The Procrastination Equation (7 page)

Read The Procrastination Equation Online

Authors: Piers Steel

By 440

B.C.

, procrastination was spilling over from farming into fighting. Thucydides, the father of scientific history, wrote about it in the

History of the Peloponnesian War,

which chronicled the conflict between Athens and Sparta. This account, still studied in military colleges, discusses various aspects of personalities and strategies. Thucydides clearly considered procrastination to be the most wicked of character traits, useful only to delay the commencement of a war so as to lay a better groundwork for winning it. Another notable Greek reference to this trait is found in the work of the philosopher Aristotle, who wrote much of his

Nicomachean Ethics

on the weakness of the will, what the Greeks called

akrasia.

Specifically, Aristotle discusses a form of

akrasia

called

malakia,

which is not doing something that you know you should (clearly, procrastination).

3c

Moving a few centuries forward, we see procrastination entering politics. Marcus Tullius Cicero was a major political player around 44

B.C.

His position put him in conflict with Marcus Antonius, better known as Mark Antony, Cleopatra’s lover. In a speech denouncing Mark Antony, Cicero declares:

In rebus gerendis tarditas et procrastinatio odiosae sunt

(“in the conduct of almost every affair slowness and procrastination are hateful”). Perhaps because of Cicero’s advice, or perhaps because Cicero made thirteen other speeches denouncing him,

46

Mark Antony delayed little in killing him.

Then, for a millennium and a half, procrastination made inroads into religion and it is referenced in the texts of every major faith. For example, in the earliest written Buddhist scriptures from the Pali Canon, the monk Utthana Sutta concludes that “Procrastination is moral defilement.”

47

Moving forward seven centuries, the Indian Buddhist Shantideva is still on message, writing in

The Way of the Boddhisattva,

“Death will be so quick to swoop on you; Gather merit till that moment comes!” By the sixteenth century, procrastination starts appearing in English texts without translation. The playwright Robert Greene, for example, wrote in 1584, “You shall find that delay breeds danger, and that procrastination in perils is but the mother of mishap.”

Finally, when the Industrial Revolution came into its own, so did procrastination. In 1751, Samuel Johnson wrote a piece for the weekly periodical

The Rambler,

describing procrastination as “one of the general weaknesses, which, in spite of the instruction of moralists, and the remonstrances of reason, prevail to a greater or less degree in every mind.”

3d

Four years later, Dr. Johnson enshrined the word within his influential English dictionary and, ever since, the term has remained in common use. If procrastination is indeed a core characteristic of humankind, it is acting just as you would expect: it’s maintaining itself as a reoccurring theme in our history books, right from the beginning of the written word.

LOOKING FORWARD

I'd like to end this chapter on the evolution of procrastination with the story of Adam and Eve. They lived in the Garden of Eden, naked and unashamed, fitting in perfectly with nature. Then, in humankind’s first act of disobedience, Adam and Eve bit an apple from the tree of knowledge, and they were cast out by God, forced to survive through agriculture. Though biblical in origin, this story maps perfectly onto the story of evolution as well.

48

In the environment where we evolved, we drank when thirsty, ate when hungry, and worked when motivated. Our urges and what was urgent were the same. When we started to anticipate the future, to plan for it, we put ourselves out of step with our own temperament, and had to act not as nature intended.

49

We are all hardwired with a time horizon that is appropriate for a more ancient and uncertain world, a world where food quickly rots, weather suddenly shifts, and property rights have yet to be invented. The result is that we deal with long-term concerns and opportunities with a mind that is more naturally responsive to the present. With paradise lost and civilization found, we must forever struggle with procrastination.

Bottom line: procrastination is not our fault, but we have to deal with it nonetheless. We encounter procrastination across almost all of life’s domains, from the boardroom to the bedroom, shifting from major to minor. Is it your home life, your finances, or your health that suffers the most from procrastination? Is it your e-mail or TV habit sucking away your productivity? Odds are, not only is the amount of your procrastination increasing, but so is the number of places you are doing it. But I am getting ahead of myself—that’s the subject of the next chapter.

HOW MODERN LIFE ENSURES DISTRACTION

Over the bleached bones and jumbled residues of numerous civilizations are written the pathetic words: Too Late.

MARTIN LUTHER KING JR.

O

ur love affair with the present moment is at the root of procrastination. The fact that we tend to be more impetuous than reasonable is an evolutionary heirloom handed down through a thousand generations. But we can’t blame our neurobiology entirely. Every distraction the modern world offers also exacerbates the mismatch between who we are and what we need to be. This chapter diagnoses the growing divergence between our plans and our impulses. To better write it, I reacquainted myself with an old distraction, purposefully re-infecting myself with what had afflicted me for so long as a student—video games. Gaming’s capacity to absorb and dominate my attention is remarkable. There have been days, which stretched into nights, when I tore myself away from the screen only long enough to cram fast food into my mouth and to take care of my bodily needs. Eventually, I winnowed down every scheduled responsibility or meeting to its barest essentials in order to minimize the time it took away from gaming. My girlfriend viewed it as my mistress. My motto was Just One More Turn.

So, for the purposes of this book, I decided to explore Conquer Club, an online version of Risk©.

1

I hadn’t played the board game since my college days, rolling dice with a few friends and beers, so I found its nostalgic aspect attractive. Also, Conquer Club’s free version only allowed you to play four games at a time, so I believed it would be difficult for it to get out of control. Since you are playing against people around the world, moves are done at all hours and the game progresses at unexpected moments. Consequently, I found myself checking the website fairly often, even when it wasn’t my turn. Suddenly there it was—procrastination, in the familiar form of gaming when I should be working. I could feel the hooks sinking deeper into me and I knew I was taking an extended walk along a sharp precipice—you know, the one you are going to slip over sooner or later (and secretly you are full of anticipation and excitement waiting for the stumble).

My, how quickly addictions reassert themselves. One Friday night, at the end of a long unrewarding work week, with sick kids, and after a trivial tiff with my wife, I felt life owed me more. Perhaps it was a bad idea to then upgrade to the premium version of Conquer Club and play twenty-five games simultaneously.

4a

Periodic checks on the progress of the game became my life’s punctuation marks, the periods capping off any of my tasks. At any break in the day’s flow, I would peek into my games and see what battles had been fought in my absence or perhaps (joy, oh joy!) take my turn. Conquer Club continued to draw me back for weeks after that fateful Friday night. I checked on my games before and after the drives to work and home. It was the last thing I did before I went to sleep, the first thing I did when I woke up; and I dreamt about it in between. Oh, the sacrifices I make for science! But don’t worry about me. Being both a victim and a detective of the fine art of distraction has its advantages. I know how to wind down this obsession, which I will do just after recapturing Kamchatka. While I wait for my turn, let’s talk about why you, along with everyone you know, have likely experienced similar problems.

FULL-IMPULSE DRIVE

One of the elements that made me a slave to Conquer Club corresponds perfectly to the first and strongest findings from my research program: proximity to temptation is one of the deadliest determinants of procrastination.

2

Since every computer offers an opportunity to play, it is hard to keep temptation at bay. The second element is the virulence of the temptation; the more enticing the distraction, the less work we do. Conquer Club followed what is known as a “variable reinforcement schedule”—that is the reward (i.e., reinforcement) occurred at unpredictable times. For over fifty years, ever since B.F. Skinner and C.B. Fester’s 1957 magnum opus

Schedules of Reinforcement,

we have known that such variable patterns of reinforcement are very addictive.

3

Skinner found that from pigeons to primates, we all work much harder for rewards when they are unpredictable but

instantaneous

when they arrive. You can see the power of variable reinforcement in gambling. Slot machines are fine-tuned for addiction because they have these schedules of winning hardwired into them. Every time a grandparent spends the grandkids' inheritance on these one-armed bandits, you can give a nod to the wonderful power of motivational psychology.

4

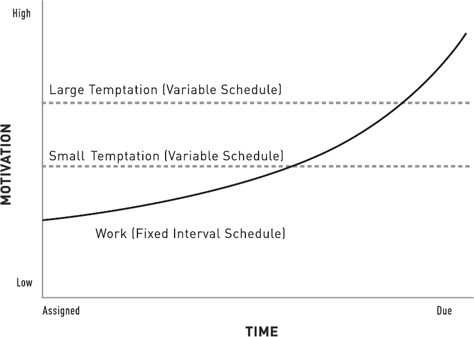

Unfortunately, as my Conquer Club example confirms, the Internet has given rise to a variety of similarly structured diversions. Paradoxically, while the Internet has made it easier for us to work, it has also created a series of behavioral traps that make it harder for us to work at all. In case it helps, I put this in graph form. It shows what comes between our wanting to accomplish a task and our ability to actually complete it.

The graph’s two horizontal dashed bars represent temptations, the lower bar being a small temptation (something nice) and the higher bar being a large one (something great). The solid line that eventually swoops up is the work curve, showing that, as we have seen, most of one’s motivation is reserved until just before the deadline.

5

This is a

fixed interval schedule,

meaning that there is a fixed deadline before your work is assessed and you get “paid.”

4b

On the other hand, variable reinforcement schedules (the horizontal dashed bars representing small and large temptations) exert a constant state of motivation, typically much higher than fixed schedules. The motivation to play is always there and doesn’t go away. The more attractive we make the temptation (making it large instead of small), the higher its bar moves and the longer it takes for the competing work line to become the dominant choice. So, we can see that when the allure of temptations rises, so does procrastination.

RAISING THE BAR

In award-winning research, Vas Taras, a professor from the University of North Carolina, and I assembled a database that tracked changes in the world’s culture over the last forty years.

6

It required piecing together hundreds of studies from social scientists of all stripes who used dozens of different scales. What we found was that as countries “modernize,” they start to converge around a set of values typical of Western free market economies. One major finding was that the world has become more individualistic: people look after themselves with less concern for others. Another was that modernization brings with it procrastination. As our economies have grown over the last few decades, we have experienced a fivefold increase in chronic procrastination. In the 1970s, 4 to 5 percent of people surveyed indicated that they considered procrastination a key personal characteristic. Today, that figure is between 20 and 25 percent, the logical consequence of filling our lives with ever more enticing temptations.

Consider how the world was transformed during the last century. In 1911, William Bagley, writing in

The Craftmanship of Teaching,

described the “hammock on the porch,” the “fascinating novel,” and the “happy company of friends” as the “seductive siren call of change and diversion, that evil spirit of procrastination!” Bagley’s temptations, though real, were relatively pedestrian compared to what was to come. Also in 1911, the first film studio opened in Hollywood, and the next few decades saw the rise of multi-million-dollar productions and multi-millionaire movie stars, along with their scandals; both Charlie Chaplin and Errol Flynn—the comic tramp and the romantic swashbuckler—seemed to like their women a little bit younger than the law allowed. The spectacle of Cecil B. DeMille’s

The Ten Commandments

hooked viewing audiences, and by the 1930s, the popular press was referring to movies as a common form of procrastination.

7

Still, you had to leave your home or office to see the silver screen. But not for long. The end of the Second World War coincided with the development of television, and the number of Americans with TVs leaped from 9 percent to 65 percent between 1950 and 1955. During popular show times, streets would empty and stores would shut so that everyone could tune into episodes of

I Love Lucy.

By 1962, with television sets now in 90 percent of American homes,

Popular Science

published a book digest, “How to Gain an Extra Hour Every Day,” connecting television watching to procrastination.

8

In the mid-1970s, a new temptation emerged on the scene. I was eight years old when Pong, the first successful video game, was introduced to our household. My father hooked up one end of the game box to our black-and-white TV and the other end to two “paddles” that were nothing more than knobs on cords. You turned your knob and a small bar moved vertically on either the left or right side of the screen, depending on which paddle you had. If a moving electronic ball hit your paddle, it was deflected back to the other side of the screen for your opponent to return. That’s it, but it was magic and I loved it. Sure enough, by 1983, psychology texts were reporting video gaming in the list of typical procrastination behaviors.

9

Having looked at some historical baselines for comparison, you should be able to see why procrastination has risen to today’s levels. While the pleasure derived from working has remained fairly constant over the decades, the power of distractions only seems to increase. The temptation bar in Skinner’s graph is raised ever higher, while the work curve remains the same. Let’s reconsider today’s video games, which make Pong laughable by comparison. Unfathomably more advanced, these games are the product of untold millions of programming hours, and tax the capacity of even the most advanced computer systems. They beat hands-down anything that Bagley wrote about. Many people play anywhere, anytime—it is not uncommon for students to engage in head-to-head online games during university lectures.

10

Furthermore, as good as these games are, they are getting better. With each evolving iteration of Grand Theft Auto, Guitar Hero, or World of Warcraft, choosing

not

to procrastinate becomes harder. The graphics, the story, the action, the console—all of them advance. In the battle for your attention, it is as if work is still fighting with bows and arrows while gaming has upgraded to auto-cannons, sniper rifles, and grenade launchers. Consequently, it is becoming increasingly common for people of all ages to become consumed by games, and intervention centers are proliferating to treat video game addiction. In Korea, for example, about 10 percent of young people show advanced signs of addiction, developing up to seventeen-hour-a-day habits. In response, the government has sponsored 240 counselling centers or hospital programs. There are even resources for particular games, such as www.WoWdetox.com, which is dedicated to World of Warcraft players as well as their spouses, typically called Warcraft widows.

What is more shocking is that there are worse creatures than video games for inciting procrastination. The worst isn’t getting a bite to eat or napping, though they remain popular choices. The king of distraction—and there is only one—is television.

11

Since its halcyon years in the 1950s, television has continued to perfect itself, gaining all the features it needs to win the competition for our time. The magic of the remote allows us to change channels without moving. The advent of cable and satellite has ensured that there is always at least one available channel that reliably caters to our tastes. And with multiple television sets throughout the house—more TVs than people according to Nielsen Media Research—we can watch our shows anywhere we like. If our interest in a particular program flags even momentarily—zappp!—we are off to other worlds in this 500-channel universe. So attractive is television that we are often guilty of over-consumption, feeling TV'd out and wishing at day’s end that we'd watched a little less.

12

Most Americans spend about half of their leisure hours in television’s glow. Other nations aren’t far behind. According to the latest national census data, Americans watch an average of 4.7 hours per day, beating out Canadians, who watch 3.3 hours per day. The average Thai spends 2.9 hours in front of the tube; a Brit, 2.6 hours, and a Finn, 2.1 hours. Reading, for comparison’s sake, clocks in at an international average of 24 minutes a day. This means, of course, that you have likely been plugging through this book for about three months now.

Worse still, as with video games, TV is getting more and more attractive. Not only is the hardware becoming sleeker, and higher-tech, but your options of what to watch are also stepping up. Season box sets are commonplace, as are digital video recorders (DVRs). These DVRs allow you to record multiple programs simultaneously, store hundreds of hours, keep track of what you have watched, and help you find desirable episodes. Watching scheduled TV seems primitive today. The future promises even more. As television continues to evolve, viewing options become almost endless. For example, the technology already exists to download any movie in less than a second. When a fraction of that power becomes available to the ordinary household, we can expect our TV viewing to rise correspondingly. Any movie, any show, any clip, can be seen by anyone, almost anywhere, all at an insanely crisp resolution. Inevitably, as television pumps up, it muscles out the rest of life. It is already happening. For every country with data, the amount of television watching has increased. In just eight years, from 2000 to 2008, TV watching in the United States went from 4.1 to 4.7 hours, a 15 percent increase. Since time is finite, everything else must suffer—and suffer it does.

13

It’s not just chores that we put off in favor of tele-vision—it’s eating with the family or connecting with friends.