The Good and Evil Serpent (62 page)

Read The Good and Evil Serpent Online

Authors: James H. Charlesworth

Life

Since the snake is forced to swallow its food whole

and usually alive

(cf. 2.9), the serpent often symbolizes the embodiment of life. Whereas the lion kills and then eats sections of the kill periodically, the serpent often does not kill but swallows its prey alive and all at once. I have seen a snake with another snake, still alive and alert (with the mesmerizing unblinking eye), protruding from the victor’s mouth. Thus, the snake does not always kill its prey; but, expanding its jaws perhaps five times the width of its neck, it absorbs life, swallowing it whole. Thus, the serpent becomes the symbol of life.

363

In

Das Schlangensymbol

, Egli devoted a chapter to the serpent as the symbol of life.

364

In Arabic,

hayya

means “snake,”

hayy

denotes “living,” and

baydh

indicates “life.”

365

In Persian,

haydt

denotes “life” and

haiydt

indicates “serpents (the plural of

haiyat).”

366

In Syriac,

h

e

wd

is the verb “to be,” but

hayye

signifies “life,” and

hewyd

denotes “snake.”

367

The sounds are similar, even if we might become lost searching for etymological links. Perhaps among some Semites “snake” and “life” were associated not only symbolically but also linguistically; in many Semitic languages and dialects, the sound of “snake” echoes the word “life.”

368

In Babylonian religion, Marduk struggles against and eventually slays the serpent-like (or dragon) Tiamat. Likewise in the Hebrew Scriptures (Old Testament) and the Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, the Creator is mythologically portrayed in a cosmic struggle with Leviathan, the sea serpent or dragon (see

Appendix I

). Also, in ancient Egyptian religion, Me-hen, the serpent, was the god who protected Re on his journey through the sky. Likewise, in Indian mythology, the serpent Sesa is the companion of Vishnu, the god of preservation.

369

In ways conceptually odd for post-Enlightenment Western thinkers, the slaying of the dragon, or serpent, provides life.

Nourishment necessary for life is also often associated with the serpent. In many cultures, especially in Melanesia and South America, the serpent is the one who informs humans of the plants that are edible. In Egypt, the goddess of agriculture was revered as a serpent. In Southwest Asia, in China, and among the Hopi Indians, the serpent is the deity who provides rain. The Aztec feathered serpent, Quetzalcoatl, becomes flesh, sacrifices itself for humans, and—according to the Dresden Codex—is the god that is “the cloud and his blood is the rain which will enable the maize to grow and mankind to live from the maize.”

370

The serpent symbolizes life and sustenance.

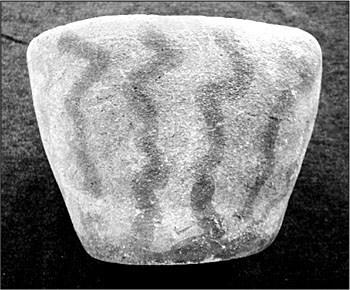

Figure 73

. Ceramic Middle Bronze Pot with Serpents. Hebron, time of Abraham. JHC Collection

The authors of the biblical and related literatures knew the snake’s mys-teriousness and chthonic nature. They thus chose it as an ideal creature for symbolism. The snake’s ability to discard its old skin and grow more youthful evoked reflections by many humans on the fundamental relation between life and death.

371

According to the author of Numbers 21, and John 3 (as we shall see), the serpent represents life.

Water

The snake is amphibious (cf. 2.16); it can move over, through, and under water. Thus, it can symbolize water (both salt water and fresh water can be the snake’s habitat). Numerous Greek names for a “snake” are associated with water (see

Appendix II

); for example, the

Columber natrix

is the “water snake” ( [see

[see

Appendix II

, no. 36]). Not only in Greek thought and myth but also in Etruscan, Roman, Egyptian, and Mesopotamian cultures, the serpent can symbolize water.

372

In discussing the serpent as a symbol of chaos and the cosmos, we confronted the many connections between this creature and water. The symbolism is grounded in reality. The snake can live in salt water and fresh water; it thrives in marshy land and in wetlands. It is clear why the serpent came to symbolize water, and why the hieroglyphic symbols for snake and water are so similar.

It is evident that the ancient symbol for water may be a double entendre: the serpent was included in the water symbol. The complex wavy line is prehistoric. Indeed, one of the oldest graphemes is a wavy line or zigzag. It appears in Paleolithic times and is prominent in the Levant and Asia Minor. In Sumerian cuneiform and Egyptian hieroglyphics, the ideograph for “water” is a zigzag or wavy line. Zigzags or waves decorate vessels on Crete, Asia Minor, ancient Palestine, and elsewhere. As A. Golan shows: “The zigzag as a graphic symbol had a specific meaning: it designated snake or water.”

373

The snake is often associated, from early times, with springs and gushing water.

374

The snake as a symbol of water is also evident when one observes that snakes and fish, so dissimilar, are ideologically associated and appear together iconographically and mythologically.

375

Of course, there is also the water snake that counters any suggestion that the serpent belongs on land and the fish in the water.

376

In Sumerian,

mush-ki

signified “snake-fish,” and in Phoenician

nun

denoted “fish” as well as “water snake.”

377

Apparently, the fascination with snake gods waned in Mesopotamia, beginning in the first half of the second millennium

BCE

.

378

The Native Americans believed in a large serpent. He is often portrayed as a personification of water. According to the Ojibwa, he is connected with the primordial flood. According to the Hopi, the dance of their priests, holding rattlesnakes in their mouths, can produce rain. Although in China the snake is usually feared, the dragon is understood as one who can provide rain.

379

MacCulloch suggested that the mythic association of the serpent with water and the waters is “either because some species lived in or near them or in marshy ground, or because the sinuous course and appearance of a serpent resembled those of a river.”

380

Two Bactrian seal-stones, one in the Louvre and the other in the Kovacs Collection, were found in East Iran. The male figure on these seal-stones is similar to a man with serpents as arms known on other seals. According to G. Azarpay, this glyptic tradition suggests that the serpent symbolized longevity, immortality, fertility, and the fruitfulness of plants; moreover, the serpent also has phallic meaning and serves “as a reference to hidden sources of water.”

381

Adonijah, rivaling Solomon for David’s throne, made sacrifices by a place called “the Serpent’s Stone” (Heb.:

‘eben hazzohelet

[1 Kgs 1:9]).

382

This stone is near En Rogel, which is usually identified with the spring at the southern end of the Kidron Valley where it meets the Hinnom Valley. Since “En” denotes a spring or well, in this ancient tradition we find an association of the concept of serpent with water.

Assyrians and Babylonians believed in the serpent god of the Euphrates or the deep. Leviathan and Rahab are monstrous dragon-serpents of the deep waters.

383

In the Ugaritic literature, for example, we find the statement that the Tanninim are “in the sea.”

384

Psalm 74 contains a parallel thought to Babylonian and Assyrian myths. The Hebrew poet likewise identifies Leviathan with the flood and the mighty waters:

You, you broke the heads of Leviathan in pieces,

You gave him as food to the people inhabiting the wilderness.

You, you broke open the fountain and the flood (or river);

You, you dried up mighty rivers. [Ps 74:14]

Another important biblical passage that clarifies the link between water and serpent symbolism is Isaiah 27:1 (TANAKH):

In that day the Lord will punish,

With His great, cruel, mighty sword

Leviathan, the Elusive Serpent—

Leviathan, the Twisting Serpent;

He will slay the Dragon of the sea.

In this passage it seems evident that the serpent personifies Assyria. Note the insightful comments by Le Grande Davies: “It is quite evident that Isa 27:1 used

Leviathan-nahash

in a general historical context as the symbol of the once powerful Assyria, about to be destroyed. What appeared in the texts was a mythological symbolical personification of opposition and death to ancient Israel” (p. 43). Thus, the serpent as primordially a symbol of water has been shifted to a historical context.

In Arabia and Palmyra, the flow of wells or springs is imagined in lore to be controlled by serpents.

385

The concept of a serpent as present in such life-giving locales

(genius loci)

is well known in Greek and Roman times.

386

Clearly, not only in the Hellenistic and Roman periods but also in most world cultures, the sea, rivers, and springs were revered, even considered part of worship; the serpent is almost always present explicitly or implicitly in such contexts.

387

In the previous chapters, we have studied the many pots or vessels with serpents depicted on them, usually with their heads near or on the rim.

388

The serpents may have been placed there to symbolize water and not only the protection of it, along with other liquids.

Soul (and Personal Names)

The snake was perceived to be chthonic,

389

immortal (or the creature that did not die),

390

and without distorting appendages;

391

hence, Greeks and Romans imagined the serpent as the animal that represented the soul. This perception derived primarily from its mysterious chthonic character. It could descend into the earth; it is there that the souls of the dead resided. Since snakes frequent tombs and graves,

392

the ancient Greeks, and others, associated the serpent with the soul of the departed.

393

Evidence that the serpent was admired in antiquity is found in the names of different individuals. We find “dove” (Yona), “bee” (Deborah), “sheep” (Rachel), but also “adder” (Shepiphan) and “serpent” (Nachash), especially in 1 Samuel 11:1.

394

Health and Healing

Since the snake is never perceived to be in pain or sick and rejuvenates itself through ecdysis or molting (cf. 2.17), it symbolized health and healing.

395

Maringer studied serpent images from the Paleolithic (at least 30,000 years before the present) to the Iron Ages. He perceived that, as early as the Iron Age, the serpent symbolized healing and medical properties. He surmised this meaning of serpent iconography because of the discovery of serpent images near thermal healing springs.

396