The Good and Evil Serpent (60 page)

Read The Good and Evil Serpent Online

Authors: James H. Charlesworth

Not only in the ancient world but also in modernity, snakes symbolize magic. The Australian shaman can claim that a snake is his

Budjan

(friend who supplies any necessary magic). Citing Hunt’s

Drolls and Romances of the West of England

, Halliday reported that, within the past two hundred years, a Cornish magician was seen to appear as a large black snake.

331

According to the authors and compilers of the Hebrew Bible (Old Testament), Moses’ ability to change a staff into a snake is saluted as the presence and support of the only God. It is an example, however, of magic. Moses’ use of the staff that he turned into a snake was a potent symbol because the snake was imagined to possess magical powers. This aspect of Moses’ skills is highlighted in the Qur’an. Note the passage in “Poets”: “So he (Moses) cast his staff down and imagine, it was clearly a snake! He pulled out his hand [from his shirtfront], and imagine, it was white to the spectators! He (Pharaoh) told the councilmen around him: ‘This is some clever magician who wanted to drive you out of your land through his magic’ “ (26.32).

332

In Hebrew, denotes not only snake

denotes not only snake [with accent on the ultimate syllable]) but also “divination” or “magic curse”

[with accent on the ultimate syllable]) but also “divination” or “magic curse”

(nahal

[with accent on the first syllable]). The latter provides the meaning of

nhl

in Syriac; that is, means

means

augury

, or “divination.” While it is conceivable that the two meanings are related etymologically in Hebrew, some, maybe many, Hebrews, Israelites, and Jews imagined the “serpent” to be related to divination. Evidence of ophiomancy, divination through serpents, continued from the ancient world through to the medieval world, and is prevalent today in India and Africa.

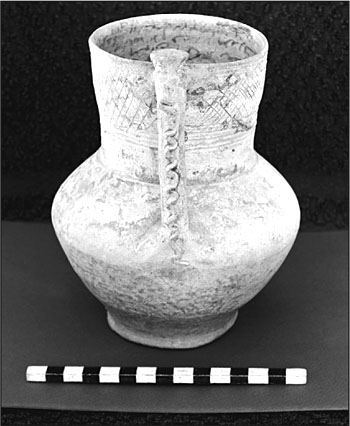

Figure 72

. Aramaic Incantation Bowl with Serpent on the Handle. Circa 600 ce. JHC Collection

Mystery, Wonder, and Awe

The unfathomable mechanisms of snakes, their ecological diversity and fascinating evolutionary process, their ability to retain feces (sometimes fecal matter can constitute 20 percent of a snake’s weight), their skill in remaining inert 95 percent of their lives, and their ability to remain in or return to one home, cumulatively have elevated the snake so that it is mysterious, wondrous, and awesome to humans.

333

The quiet and swift movement of the snake and its elusiveness caused it to become a symbol of mystery, wonder, and awe (cf. 2.6). The snake’s disturbing independence enabled it to symbolize mystery and wonder (cf. 2.11). The snake’s grandeur and majestic beauty and size (cf. 2.28) helped to support the ability of the serpent to symbolize awe.

334

In his

Histoires de serpents dans I’Egypte ancienne et moderne

, Keimer includes an insightful study of snake charmers. Most interesting is his study of serpents on ancient Egyptian monuments. According to some ancient authors (viz. Diadorus Siculus and Pliny the Elder) and ancient drawings, snakes were once imagined to be longer than full-grown elephants.

335

The uraeus, “the one who rises” according to hieroglyphics

(I’r-t)

, appears today when a cobra rises before his charmer. The Arabic noun for cobra is

ndsir

, “the one which unfolds (or spreads out).” References to a snake charmer are ancient; they appear in Sumerian literature.

336

In the distant past, before human recorded history, marvelous and mysterious creatures lived on this earth, according to ancient lore. Only two examples must now suffice to illustrate the wonder and mystery associated with snakes or serpents.

First, according to the Middle Kingdom Egyptian tale

The Shipwrecked Sailor

, an attendant to an official tells about a mysterious island that can disappear. The sailor relates how on this island he met a snake 30 cubits (about 16 m) long whose body is overlaid with gold and whose eyebrows are of “real lapis lazuli.” This snake has awesome powers and can foresee the future. He is “the lord of Punt” and “the lord of the island.”

337

Second, a certain Babylonian named Berossus sometime before the second century

sometime before the second century

BCE

, because Alexander Polyhistor cites him, composed a history of Babylonia. In his work, Berossus referred to the primordial time “in which there was nothing but darkness and an abyss of waters” (cf. Gen 1). Then, Berossus adds, “mysterious animals … BauLtaata]”

… BauLtaata]”

338

like the snake appeared, mixing in their own forms the shapes of other animals.

339

The Dionysiac mysteries cherished a

cysta mys-tica;

that is, a box in which most likely a snake was kept. The snake was perceived, sometimes, to be Dionysus himself. As H. Leisegang pointed out, the serpent symbolized mystery to the Greeks.

340

The author (or compiler) of Proverbs counts four things that are “too wonderful” for him so that he cannot understand them. The second listed is “the way of a serpent on a rock” (Prov 30:19). As Halliday stated: “[The] snake has everywhere been an object of awe and reverence. The deadliness of the snake’s bite and its uncanny appearance have marked it out for fearful adoration.”

on a rock” (Prov 30:19). As Halliday stated: “[The] snake has everywhere been an object of awe and reverence. The deadliness of the snake’s bite and its uncanny appearance have marked it out for fearful adoration.”

341

Thus, the serpent instills awe in many; he or she is the one filled with awe, and perhaps awful, whether one uses the category of the “Holy” with Otto, the “Powerful Awful” of Lang, or the “Zauberkraft” of Preuss. From ancient times until today the serpent symbolizes the awe-filled presence of “Le sacré.”

Wisdom

The snake can descend into the bowels of the earth and learn the origins of plants and life (cf. 2.24); thus, the serpent can symbolize wisdom. The snake has no ears; its silence probably leads to speculations that it is attuned to the wisdom of the spiritual world (cf. 2.2). The snake also has no eyelids and cannot stop staring; this open-eyed quality of the snake gives grounds for reflections on how it represents wisdom, which is often associated with the eye.

342

W. Foerster rightly points to the “distinctive and often hypnotic stare” of the snake.

343

I recall this look in the eyes of the cobra that rose up before me when I was on my knees photographing it in Marrakech. As pointed out repeatedly, the eye is the one feature that appears most prominent in ancient ophidian iconography. The eye symbolized the wisdom of the serpent.

344

There is a proverb in Arabic: “He is more sharp-sighted than a serpent.”

345

In Utrecht, the Netherlands, an antiquarian bookseller has given the name “Cobra” to his store.

346

Why? It cannot be that he wants something devilish to be associated with his name; he is most likely thinking about the serpent as the symbol of wisdom. Beginning in the early second century

CE

, the Ophites imagined that the serpent embodied divine wisdom (see

Appendix IV

).

347