The Good and Evil Serpent (55 page)

Read The Good and Evil Serpent Online

Authors: James H. Charlesworth

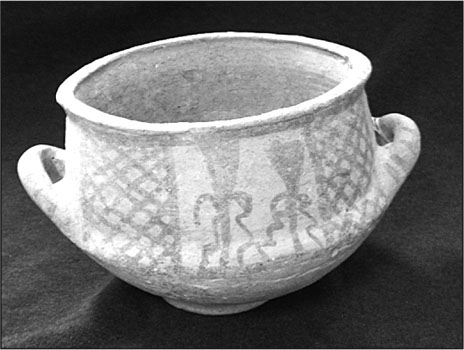

While the trees are stylized, they remain unmistakable. The serpents appear with large eyes, as in other examples from the second millennium

BCE

. The serpents seem to be depicted eating something (probably fruit that is not shown) at the base of the triangular upper part of the tree. If the one who painted the bowl or if those who used or saw it imagined this interpretation, then we have iconography and symbolism similar to and prior to the Yahwist who composed Genesis 3 from earlier cultures such as the one represented by this bowl. Note, especially, that the serpents are depicted upright and standing, but no feet are drawn.

Figure 68

. Ceramic Late Bronze Pot Probably with Tree and Serpents; from Betula, near Beth Shan. JHC Collection

Most likely the serpent goddesses or priestesses of ancient Crete also symbolized the link between the serpent and the fruitfulness of nature. The images of a man holding two serpents upright, in a fashion reminiscent of the Minoan goddesses or priestesses, also seems to symbolize fruitfulness.

203

The dove and serpents on the Canaanite cult stands found at Beth Shan probably, as indicated earlier, denoted the serpent’s relation with fruitfulness. The spring harvest festivals often lift up the serpent as a symbol of the earth’s return to rejuvenation (viz. with Agathadaimon and in the Demeter festivals in Athens in which Demeter and the serpent were intertwined). The power of the serpent to symbolize fruitfulness is linked with its presence and role in creation in so many of the world’s myths (as, e.g., in Persephone and Zeus Meilichios).

Energy and Power

Although the snake is without legs (now), it is amazingly swift and energetic (cf. 2.1).

204

The serpent is strong and powerful (see

Fig. 13

). From the ancients we learn (of a myth) that there are snakes in India that can strangle and swallow a full-grown elephant. This mythic lore is grounded in the awesome power of snakes. They seem to be one big muscle (and, to some ancients, symbolic, as just said, of a fully erect phallus). It is clear why H. Egli in

Das Schlangensymbol

devoted a chapter to the serpent as the symbol of power.

205

Cassandra, Helenus, Melampus, and Iamos received power from serpents when they were sleeping.

206

W. Foerster pointed to the “twofold character of the serpent.” The animal represented the “primal power.” He offered the opinion that this power resided in the ability of the snake to kill.

207

This interpretation is typically one-sided, as Foerster stressed only the negative features of ophidian symbolism. Snakes are characteristically docile. Hence, the Rabbis, observing that a poisonous snake will not bite if not aroused, advised that even if a snake is coiled around one’s heel, one should still continue to recite the

Amidah (b. Ber

. 5:1) and, if one is about to be attacked, one may defend oneself while praying (b.

Ber

. 9a).

208

When Foerster claimed that the power of the serpent resided only in its ability to kill, he apparently never felt awe before an upraised king cobra or held a part of a two-hundred-pound boa. If one studies the anguipede Giants on the Pergamum altar,

209

or the massive stone Giants with one anguipede in Agrippa’s Odeion in the Agora of Athens,

210

or examines the ancient depictions of Laocoon, one feels the power of serpent iconography. One does think immediately about the lethal bite of a snake.

What is stressed iconographically is the awesome power of the muscular and speedy serpent. The artists bring out the power of serpent symbolism by revealing the way the anguipede Giants strangle the gods and highlighting the tensed and mighty muscles of Laocoon. Today one associates the power of a snake with its ability to administer swift death, but in ancient iconography more stress is placed on the serpent’s awesomeness and mys-teriousness, and its ability to avoid illness and regain the look of youth at least once each year.

In interpreting Job, the Rabbis offered an example of God’s power. They tell a story. God prepared a dragon-snake

a dragon-snake for a female gazelle whose birth canal was too narrow for easy birth. The snake bites her in the birth canal. It subsequently becomes stretched, and the gazelle finally gives birth

for a female gazelle whose birth canal was too narrow for easy birth. The snake bites her in the birth canal. It subsequently becomes stretched, and the gazelle finally gives birth

(b. B. Bat

. 16b). The bite of the dragon-snake did not kill; it possessed the power to assist God in enabling the gazelle to give birth.

On the western wall in the Greek Orthodox Church at Capernaum, one may look up to see an attractive new mural. Christ sits enthroned in judgment. On his left and below him are two large figures. One is the earth

(ge)

. How is Christ depicted? He sits on two lions and holds a serpent in his right hand. The other “being” judged is the sea

(thalassa)

. How is she portrayed? She is also with a serpent. What do these ophidian symbols represent? I directed this question to a young monk in the Greek Orthodox Church. Pondering Greek traditions, he instantaneously answered, “power.”

Today fast and powerful sports cars are sometimes given the name “cobra.” The Alfa Romeo’s logo has the sign of the upright serpent on it. Lingering, sometimes unperceived, are examples of serpent symbolism that are positive. The serpent continues to symbolize power.

Beauty

The snake is simply one of the most beautifully decorated creatures (cf. 2.19; also see

Figs. 10

,

15

,

18

). If it were not for the fear of an asp, a cobra, a black mamba, and a Boomslang, the snake would be widely hailed as one of the most attractive creatures on earth. While traveling in the Sinai in 1877, A. F. Buxton saw a snake he described as “about 2 feet long, of a most gorgeous colouring.” In his journals he described it as “lame-coloured.”

211

In December 2002, Natalie Angier, in “Venomous and Sublime: The Viper Tells Its Tale,” wrote her subjective reflections on vipers: “Is there anything cooler than a snake or more evocative of such a rich sinusoidal range of sensations? Snakes are beckoning. Snakes are terrifying. Snakes are elegant, their skins like poured geometry.” In the same publication, Dr. Jonathan A. Campbell of the University of Texas at Arlington added, “Even those who don’t like snakes have to admit their beauty.”

212

Those who say they despise snakes are often found staring, somewhat mesmerized, at a captive snake. If the snake is so horrible, as most assume today, then why are there often four people in a zoo standing watching elephants, six observing lions or bears, but dozens investing their time within a serpentarium?

One reason we all watch snakes, in a place safe for us, is our fascination with the snake and its innate beauty. As I said at the beginning of this work, the large golden king cobra that rose and looked me in the eye when I had just become a teenager was, and remains, one of the most beautiful creatures I have ever confronted.

The Greek and Roman women who wore the gold bracelets and rings with serpents depicted in the most realistic manner most likely chose them—or were given the jewelry as a gift—because of the serpent’s beauty. As we have seen, this serpentine jewelry is astonishingly beautiful and often realistic (see

Figs. 34

,

35

; cf.

Figs. 18

,

37

,

39

). In fact, the usual Greek noun for “serpent,”

ophis

, also signifies a bracelet in the form of a snake.

213

Josephus apparently thought the serpent provided appropriate imagery for describing beauty. He mentions that the sumptuous linen garment of the high priest was loosely woven as if “were the skin of a serpent” (Ant 3.7.2).

Goodness

The snake does not aggressively attack, except for food. It protects humans from harmful animals (cf. 2.27) and helps cultivate the garden (cf. 2.26); hence, the serpent symbolizes goodness.

When I was in Galilee, in November 2002, while the present work was in its final stages, I encountered two snakes. One was on the Mount of Beatitudes. An Arab had cleared some brush and was burning it. A small gray snake emerged. It was frightened and sought every avenue for escape. The next day, while driving from Capernaum to Gamla, I sped past a long black object on the road. I stopped the car and slowly backed up. I found my camera and slid out of the car; soon I was about 6 meters in front of a large black snake. It raised its head, moved its body in contradictory directions, and then shot away to my right, to hide—thus, proving that, for snakes, as for most animals, the first line of defense is avoidance.

214

The farmers in the Golan protect these large harmless snakes because they rid their farms of mice and other harmful creatures. For the farmers, long ago and now, the snake was often a friend, and a symbol of goodness. The snake in the Golan is called “Bashan” by the Arabs (cf.

Appendix I

).

Perhaps the best example of the serpent as the symbol of goodness is the ubiquitous Agathadaimon, the good serpent that was so popular in many cities,

215

especially at Alexandria and Pompeii (see

Figs. 34

–

36

). In the Agora Museum in Athens one can see a bronze Agathadaimon with a human face and long hair. It is almost 8 centimeters high and dates from the Roman Period (Box 50). The goddess Isis, who is often shown with a serpentine lower torso, also represents goodness (see

Figs. 50

,

51

). Athena symbolized wisdom and might in battle; the ancients often depicted her with serpents on her chest (

Fig. 52

). Sometimes Athena appears as Hy-gieia, as in the phrase “Athena Hygieia,” and with realistic snakes on her breastplate.

216

In Palmyra, the statue of the goddess Allat is influenced by those of Athena; notably, she is depicted with curled snakes on her upper garment.

217

Among Aphrodite’s many attributes—beside might, beauty, and sex—is goodness; recall the serpent sometimes disclosed on her thigh (see

Fig. 23

). Rabbi Shimon ben-Menasya lamented that the serpent could have been “a great servant.”

218

He also claimed: “[T]wo good serpents”

would have been given to each Israelite, to serve them and assist in their work.

would have been given to each Israelite, to serve them and assist in their work.

219

In analyzing the votive feet and the statues of Asclepius and Hygieia found in Roman Caesarea Maritima, R. Gersht rightly stressed that the serpent “was perceived not only as the being that is able to heal, like a dog, with the licks of his tongue, but also as the embodiment of the mildness, goodness and the philanthropy of the god and his daughter.”

220

Such insights bring to memory Plutarch’s report that Demosthenes pronounced Asclepius’ name so that the accent fell not on the final syllable, as is customary, but on the third syllable so that the god was perceived to be “mild”

(epios).

221