Trigger Point Therapy for Myofascial Pain (12 page)

Read Trigger Point Therapy for Myofascial Pain Online

Authors: L.M.T. L.Ac. Donna Finando

Distal attachment:

Medial pterygoid:

medial (inner) surface of the ramus and angle of the mandible.

Lateral pterygoid:

the neck of the mandible below the condyle and the joint capsule and articular disc of the temporomandibular joint.

Action:

Medial pterygoid:

elevation of the jaw.

Acting unilaterally:

lateral deviation of the mandible to the opposite side (producing grinding motion).

Lateral pterygoid:

draws the ipsilateral side of the mandible forward.

Acting bilaterally:

protraction of the jaw, a movement necessary for opening the mouth widely; lateral movement (producing grinding motion).

Palpation:

Most patients with temporomandibular dysfunction suffer primarily from a muscular disorder that includes the involvement of the pterygoids. This muscle is rarely involved alone and is less likely to be tender than other masticatory muscles. The lateral pterygoid is one of the most commonly involved muscles in temporomandibular dysfunction. It is frequently overlooked as the source of the joint dysfunction.

Fibers of lateral pterygoid can be indirectly palpated through the masseter. Palpate with the mouth held open approximately 1 inch, or enough to relax the masseter sufficiently. Identify both the mandibular notch and the zygomatic process. Palpate just distal to the zygomatic process to identify tender areas of lateral pterygoid. It is frequently overlooked as the source of the joint dysfunction.

Palpate the upper fibers of medial pterygoid using a gloved finger inside the mouth. Slide the index finger lateral and posterior to the last molar. Identify the bony edge of the mandible. Move posteriorly and laterally to identify the medial pterygoid. Asking the patient to slowly bite down on a small object held between the teeth allows for clear identification of the contracting muscle.

Palpate the inferior fibers on the medial surface of the angle of the mandible. Allow the head to rotate slightly toward the side of the palpation to allow the neck muscles to soften. Reach up under the angle of the mandible approximately inch to identify the fibers of medial pterygoid.

inch to identify the fibers of medial pterygoid.

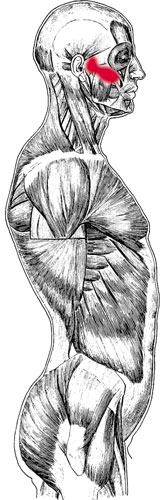

Lateral pterygoid pain pattern

Pain pattern:

Medial pterygoid:

Generalized pain in the mouth and the region of the temporomandibular jointâsymptoms include throat soreness, difficulty swallowing, painful moderate restriction of jaw opening; lateral deviation of the incisal path, generally to the contralateral side; some limitation of full range of motion, possibly limiting the insertion of two stacked knuckles between the teeth.

Lateral pterygoid:

Pain in the region of the maxilla and the temporomandibular joint that might be associated with arthritis of the jointâsymptoms such as temporomandibular joint disorders that include clicking of the jaw, restriction of the jaw opening, distortion of the incisal path, altered occlusion resulting in chewing dysfunction; excessive secretion off the maxillary sinus mimicking sinusitis; sometimes tinnitus. Note: Elimination of the zigzag of the incisal path when the tongue is placed on the posterior hard palate and the mouth is opened indicates pterygoid involvement.

Causative or perpetuating factors:

Medial pterygoid:

Forward head posture, bruxism, excessive gum chewing. Medial pterygoid is rarely involved alone and will be activated secondary to lateral pterygoid.

Lateral pterygoid:

As satellite trigger points to key trigger points in the neck muscles, especially the sternocleidomastoid; arthritis of the temporomandibular joint; bruxism; excessive gum chewing and nail biting; mandibular protrusion that might occur as when playing a wind instrument.

Satellite trigger points:

Medial pterygoid:

contralateral medial pterygoid, ipsilateral lateral pterygoid, masseter.

Lateral pterygoid:

contralateral medial and lateral pterygoid, masseter, ipsilateral temporalis.

Affected organ systems:

Digestive system.

Associated zones, meridians, and points:

Lateral zone; Foot Shao Yang Gall Bladder meridian, Foot Yang Ming Stomach meridian, Hand Tai Yang Small Intestine meridian; GB 2, ST 7, SI 18 and 19.

Stretch exercise:

Ask the patient to slowly open the mouth against mild resistance placed on the lower jaw. Hold the jaw against light resistance for a count of three to five. Repeat three times. Following this stretch cycle, open and close the mouth several times without resistance. Note: This may be used as a trigger point release technique as well as stretch exercise for the patient.

Strengthening exercise:

Due to the nature of this muscle, strengthening exercises are not necessary.

Stretch exercise: Lateral pterygoid

Â

Trapezius and trigger points

T

RAPEZIUS

Proximal attachment:

External occipital protuberance, nuchal ligament, spinous processes of C1âT12.

Distal attachment:

Spine of the scapula, acromion, lateral one-third of the clavicle.

Action:

Upper fibers:

flexion of the head and neck to the same side; elevation of the shoulder acting on the clavicle and the acromion.

Middle fibers:

retraction of the scapula.

Lower fibers:

depression of the scapula, rotation of the glenoid fossa upward.

Palpation:

The trapezius is the muscle most commonly found to have constrictions and/ or trigger point activity. To locate the trapezius, identify the following structures:

- ClavicleâFollow the curved course of the clavicle, from its articulation with the sternum to its articulation with the acromion. Medially the contours of the clavicle are convex; laterally its contours are concave.

- Spine of the scapulaâBony prominence of the upper scapula bounded laterally by the acromion, which forms the lateral tip of the shoulder girdle, and medially by the root of the spine of the scapula, the flattened, triangular surface located on a horizontal line with the spinous process of T3.

- External occipital protuberanceâLocate the base of the skull at the midline, just superior to the cervical spinous processes. Moving superiorly from the midline onto the skull, you come to the external occipital protuberance. Its most prominent protrusion is called the inion, or the “bump of knowledge.” Move laterally from the external occipital protuberance to palpate the superior nuchal lines, short transverse ridges that may or may not be palpable.

- Nuchal ligamentâIf the patient elongates his spine by pulling the crown of the head up and dropping the chin in toward the throat, you will be able to palpate the cordlike nuchal ligament connecting the spinous processes of each of the cervical vertebrae. When the patient is relaxed the nuchal ligament will not be readily palpable.

- Spinous processes of C1âT12âCarefully differentiate each of the cervical and thoracic vertebrae, understanding that C1 spinous process cannot be palpated.

Begin by locating C7 and T1, the most prominent vertebrae at the base of the neck. With the patient seated, place the middle finger of one hand on the most prominent vertebra at the base of the neck. This is probably C7; however, it may be C6. To differentiate the two, place your index finger on the spinous process above your middle finger; place your ring finger on the spinous process distal to it. Ask the patient to extend his head. By doing so C6 will appear to move anteriorly under the palpating finger; C7 will remain fixed, as will T1.

Once C7 has been clearly noted, begin counting spinous processes of the cervical vertebrae superiorly until you reach the spinous process of C2; then count the spinous processes of the thoracic vertebrae distally until you reach T12.

To palpate the trapezius muscle, begin at the superior nuchal line and follow the muscle distally toward the angle of the neck. The contours of the upper fibers will take your hands anteriorly along the free edge of the trapezius to the lateral one-third of the clavicle. Palpate for the quality and consistency of the muscle between the lateral clavicle and the spine of the scapula, moving toward the root of the spine of the scapula. Continue the palpation of the muscle distally as it narrows to its characteristic triangular apex at T12.