The Good and Evil Serpent (64 page)

Read The Good and Evil Serpent Online

Authors: James H. Charlesworth

In “Serpent Imagery in Ancient Israel,” Le Grande Davies astutely suggests that an “examination of the contexts of

seraph

indicates its ‘burning’ aspects are related to cleansing, purifying or refining of objects, people, cities, etc.” (p. 83). The clearest example of the relation between the Seraphim and purification is not grounded in the verb. Isaiah laments that he is impure: “A man of unclean lips I am; and in the midst of a people of unclean lips I dwell” (Isa 6:5). How is this great prophet cleansed? One of the Seraphim—winged serpents (see

Appendix I

)—takes a hot coal from the altar and touches his mouth. The divine burning-serpent declares:

Behold, this has touched your lips;

Your iniquity is taken away,

And your sin purified. [Isa 6:7]

In Greek and Roman myth and folklore, the lick of the serpent is purifying and imparts unusual abilities. For example, snakes purified the ears of Melampus. On awakening, he could understand bird language and became a prophet.

417

Likewise, serpents licked the ears of Cassandra and Helenus, in the sanctuary of Apollo. So purified, they also were able to understand the language of birds.

418

In our attempt to organize and categorize the symbolic meanings of the serpent, some reflections by Ambrose might be placed here. In his

Of the Christian Faith

, Ambrose urges his fellow Christians to be like serpents. Note his exhortation:

For those are serpents, such as the Gospel intends, who put off old habits, in order to put on new manners: “Putting off the old man, together with his acts, and putting on the new man, made in the image of Him Who created him.” Let us learn then, the ways of those whom the Gospel calls the serpents, throwing off the slough of the old man, that so, like serpents, we may know how to preserve our life and beware of fraud.

419

Transcendence

The snake does not show emotion, fear, or pain (cf. 2.3, 2.15, 2.21), is fiercely independent (cf. 2.11), and can transcend the limitations of other creatures (cf. 2.17). These physiological and habitual characteristics of snakes helped stimulate the perception that the serpent symbolized transcendence.

In

Man and His Symbols

, C. G. Jung stressed the ability of the serpent to symbolize transcendence. Jung published the following conclusion: “Perhaps the commonest dream symbol of transcendence is the snake, as represented by the therapeutic symbol of the Roman god of medicine Aesculapius, which has survived to modern times as a sign of the medical profession.”

420

J. L. Henderson and M. Oakes point to the serpent as the symbol of transcendence. Especially noteworthy are the ways Hermes acquired wings and symbolized spiritual transcendence. The authors focused on the entwined serpents, the caduceus and the Indian Naga serpents; they explained this serpent iconography as an “important and widespread symbol of chthonic transcendence.”

421

It does seem clear that when Hermes becomes Mercury, he obtains wings. He became “the flying man” and possessed the winged hat, sandals, and even a dog as companion. Henderson and Oakes appear to be right in interpreting the iconography of Hermes: “Here we see his full power of transcendence, whereby the lower transcendence from underworld snake-consciousness, passing through the medium of earthly reality, finally attains transcendence to superhuman or transpersonal reality in its winged flight.”

422

Rejuvenation

Because the snake sheds its skin (ecdysis) and regains a youthful appearance (cf. 2.17), it came to symbolize rejuvenation. Without wrinkles and with no signs of old age, the serpent, through ecdysis, was imagined to symbolize youthfulness and rejuvenation. In the Asclepian cult, the serpent symbolized new life and health. Nicander preserves an old myth in which humans did receive the gift of youthfulness, but, being lazy, they let an ass carry the gift. The ass bucked and eventually sought a snake to quench his thirst. The serpent was pleased to bear the burden on the back of the ass because he then obtained eternal youthfulness or rejuvena-tion.

423

Once again, as in the Gilgamesh epic, the serpent wins the prize sought by humans. Of all creatures, the serpent symbolized the one who had the secret of rejuvenation.

Immortality, Reincarnation, and Resurrection

The Greeks and Romans knew that immortality without youthfulness would be a curse.

424

The lover of the goddess Dawn—who appears fresh and resplendent each morning—obtained immortality. There is an ironic twist; he continued living but he simply grew older each day

(Homeric Hymn

5.218–38). Endymion receives eternal youth from Zeus, but he cannot sleep (Apollodorus 1.7.5). Juturna receives immortality from Zeus, but must witness the death of loved ones

(Aeneid

12.869–86).

Because the snake sheds its skin and apparently obtains new life (cf. 2.17), it became the quintessential symbol of immortality and reincarnation. Among the Jews and Christians who held a belief in resurrection, sometimes the serpent represented that belief.

This point, at least for Sumerian culture, was clarified and emphasized by V. Lloyd-Russell in his 1938 PhD dissertation at the University of Southern California. It is entitled “The Serpent as the Prime Symbol of Immortality Has Its Origin in the Semitic-Sumerian Culture.” His dissertation, while interesting and informative, is undermined by the claim that the cradle of serpent symbolism must be in or near Sumer or Akkad and from “this homeland, the symbol followed the great migrations of people from the Old World to the New” (p. iii). While Küster sought to subsume all serpent symbology under the concept of the chthonic, Lloyd-Russell sought to prove that the primary and dynamic meaning of serpent symbolism is always immortality.

425

The result is the degeneration of an interrogative thesis into an attempted demonstration of an idea. We have seen that serpent symbolism does not suggest one originative locale; it is an aspect of the commonality of the human who lives in and near snakes and perceives something important for meaningful life. Without doubt, the human aspires to escape death and has often employed serpent symbolism to articulate this common, but elusive, dream.

The snake (like some other animals, especially the lizard) sheds its skin. When one walks in the wilderness or any place where snakes dwell, one often sees the sign of death: discarded snakeskin. But the reflective person readily knows that there is a live snake not far away. This rather “unique” habit of the snake influenced religious symbolism. In the world’s religions, the serpent symbolized rebirth, reincarnation, and even (later) resurrection, because the snake leaves its old skin (it only apparently dies) and moves into what looks like a new body. The Phoenicians celebrated the rebirth, perhaps resurrection, of Adonis and chanted something analogous to

resurrexit dominus:

“The lord is resurrected.”

426

Since the snake appears to die and live again, the waxing and waning moon is often depicted symbolically as a serpent.

427

This concept may help explain why in the Congo the Nagala believe that the moon was formerly a python on earth.

When the snake is depicted coiled, it may symbolize immortality.

428

The “Coiled One”

(mhn)

game, with the serpent in a coil, in the Pyramid and Coffin texts was a means of transformation to rebirth and even ascension into heaven.

429

The serpent represented eternal life. As V. Lloyd-Russell stated: “It is not paradox that the reptile, whose venom caused the annihilation of the life of man, should be chosen to articulate eternal life. He might destroy but he contained life. If he were propitiated, if one could ingratiate oneself before him, the eternal Sa might even be communicated in the bite.”

430

In antiquity, the Gilgamesh epic, “the most famous literary relic of ancient Mesopotamia,”

431

which influenced some traditions in the Old Testament, solidified in writing the legend that the serpent alone possessed the plant of immortal life. W. F. Albright called the Gilgamesh epic “that remarkable work of early Babylonian genius … which attains its culmination in the hero’s vain quest of eternal life.”

432

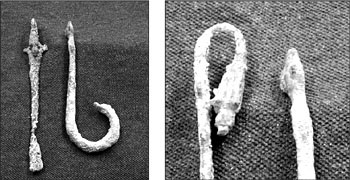

Figure 75

. Bronze Stirrers. From Jerusalem

(left)

and Jericho

(right);

both are early Roman, probably Herodian Period. Note each serpent head. JHC Collection

In Egypt, the serpent is connected with some form of immortality or “resurrection.” In the Pyramid Texts, the dead king is awakened and his odor is like that of a special serpent; he does not rot

(Utterance

576).

Utterance

683 has the following: “It is Horus, who comes forth from the Nile … it is the d.t-serpent which comes from Rë

c

; it is the

5

i

c

r-t-serpent which comes from Set.”

433

In numerous Greek legends, especially concerning Glaucus and Tylon, serpents are depicted as those that can bring back the dead to life. Hercules leaves the snake in the tree in the Garden of the Hesperides and makes off with the golden apples of immortality (see

Fig. 56

). S. Reinach pointed out that at the heart of Orphism is the birth, death, and resurrection of Za-greus, who appears iconographically as a serpent with a small crown.

434

The serpent can symbolize many ideas and concepts; some are negative and others positive. Among the latter are images of the serpent that reveal its symbolic power to represent rejuvenation, immortality, reincarnation, and resurrection.

Purely Decorative

On those occasions when human beings view the snake as attractive (cf. 2.19), they choose serpent images to exemplify that beauty. In this study, our focus has been on serpent symbolism. Hence, sometimes a drawing of a serpent or a golden serpent bracelet may merely be intended either for decoration or to enhance someone’s attractiveness. Symbolism thus ceases and the symbol no longer has meaning; when the symbol is seen only as embellishment, symbolism ceases.

Images that had been richly symbolical can become merely decorative or aesthetic. In the

Dictionnaire d’archéologie chrétienne et de liturgie

H. Leclercq rightly stated that sometimes “the serpent appears simply to fulfill a decorative role.”

435

While I disagree with him that a serpent on a sarcophagus is mere decoration (it probably signals a belief and hope in some new and better life after death), some lintels and jewelry may have been designed or intended only to appear attractive and decorative.

While I am persuaded that originally, at least, most of the serpent imagery had deep and complex symbolic meanings, many intellectuals, especially in the middle and later Roman periods, would have thought an anguine object was merely ornamental. The Roman bronze ladle for dipping wine mixed with water may have connoted for some guests many positive feelings, but other guests probably took them only as attractive decoration (see

Fig. 63

). Serpents on vases (

Fig. 61

), and the numerous bronze, silver, and gold serpent bracelets, rings, and earrings certainly connoted positive symbolic meanings, but for many they were mere jewelry (see

Figs. 34

,

35

,

38

,

39

,

40

,

41

,

62

). Elegantly made glass objects with serpent appliqué denote many symbols, but they were also ornamental (

Fig. 71

).

436

The silver Viking serpent ring probably had mythological meanings, but it was also attractive, and the bearer may have worn it only for decoration (

Fig. 9

). The Minoan serpent goddesses or priestess (

Fig. 28

) and the Carmel Aphrodite with a serpent on her thigh (

Fig. 23

) symbolized many attributes, but some who viewed them may have had no symbolic imagination and took them as only artworks of magnetic attraction. The tattoos of snakes in ancient and modern Egypt, and elsewhere, may be merely for decorating the body, or they may have special meanings perhaps known only to those who wear them.

437