The Good and Evil Serpent (134 page)

Read The Good and Evil Serpent Online

Authors: James H. Charlesworth

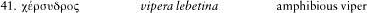

The noun is not known to the compilers of the Greek lexicons. It seems to derive from a poisonous snake that inhabits desert land (

is not known to the compilers of the Greek lexicons. It seems to derive from a poisonous snake that inhabits desert land ( denotes “arid land”).

denotes “arid land”).

70

The Greek noun is not cited by Lampe, and thus it appears not to be used by the ancient scholars of the Church who wrote in Greek.

In his

Theriaca

(359), Nicander seems to use the Greek noun to indicate some generic amphibious snake.

71

Again, some type of poisonous water snake is indicated for since it bears the Greek word for “water.”

since it bears the Greek word for “water.”

I have erred in the direction of being conservative regarding the English equivalents. Thus, I have not sought to identify the Greek names with English nouns not found in the list, such as black mamba, Boomslang, garden snake, coral snake, copperhead, moccasin, rattlesnake, black indigo, and others. Most of these names did not appear in ancient Mediterranean culture. Translators of ancient Greek documents, including the Classics as well as the Septuagint and the Greek New Testament, have too often misrepresented the sophistication of the ancient Greeks simply by equating the forty-one Greek nouns with generic terms as “snake” or “serpent,” and occasionally “viper” or “cobra.”

Etymological research provides two insights. First, many nouns derive from the habits, effect on humans, or frequent location of a snake. Second, the ancients knew the phenomenal world of nature intimately. They lived in, among, and often with snakes; they frequently adored, even worshipped, serpents. We have lost not only the ancients’ language of symbolism (symbology), but also their experience of the beauty and friendliness of nature. Translations and interpretations of such passages as John 3:14 have been marred and corrupted by the unexamined presupposition that serpents are snakes that are to be hated. Many biblical scholars tell me they despise snakes, yet this presupposition distorts the positive symbolism of a serpent found among many in antiquity; for example, Jesus, representing an aspect of Jewish Wisdom literature, advised the Twelve, when he commissioned and sent them into the world, to be “wise as serpents” ( in Mt 10:16; see also

in Mt 10:16; see also

The Gospel of Thomas

39 and the

Teaching of Silvanus

).

This initial list, especially the guesses as to proper English equivalents, will need to be improved by others, especially ophiologists and experts on ancient snakes, so that the uses of “unknown” or suggestions followed by a question mark may be replaced with a better guess. It is clearly amazing how many words the Greeks had for the serpent (the same applies to English). Studies based on the Egyptian book on poisons, the Brooklyn Egyptian Serpent Papyrus,

72

which informed Leitz when he wrote

Die Schlangennamen in den ägyptischen und griechischen Giftbüchern

, have greatly increased our knowledge of Greek and Egyptian ophiolatry.

73

On the basis of the information found in these publications and a minute study of lexicons and of ancient texts, it was possible to compile the first list of ancient Greek words for the various types of snakes or mythological dragon-serpents. Such research was fundamental for me as I wrote the previous chapters.

Although there may be forty-one nouns in ancient Greek to denote various types of snakes, only five appear in the Greek New Testament.

74

This figure, 5/41, should not seem surprising because the documents in the New Testament are theological works and should not to be confused with zoological treatises such as a

Historia Animalium

or a

De Natura Animalium

. Moreover, the Greek chosen as a vehicle by the New Testament authors was targeted for the masses; it was not intended to educate the intellectual in an academy. This perception is not diminished by the fact that many New Testament authors knew and did occasionally use sophisticated Greek (e.g. Lk 1:1–4, Rom, and Heb; contrast Rev, whose author thought in Aramaic and Hebrew but wrote in Greek).

The five Greek nouns for snake or serpent that appear in the New Testament corpus are (Rom 3:13),

(Rom 3:13), (Rev 12:3, 4, 7 [bis], 9, 13, 16, 17; 13:2, 4, 11; 16:13; 20:2),

(Rev 12:3, 4, 7 [bis], 9, 13, 16, 17; 13:2, 4, 11; 16:13; 20:2),

75 (Acts 10:12; 11:6; Rom 1:23; Jas 3:7),

(Acts 10:12; 11:6; Rom 1:23; Jas 3:7), (Mt 3:7; 12:34; 23:33; Lk 3:7; Acts 28:3),

(Mt 3:7; 12:34; 23:33; Lk 3:7; Acts 28:3),

76

and (fifteen times in the New Testament [including Mk 16:18]).

(fifteen times in the New Testament [including Mk 16:18]).

77

This lexicographical study reveals the richness of ancient Greek, and the interest of the Greeks in Egypt from which much of Greek ophidian iconography derives. It also discloses the penchant of the author of Revelation for .

.