The Procrastination Equation (9 page)

Read The Procrastination Equation Online

Authors: Piers Steel

Are we right, Huxley, Postman, Offer, and I? Well, look around you. Exactly how many recreational or entertainment pursuits do you have readily available? A typical household can hold hundreds, from widescreen TVs to Internet portals. Never before in our history have there been as many temptations, as succulently devised, as readily available, and as adeptly marketed. Adam and Eve only had to deal with a juicy apple purveyed by a serpent. Nowadays, our apple is caramel coated and chocolate dipped, marketed with a multi-million dollar advertising campaign in a blitz of commercials, pop-ups, and inserts.

32

Inevitably, as our lives drown in these diversions, our procrastination is on the rise.

LOOKING FORWARD

There is no turning our backs on modern life. The free market, in one form or another, will continue and the pace of invention will only accelerate. We will benefit from many of these innovations, but not all. The exploitation of the limbic system is baked into capitalism and you can’t stop it without making the entire wonderful wealth-generating machinery grind to a halt. Someone will always create a product that provides short-term pleasure along with considerable but deferred pain simply because we will buy it. Consequently, dealing with constant temptation and its potential for creating procrastination is and will continue to be part of living in this world. Good thing you are reading this book, then. Learning better ways to cope with temptation and procrastination is what we will be doing together in later chapters; we will make the Procrastination Equation work for us, one variable at a time. But first, let’s whet your appetite by acknowledging what procrastination costs you and society at large. A single incident of procrastination can be petty, but once you see the ultimate toll, I think you will find that it is an opponent worth fighting. I surveyed four thousand people to find out where they procrastinated most. The next chapter reveals what they told me and the personal price they paid for putting things off.

Chapter Five

The Personal Price of Procrastination

WHAT WE MISS, WHAT WE LOSE, AND WHAT WE SUFFER

We have left undone those things which we ought to have done; and we have done those things which we ought not to have done.

THE BOOK OF COMMON PRAYER

F

or enduring fame and sheer depth of procrastination, Samuel Taylor Coleridge stands alone. One of the great poets of the nineteenth-century romantic era, Coleridge might have been its greatest, but that title is more often given to his one-time and more diligent friend, William Wordsworth. Coleridge’s tragic weakness was procrastination. He put off his work and his obligations, at times for decades. The poems for which he is best remembered, and which are still regularly studied in English literature classes, all show traces of procrastination.

Kubla Khan

and

Christabel

were both eventually published as fragments—unfinished works—nearly twenty years after he began them, and

The Rime of the Ancient Mariner,

though completed, was five years late to press.

Everyone—his family, friends and even he himself—recognized Coleridge’s procrastination. His nephew and editor, Henry, wrote that his uncle was “the victim of a procrastinating habit,” and Coleridge himself describes his procrastination as “a deep and wide disease in my moral Nature . . . Love of Liberty, Pleasure of Spontaneity, these all express, not explain, the fact.” However, it was his close friend Thomas de Quincey who provided the best account, having shared with Coleridge not only a proclivity to procrastinate but also a severe drug addiction—Quincey’s autobiography is aptly titled

Confessions of an English Opium-Eater.

As Quincey wrote:

I now gathered that procrastination in excess was, or had become, a marked feature in Coleridge’s daily life. Nobody who knew him ever thought of depending on any appointment he might make. Spite of his uniformly honourable intentions, nobody attached any weight to his assurances

in re future

[in regard to the future]. Those who asked him to dinner, or any other party, as a matter of course sent a carriage for him, and went personally or by proxy to fetch him; and as to letters, unless the address was in some female hand that commanded his affectionate esteem, he tossed them all into one general

dead-letter bureau,

and rarely, I believe, opened them at all.

Coleridge’s excuses for lateness have themselves become legendary. His correspondences consist frequently of apologies, at times even an extended run of them; witness his letters to a Mr. Cottle, a publisher who bought the copyright to a book of his poems—sadly, in advance. Deserving special mention is the “Person from Porlock,” who Coleridge claimed irrevocably interrupted his recollection of the opium-induced dream that served as the basis of his poem

Kubla Khan.

The poem runs only 54 lines, instead of the intended 200 to 300. As judged by Robert Pinsky, an American poet of our time, the “Person from Porlock” is the most famous of fibs from a long line of writers who are “better at making excuses or self-indictments than at getting things written.”

But what did this procrastination reap for Coleridge? As Molly Lefebure describes his situation in her book

A Bondage of Opium,

“his existence became a never-ending squalor of procrastination, excuses, lies, debts, degradation, failure.” Financial problems pervaded his life, and most of his projects, despite elaborate planning, were barely begun or finished. His health was terrible, exacerbated by his opium addiction, for which he delayed medical treatment for an entire decade. His enjoyment of work dissolved in the stress of unmet deadlines—“My happiest moments for composition are broken in upon by the reflection that I must make haste.” He lost rare friends, such as Wordsworth, and his marriage ended in separation because of it.

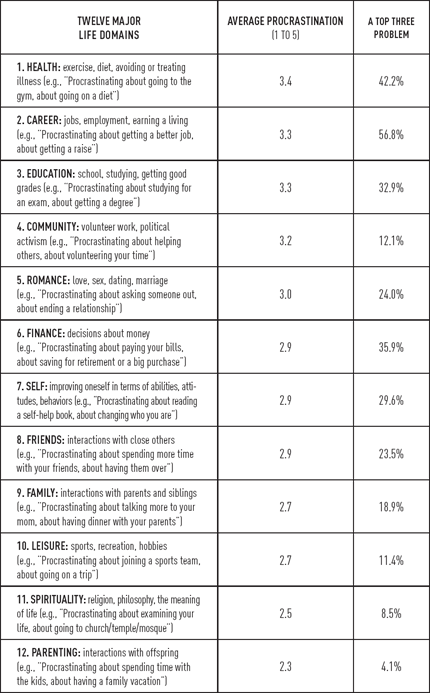

Coleridge’s woes clearly illustrate that procrastination is capable of damaging all aspects of our lives. However, only the most confirmed of procrastinators will experience anything that approaches Coleridge’s sad life. Most of us procrastinate significantly in only a few of life’s domains. To find out about the procrastination habits of ordinary people living in our own time, I put up a survey on my website and four thousand people answered it. I asked them to tell me how much they procrastinated in each of twelve major life domains and to rank what was most problematic for them.

1

The table on the next page reflects the results. The first column is the domain, and the second column records people’s average level of procrastination, with a score of 2 indicating

seldom,

3 indicating

sometimes,

and 4 indicating

often.

The third column indicates the percentage of people who chose that life domain as a “top three problem.”

As you look at this table, pay attention to the domains where the numbers in the last two columns are both high: these are the trouble spots.

Procrastination causes us grief at school, at work, and in our private lives, particularly in relation to health. Eighty-nine percent of people believe they have major problems in

at least

one of these three life domains alone, with 9 percent approaching Coleridge’s levels by reporting all three. There is also a pattern to people’s procrastination; most of these life domains cluster or hang together in groups. For example, many of the people who reported procrastinating about their financial situation also reported putting off education and other activities that might improve their careers (domains 2, 3, and 6). If you are suffering in one of these three areas, you're likely to feel that the other two are also problematic. This “Success” cluster of concerns is overall the most prevalent in terms of procrastination.

A second cluster focuses on “Self-Development,” as people who put off their health issues (domain 1) also tend to put off spiritual quests, leisure activities, and self-improvement programs (domains 7, 10, and 11). This is the broadest cluster, as it is also connected to your social life, being part of your community, or pursuing a romance (domains 4 and 5). A final cluster could be labeled “Intimacy” by virtue of grouping together close friends, family, and parenting (domains 8, 9, and 12). This is the least problematic of the lot, especially in regard to parenting. Happily, very few respondents report putting off raising their kids—there is an immediacy to caring for children that trumps everything else.

Whether your procrastination lies in the Success, Self-Development, or Intimacy cluster determines the price you pay for procrastination, as these three areas translate into three major costs: your Wealth, Health, and Happiness. Naturally, those who put off the Success cluster and its career or financial aspects will be less wealthy. Those who procrastinate on Self-Development will experience poorer health, both of body and spirit. And though happiness is affected by the previous two clusters, Success and Self-Development, it has the strongest ties to Intimacy. In a different meta-analysis that I conducted, based on close to twelve hundred studies, I established that the biggest predictors of happiness are traits leading to fulfilling interpersonal relationships; great wealth and good health mean less without someone to share them with.

2

Wherever your procrastination lies, the more you do it, the greater the cost. Just take a look.

FINANCIAL PROCRASTINATION

The most common excuse I hear from people who procrastinate at work is that they are more creative under pressure. I can see how it might appear this way. If all your work occurs just before a deadline, that is when all your insights will happen. Unfortunately, these insights will be relatively feeble and few compared to the insights of those who got an earlier start, since under tight timelines and high pressure people’s creativity universally crumbles.

3

The bleary-eyed 3:00 a.m. crowd scrambling to finish a project will usually come up with routine, unremarkable solutions. Innovative ideas are typically built on the bedrock of preparation, which includes a laborious mastery of your topic area followed by a lengthy incubation period.

Other procrastinators try to justify their delays by indicating that they work most efficiently closer to the deadline. This time, they are partly right. You do have more motivation just before the clock strikes twelve and you cross the deadline. But what the procrastinator is creatively arguing here is not whether we work hardest at the eleventh hour (which we do) but that working

earlier

actually harms our performance. In other words, this procrastinator says that working today

and

tomorrow is worse than working only tomorrow—a clumsy lie.

No matter what index of success we examine, procrastinators tend to perform worse than non-procrastinators. There is some variation based on whether we look at education, career, or income, but not in a way you are going to like: as procrastination moves from school to job to measures of overall wealth, the worse its effects. The results (which I summarize in my article “The Nature of Procrastination”) look like this.

4

For high school and college students, only about 40 percent of procrastinators have above-average grades, while 60 percent are below. If you are one of the lucky 40 percent, you should recognize that though procrastination is a handicap, you are probably compensating for it with other attributes, like a brilliant mind. Don’t fall into the trap of thinking that this vice is actually helping you out. Not that I should judge . . . I put off studying for too many finals and tried to erase my late start by doing a series of all-nighters, a strategy that ended with me dozing peacefully through the last half of a French exam. The consequence of that impromptu nap has me dreading foreign languages to this day. The funny thing is that almost everyone else has a similar story to share.

Students spend roughly a third of their waking hours on diversions they themselves describe as procrastination.

5

On average, students engage in over eight hours of leisure activities on the two days prior to exams,

6

and their inability to effectively manage their time is a self-reported top concern as well as a reason for dropping a course.

7

Worse, this trend doesn’t abate when the stakes get raised. It is a major reason why most potential PhDs leave school before graduation, and the three little letters they get after their name are ABD (all but dissertation).

8

ABDs are so common that cartoonist Jorge Cham, for example, makes a living by writing

PhD Comics,

a strip dedicated to chronicling PhD students' procrastination. Incredibly, after graduate students have gotten into a competitive academic program, done all their course work, perhaps even gathered their dissertation data, and need only to write it up and defend their thesis, at least half never complete the process despite the immense investment of time and the significant rewards for completion (on average, a 30 percent increase in salary).

9

Procrastination is the primary culprit.

Moving on to the field of career success, we find that the impact of procrastination intensifies a little bit. As judged by their peers, 63 percent of procrastinators are in the below-average, unsuccessful group. From the get-go, procrastinators have trouble getting going, and they put off the job hunt. When unemployed, they stay that way for longer.

10

Once employed, most will find that work life is less forgiving than college or high school. The stakes are higher, so it is harder to get your boss or your clients to give extensions. For example, Michael Mocniak, general counsel at Calgon Carbon, got fired from his job for putting off processing his invoices—$1.4 million worth.

11

Furthermore, on-the-job projects can be larger and much harder to complete at the last minute; work is less predictable, so you could find the final hours before a deadline suddenly double-booked. Still, there is that 37 percent of procrastinators whose wealth is at least above average despite their character flaw. If over the breakfast table you call the CEO mom and the Chairman of the Board dad, you are likely going to be wealthy no matter what your personal vices are. Other chronic procrastinators might end up in a career—and there are a few—where it is very difficult to procrastinate—careers with built-in daily goals, like sales or journalism. With everything due today, the leeway to procrastinate is exceedingly slim.

Finally, when we talk about overall financial success, the procrastination numbers again step up. By their own admission, only 29 percent of procrastinators consider themselves successful, with the remainder describing themselves as below average. The reasons for this are legion: procrastination’s harmful touch extends into dozens of nooks and crannies that affect your bank balance.

12

For example, the U.S. government gets at least an extra $500 million each year thanks to tax procrastination. A typical procrastinator’s mistake is failing to sign the forms in the last-minute rush, making them invalid and subject to a late penalty.

13

But procrastination hits our savings and spending in many other ways.

Savings speak to what Albert Einstein called the eighth wonder of the world—compound interest. The money you save not only earns interest, but the interest earns interest, like your children having grandchildren. Such is its power that if you put aside $5,000 each year between the ages of 20 and 30, you would retire richer than if you started putting that five grand aside

every

year from the age of 30 on. Alternatively, consider the native Indians who sold Manhattan Island for about $16 worth of beads. Had they taken the money and invested it, with compound interest they could pretty much have bought back the entire island today and everything on it—from the Christmas trimmings at Rockefeller Center to the boardroom leather chairs at Trump Tower.

14

Too bad procrastinators rarely act on their intention to sock money away for retirement or even a rainy day. If they were characters in one of Aesop’s cautionary tales, they'd play the grasshopper instead of the ant. All that compound interest, all those potential investment dividends, lost and almost impossible to regain. As a paper in

The Financial Services Review

concludes, “We find the levels of contributions required for individuals who start saving late are so high it is questionable whether they are affordable for anyone not on a high income.”

15