard time. What the hell, he kept moving.

The prices picked up again, high enough so that this time the big outfits moved in on the low-grade ore. Yellowcake speculation. Talk was of production levels. The rock rats disappeared. It was all big business now, deep mines, acid leaching, chemical extraction, company prospectors, poison wastes and tailings, sand slurry choking the streams, big fish kids and mountains of dead and reeking tailings.

He was finding a hell of a lot of bones, knowing you found what you looked for.

The bones and seashells, stone trees drew him more than the idea of a big strike. Once he found three enormous weathered-out vertebrae at the bottom of a ravine. He’d thought they were stones. The Geiger counter threw up a storm of clicks. As he dug the first out he saw what it was. It was heavy, uranium rich. He drove around for weeks with the bones wrapped in newspaper in a box in the back, dunking about it before he went to bone-buying Donald at his South Dakota ranch-supply-bar-grocery store.

Donald the Bone Man, gink with a ragged mustache hanging over his puffed mouth, chin sliding away into neck, hair over the ears, escorted Loyal into the back room with a sweep of his pearl-button cuff. Scar like a socket in his right cheek, the ten-gallon hat, brim curled and crown dented just right, the long, long torso in its western shirt disappearing into faded jeans cinched with a tooled leather belt and a buckle ornamented with the setting sun behind a sawtooth range, but he would pay decent money for bones and better money if you drew a map of where you found them. What Donald got nobody was sure, but he drove a mint pickup traded in every six months. Donald would not change the oil. He wore handmade western shirts. Donald’s back room was stacked with boxes of bones where the archeologists and paleontologists from museums and universities back east pawed through them in the summer, asking Donald in wheedling voices for guides to the places where the choice specimens had been found. Donald was a checkpoint, a starting place for beginners.

Loyal saw the look come over Donald’s face; knew what he was planning; he’d sell these specimens for the uranium.

‘I want them to go to a expert at some kind of fossil museum. If I wanted to sell them for the uranium I could of done that myself.’

‘You could get more for them for the uranium.’

‘I want them to go to one of the guys that studies the fossils – so he can tell what wore these.’

‘Hell, I can tell you that. These here is from a duckbill dinosaur and I bet you found ’em over near Lance Creek. Plenty of duckbill skeletons over there. There and up in Canada in the Red Deer country, up in Alberta. Want to see what they looked like?’ Donald rummaged in a bookcase and found a grimy

Life

magazine with pink-faded color plates.

‘Look at this. There’s your goddamn duckbills.’ The illustration showed mud-brown beasts submerged to their chests. Dripping weeds hung from their muzzles. ‘That’s what you found. Crawled around in the swamps. Too heavy to walk around on the dry land so it had to float in water. Suckers were more than thirty feet long. Not real rare. You’d get more for the uranium in your samples. You bet.’

‘Mister, I come across a lot of bones out there. I don’t want these to go for fucking uranium. If that’s what I wanted to do, I’d do it. It’s the bones I’m interested in. I’m interested in these duckbill things.’

The splinter was a freak thing. There’d been an old wooden box in the back of the pickup for years. He’d tossed ore samples and rock hammers into it until the sides broke and the ends fell out. Collapsed on the truck bed it was only the echo of a box. The rocks, bones, tools and pipe rolling around in the truck could be heard a mile out on the plains.

‘Damn noise drive you nuts.’ He swerved up into a setback shaded by cottonwoods. He’d make camp early, straighten out the mess in the back of the truck. He laid into the mangled box with the heel of the trail axe.

‘Good enough to make coffee even if you ain’t good for much else.’ As if stung, the box shot out a two-inch splinter that pierced

his right eyelid at the outer corner, pinning the lid to the eye itself. The pain was extraordinary, a rod of agony. He stumbled to the driver’s seat and looked in the rearview mirror with his good eye. He didn’t think it was in too deep. There was a pair of vise grips on the dashboard. He would have to pull it out. He would have to drive the sixty-something miles to Tongue Bolt where there was some kind of a clinic.

He didn’t let himself think about it, but set the vise grips, held the lid with the trembling fingers of his left hand and clamped onto the protruding splinter in awkward pain. He smelled the metal of the vise grips, felt the fast beat of his blood. He gauged the angle of the splinter’s entrance flight then jerked. The hot tears streamed down his face. He hoped it was tears. He’d seen a dog hit in the eye once and the fluid drain from the collapsed ball. The pain was bad but bearable. He leaned his head back and waited. He couldn’t see a damn thing from that eye. Maybe never would.

In a while he opened the glove compartment and got out the box of gauze. The box was dog-cornered and dirty from kicking around for years with spark plugs and matchboxes, but inside the bandage was still coiled in the blue paper. He covered his eye, wrapped the bandage around his head, looping behind his right ear to hold it in place. He started the truck and drove out toward the highway. Through blurred, monocular vision he was conscious of driving through a reddish haze. The dust the truck had raised on the way in had not yet settled.

At the clinic, glass door, stick-on letters. The waiting room was full of old men with hands folded over sticks, looking him over expectantly. A girl behind a glass wall with a sliding panel. She opened the panel. Curly hair, eyes shaped like squash seeds.

‘Nature of your problem?’

‘Got a splinter in my eye. Pulled it out. Hurts like a bastard.’

‘You just sit down. Dr. Goleman will get to you pretty quick. ’Nother emergency in there right now. Every time on Men’s Clinic day it goes haywire. You’re our third emergency today. First we had a woman opened the door of her station wagon and broke off both her front teeth and broke her nose, young woman, we had to get the dental surgeon over, now we got a man that one of his workers

cut his fingers off with a shovel digging dinosaur bones, and you, and we’ve still got the afternoon. This is a doozy of a day. And some of the regulars for the Men’s Clinic been sitting here for over two hours. Can you fill out this form, or do you want me to read it to you and you give me the answers?’

‘I’ll manage.’

But he wrote only his name, then sat with his head back counting the hard painful beats of his heart behind his closed eyes until the old man next to him shook his wrist.

‘I was raised in this country,’ he whispered. ‘My old dad was a surveyor. Come out in the old days. Twelve children and I was the third. I’m the only one left. Want to hear something funny? Tell you something very funny, and that was the way my old dad died. We was walking home in the dark to the cabin, me and my old dad and my sister Rosalee. I don’t know where the rest of them was. Rosalee she says to him, “Dad, how come we don’t see no lions or tigers around here?” Dad says, “There ain’t none around here. Lions and tigers they all lives in Africa,” and we goes in the cabin. Well, the next day my old dad goes out to survey a line somewheres way up in the mountains and he don’t come home when he’s supposed to. After a few days his wife, that’s his second wife who I never liked, says, “He ought to be back by now but he ain’t. I got a feeling something’s got him.” Well, she didn’t know how true she spoke. They found him up there with his transit and his flags and all layin’ on the ground. There was claw marks on his chest and the prints of a big cat all around. And Rosalee said, “It was tigers,” and you couldn’t never persuade her otherwise. What do you think of that?’

But Loyal did not speak until the old man shook his arm again.

‘They want you to go in now, buddy. Can you make it?’

‘You bet.’ But the floor dipped like a ship’s deck.

And in the other room saw a monster, left hand in a cocoon of bandage, feet in flapping basketball sneakers, a matted beard wet with the saliva of a swearing rage.

‘What the hell happened to you?’ It was the patient who barked the question, not the doctor, a faded man with the widest wedding ring Loyal had ever seen. Loyal told the splinter story in one sentence.

‘What a fuckup,’ said Bullet Wulff, ‘what a pair of fuckups,’ while Goleman sluiced the injured eye with a saline solution.

‘You can take off, Bullet,’ said Goleman, ‘instead of giving my other patients a hard time. But I’d like it if you hung around town for a few days so I can look at you again. The King Kong Hotel is comfortable enough.’

‘You bet it is,’ said Wulff clawing at his bloodstained shirt pocket with his good hand. He pulled out a bent cigarette and lit it. Most of the tobacco had fallen out and the paper flared up like a torch. He stayed on the table, watching Goleman lave the eye.

‘You’re lucky, Mr.—’ Loyal could feel the heat of the lamp, smell the doctor’s stale breath.

‘Blood. Loyal Blood.’

‘You’re lucky, I think.’

‘That’s good. I never been this lucky, run a splinter into my eye.’

Wulff laughed. ‘That’s telling him. Hey, do you like crab legs?’

‘Don’t know. Never had any.’

‘Son of a bitch! Never had no crab legs?’

‘Please don’t talk,’ murmured Goleman, pressing close to Loyal and peering. Finally he put a plastic flesh-colored patch over the eye, the patch secured by an elastic cord that pulled viciously at his hair.

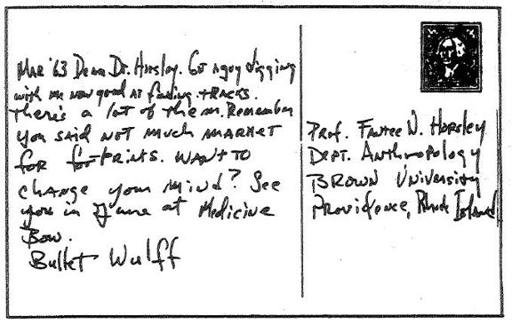

‘Crab legs are Alaska’s gift to the human race. The King Hotel gets king crab legs – think that’s why they call it the King Hotel – flown in frozen twice a week and they fix those suckers up would make your granny whistle Dixie. You will think you died and went to heaven. I hereby invite you to come to supper at the King with me. For the crab legs. Croix de Guerre. We’ll talk about our war wounds. We’ll compare trades. You can tell me about uranium and I’ll talk dinosaur bones. I’d ask you too, doc, but you always want to talk about bowels and fistulas.’

‘You know something about dinosaurs?’

‘I know something about dinosaurs? Tell you a little secret – nobody knows nothing about dinosaurs. Crazy ideas, wild theories, hot-shot guys oughta think up movie ideas. I heard ’em stand in front of a sandstone cut, put their fingers up their ass and scream. They guess, they fight, they get snakebit, they haul heavy stones

by hand for miles. They run the other guys down,’ throwing his eyebrows up and down like Groucho Marx. ‘That’s what I do. I hire out to the guys from the universities and the museums. I find fossils, I dig ’em, I ship ’em to the paleontologists back east and let them figure out who ate who and how many teeth they needed to do it and what Latin name to slap on ’em. They write me letters all winter, great hands for writing letters. Then they come out in the summer with their assistants and graduate students. I’m the one makes the coffee. I’m the one that plasters the blocks and gets ’em loaded on the truck. I’m the one that crawls into the caves. You want a job? Make a nice change for you. The guy that was diggin’ with me better be crossin’ the California state line by now or he is goin’ to be dead meat tomorrow. Had about as much idea of what he was doin’ as a cog railway conductor at the ballet. We oughta be a good team, One-Eye and One-Paw. Maybe get up some kind of a sideshow act and not have to work no more.’

Over the crab legs, swallowing the sweet meat, Loyal talked about uranium rambling, geologists and pitchblende, the way the mining investors were all over.

‘Like stink on shit,’ said Loyal. ’When I started out on the Plateau it was rim walking. You’d find the right beds, you’d know your background count and get out on there and walk along, old Geiger counter nipping along. Another good way was to get down below the cliffs and check out the rocks that had fallen off. That’s how Vernon Pick found the Hidden Splendor deposit. He didn’t know nothing about prospecting, he was sick, just about broke, worn-out. Stopped to rest at the bottom of a cliff and seen his counter licking off the scale. Turned it down to a lower setting, she’s still off the scale. Knocked her down to the cellar notch and it’s still right up there. For a minute he thought the counter was broken. Then he figured out the rock had probably fallen off the cliff face, so up he climbs up with his counter and he finds it. Today Vernon Pick is uraniumaire. Sold it for nine million dollars.