The Good and Evil Serpent (54 page)

Read The Good and Evil Serpent Online

Authors: James H. Charlesworth

While the snake is almost always regarded as a symbol of Satan or evil today, the positive meaning of ophidian symbolism frequently remains unperceived. The serpent is highlighted in the signs of pharmacies and medical colleges (as just intimated). Quite surprisingly, a drawing of three intertwined snakes (like the Tripod of Plataea) appears as an embellishment of the first word in “T” in numerous chapters in Sister Theotekni’s

Meteora: The Rocky Forest of Greece.

182

On Mount Nebo, the cross almost always is shown with a serpent draped over it—clearly an interpretation of John 3 in light of Numbers 21.

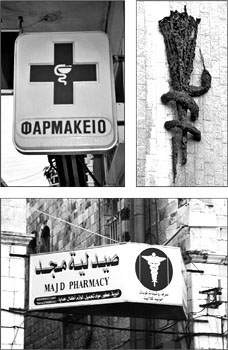

Figure 67

. Serpent Signs in Greece (fop

left)

, West Jerusalem (Israel Medical Association,

top right)

, East Jerusalem

(bottom)

. JHC

While some of the data we have collected as serpent symbolism cannot be neatly arranged under only one of these categories, most are easily placed in one, or two, of the forty-five categories. There is now no basis to doubt that the snake, above all animals, has provided the human with the most varied and complex symbology. As mentioned in

Chapter 2

, we need to recall that at the same time the serpent may symbolize opposites (double entendre) as with the uraeus and caduceus. The bearer of evil is neutralized (and perhaps superseded) by the bearer of good. Each is symbolized as a serpent. Perhaps the first is an evil snake, the second a benevolent serpent.

Phallus, Procreation, Fertility, and Good Sex

The male serpent has two phalli (each is a hemipenes). The female produces an abundant number of offspring, as Aristotle knew (but he may not have known that the reticulated python can produce a clutch of one hundred eggs).

183

These two characteristics—the male’s two penises and the female’s fecundity—make the snake an ideal symbol of sex and fertility (cf. 2.7). We have previously mentioned that the physical appearance of the snake, especially when aroused, is reminiscent of the engorged phallus (cf. 2.5). As many have observed, and the Freudians popularized myopi-cally, the serpent can remind the viewer of the lingam. Additional symbolic meanings of the serpent, therefore, are procreation, fertility, good sex, and power.

In the ancient Near East, the serpent played a part in sacred marriages.

184

According to Eusebius in his

Preparation for the Gospel

, Porphyry wrote: “[The] phallic Hermes represents vigour, but also indicates the generative law that pervades all things.”

185

The bronze serpent pendant found in or near Jerusalem is also strikingly reminiscent of the phallus. I have seen many images of the hand and the phallus as amulets that were worn by soldiers who lived in the first century; some of these images seem to be Jewish because the marks of circumcision are clear. I have not found an amulet with the depiction of a hand, a phallus, and a serpent. Such an amulet would strikingly denote serpent symbolism as representing power. Perhaps someday one will show up in the antiquities shops of Old Jerusalem, but it might be a gifted forger’s attempt to supply such an amulet.

Dionysus was symbolized as both a snake and a phallus.

186

Sometimes it is far from clear what the

cysta mystica

(“the mystical chest”) contained. What was inside? Did it include a snake or a phallus? Were both symbols conflated?

187

On coins the

cysta mystica

often appears with one or more snakes.

188

Generally, but not always, the Greeks and Romans considered the snake, among other things, a phallic symbol.

189

According to Clement of Alexandria, as quoted by Eusebius in his

Preparation for the Gospel

, the “mystic chests” contained not “holy things,” but various common items such as a “sesame-cake, and pyramids, and balls, and flat cakes full of knobs, and lumps of salt.” What else was in the box? It included “a serpent also, mystic symbol of Dionysus Bassarus.”

190

Post-second-century Christians, like Clement, were offended by serpent symbolism: “The mysteries of the serpent are a kind of fraud devoutly observed by men who, with spurious piety, promote their abominable initiations and profane orgiastic rites.”

191

With an awareness of Clement’s own disdain for serpents, we should read his report about the bacchanals with some skepticism. Clement reported that they

hold their orgies in honour of the frenzied Dionysus, celebrating their sacred frenzy by the eating of raw flesh, and go through the distribution of the parts of butchered victims, crowned with snakes, shrieking out the name of that Eva by whom error came into the world. The symbol of the Bacchic orgies is a consecrated serpent. Moreover, according to the strict interpretation of the Hebrew term, the name Hevia, aspirated, signifies a female serpent.

192

There may be some historical truth in Clement’s account, but he is striving to denigrate the worship of Dionysus.

No one should doubt that the serpent was used to symbolize illicit sex. We should recall the iconography of the Greek and Roman erotic gods whose phallus was upraised and sometimes resembled a serpent.

193

For example, Bes is frequently shown ithyphallically, and sometimes his exaggerated protrusion is a snake.

Numerous gods or heroes were also believed to be Ophiogenae; that is, they were born from mothers who had been impregnated by a god that had appeared to them as a serpent in a dream or often as beings in the temple of Apollo. Thus, the ancients linked the birth of great men with a serpent. Such luminaries were Aristomenes, Alexander the Great, Aratos of Sikyon, Scipio Africanus, Caesar Augustus, the twins Commodus and Antoninus, Alexander Severus, and Galerius.

194

Was Jesus’ birth celebrated in myth only by a virgin birth, as many of these other “Great Men,” to use a sociological term, or was Mary also visited by an Agathadaimon? An apocryphal story recorded in Aelian’s

De natura animalium

, seems to indicate that the Jewish girl visited by a serpent during the time of King Herod was none other than Mary, the mother of Jesus.

195

A singularly important passage for comprehending serpent symbology and procreation appears in another section of Aelian’s

De natura anima-lium

. Halia, the daughter of Sybaris, entered a sacred grove of Artemis in Phrygia.

196

A “divine serpent” ( ,

,

draco quidam sacer)

appeared to her; he was of “immense size.” He lay ,

,

et cum ea coivit)

with the young girl, “and from this union sprang the

Ophiogenis

[snake-born ] of the first generation” (12.39). While different interpretations seem possible, it is not clear what the symbolic meaning is of the two serpents tied around the waist with upraised heads on a god, dated to 580

] of the first generation” (12.39). While different interpretations seem possible, it is not clear what the symbolic meaning is of the two serpents tied around the waist with upraised heads on a god, dated to 580

BCE

, in the Temple of Artemis at Korfu.

197

The faience Minoan serpent goddesses or priestesses symbolized many things desired by human; we have suggested fertility and the need to protect the earth from destructive earthquakes. Their ample hips, small waists, and full exposed breasts indicate they also connoted good sex and fertility (see

Fig. 28

). The stunning artwork showing Aphrodite with a serpent on her thigh, found on Mount Carmel, clearly signifies good sex, power, and fertility (

Fig. 23

). The same interpretation applies to the Aphrodite with a serpent curled around her right arm; the figure found at Agrigento dates from the second or first century

BCE

.

198

The symbol of Diana or Artemis as a deer with a serpent around its neck brings to mind many positive perspectives. Perhaps the snake and the deer symbolized the fertility of the earth for humans.

In Peru, scholars have been impressed with figures having human and serpent features. They date from approximately 200

BCE

to 700

CE

and convey ideas preserved in sixteenth-and seventeenth-century Spanish lexicons that are still evident today. According to A. M. Hocquenghem, these images embody symbolically immortal power.

199

In 1999, in the Museum of Ethnology at Rotterdam, the Netherlands, African art was featured. One modern work was striking. It depicted a woman with a pink serpent, with two large eyes, placed on her chest.

Fruitfulness

The snake digs in a garden and aerates and irrigates it. The snake also kills rodents that destroy vegetation (cf. 2.26). The serpent, consequently, may symbolize fruitfulness. Sometimes this symbolism is also related to the phallus and fertility.

200

Kuster’s chapter on the fruitfulness of the serpent is divided into sections, with the serpent symbolizing the fruitfulness of: (1) vegetables and (2) animals.

201

He grounded his thoughts, typically, on the central theme of the serpent’s chthonic character; from this basic concept comes the most important symbolic meaning of ophidian symbolism: the serpent’s fruitfulness. Along with the Earth-Mother goddesses, the serpent provides for the fruitfulness of trees and also for the fertility of animals (including humans). That symbology makes eminent sense in light of the conceptual link between the serpent and the tree with its fruit, not only in the Hesperides but also in Eden. The serpent is often depicted as part of the tree or wrapped closely around it. Both the tree and the serpent are chthonic; they are ones who can delve deep into the earth. The relation between serpent and tree is evident from earliest times and can be seen most likely on Late Bronze pottery from Betula.

202