The Good and Evil Serpent (65 page)

Read The Good and Evil Serpent Online

Authors: James H. Charlesworth

No serpents appear on Jewish ossuaries (stone containers for the bones of the deceased); images on these ossuaries eventually lost the symbolic meaning given to them by Greeks and Romans.

438

The Medea sarcophagi—the depictions of Medea in a chariot pulled by winged snakes—originally symbolized that the serpents pulling her chariot knew the way to the abode of the deceased.

439

As stated many times before, we living today have lost the naïveté of the ancients and their feeling for symbolic language. How many of us still think about the symbolic meaning of the caduceus on our medical prescriptions?

Long ago, A. D. Nock made a comment about serpents, symbols, and decoration that deserves highlighting:

A serpent can evoke a variety of associations—death, the renewal of life (as suggested by its sloughing its skin), the protective Hausschlange, the healing power of Asclepius, fecundity, a hostile power to be crushed etc. When however a Greek gem of the late sixth century B.C. shows a snake rising behind Nike, need it carry any meaning? Is it not a fallacy to suppose that what an artist produces must involve or repeat something which could be put into words? The world of forms has a certain autonomy, smaller if you will than of the world of music, but undeniable.

440

Riches and Wealth

The natural beauty of the snake (cf. 2.9) and its grandeur (cf. 2.28) helped stimulate thoughts about the serpent as a symbol of riches and wealth. The rich decorations in the tomb of Tutankhamen, for example, used the serpent to symbolize many things, including riches and wealth. The image of the serpent was used for games in ancient Egypt, and it sometimes lost its complex symbolism, degenerating into denoting the playful search for wealth.

441

In West Africa, a heavenly serpent is worshipped. This rainbow serpent offers riches and wealth to its devotees. Sometimes it is perceived to be a python that promises the best weather, fertile crops, and abundant cattle. On the Bass River, a python is revered as the great warrior who promises, among other gifts, riches. Something similar is found in the Voodoo serpent cult in Haiti.

442

These reflections clarify why ophiophilism, the love of snakes, has continued among humans for millennia. We humans once needed snakes for protection, even companionship. Those who fear them are usually those who are far removed from nature. I still marvel at the professor’s wife in South Africa who told me, without emotion, how she had been forced to kill a mother cobra and her hatch when she cleaned up her backyard. I know Americans and Europeans who have not shared her experience feel that her actions are exceedingly foreign.

The snake has been erased from our perception. This costly reduction occurred by the fourth century

CE

. Prior to the first century

CE

, the snake was one of the animals most represented in mosaics,

443

but the relegation and pejorative treatment of the snake are reflected in later mosaics. The pagan mosaics of Orpheus include the snake, but the Christian mosaics of Orpheus delete it.

444

For example, in the extraordinarily decorated late third-or early fourth-century mosaic floor at Lod, Israel, the artist depicts numerous animals, notably a lion, rabbit, giraffe, elephant, and dolphins, bulls, birds, deer, and fish, but he does not celebrate the snake. If anguine symbolism is clear in the Lod mosaic, it is a snake biting a stag or a mythological dragon between two lions.

445

The appreciation of the serpent, as in the Asclepian cult, has not influenced the artist or the owner of the villa.

Figure 76

. Bronze Serpent Bracelet, Lead Inkwell. Herodian Period. Jerusalem. JHC Collection

Summary

Why have snakes provided such various and diverse symbolic meanings? Clearly, the multivalence of serpent symbolism results from the fact that humans have experienced and expressed the most varied emotional reactions to this animal. From sometime about 40,000

BCE

to the present we have amassed evidence that humans consistently fear and revere snakes. Why?

We fear snakes primarily because they can inflict death, spewing or injecting venom that attacks the blood and heart or the nervous system. The venom is lethal and has killed humans. We also fear these animals because it is impossible to control or communicate with them, let alone tame them. We abhor snakes because they can appear without warning in our homes. Finally, reflecting on past encounters with snakes and imagining future confrontations with them provide us no paradigm for avoiding being inadvertently controlled by them.

Having articulated what seems so obvious, even to those who have not and will not encounter snakes, can anything be said on why

Homo sapiens

have for forty-three millennia admired, even worshipped, snakes? Without striving to order the reasons why humans have found snakes symbolical of positive concepts (any such ordering would misrepresent the varieties of cultures and times to be covered), I can list no fewer than fifteen reasons why the snake was chosen as a positive symbol:

- Snakes can rejuvenate themselves, appearing with new skin at least once a year, seemingly to live for ever.

446 - They never appear tired, sick, or old.

- They are astonishingly beautiful.

- Their bodies are smooth and glisten.

- They never give off a smell.

- They do not need washing or cleansing.

- They (in contrast to humans) seldom defecate, never urinate, and relatively do not pollute the air (like dogs).

447 - They may have a rare tick or other parasite, but they are not bearers of pestilence or vermin (like mice).

- They protect us from rats and other pests.

- They can go deep into the earth or the sea but we cannot follow.

- They aerate and enrich our gardens.

- They provide venom for healings.

- They are admirably independent of us.

- They taste good.

- They provide attractive skins for accessories and shoes.

At this point, some attentive readers might object, claiming that more should be added to the list of negative characteristics of snakes. They might contend that snakes are slimy and clammy and awful to touch. They would perhaps argue that snakes are aggressive, seeking by their nature to attack and kill humans. They probably would claim that snakes are filthy since they spend their lives in the filth of the earth.

What can we reply to these claims? Are they not patently accurate?

These claims do accurately reflect the fears of many, but they derive from mythology and not fact. Children who have not been taught to fear snakes find that when they hold a garden snake or a black indigo, they admit that the feeling is attractive and comfortable. Ophiologists have proved, from years of study and experimentation, that snakes are not aggressive; by nature they are defensive. Snakes do not seek to kill humans; in fact, when threatened they often release only a minor amount of venom (snakes can control the amount of venom excreted). If snakes come into the home from the sewer, they are filthy and dangerous as we would be if we had been in a sewer. The Ophites would never have imagined a serpent could consecrate the bread for the Eucharist if it were in any way perceived to be a bearer of pollution or filth.

Gifted symbologists and phenomenologists will now feel that the main issue has become distorted. They will point out that even though it has been proved that ophidian iconography and symbology derive from the physiological characteristics of snakes, a major point has been lost. They will stress—and rightly so—that it is not the physical characteristics of snakes that undergird ophidian symbolism, it is the human perception of these characteristics.

No one should deny that perception helps create symbols. Yet perception precedes symbolism. Our perception of snakes defines and allows for ophidian symbolism. We never see snakes sick or old; we see them rejuvenated periodically. That stimulates reflections on immortality (which eludes us as well as snakes). We sometimes cannot discern which end of a snake is a tail or a head, which is especially unclear in some earthworms or small snakes. Our perceptions of beginning and end—the continuum of philosophical reflections—are deepened when we see a snake’s head protruding from another snake’s mouth or a snake’s tail close to or in its own mouth (Ouroboros). How did time begin and what is time and eternity? Ophidian iconography helps us broach and represent such perennial questions.

Around humans the heads of snakes are almost always raised and alert. The upraised snake is a fact of nature (

Figs. 13

and

15

) and of serpent iconography (e.g.,

Figs. 42

and

49

). The upraised serpent provides the symbol-ogy we see in the uraeus, as well as in Numbers 21 and John 3. Thus, as we proceed, we should keep in mind the recognition that behind ophidian symbology lies the fascination of humans with snakes, the physiology of snakes, and most notably the perception of the phenomenology of snakes.

Now we may return, with deeper insight, to the fifteen reasons why humans have found snakes to be attractive and desirable. These reflections help us imagine the millennia when our ancestors lived in caves, with snakes, and the millennia others worked in the fields or sat in huts or houses in which a snake was welcome. The almost global penchant of frantically killing snakes, especially in Ireland and the United States, has changed the world that had been created. We also have become divorced from the earth and from nature. The words “Mother Earth” have disappeared from our lexicons. They no longer bring comfort to our lips.

CONCLUSION

Paul Tillich argued that a symbol obtains some of the meaning of what it points to, but a sign only points to something else. He influenced such luminaries as Reinhold Niebuhr, Paul Ricoeur, Langdon Gilkey, and David Tracy. We have seen that serpent images were not only signs; they were symbols that made present the ideas and concepts imagined. We have seen reasons to agree with C. G. Jung that serpent symbols appear in all human cultures, suggesting a shared archetypal collective unconscious in humans. I would agree with Ernst Cassirer that humans are distinct from other animals by their ability to create symbols.

Serpents symbolize neither something bad nor something good. They even provide more than just symbolically portraying both these opposites together (double entendre). Biblical scholars and experts in other fields of antiquity should grasp more fully a fact seldom perceived today but articulated in 1850 by F. G. Welcker: of all animals, the serpent has provided the richest and most complex meanings to the human.

448

Because of the extraordinary physiological and habitual characteristics of these creatures, and their complex, contradictory relations with us humans over time and at the same time, they have become a symbol that reveals the vague, often contradictory, boundaries of the language of symbolism.

449

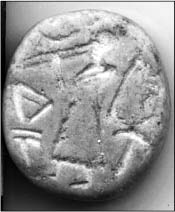

Figure 77

. A Scarab Found in or Near Jerusalem. A man with a flute and an upraised cobra behind him. Circa eighth century BCE. J HC Collection

We must be careful not to overinterpret symbols. As music cannot be said and poetry only misrepresented by prose, so symbols must not be equated with what are articulated concerning them. They have a language of their own. Their abilities to evoke thoughts and emotions cannot be reduced to words. Symbols do not display, not even when they are voluptuous serpent goddesses; they point to that which the human yearns for and needs for sustenance, survival, and—most of all—meaning in a phenomenologically chaotic world. It would not be in our own best interest to reduce the ophidian object in

Fig. 77

to a limited number of meanings. The importance of this illustration may be in its power to evoke and instill wonder. Why is a man playing a flute with an upraised cobra

behind him?