The Procrastination Equation (12 page)

Read The Procrastination Equation Online

Authors: Piers Steel

Retirement procrastination transforms the golden years into grim and gray poverty. It means living on skid row or with the kids, if you had them and if they'll have you. To prevent this from happening, governments have employed a few tricks. Tax breaks for contributing to registered saving plans are a good start, but to make the most of them, these breaks need to be accompanied by a definite deadline: that’s what procrastinators respond to. Stipulating that retirement contributions must be put aside by tax time is an effective strategy, as it breaks down long-term retirement savings into a series of yearly goals.

29

Still, on its own, it hasn’t proved to be sufficient, and so governments around the world are exploring another technique: automatic enrollment.

30

Applying the same negative-option marketing ploy used by mail order book clubs, employers can now

automatically enroll

their employees in pension programs with default investing options. Employees are free to withdraw or adjust their investment strategy at any time, but procrastinators will typically delay this decision, too. The result is a huge bump in enrollment.

31

Another neat trick comes from the trademarked

Save More Tomorrow

plan, developed by the behavioral economists Richard Thaler and Schlomo Benartzi.

32

Rather than automatic enrollment, they use a strategy that exploits procrastinators' tendency to discount the future: employees can choose

now

to save

later.

6c

That is, they must decide this year whether to start saving next year, and just as in automatic enrollment plans, once they have filled out the paperwork that commits them to saving, they will put off filing more paperwork to reverse their decision.

POLITICAL PROCRASTINATION

Governments, like people, have a bad habit of spending more than they receive. As I write this book, central government debts around the world are reaching commanding heights, often exceeding half the wealth their respective countries annually generate. By the time you are reading this book, it will be even worse. The United States, for example, will likely have finally hit the 100 percent mark, the point where it owes everything it makes in a year (that is, its total GDP). In dollar terms, that’s an eye-popping $16 trillion. How did we get so deeply in debt? Governments display the same intention-action gap that defines all procrastinators: they form intentions to stop spending but change their minds when the moment to act is upon them. The United States has repeatedly tried to curb its own spending by legislating a borrowing limit—essentially reining in the government credit card.

33

Unfortunately, this is akin to an alcoholic locking the door to the liquor cabinet but leaving the key in the hole. Politicians simply vote away their previous debt resolution and install a new higher limit, a process they have repeated

hundreds

of times.

Governments are perpetually focused on quick fixes that solve the issues of the moment; the urgent displaces the important. This isn’t a new insight. The American founding fathers understood this early on. I opened this chapter with a quotation from Alexander Hamilton, “Father of the Constitution,” featured on every American ten-dollar bill. Similarly, James Madison, “Father of the Bill of Rights,” wrote, “Procrastination in the beginning and precipitation toward the conclusion is the characteristic of such [legislative] bodies.” And regarding the threat of debt specifically, here is a revealing quotation from George Washington: “Indeed, whatever is unfinished of our system of public credit, cannot be benefited by procrastination; and, as far as may be practicable, we ought to place that credit on grounds which cannot be disturbed, and to prevent that progressive accumulation of debt which must ultimately endanger all governments.”

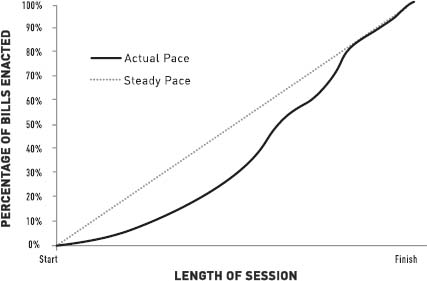

The American founding fathers were right; just take a look at the graph on the next page, which is similar to the two you have already seen, on student procrastination and the dillydallying of organizational teams. This one shows the average length of time it took the U.S. Congress to pass bills over the years from 1947 to 2000.

34

For every session in fifty, Congress passed the bulk of its bills toward the end of the session.

CONGRESSIONAL PROCRASTINATION

Though some bills are delayed due to political maneouvering, a large part of the delay should be due to procrastination. Furthermore, one can determine which groups are the worst procrastinators by comparing the surface area between the two lines—that is, between the steady work pace (the dotted line) and the actual work pace (the solid line). The more they are procrastinating, the greater the surface area. And Congress soundly beats out even the average college student when it comes to putting things off.

The result of all this procrastination is more than simply delay dealing with the national debt. All long-term national goals and challenges tend to be put off as well, no matter how threatening. The outcome of America’s War of Independence was partly determined by procrastination. In a key battle, George Washington crossed the Delaware to destroy a Hessian garrison: Colonel Rahl, head of the garrison, actually had prior warning of the invasion but decided not to read the report until later, after a card game he never had the chance to finish playing.

35

Winston Churchill and Dwight D. Eisenhower, both wartime leaders, explicitly struggled with procrastination in their own governments, which put off preparing for war with Germany and, later, the Cold War with Russia.

36

Today, the most pressing issue facing all governments is environmental depletion and destruction. We are in the midst of several ongoing ecological disasters, all projected to peak at the same time: 2050. That may seem far away, but environmental issues are like supertankers. They take so long to stop that they must be tackled decades in advance; by the time they are in your face, they can’t change course. Across the board, governments are putting off the issue until it is too late.

37

To begin with, the soil beneath our feet is eroding and depleting.

38

With about 40 percent of agricultural land already damaged or infertile, what will happen in 2050 when the little remaining arable land must feed over nine billion people? It is also doubtful whether there will be enough fresh water to grow the necessary crops; the projection is that 75 percent of countries will be experiencing extreme water shortages by that same date.

39

The sea tells an almost identical story.

40

Approximately 40 percent of oceans are already fouled and overfished, with species disappearing around the world. But it won’t get

really

bad until 2050, when the last of the wild fisheries are projected to collapse.

Interestingly—if that’s the right word—these environmental disasters make the debate over global warming almost superfluous. With so many catastrophes projected, the consensus is grim. Even the futurist Freeman Dyson, who doubts global warming, concludes, “We live on a shrinking and vulnerable planet which our lack of foresight is rapidly turning into a slum.” However, if climate projections hold true, we can expect about a three-degree increase in temperature by 2050.

41

No matter what country you are in, there won’t be any place that will truly benefit from this change. Entire ecosystems, like the Amazon rainforest, are expected to collapse, about a third of all animals and plants will become extinct, and billions of famine refugees will fight to determine who starves to death first. Since many of us will be around in 2050, it is worth taking a private moment to envision what this tomorrow will mean to you.

Government bodies have been alerted to this possible future for a long time. In 1992, 1,700 of the world’s leading scientists, including most Nobel Prize winners, signed the “World Scientists' Warning to Humanity,” which stated in the most explicit terms: “A great change in our stewardship of the earth and the life on it is required, if vast human misery is to be avoided and our global home on this planet is not to be irretrievably mutilated.” For even longer, we have known what to do about it. Unfortunately, we are procrastinating about translating this knowledge into action.

42

We could have avoided all these environmental issues if we had acted early. We can still mitigate them if we act now. The problem isn’t informational or technological; it is motivational.

Still, be thankful that government procrastination isn’t worse. Since the founding fathers of America were among the first to acknowledge the problem of procrastination, they did try to reduce its effects. Recognizing that what is expeditious can too easily prevail over what is wise, they tried to put temptation at a distance through

bicameralism:

legislation must pass through two houses or chambers. Using the exact terminology of “hot” and “cold” cognition favored by today’s scientists, George Washington explained to Thomas Jefferson why they needed a senate as well as a house of representatives.

“Why do you pour coffee into your saucer?” Washington asked.

“To cool it,” Jefferson replied.

“Even so,” Washington said. “We pour legislation into the Senatorial saucer to cool it.”

43

Aside from Washington advocating a scandalous breach of etiquette (as “to pour tea or coffee into a saucer . . . are acts of awkwardness never seen in polite society”), it is a solid strategy that has been widely adopted.

44

What can be initiated immediately will hold much, much greater sway over tomorrow’s better options. By purposefully building in delays, such as a sena-torial house of sober second thought, the Constitution reduces the effects of time. Since it takes longer to pass all legislation, bicameralism focuses decision making on factors other than whether an aim is immediately obtainable. In other words, the added delay of a second house ensures that everything is going to take a while.

LOOKING FORWARD

We live in a world where our impulsive nature is only appreciated by those seeking to exploit it. But this is beginning to change. The field of behavioral economics, which recognizes our capacity for irrationality, is being incorporated into governmental public policy. Recently, the Gallup Organization hosted the inaugural Global Behavioral Economics Forum. Events like this have started to draw the attention of economic and political leaders from all shades of the political spectrum; both British Conservative leader David Cameron and U.S. President Barack Obama are exploring behavioral economic solutions.

45

Phrases from Obama’s inaugural address highlighting this need for change appropriately resonate, especially our need “to confront problems, not to pass them on to future presidents and future generations.” Some of this thinking has already been translated into action, such as legislation making it easier for businesses to automatically enroll workers in retirement savings plans. Still, much more needs to be done.

As individuals and as a society, we pay a hefty price for our procrastination and have done so since the beginning of history. But we can bring millennia of dillydallying to an end today. A good start is to continue reading—the rest of the book is dedicated to actionable intelligence that puts putting off in its place. No matter what your procrastination profile—whether you lack confidence, hate your work, or are ruled by impulsiveness—there are proven steps you can take. And though we may have wished for this advice to have been available earlier in our lives, as we all know, working ahead of time is not really in our nature, is it? Perhaps we're now ready.

Chapter Seven

Optimizing Optimism

BALANCING UNDER- AND OVER-CONFIDENCE

A positive attitude may not solve all your problems, but it will annoy enough people to make it worth the effort.

HERM ALBRIGHT

I

remember few darker days of the soul than those I spent hunting for a job during a harsh economy. Job hunting is humbling—and humiliating—and it tests you to the very core. As rejections and months of unemployment add up, a gnawing uncertainty makes you doubt who you are. When bills mount so does the pressure to settle for less, to take that job you swore was beneath you. But then, when you finally lower yourself to apply, you find that even that possibility is out of reach. Here is where the value of faith comes in, whether in yourself or in a God with a plan. Against all facts and experience, you have to believe that the next interview, the next lead, or the next day will bring a different answer. Belief in oneself separates the successful person from the procrastinator; without such confidence, the couch beckons, the television distracts, and dreams of the future become what could have been.

1

Many procrastinators doubt their ability to succeed and as a result, stop making the effort. Once effort disappears, failure is inevitable.

Beliefs are powerful because they form or directly affect

expectancy,

making them a motivational keystone of the Procrastination Equation. As you become less optimistic or less confident in your ability to achieve, your motivation also ebbs: the more uncertain you are of success, the harder it is to keep focused. This self-doubt is usually associated with novel and difficult tasks, but it can also become a chronic condition: expectation of failure. Poor self-perception then becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy—by expecting to fail, we make failure a certainty because we never dig in and make an intensive effort. Since beliefs can create reality, we need a healthy dose of optimism to motivate us toward success.

On the other hand, too much optimism can also lead to procrastination.

2

Remember Aesop’s fable about the race between the Tortoise and the Hare? The far faster hare was so certain of his victory that he took a nap halfway through the race. The tortoise, moving slowly and steadily, overtook his slumbering competitor and won. As Michael Scheier and Charles Carver, psychologists who have spent their lives studying optimism, write: “It may be possible to be too optimistic, or to be optimistic in unproductive ways. For example, unbridled optimism may cause people to sit and wait for good things to happen, thereby decreasing the chance of success.”

3

Over-optimism is particularly prevalent when we estimate the time a task will take. It’s called “the planning fallacy.” Most people are not very good at predicting the length of time required for completing even commonplace tasks.

4

For estimating the time it will take to shop for Christmas presents, to make a phone call, to write an essay, the rule is “longer than you think.” I myself am making edits to this very chapter far closer to my publisher’s deadline than I'd like. We can’t really help ourselves; it’s a built-in bias of memory. To estimate how long future events take, we recall how long they took in the past. Our retrospection automatically abbreviates this time, and edits out much of the effort and obstacles. Unfortunately, this exacerbates the negative effects of procrastination. If you are leaving something to the last minute, there is actually far less time than that.

We need to find a balance between gloomy pessimism and Pollyanna optimism. Jeffrey Vancouver, a psychologist at Ohio University who specializes in the study of motivation, has succeeded in locating optimism’s sweet spot. He found that, in a sense, we are motivational misers who constantly fine-tune our effort levels so that we strive just enough for success and use the prospect of failure as an indicator that we should up our game.

7a

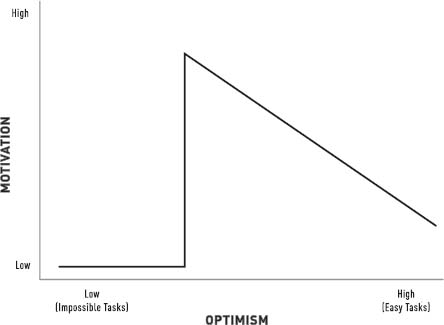

Look at the figure on the next page.

5

The vertical axis is motivation and the horizontal axis is optimism (that is, how difficult we perceive the task to be). Sensibly, we want the greatest reward for the least effort. Along the horizontal axis moving right, we start off with impossible tasks, too difficult to pursue. Why concentrate our resources where we will reap no reward? As tasks become easier and our optimism increases, we reach a tipping point. Motivation suddenly peaks: we believe that a win is possible, even though it will require considerable effort. As our optimism rises even further, our motivation falls, this time slowly. Eventually, we end up at the far right of the figure with tasks we believe we can easily perform. We're not motivated to accomplish these tasks because we deem them literally effortless. Most procrastinators are on the left of this chart, underestimating their ability, but a few are on the far right, believing that they are better than they really are.

6

Since most procrastinators tend to be less confident than non-procrastinators, we will start off by focusing on how to increase optimism, as it plays a central role in expectancy. Then we will consider overly confident procrastinators and learn how to gently deflate their overblown expectations.

REALISTIC OPTIMISM

A little optimism helps us persist when it comes to tackling difficult tasks. “Next time,” you might optimistically think, “it will happen for me.” Such a belief will keep you going much longer than a more realistic “Success is going to take about two or three dozen more tries.” But it isn’t obvious how to achieve this sunny disposition. Slogans and aphorisms such as “Be positive!” tend to be as ineffective as they are popular; they work best for people who are already optimistic and can actually make matters worse for people who aren’t.

7

But don’t despair. After more than fifty years of research into developing effective options for improving optimism, researchers have identified three major proven techniques: Success Spirals, Vicarious Victory, and Wish Fulfillment.

SUCCESS SPIRALS

Whatever sport you are passionate about, from football to table tennis, your favorite athletic icon likely embodies the principle of success spirals. I am a fan of mixed martial arts, which I first started watching in the mid-1990s when I took up tae kwon do with a friend. Although I quickly sustained a knee injury, which stopped my martial arts practice in its tracks, I kept watching. I became fascinated by Royce Gracie and Matt Hughes, seemingly unbeatable fighters who once dominated the sport with their respective contributions of Brazilian jujitsu or wrestling skills and conditioning. Each victory, though, was a lesson to their competitors; eventually, these champions' abilities were countered or copied, and they fell. A titleholder of five years ago would likely be hard pressed to remain a contender today. One of the few champions who managed to endure is Georges St. Pierre. Remarkably, he attributes his present success to an old failure—he was knocked out by Matt Sera. As St. Pierre puts it, “I think that loss was the best thing that ever happened to me, and skill-wise I'm way better than I used to be before.” In a rematch between the two the following year, the referee stopped the fight when Sera was unable to defend himself from St. Pierre’s attacks.

What makes Georges St. Pierre such a resilient combatant is his history of overcoming adversity, which includes a hardscrabble Montreal childhood. His persistence enabled him to transform initial failure into success, which in turn gave him the confidence to continue fighting and to improve in the future.

8

This is an example of a success spiral: if we set ourselves an ongoing series of challenging but ultimately achievable goals, we maximize our motivation and make the achievement meaningful, reflecting our capabilities. Each hard-won victory gives a new sense of self and a desire to strive for more. It is similar to the way Polynesian explorers colonized the South Pacific. From their home port they saw in the distance signs of a new island—a new goal—reachable if they made the proper provisions. Setting sail, they eventually made land, only to see another distant island from their new vantage point.

9

Every step forward is enabled by the step just taken.

For those who suffer from chronic discouragement and expect only failure, success spirals offer a way out. Initiating them is the trick, as everyday living doesn’t easily provide a structured and confidence-building series of accomplishments. However, great opportunities are available: wilderness classes and adventure education. Much like tribe members in a season of

Survivor,

participants from management trainees to juvenile delinquents go on outings where they are challenged to overcome extremely difficult tasks with the help of inspirational guides. Outward Bound is the longest-running and most popular of these wilderness programs. In small groups, participants complete demanding expeditions on land or sea that can involve rafting, sailing, rock climbing, caving, orienteering, or horseback riding. Problem solving and personal responsibility are built in; individuals have to make key decisions, both before (what to pack?) and during (which way and how?). As a hundred studies have concluded, these wilderness programs improve self-concept, particularly self-confidence.

10

One of the keys to the power of such programs is that participants leave with a vivid success experience they can hold on to—there’s nothing vague about crossing a river or climbing a mountain or figuring out how to deal with the unexpected. Personal stories of triumph can bolster people’s spirits for years to come. “I did it!” translates into “I can do it.” In follow-up assessments, wilderness program participants report that their self-confidence kept growing; having accomplished in the wild tasks they thought they couldn’t possibly do, they set higher goals for themselves at home. This is the essence of a success spiral: accomplishment creates confidence, which creates effort resulting in more accomplishment.

Parents can start these success spirals in their children. Structured extracurricular activities that provide a circle of encouragement and a venue for achievement can increase a child’s academic achievement and self-esteem as well as reduce drug use, delinquency, and dropping out.

11

In particular, scouting provides an almost textbook recipe for creating tangible challenges that promote feelings of confidence.

12

With the motto “learning by doing,” the Scouts reward a progressive series of tasks with proficiency badges that recognize each accomplishment, culminating in the coveted super-scout Baden-Powell Award.

13

Building a fire, setting up a tent, camping out, and cooking a meal for the group are all accomplishments kids can tell their parents about and—more importantly—remember themselves. Such success stories gradually build into a narrative that helps a child face the next challenge.

7b

Here is a personal example of a success spiral in action. A close friend of mine has a son with self-confidence and anxiety problems: since he doesn’t expect to succeed, he gives up quickly. So, his parents enrolled him in martial arts at a very strict tae kwon do dojo. It took the boy several attempts to get his yellow belt, but eventually he did. This turned out to be the pivotal experience that changed the course of his life, and it wasn’t because he became better at fighting. Every time he was tempted to give up in other areas of his life, especially school, his parents reminded him of how he had to persevere to get that yellow belt and how good it felt to receive it in the end. Having overcome obstacles in the past, he now routinely strives to overcome any new ones that arrive.

As adults, you might not have the time to try Outward Bound or share my passion for martial arts, and you are definitely too old for the Scouts. No worries; there are plenty of other options to create a success spiral. The secret is to start small and pay attention to incremental improvement, breaking down large and intimating tasks into manageable bits. Like the old adage about how to eat an elephant—one bite at a time—you carve difficult projects into a series of doable steps, purposefully planning in some early accomplishments. If you don’t feel up to writing a whole report, find a small portion you do feel capable of. Could you do the headings? Perhaps there are a few apt quotes to set aside? How about finding a few similar pieces to inspire you or to provide direction for organization? If you can’t run a mile, then run a block. Stop when you've done that and next time try two blocks. Keep note of your progress, and watch how quickly you get to a mile. Nobody has to know about your small successes; keep them as your own happy secret and let them encourage you. The trick is taking the time to acknowledge incremental change, perhaps by recording your performance in a daily log.

Remember, there is always a path toward progress, no matter how small the increments. The better you are able to recognize subtle advances toward your goal, the more likely your confidence will continue to grow.

14

Success breeds success.

To help you put this into practice, throughout this chapter and the next two, I've included sections called

Action Points.

These sections give you pointers about how to put what you have read directly into action, easily and without delay. Here is the first.