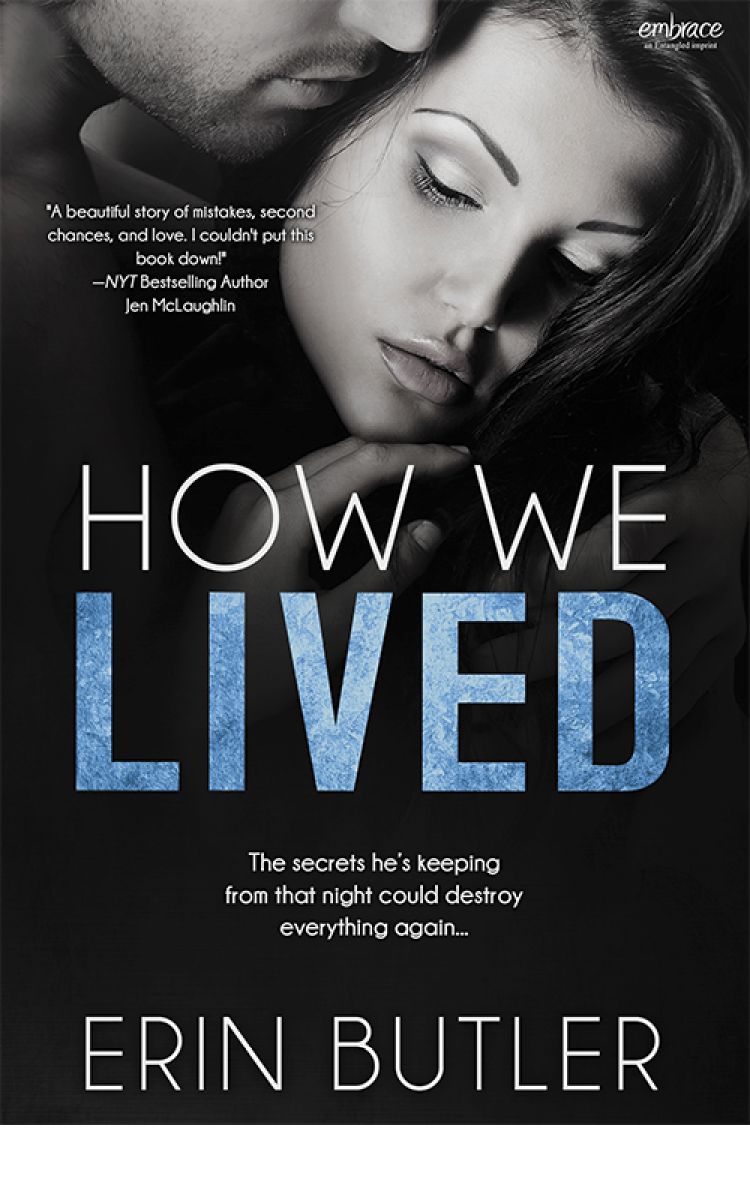

How We Lived (Entangled Embrace)

Read How We Lived (Entangled Embrace) Online

Authors: Erin Butler

Tags: #tammara webber, #cora carmack, #jennifer armentrout, #forbidden love, #jamie mcguire, #new adult, #contemporary romance

The secrets he’s keeping from that night could destroy everything again…

Nineteen-year-old Kelsey Larkin’s parents uninvited her to her brother’s funeral. She just wanted to wear jeans and a T-shirt—the clothes Kyle would’ve wanted her in—not wrap herself up in death. So she watched the funeral from afar, like an outsider. Which is just how she feels.

Chase came, though, just like she knew he would. Until a few months ago, the three of them had been best friends, and then Chase made a mistake that shattered both families. But when Kelsey looks at him, she doesn’t see her brother’s killer. She sees the boy next door who’s always taken care of her. She sees

home

.

When Chase tells her his feelings run deeper than friendship, she can’t help but get lost in him. In Chase, she finally has the closure she’s been unable to find anywhere else. But the boy she’s falling in love with is still hiding secrets about the night Kyle died. Secrets that could destroy everything they have…again.

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is coincidental.

Copyright © 2014 by Erin Butler. All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce, distribute, or transmit in any form or by any means. For information regarding subsidiary rights, please contact the Publisher.

Entangled Publishing, LLC

2614 South Timberline Road

Suite 109

Fort Collins, CO 80525

Visit our website at

www.entangledpublishing.com

.

Edited by Heather Howland and Kari Olson

Cover design by Heather Howland

ISBN 978-1-62266-182-4

Manufactured in the United States of America

First Edition April 2014

For Sarah, who is quite possibly the best sister ever, and who, after reading this book for the first time said, “You are dedicating this book to me.” Thanks for always being there and for being the one person who I know will get me, even when I don’t know if I get myself.

For Rich, my big brother, my “Kyle.” Childhood memories are made of the best stuff, aren’t they? Thank you for the memories that inspired me while writing this one.

Chapter One

-Kelsey-

Mother Nature was a bitch. Really. The whole world couldn’t give a crap about me right now. Or Kyle.

Kyle.

The name pinched my chest so hard I had to take another breath to swallow it down. Hidden beneath the shade of a huge oak tree, I drew my knees up and hugged them to my chest.

Kyle died five months ago, the weather in New England too cold to lay him to rest, the ground frozen and immovable. I once thought my parents’ relationship was as impenetrable as the solid, unyielding December soil. Apparently, I was wrong.

Down a little hill and off to the right, my mother and father sat in fancy white folding chairs dressed in head-to-toe black, stiff as the starch Mom used on their nice clothes—or more like two metal rods had been shoved up their asses. My mother pressed a matching handkerchief to the corner of each eye while my dad stared straight ahead. The distance between them was noticeable, palpable.

Mother Nature drew this whole fucking thing out. If we could have put Kyle in the ground when he died, maybe my dad wouldn’t be sleeping on the couch, maybe I wouldn’t need to take summer courses, and maybe I wouldn’t have had to sit under a massive tree in May while the sun streamed down through the leaves, watching my brother’s casket lower into the ground.

Sunny days were for lying on the beach, taking walks, and kissing boys. They were for happy things, not things that made you want to throw up your heart and toss it into the casket with everything else that had been taken away.

Fuck this. I was done. I’d mourned Kyle already. I hadn’t

stopped

mourning him. Was some stupid ceremony supposed to make me feel better somehow? Some stupid ceremony that drew out five months of grieving, five months of wondering where Kyle’s body was, five months of feeling like the world was continuously punching me in the gut? I moved to stand, but a hand on my shoulder pushed me down.

Chase

. I knew even before meeting his big brown eyes.

He was dressed in black, too. A suit and tie. Curls of dark hair wrapped around his ears, and shadows lined his face, but that wasn’t anything new. If anyone held true to the dark, brooding, reckless stereotype, it was Chase. In high school, the girls swooned so much they practically curtsied in his presence. Me? No effect. Not really. I was his best friend’s little sister.

Was

being the most important word. They weren’t best friends anymore, him and Kyle.

The pressure of his hand dragged me down, down, down. That hand. For twenty-one years it had picked Kyle up, but that night it threw back shots. It turned the key in the ignition. It clasped the steering wheel and numbly maneuvered through the snow and ice. It reacted too late when the car slid. When Kyle needed him the most, that hand was too late.

Chase killed my brother.

He was the reason Kyle’s body lay fifty yards away, shut tight in a wood box.

“Kels,” he said. His lips wrapped around the word, familiar.

Really? Kels? We hadn’t talked in months and my nickname dropped from his lips like it always had. I stared at his hand and tried to decide what to do. Slap him away? Pull him to me and hold him like I missed him? Because I

had

missed him, if that mattered, if that even made sense. He removed his hand before I could make up my mind and jammed it into the front pocket of his ironed suit pants.

“No one thought you’d come,” I said.

He nudged the two white carnations lying on the ground next to me with his shiny black shoes. “You did.”

The wind picked up and blew his hair across his forehead. It made him look ten years old again. He motioned to the spot next to me. Without thinking, I scooted over. And instantly regretted it.

We sat shoulder-to-shoulder, hip-to-hip, less air between us than the air separating my parents. Chase was always like that. He penetrated your personal space, not minding, and you weren’t supposed to mind, either. I moved over.

He acted as if he didn’t notice.

Down the hill, at the actual service, Mom had started shaking her head or nodding, depending on what the priest said. I couldn’t take it; I looked away and rested my head against the bark of the tree.

“You’re not dressed for a funeral,” Chase said.

The knees of my jeans were faded and thin, close to fraying. Would he understand? Mom and Dad sure as hell hadn’t. “I’m sick of wearing black.” I was sick of

feeling

black. I was sick of having to hold on to death so tightly because it was all I had left.

He let a piece of my hair slip between his fingers and drop. “You let your hair grow out.”

Uneasiness crawled over me. His gestures, movements, were the same as they’d always been. Like an old toy, or baby blanket, familiarity rang from him, calling to me. But his presence, his touch, shouldn’t calm me, it should make me furious. Instead of looking at him, at the boy I grew up with, at the boy I would have trusted with anything, I stared at his traitorous hands. “Are you going to spend the rest of this”—I pointed toward my brother’s grave—“crap performance making statements at me? If you are, you might as well head down there. I’m sure they’ll be thrilled to see you.”

I struck a nerve. I struck a damn major artery and I knew it. A part of me winced. I wanted to reach out and take the words back, but if I’d learned anything from the last five months, it’s that things weren’t reversible. There wasn’t some sort of cosmic rewind button for life.

His jaw tightened and an angry red blush crept up his neck.

The other part of me was pleased he was pissed. Good. That was for calling me “Kels” as if nothing had happened. That was for squeezing my shoulder as if he were still allowed to comfort me, as if I were still allowed to like it. It didn’t matter that I had.

He looked away and stared down the hill. Heads were bent in silent prayer now. A scowl crossed his face. “Your clothes…that’s why you aren’t down there, isn’t it? Which one told you you couldn’t?”

A lump formed in my throat and I swallowed. “Dad.” He’d been furious earlier. More mad than I’d ever seen him. Apparently wearing jeans and a T-shirt to Kyle’s funeral was a “disgrace.”

Chase muttered something and then leaned his head against the tree. “He always could be a prick.”

I propped my chin on my knees and hugged my legs tighter. I didn’t disagree because I couldn’t. Like most parents, he had his moments. Those moments just happened more often now.

Chase looked at me, his eyes like two hot red lasers piercing my skin. He opened his mouth, then shut it again.

“Stop,” I whispered. “Stop staring.”

Instant relief washed over me when he listened. I’d wanted to scream at everyone who stared at me these past months. They were waiting for me to crumble, all of them, their stares reminding me of just how close to the edge I balanced myself. One tiny misstep away from becoming one fry short of a Happy Meal.

For the next few minutes, we didn’t speak. Chase did his brooding thing, and that’s probably exactly what I looked like, too. Brooding could be fun. No one expected you to smile or be happy. They expected you to stare off into space looking upset. I was getting good at brooding.

When the soldiers in their dress uniforms hiked their guns into the air and fired, I flinched.

An honor

, I reminded myself, but it didn’t matter how many times I, or my parents, tried to convince me, this was wrong. Kyle had hated the army. Hated he’d signed up. Hated that he had to go overseas. He probably hated me right now because I let this stupid salute happen. It didn’t matter that I’d voted against it. Dad and Mom voted for it. My vote meant nothing.

Chase moved closer and dropped his arm around my shoulder.

Tears pricked, threatening to sneak out. People also needed to stop comforting me. It made things worse. I dug my nails into my legs for something to focus on.

After the guns stopped firing, a soldier stepped toward Dad and handed him the folded, triangle-shaped American flag. His head dipped, and he ran his fingers over the material.

I blew out a hard breath. This was harder than I thought, being here. It wasn’t just my own pain, it was seeing everyone else’s, too. “I miss him,” I whispered.

Chase gathered the hair that had fallen to the side of my face and moved the strands to the back. He looked away without responding. No “I miss him, too,” or anything. He only dug the heels of his nice shoes into the dirt.

That’s how I knew he’d heard me. Typical Chase Crowley. He never had words when things got tough. He spoke with his eyes, in gestures. I wasn’t going to because I’d probably lose it, but if I did look at Chase right now, I’d see deep, deep brown eyes, and a face so empty it mirrored my own.

With no help from the other, my parents stood. Like puppets of a perfect, proper couple, they hugged their guests and shook hands with the priest before walking off toward the car. For the first time, Mom peeked at me. She’d known I was sitting here. Known and cared, just not enough to invite me down to the actual service. “Embarrassing,” she’d said after Dad had already stormed out of the house.

In the midst of a cluster of headstones, she stopped mid-stride, her eyes popping out of her puffy red face.

She’d seen Chase.

I held my breath. It was like watching a raging fire burn toward a huge gas tank. “You should go,” I said, not really wanting him to. I just didn’t want Mom to go berserk. She wasn’t what you would call stable.

His voice was firm. “No.”

“Chase,” I pleaded.

“Kels, I’m not leaving.”

My father grabbed Mom’s hand and tugged her toward the car. He seemed to be saying something to her and I wished I knew what it was. They hadn’t been getting along. Well, unless they were both pissed at me, then they got along perfectly.

Chase waited until they were in the car and driving away before asking, “You didn’t ride with them?”

I almost laughed. If he’d heard their reactions to my outfit, he wouldn’t have had to ask. “Um…no.”

The cemetery workers started picking up, moving flower arrangements and folding chairs along with a rolled-up section of green fabric that was supposed to look like grass. I laid my head on my knees again and faced Chase. The movement made his hand fall from my shoulder. I’d forgotten it was there. No wonder Mom looked like she could maim him.

We stared at each other for a moment. I wanted to ask him why he’d come. I knew the answer; I just needed to hear him say it. I needed him to know I knew how much he cared for Kyle despite everything.

“I tried to see you,” he said.

Past tense, singular.

My linguistics professor would be so proud. “How many times?”

“Kels…” Again, my nickname dropped from his lips as if nothing had changed.

“Everyone tried, Chase. Everyone.” I closed my eyes and was barraged by images of the phone ringing, newspaper articles, crying parents, and Kyle. I quickly opened them. Living through the hell once was enough. I didn’t need to live through it again.

The brown in his eyes deepened. “I’m not everyone.”

My eyes blinked. I couldn’t close them because of the memories, and I couldn’t keep them open and see pain. Not Chase’s pain, anyway.

Everything inside urged me to comfort him.

Comfort him?

He said he wasn’t everyone, but that couldn’t still be true. But even as I was trying to convince myself, I knew it was. Chase could never be just anyone.

“Do you want me to say I’m sorry?” I asked. Though that was laughable. Me? Say sorry to him?

He shook his head, one curt, swift movement before grabbing the two carnations next to me. “What are we doing with these?”

“What else?”

His jaw ticked. “I thought we used weeds from your backyard.”

If I closed my eyes, I’d see a four-year-old me and two little six-year-old boys. Chase reminded me of the past, and right then I wanted to be anywhere but the future.

I shrugged and Chase stood, holding his hand out to me. I grasped his fingers and he hoisted me up, but I couldn’t leave our place under the tree. Not yet. Instead, I wiped at my jeans, removing any stubborn dirt. He waited, patiently, until I finally got enough courage to start down the little hill and toward the two gravediggers about to fill in Kyle’s hole. He ran ahead and stopped them while I stayed behind. The diggers, dressed in brown-stained jeans and shirts, turned to me and nodded. If they thought it odd the deceased’s sister wore jeans, a T-shirt, and sneakers to the funeral, they didn’t say anything.

At the foot—or the head, not quite sure which—a little metal marker stuck up from the ground. Larkin, it read, 1992–2013. The marker was temporary. Soon the headstone would be delivered with a stupid saying etched across the marble I hadn’t been asked an opinion on. They’d been in public face mode—formal and brief. There were no tears, no tissues. They picked the stone, they picked the design, they picked the saying, and done. Boom. Boom. Boom. We could’ve very well been picking out furniture for the formal dining room no one ever sat in.

It’d always been like that with them. When we were kids, my cat Snow White died. I was devastated my parents didn’t intend to give a cat a funeral. So Chase and Kyle gave me one. We stood outside at dusk, right after dinner, right after we knew we could get away without them noticing, and said good-bye to Snow White. Chase could make an unbelievably real trumpet sound, and since the boys played army with G.I. Joes all the time, they knew the song that played at military funerals. The lone trumpet one. Taps, they’d called it. We’d done the ceremony for every pet since then. Kyle’s cat, Tiger, Chase’s dog, Dippy, and even Hammy, their classroom’s pet hamster who accidentally went unfed for weeks in second grade. Stupid kid stuff, but Kyle wouldn’t want us to say good-bye any other way.

Chase handed me the flowers and then wrapped his hands around his mouth. The first three notes sounded and he held the last one until his cheeks turned red and deflated. After a pause, he continued, and I swear I never heard anything more beautiful in my life than that fake trumpet sound coming from his lips. My knees wobbled, dropping me to the grass. I couldn’t hold myself up any longer. I was sick of holding myself up.