The Procrastination Equation (4 page)

Read The Procrastination Equation Online

Authors: Piers Steel

Let’s create an intention. Two weeks from now, you will have a choice between staying up late and honing a budget proposal for work, due the next day, or meeting your friends for drinks at the bar. At the moment, you value polishing your proposal far more than seeing your friends, as the former could lead to a sizable pay raise while the latter will only be a fun get-together. You wisely intend to work on the proposal that night, but will you stand fast? Flash forward two weeks to the very night the choice must be enacted, and life suddenly switches from the abstract to the concrete. It isn’t just friends, it is Eddie, Valerie, and Tom. These are your best friends; they are texting you to come down to the bar; Eddie is so funny; Tom owes you a drink and you owe Valerie a drink; and maybe you can bounce some ideas off them. Besides, you deserve a break because you've worked so hard. So you give in, and once you are there, you forget about going back to work. Instead, you pledge to get up early tomorrow morning because “your mind will be fresher then.” The culprit for your intention-action gap is time. When you headed down to the bar, it probably took you just 15 minutes to get there, a minuscule delay compared to the deadline for tomorrow’s task, which is orders of magnitude off into the future—specifically 96 times greater (i.e., 24 hours divided by 15 minutes). As per the Procrastination Equation, that difference causes an almost hundredfold increase in the relative effects of delay. Indeed, there’s no time like the present, and it’s no wonder your intentions fell through.

THE PROCRASTINATION EQUATION IN ACTION

To see all the pieces of the Procrastination Equation in action at once, it would be tempting to try swapping in your own scores on impulsiveness, expectancy, and value and checking out the results. Unfortunately, it isn’t that easy. To accurately apply the equation to a specific individual we would need a controlled laboratory experiment. In the lab we can put everything into an exact and measurable metric by artificially simplifying your choices, having you push a bar, or run a maze to receive a food pellet, for example.

To demonstrate how the Procrastination Equation operates in a realistic setting, a better way is to apply it to the prototypical procrastinator. And nobody—nobody at all—procrastinates like college students, who spend, on average, a third of their days putting work off. Procrastination is by far students' top problem, with over 70 percent reporting that it causes frequent disruption and fewer than 4 percent indicating that it is rarely a problem.

14

Part of the reason that colleges are filled with procrastinators is that their inhabitants are young and therefore more impulsive. However, the campus environment must shoulder most of the blame. Colleges have created a perfect storm of delay by merging two separate systems that contribute to procrastination, each devastating in its own right.

The first system is the essay. The more unpleasant you make a task—the lower its value—the less likely people will be to pursue it. Unfortunately, writing causes dread, even revulsion for almost everyone. But welcome to the club. Writing is hard. George Orwell, author of the classics

Nineteen Eighty-Four

and

Animal Farm,

had this to say: “Writing a book is a horrible, exhausting struggle, like a long bout of some painful illness. One would never undertake such a thing if one was not driven by some demon that one can neither resist nor understand.” Gene Fowler, who wrote about twenty books or screenplays, was equally despairing: “Writing is easy, all you do is sit staring at a blank sheet of paper until the drops of blood form on your forehead.” To write this very book, I have been leaning on William Zinsser’s

On Writing Well: The Classic Guide to Writing Nonfiction.

Sure enough, on page 87, Zinsser confesses, “I don’t like to write.”

Added to the cruelty of assigned writing is the capriciousness of grading—low expectancy. Any essay that is re-marked by another professor may shift remarkably in grade—a B+ could become an A+ if you are lucky, or a C+ if you are not.

15

This is not because the marker is sloppy; it is because measuring performance is inherently hard. Just look at the variation in judges' scores at Olympic events or among reviewers critiquing films. From the students' perspective, such discrepancies mean there is no guarantee that their hard work will be recognized. Quite possibly, it won’t be.

The final aspect of the essay system that contributes to student procrastination is the distant due date—high delay. There are often no intermediary steps—you just hand the paper in when you are finished. At first the due date seems months and months away, but that is just the start of a slippery slope. You blink and it has become weeks and weeks, then days and days, and then hours and hours, until suddenly you are considering Plan B. Approximately 70 percent of all reasons given for missing a deadline or bombing an exam are excuses, because the real reason—procrastination—is unacceptable.

2e

As students themselves report, their top strategy is to pore over the instructions with a lawyer’s eye for any detail that could possibly be misinterpreted, later claiming, “I didn’t understand the instructions.”

16

There it is; university essays hit each key variable of the equation. Essays are grueling (low value), their results are very uncertain (low expectancy), and they have a single distant deadline (high delay). And if essays are hard in and of themselves, there are few harder places to do them than a college dorm. This leads us to the second system in that perfect storm: the place where this essay is supposed to be written.

College dorms are infernos of procrastination because the enticements—the alternatives to studying—are white hot. Superior in every aspect to essay writing, these pleasures are reliable, immediate, and intense. Consider campus clubs alone. At the university where I earned my PhD, there are about a thousand of them, catering to every recreational, political, athletic, or spiritual need, ranging from Knitting for Peace to the Infectious Disease Interest Group. These clubs will give you a new set of friends, with whom you will want to socialize—likely in one of the dozens of coffee shops and pubs a short walk from any place on campus. They'll also entice you to go to one of a dozen events occurring every week, from poetry readings to tailgate parties. With all the camaraderie, alcohol, sex, and—headiest of all temptations—the freedom to enjoy them all, university can lure us into the unregulated state of bliss where the liberties of adulthood are combined with only a minority of the responsibilities. From the moment students step into the classroom, inevitable conflicts are set in motion. Even Tenzin Gyatso, better known as the 14th Dalai Lama, reported of his student days, “Only in the face of a difficult challenge or an urgent deadline would I study and work without laziness.”

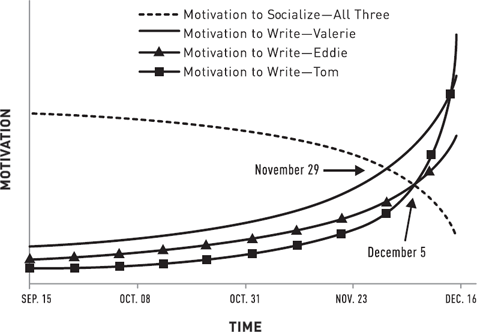

We can graph this dilemma using Eddie, Valerie, and Tom when they were back in their university days. They hang together, as they have a lot in common and all of them like to socialize rather than work. Still, there are differences among them. Valerie knows she isn’t especially bright but she has two cardinal virtues—she is levelheaded and responsible. Though she isn’t competitive, she sees the future pretty clearly, and can imagine one day graduating from college and getting her dream job. Tom is more ambitious and more confident of his abilities than either of his classmates but he is also the most impulsive. His cockiness and spontaneity arouse mixed feelings of envy and hate in many people who know him. Eddie, on the other hand, lacks desire as well as self-confidence. He was pressured by his family to go to college and he is unsure whether he can survive much less thrive academically. In fact, he doesn’t really care. At least he is comfortable being a slacker.

One mid-September morning, Eddie, Valerie, and Tom walk into my Introduction to Motivation class, where they find that a final essay is due three months later, on December 15. The graph on the facing page charts their likely levels of motivation and when each of them will start working. Their common motivation to socialize, represented by the dotted line, starts off strong in the semester and tapers off toward the end, partly in response to a lack of opportunity and ever-increasing guilt. Valerie, being the least impulsive, is the first to start working, on November 29 (the smooth, unadorned graph line). It takes another week before Eddie or Tom bears down—a significant gap.

In terms of the Procrastination Equation, although Tom is more confident (high expectancy) and competitive (high value) than Eddie, his impulsiveness means that most of his motivation is reserved until the end (the graph line with squares). Valerie’s motivation flows more steadily, like water from a tap, while Tom’s gushes like a fire hose when eventually turned on. Even though Tom starts working the same day as Eddie the slacker (the graph line with triangles), Tom’s motivation in the final moments should enable him to outstrip the others' best efforts.

MY OWN RESEARCH

Although Eddie, Valerie, and Tom are fictional, they are composite characters based on the thousands of students I have taught. As I stressed, there is no better venue for finding procrastinators than universities. Harnessing all this wasted motivation for science is the trick. It was great luck that as a graduate student I worked with Dr. Thomas Brothen. Thomas taught an introductory psychology course at the University of Minnesota’s General College, an institution designed specifically to increase the diversity of the university. Significantly, the class was administered through a Computerized Personalized System of Instruction, a nifty arrangement that allows students to pro-gress through a course at their own pace but is well known for creating high levels of procrastination. In fact, procrastination is such a problem that students are repeatedly warned throughout the course about the dangers of delay. And here is the beautiful part. Its being computerized meant that every stitch of work that the students completed for the course had a time-date stamp exact to the second. You truly can’t find a superior setting for studying procrastination.

Before the General College was closed, Thomas and I managed to follow and assess a few hundred students with his wired classroom. We even got around to publishing some of the results. Here are the basics of what we found. Observed procrastination and confessions of procrastination were closely linked, confirming that we were using the right venue. Also, procrastinators tended to be the lowest performers in the course and were more likely to drop out, confirming that they were worse off for putting off. Now these problems didn’t occur because procrastinators are intrinsically lazy; they were making the same intentions to work as everybody else. They just had trouble following through with their intentions at the beginning of the course. Toward the end, a different story emerged. Procrastinators actually started logging more hours than they had intended, with one student completing 75 percent of the course in the final week alone. They also weren’t procrastinating because of anxiety. The real reasons for inaction were the following: impulsiveness, hating the work, proximity to temptation, and failing to plan. And most significantly, each of these findings directly follows from the Procrastination Equation.

The ability of the Procrastination Equation to formulate these and other results forms the backbone of this book. I have already talked in depth about the connection between the intention-action gap and impulsiveness. Similarly, putting off work because it is unpleasant simply illustrates the effect of value on procrastination. Proximity to temptation highlights the effect of time. Students who said that if they chose not to study “they could immediately be doing more enjoyable activities” or that in their study location there were “a lot of opportunities to socialize, to play, or to watch TV” procrastinated more, a lot more. Remember that Eddie, Valerie, and Tom needed their motivation to write to exceed their motivation to socialize before they could get down to work. But the more readily available temptations become, the stronger they become and the longer they will dominate choices, necessarily creating procrastination. The findings from our study, such as procrastinators' failure to properly plan or to create efficient study schedules, also pointed to ways of combating procrastination. Proper planning allows you to transform distant deadlines into daily ones, letting your impulsiveness work for instead of against you. We will talk more about how to plan properly and the rest of these issues as you go through the book. But one last thing about this study.

There is an epiphany I want to share that occurred to me when I graphed the work pace of the class. Would their work pace replicate the curve that the Procrastination Equation predicted, starting off slow and then spiking toward the end like a shark’s fin? Would it follow the pattern that Eddie, Valerie, and Tom’s experience suggested? I couldn’t expect an exact match, as the equation couldn’t take into account weekends or the midterm-break lull, but I was hoping for something close. My findings are what you see on the next page. The dotted line is a hypothetical steady work pace, the dark line is what we observed, and the gray line is what the Procrastination Equation predicts. Notice which lines match together almost perfectly.

17