The Procrastination Equation (11 page)

Read The Procrastination Equation Online

Authors: Piers Steel

The online procrastination discussion boards often serve as confessionals of delay-induced torment. Here are half a dozen examples culled from two online forums,

Procrastinators Anony-mous

and

Procrastination Support:

•I've been very successful in many ways and managed to accomplish a lot in my life. But the process is miserable—I procrastinate, feel terribly guilty, get depressed, do work marathons, promise to change, and then start procrastinating again. I'm now at a point professionally where I've procrastinated so much on so many things that the work has really piled on and I'm fearful and unclear about how to dig myself out of the hole I'm in.

• The semester started two weeks ago and so far it has gone well. I was doing every assignment early and had so much free time but since then I have reverted to my old self. I fear for the worst and I have about two months until mid-term when my marks are due. I know I'm not as bad a student as shown in my report cards but I can’t seem to get my work schedule in gear.

• Whenever I told people I was a horrible procrastinator, they would usually laugh, and then say they were too. But they seemed fine; their lives weren’t on the brink of destruction because of their procrastination, like mine was. Can any of you please help me out?

• I really just want to DO WHAT I'M SUPPOSED TO WHEN I'M SUPPOSED TO DO IT! Whether I intrinsically want to or not, like NORMAL PEOPLE do. It hurts me so much that I cannot simply do that.

• And I'm so ashamed of even needing to resort to something like this. What kind of person am I that I have such a lack of self-control? I have fought and fought and fought over the years . . . I feel like it’s a dying battle.

• This habit isn’t funny, but I've always pretended it was. Really, though, it’s pretty tragic. It takes me months to respond to e-mails, costing me personally, socially, and financially . . . the only thing I really ever finish is dessert.

Unfortunately for these procrastinators, guilt and poor performance won’t be the entire story. When it comes to gratification, procrastinators stress immediacy. Like the spoiled rich girl Veruca Salt from Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, they don’t care how, they want it now. Immediate gratification often comes at the cost of larger, later rewards, so consequently, procrastination is like running up a charge on your emotional credit card. You don’t have to pay it now, but when the bill is finally due there will be compound interest. We fritter away the days with the small pleasures of television and computer games, of Internet surfing and Sudoku puzzles and end up with nothing to show for it. This is a recipe for regret.

In the short term, we regret what we do, but in the long term, we regret what we don’t get done. Inaction causes us the greater suffering. Not to have done, not to have tried, to have put it off—this is part of the human condition, so we all suffer from it to some degree. You almost certainly have or will have regrets in at least one of these three life areas: Success, Self-Development, and Intimacy.

31

Looking back on our lives, it is common to feel that we should have gone for that degree or tried harder in class, that we should have mustered up the courage and risked rejection for that date, or made time for that phone call to Mom. We are haunted by the ghosts of our own lost possible selves—what we might have been: could've, should've, but didn’t.

32

I am no exception to procrastination’s rule of regret. My brother Toby suffered from sarcoidosis, the same debilitating disorder that took the life of comedian Bernie Mac. When my family had to make the decision to take Toby off his ventilator and wait with him until he took his last breath, I was crushed with knowing what a fool I had been with my time. I regret putting off trips to see his plays. I regret not making it to the hospital sooner to see him. I regret the littlest things, like not taking more time to watch a bad movie on TV with him while eating take-out. He was the smartest, funniest person I have ever known and I took it all for granted. In keeping with life’s synchronicity, soon after my brother’s funeral I found a poem in the newspaper written by Mary Jean Iron. I clipped it to remind myself of my carelessness. It is still there, in my desk drawer, waiting for this moment:

Normal day, let me be aware of the treasure you are.

Let me learn from you, love you, bless you before you depart.

Let me not pass you by in quest of some rare and perfect tomorrow.

Let me hold you while I may, for it may not always be so.

One day I shall dig my nails into the earth, or bury my face in the pillow,

Or stretch myself taut or raise my hands to the sky

And want more than all the world, your return.

Put down this book and get going. Don’t hesitate: call your mother, start writing that essay, ask out that special person you have had your eye on. Now is the moment you have been waiting for.

LOOKING FORWARD

Have you really put this book down? I didn’t think so, but don’t worry. I know it is not that simple. Interventions are still coming—you will hit them when you reach chapter seven. Right now, I want to continue focusing on the price of procrastination. In the next chapter, we look at the economic cost of procrastination to society. When we calculate the final figure, it will probably be larger than even your most outlandish guess.

Chapter Six

The Economic Cost of Procrastination

HOW BUSINESSES AND NATIONS LOSE

Momentary passions and immediate interests have a more active and imperious control over human conduct than general or remote considerations of policy, utility or justice.

ALEXANDER HAMILTON

W

hen exploring procrastination, no other country provides as many good examples as the United States. Almost two-thirds of all procrastination research is done with American citizens, and no wonder, given what it costs them. Here’s how to calculate it. First, how many workers are there in a country? For the United States, the figure is over 130 million, but we will round down for ease of calculation. Second, what is the annual average wage for those workers? Estimates can reach over $50,000, but we will be conservative and go with the lower figure of $40,000. Finally, how many hours do people work each year? The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development provides that figure: Americans clock in 1,703 hours, or slightly more than 212 eight-hour workdays, each year.

1

Finally, we have to determine how many hours each day people procrastinate. Two companies, America Online and Salary.Com, partnered together to survey the work habits of more than ten thousand people; the result was over two hours of procrastination in every eight-hour day, not including lunch and scheduled breaks. Once again, we will round the estimate for ease of calculation, this time downward to an even two hours.

2

Keep in mind as we calculate the final figure that I've used conservative estimates at every step. We have 130 million people who spend about two hours out of every eight at work procrastinating, or 414 hours per year. Each hour is worth at least $23.49 (i.e., $40,000 divided by 1,703 hours), though if their employers are making a profit, they are worth more than that. At a minimum, then, procrastination is costing organizations about $9,724 per employee each year ($23.49 times 414).

3

Multiply that by the total number of employees in the United States, and you get $1,264,1200,000,000. In other words, a conservative estimate of the cost of procrastination for just one country in just one year is over a trillion dollars. This number may seem surprisingly large, but not if you are an economist. Gary Becker, who won the Nobel Prize for economics, concludes, “Indeed, in a modern economy, human capital [the work people do] is by far the most important form of capital in creating wealth and growth.”

4

With a quarter of each person’s work day spent dithering, procrastination is going to be costly.

Still, if this trillion-dollar figure makes you balk, fine. Revise any part of these calculations downward to what

you

think is reasonable. Cut the number of procrastination hours in half, pay everyone minimum wage, but pretty much anything times 130 million is still going to be a hefty sum. Myself, I think the true costs of procrastination are far more than a trillion dollars. Procrastination during the business day is only part of the picture.

5

Our ability to save money or make timely political decisions is also affected by procrastination, and the costs there should be over a trillion dollars too. And here is how it is happening.

TIME IS MONEY

The more we procrastinate at work, the more it costs us. Unfortunately, it’s not just entry level workers who procrastinate but their managers and CEOs as well. Consider the Young Presidents' Organization, a club of corporate heads under forty-five who run companies worth more than ten million in revenue. In a survey of 950 of its members, the most troublesome problem reported was “facing up to a task which was, for various reasons, personally distasteful.”

6

As my own research program shows, organizational teams, work groups, and task forces procrastinate.

7

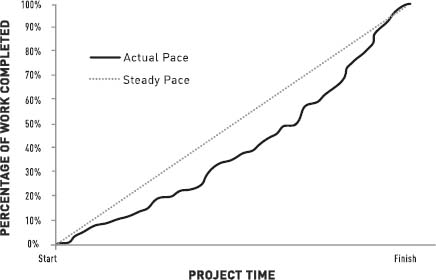

The graph on the next page charts the average work pace of business groups over the course of their projects (the solid line) along with a hypothetical steady work pace (the dashed line). In both form and content, it parallels the graph from chapter 2 that featured student procrastination. As can be seen, both students and business groups demonstrate the same shape of curve, whereby people start off slow and then pick up the pace.

6a

ORGANIZATIONAL TEAM PROCRASTINATION

How has procrastination wormed its way into every inch of the business world? For the most part, by way of the same device that tempts students from their studies—the Internet. Dubbed e-breaking or cyberslacking, surfing the Net is the most serious of employees' time-wasting activities.

8

About one in four people admit to playing online games on the job. In fact, gaming websites report a sharp drop in traffic at exactly 5:00 p.m., the end of most people’s work day.

9

Similarly, “video snacking,” when people surf for and trade clips of all types, is a huge distraction. Though video use tends to spike during the lunch hour, it is prevalent at all times, and is expected to soon account for half of all Internet traffic.

10

As summarized by Miguel Monteverde, executive director of AOL Video, “Based on the traffic I'm seeing, our nation’s productivity is in question.”

11

Interestingly enough, this trend extends to pornographic sites as well, which get 70 percent of their traffic from the nine-to-five crowd.

12

Finally, of course, there is social networking. The company Talkswitch provides a perfect example; it recognized it had a problem when it discovered that all sixty-five of its employees were using Facebook—simultaneously.

13

To cope with this tsunami of procrastination, most companies ban inappropriate Internet use, but it is difficult to enforce. Employees rearrange their computer screens so they can’t be easily seen from the doorway, giving them time to hit a “Boss Key” that quickly opens a legitimate application. There are also several applications that mask illicit activities, such as one that allows Internet browsing within a Microsoft Word shell, making it difficult to detect dillydallying ways. Especially notable is the website “Can’t You See I'm Busy,” which makes it hard to detect games hidden within graphs and charts. In response, two-thirds of companies firewall their servers, fettering people’s Internet access to various degrees. WebSense, which ironically makes software that filters the Internet, automatically monitors employees' Internet use and cuts off their access when they reach two hours of personal surfing. Other organizations enforce wide-ranging, perpetual restrictions on gambling, pornography, video sharing, and social networking sites alike.

14

Banishing people from games and Internet sites does not eliminate polymorphic procrastination because it can manifest itself in so many ways. Solitaire is pre-loaded on most Windows platforms, making it the top computer game of all time, even favored by former president George W. Bush.

15

Memory keys often have games embedded on their chips, as do personal digital assistants (PDAs), which provide unrestricted Internet access. You can also go old school and avoid the computer completely. The ritual start of many a working day involves the diversion of the news. When I visit my sister, we scramble to be the first to get to the Sudoku in the morning paper. In the White House, Bill Clinton completed the

New York Times

crossword puzzle daily.

Procrastination isn’t fuelled by games alone. As Robert Benchley quipped, “Anyone can do any amount of work providing it isn’t the work he is supposed to be doing at that moment.” We procrastinate on important tasks by doing the unimportant. For many of us, this means e-mail, which now takes up 40 percent of work life.

16

With every notifying “ding,” workers instantly redirect their attention to reading the latest in an endless stream of electronic missives. Only a small seam of this e-mail bonanza is useful; the rest is junk. Though this deluge of electronic debris is partly composed of spam—unsolicited bulk e-mail—our greatest threat is the enemy behind the lines. Coined

friendly spam,

much of the junk we receive is created by our friends and co-workers who carelessly mass e-mail us about every social event, virus hoax, urban myth, trivia tidbit, or arcane corporate policy change. Since all these e-mails have the potential to be useful, they must be read to conclude they aren’t. And then there are e-mail’s peripheral effects. In a study of Microsoft workers, people took an average of fifteen minutes to re-focus on their core tasks after answering an e-mail interruption.

17

Combine this with the finding that information workers check their e-mail accounts over fifty times a day, over and above the seventy-seven times they text message, and theoretically no work should ever get done.

18

More realistically, the business research firm Basex puts the interruption and recovery time at a little over a quarter of the work day (about two hours),

19

which is consistent with studies on multi-tasking that conclude that switching attention is extremely detrimental to performance.

20

In short, despite the veneer of activity that e-mail checking provides, there is not much light for all that heat.

SAVING FOR LATER YEARS TOO LATE

Procrastination doesn’t just diminish our wealth by decreasing our productive hours. It also reduces the benefit we gain from our productivity itself. Our wealth is determined not only by the money we make but also by the money we save. Saving is a tried-and-true path to riches, as every dollar you put aside starts to reap the miracle of compound interest. Furthermore, since the dollars you save are invested, savings can help the nation as a whole, spurring economic expansion. When adopted, a policy of savings can be hugely successful. Since 2004, average Singaporeans, for example, have been wealthier than the average American largely because they save more.

21

Unfortunately, when procrastination overtakes a society, saving becomes the exception and borrowing becomes the rule, a trend that can easily lead to financial ruin. Just consider your retirement savings account.

Aside from your plans to win the lottery, retirement rests on a three-legged stool. The first leg is the government, which, due to a bad habit of spending more than it receives, won’t always be able to deliver on what little it promises. In the United States by the year 2040, for example, people can hope to receive only about two-thirds of their scheduled Social Security benefits, and on the heels of the 2008 global financial crisis, this percentage will probably decrease.

22

The second leg is represented by businesses, which can put money aside for you as a form of compensation, typically in the form of a Defined Contribution plan.

6b

In such a plan, you decide how much, or rather how little, of your paycheck to contribute, and most allocations are matched by the company. The third leg is you, your decision to initiate and open independent retirement accounts. This is the most dependable option—except, of course, that it still depends on you.

By becoming a society of procrastinators, we have caused the retirement stool to be increasingly wobbly, as most people are socking away less.

23

People are neither starting their own retirement accounts nor contributing to company plans, despite the fact that allocation matching is the equivalent of getting free money. When they leave work, their financial backsides rest on a stool supported by a single stubby peg derived from the government’s forced savings program. Again, procrastination proves to be particularly poignant in the United States. In 2005, after decades of decline from originally double-digit rates, American household savings finally went into the negative. In other words, instead of saving today’s money for the future, people were going into greater debt by spending tomorrow’s money today—on average about half a percent more than they earned. To do this, not only did they borrow against their homes, in the form of mortgages, but about one in five borrowed against funds they had already set aside for retirement, putting themselves further behind.

24

Worst of all, some of this financing was arranged through “liar loans,” which initially seem affordable but eventually create financial ruin. Variable mortgages entice homeowners to buy well beyond their means, while “pay day” advances provide the desperate with temporary respite but leave them much worse off. They end up repaying each loan many times over; the interest rates of “check cashing” shops often exceed 500 percent a year.

25

These are financial products that procrastinators are prone to fall for, products with short-term benefits but exceedingly high long-term costs.

The experts share the consensus that this situation is not ideal. At least something should be put aside for retirement; ideally, you should be saving 10 to 20 percent of your salary or higher if you are already in your forties.

26

Even before the 2008 global financial crisis, which alone lowered pension accounts by at least a fifth, an increasing number of Americans believed they were not putting enough aside for their old age.

27

And they are right. When retirement comes, more than four out of five Americans will find they haven’t saved enough for their needs and by then it will be far too late to do anything about it.

28