The Good and Evil Serpent (58 page)

Read The Good and Evil Serpent Online

Authors: James H. Charlesworth

In ancient times, the serpent is sometimes positioned entwined around a tree, with a piece of fruit on each side of its head and with the sun to the left and the moon to the right.

276

The author, or at least those who saw this symbol, thought about the ways the serpent helped the human conceive the cosmos.

Epiphanius mentions a gnostic system in which the archon of the lowest sphere is a dragon that swallows the souls without gnosis.

277

As Hans Jonas perceived, the serpent often symbolizes the cosmos and gnosis.

278

Serpents formed into a caduceus are featured on the Zodiacal Disk from Brindisi.

279

The heavens are sometimes imagined in the Hellenistic and Roman world as snakes. They appear either as stars or the stars are their symbols.

280

These reflections disclose another meaning of the incense stands found at Beth Shan. The serpents and birds probably symbolized spring and the return of fertility. They also signified, at least to some of the Canaanites, something more. An informed imagination allows the human who participated in the serpent cult at Beth Shan often to perceive the serpent and dove as symbolizing the cosmos. Most likely for many in ancient Palestine, especially the Canaanites, the serpent symbolized the chthonic world, the human the earthly realm, and the dove the heavenly spheres.

The symbolism can be reversed. The snake could be depicted as threatening the dove, as in the Roman sculpture of a girl protecting a dove from a snake.

281

Then, the cosmic dimension of serpent iconography and symbol-ogy has been lost.

Shelley perspicaciously grasped the cosmic symbolic significance of the serpent. Note his words:

When priests and kings dissemble

In smiles or frowns their fierce disquietude;

When round pure hearts a host of hopes assemble;

The

Snake

and Eagle meet—the world’s foundations tremble!

282

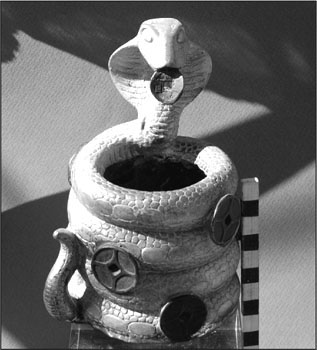

Figure 70

. China. Gold Cobra, about five hundred years old. JHC Collection

Jerusalem was built by Solomon and his descendants to replicate the cosmic garden: Eden, or Paradise. The western side of the Kidron Valley was sculptured into “a cascade of gardens and parks.” As L. E. Stager states: “The original Temple of Solomon was a mythopoeic realization of heaven on earth, of Paradise, the Garden of Eden.”

283

Would snakes have not crept into this earthly paradise, and would that fact not have marred the symbolism? Was not the snake banished from the Garden of Eden? Surely, not only the author of Genesis 2:4b-3:24 (the Yahwist known as “J”), but many Israelites knew that, according to the Genesis myth, the serpent was never banished from Eden. Why would the Yahwist conclude his story with the expulsion of only the humans: “So he drove out the man ” (Gen 3:22–24)? If the Yahwist wrote at a time when Jerusalem was richly endowed with flowering parks and gardens, undoubtedly an attractive habitat for crawling things like serpents, would he not have been motivated to keep the snake in the edited story also?

” (Gen 3:22–24)? If the Yahwist wrote at a time when Jerusalem was richly endowed with flowering parks and gardens, undoubtedly an attractive habitat for crawling things like serpents, would he not have been motivated to keep the snake in the edited story also?

284

Chronos

The snake is elongated and limbless (cf. 2.5). When shaped into a line, it can symbolize linear time. The ubiquitous and circuitous Ouroboros frequently, and perhaps fundamentally, symbolized time and eternity; it was not only beginning but also end. Time was often perceived, as among the Stoics, as circular.

The shape of the serpent symbolized oneness, unity, and completion. It could also symbolize time for the ancients.

In south-central Ohio there is a “Serpent Mound.” It is a more than 400-meter-long image of a snake. The date now suggested, thanks to radiocarbon dating, is 900 to 1600

CE

. Some experts believe that the Serpent Mound is aligned with the summer solstice sunset and perhaps with the winter solstice sunrise. The dating of wood charcoal found in situ points to circa 1070. Is it mere coincidence that Halley’s comet appeared in 1066?

285

Kingship

The snake shows no fear (cf. 2.15) and appears never to age and to be immortal (cf. 2.17). It (he, she) has a regal bearing (cf. 2.19 and 2.28), is physiologically unlike humans (and most creatures; cf. 2.23), and can administer death (cf. 2.20). These physical characteristics of the snake lie behind the perception of the serpent as denoting and connoting kingship. Analogous to the concept of the serpent symbolizing wisdom is the depiction of the “king” or ruler as protected or framed by serpents.

From Mesopotamia come mythological scenes in bas-relief on a steatite basin. These depict a man holding two serpents that are larger than he; they most likely date from the end of the fourth millennium

BCE

.

286

Likewise, from Mesopotamia (but from c. 2275 to 2260

BCE)

comes a libation beaker that shows two serpents coiled around an upright staff. On both sides one can see a winged dragon with a serpent’s head topped by a horned crown; it has front legs with lion paws and back legs with bird’s claws.

287

Assyrian seals depict a serpent, thus representing godly and kingly powers and protection.

In various, sometimes antithetical, ways, the serpent represented “power.” For Isaiah, the threatening powers were Leviathan and a dragon (Isa 27:1). For the Egyptians the uraeus, an aroused cobra or asp, was placed in royal palaces and on the heads of pharaohs to symbolize their godly and kingly powers (see

Figs. 24

and

25

). It is thus no surprise to see on Tutankhamen’s throne winged serpents rising majestically from the back.

In the Greek world, the supreme God was Zeus and in the Latin world Jupiter (

Fig. 57

). He was sometimes challenged by the popularity of Asclepius, who promised health, healing, and immortality (e.g.,

Figs. 1

and

58

). Both supreme gods appear with, and sometimes as, serpents and they sometimes conflate or merge (

Fig. 11

). Both were perceived to have kingly powers, especially Zeus, who is sometimes depicted as Zeus Meilichios.

In myths, especially in the Greek and Roman world, the divine kings were depicted as serpents or had serpent features.

288

Citing Pausanias (1.36.1), W. R. Halliday pointed out: “These snake kings were sometimes the slayer of snakes. Kychreus appeared in snake form at the battle of Salamis to help the patriot Greeks.”

289

Long ago, Wellhausen pointed out that the princely family of Taiji ofthe Arabian dynasty in Edessa and the kings of Abyssinia (Ethiopia) were supported by lore that claimed they were descended from serpents.

290

In Taiwan, the Paiwan chieftains during festivals are portrayed with a serpent. As is well known, the dragon (a mythically large serpent) signified the emperor in China.

Divinity

The apparent invisibility and elusiveness of the snake have evoked reflections on its divinity, since God has been experienced as not only invisible but also elusive (cf. 2.13). The same reflections apply to the snake’s ability to symbolize the hidden one (cf. 2.14). The snake also appears to show no emotion (cf. 2.21); its expressionlessness suggests superiority, even divinity. The snake can only hiss and is without voice; its inability to make sounds like other animals might lead to reflections that it lives within the world of silence in which communication with God is possible (cf. 2.3). The snake’s simulated smile might lead to reflections that it is at peace because it is one with the source of peace: God. The ability of the snake to forgo eating for months elicited reflections on its divinity (cf. 2.10). The fact that the snake is rare and unusual since it does not smell and is thus invisible and elusive (cf. 2.29) helped stimulate reflections on ways the serpent symbolized God.

In the preceding study, we saw ample evidence of ophiolatry, the worship of the snake.

291

Surely, many of the snakes made of gold and silver once belonged to an ophiolater (a worshipper of snakes). The second millennium

BCE

was a time of snake worshipping, and not only worshipping through snakes; the best examples are on Crete with the Minoan snake goddesses (or priestesses) and in the Canaanite snake cults at Beth Shan and Hazor. The Sinaitic Inscriptions contain a reference to a goddess of snakes, “the Serpent-Lady, my mistress.”

292

As H. Frankfort showed, the entwined serpents that form a caduceus on the steatite Gudea Vase from Lagash symbolized the god Ningizzida.

293

According to the author of the

Prayer of Jacob

, the Father of the Patriarchs, the Creator, sits upon “the s[er]pen[t] gods.”

294

According to Eusebius in his

Preparation for the Gospel

, Sanchuni-athon, through Philo of Byblos’ translation, explains how the serpent symbolizes divinity:

The nature then of the dragon and of serpents Tauthus himself regarded as divine, and so again after him did the Phoenicians and Egyptians: for this animal was declared by him to be of all reptiles most full of breath, and fiery.… It is also most long-lived, and its nature is to put off its old skin, and so not only to grow young again, but also to assume a larger growth; and after it has fulfilled its appointed measure of age, it is self-consumed.

295

We are also dependent on Eusebius for the claim of the Egyptian scribe Epeis, which was noted earlier, that the “first and most divine being is a serpent with the form of a hawk.”

296

In Greece, as we have demonstrated in

Chapter 4

, gods appear with serpents and as serpents. Earlier in Egypt the same was widespread; in hieroglyphics the snake is drawn to indicate ideograms, including “goddesses.”

297

The hieroglyphic sign of a snake with horns, probably a horned viper

(f)

, combined with

t

dejotes a “viper,” and as

f’g.t

(with a horned viper at the beginning and a cobra at the end) specifies the goddess Nech-bet.

298

The “living god” Netjerankh is represented as an upright snake.

299

Josephus reports that the Egyptians believe that one who is bitten by an asp is “happy” and approved by the gods

(Against Apion

2.7).

We need to add what has already been said about Zeus as a serpent. The Greeks believed that he transformed himself into a snake to woo his bride.

300

Herodotus

(Hist

. 2.74) reports that “sacred snakes” were “buried in the sanctuary of Zeus.”

In the Agora Museum in Athens, one can see a ceramic plaque from the seventh century

BCE

(no. 21). It shows a goddess with both hands raised. On each side of her is a raised serpent.

In Persia, according to the historian Philo of Byblos, who wrote about the same time as the author of the Fourth Gospel, Zoroaster was sometimes celebrated and honored as a god who had the form of a serpent, but a hawk’s head. According to this Philo, Zoroaster, in his teachings, held that the one

who has the head of a hawk is god. He is the first, imperishable, everlasting, unbegotten, undivided, incomparable, the director of everything beautiful, the one who cannot be bribed, the best of the good, the wisest of the wise. He is also father of order and justice, self-taught, and without artifice and perfect and wise and he alone discovered the sacred nature.

301