The Good and Evil Serpent (136 page)

Read The Good and Evil Serpent Online

Authors: James H. Charlesworth

Is it not more likely that the painting of Priapus mirrors the fascination of Pompeians with the serpent? Would it not be unperceptive of us to imagine that only we know that male serpents have two phalli? While there is no clear link between Priapus and ophidian symbolism at Pompeii, he does appear elsewhere (like Bes) with a phallus as a serpent. Perhaps specialists in symbology have not sufficiently studied the anatomy of snakes to see analogies in art that were put there, or seen there, by the Pompeians. The link between Priapus with two phalli and the serpent may be also indicated by the fact that he is standing near a tree; in ancient art, the serpent and tree are often associated (as clarified previously).

While working in the Hermitage in St. Petersburg, I was astounded by the attractive depictions of the serpent with Hygieia. In Pompeii and in the Naples Archaeological Museum, I was impressed by the many large serpents displayed in frescoes and paintings. For example, a serpent is featured in

Bacco e Vesuvio

(No. 11986). It is Agathadaimon. He fills the lower half of the painting, rising up beneath Mount Vesuvius, which appears tranquil and with its pre-79 top.

Figure 93

.

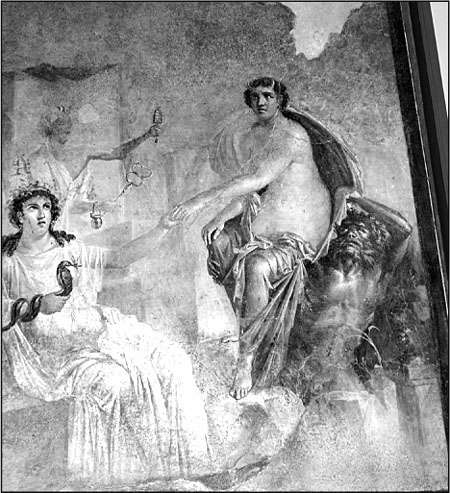

Arrivo di lo a Canopo

. Painting No. 9558. Pompeii. JHC

In

Arrivo di Io a Canopo

, found in the Temple of Isis, a woman sits serenely. In her right hand she holds an asp, who rises with hood spread and tongue projected (No. 9558).

Other serpents appear in paintings and frescoes for the visitor to the Naples Archaeological Museum (viz.

Oggetti del culto Dionisiaco

). Most of the artwork is from Pompeii. I have the impression that the serpent was the favorite animal for the Pompeians. For them, it clearly symbolized many positive concepts, ideas, and ideals. We also need to remember that living snakes were honored in homes for religious and practical reasons.

Streets. In “Vicolo Storto,” one can still see a large painting of two snakes on the external wall of a house. The place is close to a room in which prostitutes worked. Surely Professor De Simone is right to point out that there is no connection between this representation and the exercise of such women.

11

There is no relation between the wall painting and the “Brothel House;” moreover, prostitutes could not afford such a fresco. The painting represented not the imaginations of sexually skilled women; it depicted the fascination of the average Pompeian with serpents.

In Region I, insula 8, one may see another painting of a snake on an external wall. The mural is badly destroyed, but the original size of the painted serpent is evident. It is at least 5 meters long (over 15 feet).

12

The undulating body of the depicted serpent most likely symbolized, inter alia, life (Pos. 20) as well as riches and wealth (Pos. 29).

Jewelry. Working in the Medagliere e Collezioni del Museo in the Naples Archaeological Museum, I learned that virtually all the attractive jewelry found in Pompeii and Herculaneum is gold with serpent images.

13

Again, my report must be selective (see also

Chap. 3

, esp. “Archaeological Evidence of the Influence of Greco-Roman Ophidian Iconography in Ancient Palestine: The Jewelry of Pompeii and Jerusalem”).

Figure 94

. Gold Serpent Ring. No. 25040. Pompeii. JHC

No less than ten gold rings were examined in the Medagliere. Three of them are shaped so that at the ends of the open ring two serpents face each other, perhaps signifying the caduceus (11159, 25039, 25040). The most intricate and heaviest ring is No. 25040; it is 2.7 centimeters wide and 2.7 centimeters high. Tongues protrude from the serpents’ mouths. Four holes indicate the eyes; no jewels remain in the holes and perhaps none were ever placed in them.

One gold ring is heavily worn (No. 113744). Probably this ring had been worn by other women, perhaps a mother and conceivably a grandmother. The ring is heavy and well made; it is 2.4 centimeters high. The serpent has four curves.

One gold ring (No. 80) features a serpent; it also has four curves. It is 0.8 centimeters high and 2 centimeters wide. When the ring lies on a table, it looks like a coiled, upraised cobra. Ring No. 25043 has the appearance of an Ouroboros.

The gold bracelets and armlets that are fashioned as serpents are too numerous to discuss. Examining the serpents’ heads of some of these, I had the impression that jewels once had been in the holes that graphically represent the eyes of serpents. This assumption was proved by an examination of a gold bracelet (No. 126365). It is 8.4 centimeters high and 7.9 centimeters wide. The bracelet is very heavy and crafted from fine gold. It was intricately and artistically made. The serpent is realistic—its scales are represented by numerous indentations on the body.

This bracelet received minute attention from a skilled craftsman. The serpent’s head obtained special focus. It is triangular; hence, a poisonous snake like an asp was imagined by the artisan. The head is 2.4 centimeters long and 1 centimeter high. The details of the head include the smooth area of a serpent’s head and the customary prominent eyes. The circular depressions impressively indicate eyes in which jewels were set. As just intimated, one eye still retains a jewel; it is 0.3 centimeters in diameter and may be an emerald.

The serpent’s mouth is open. Under the head, indentations in the gold denote scales. There are three curls. Studying the serpent bracelet, I considered the symbolic meanings intended by the creator, those added by the wearer, and those imagined by any who beheld it. The Pompeians would have seen symbolically represented at least the following: beauty, power, strength, and especially life.

Conclusion

In the first century

CE

, Pompeii was not a cult of serpents, but the Pompeians encouraged many cults that deified and worshipped the serpent—the evidence of Egyptian culture, with its many serpent gods and goddesses, is palpable.

The veneration of the serpent existed in this part of the world for centuries. A painted krater can be seen in the Museo Archeologico di Pithecusae; it features a serpent on a shield, and dates from the fifth century

BCE

. But the profusion of serpent images at Pompeii is uncommon. This city was wonderfully situated, and all segments of the populace were united by one image: the serpent.

14

This animal signified many aspirations and hope, notably, healing, long life, renewed life, and continued life (see, respectively, Positive Symbols 23, 20, 27). Many in Pompeii would have agreed that the serpent was a very positive symbol. An inscription celebrated love with the symbol of a bee,

amantes ut apes vitam mellitam exigent

(“lovers like bees make life [sweet as] honey”). I found no inscription that mentions a serpent. Yet the bee was celebrated at Luxor, not Pompeii. In the Roman city, the serpent was the dominant symbol.

Imagining the symbolic world of the Pompeians, I may more fully comprehend that a symbol is a synthetic reality. A symbol is obviously more than a word or a picture. It has many meanings, as we saw during our study of serpent symbolism in antiquity. Symbols embody magical meanings (Pos. 16 and 17). Perhaps words are the best medium for appealing to our intelligence. If so, symbols, pictures, and images are human creations designed to evoke feelings, past experiences, and future hopes. Perhaps at Pompeii the images of serpents helped the Pompeians to imagine not only new life (Pos. 20, 26, 27) but also the continuation of the family and the household. As the many notes in Mozart’s

Don Giovanni

constitute a symphony of sound, so the many images at Pompeii create a world of symbology in which the serpent symbolizes all human dreams and aspirations.

Appendix IV: Notes on Serpent Symbolism in the Early Christian Centuries (Ophites, Justin, Irenaeus, Augustine, and the Rotas-Sator Square)

In the preceding pages, I frequently drew attention to the interest in the serpent that was shaped by an exegesis of John 3:14–15. Now, I shall organize some thoughts on the Ophites, add a select few comments by the so-called Fathers of the Church, and introduce a challenging, if speculative, meaning of the Rotas-Sator Square.

Ophites (Naasanes, Peritae)

The Ophites, a “sect” of Christians, appeared in the second century

CE

. They apparently vanished sometime in the fourth century, with the clarification of “orthodoxy” supported by the power of the “Holy Roman Empire.”

Ophites. In the treatise

Against All Heresies

, dating perhaps from the third or fourth century

CE

, an unknown writer castigated Christians who were referred to as “Ophites.” According to this writer, remembered as “Pseudo-Tertullian,” this group was so named because of their interpretation of John 3:14–15 and the exaggerated and literal interpretation of Christ as the serpent. Pseudo-Tertullian claims that the Ophites “prefer” the serpent “even to Christ himself; for it was he, they say, who gave us the origin of the knowledge of good and of evil.”

1

The writer continues to summarize the mythology of the Ophites, and contends that the Ophites believe that “Christ himself … in his gospel imitates Moses’ serpent’s sacred power, in saying: ‘And as Moses raised the serpent in the wilderness, so it is necessary for the Son of man to be raised up.’ “

2

It is singularly significant for our research to observe that John 3:14 is quoted. We should review critically, and with requisite suspicion, any polemical representation of another’s views.

In his encyclopedic refutation of the so-called heretics, Epiphanius (c. 315–403) discusses the Ophite sect. He reports:

[T]hey are called Ophites because of the serpent which they magnify. … and in their deception they glorify the serpent, as I said, as a new divinity. … But to those who recognize the truth, this doctrine is ridiculous, and so are its adherents who exalt the serpent as God. … these so-called Ophites too ascribe all knowledge to this serpent, and say that it was the beginning of knowledge for men.

3

Epiphanius is not attempting to represent or be sympathetic to this sect; he unabashedly castigates it as “stupidities” (1.1), “foolishness” (5.1), and “silly opinion” (5.2). Yet he provides valuable information on this sect with its extreme exegesis of Numbers 21 and John 3, which they cite directly, per Epiphanius (7.18.1). According to Epiphanius, they hold a myth that the supreme god: “stared down at the dung of matter, and sired a power that looked like a snake, which they also call his son” (4.4). The Ophites apparently defended their mythology by claiming that “the entrails” of all humans are “shaped like a serpent” (5.1). Building their ideology on an exegesis of Genesis 3, they magnify the serpent because “he has been the cause of knowledge for the many” (5.2). They allegedly celebrate the Eucharist by allowing a snake, which they subsequently kiss, to encircle the bread placed on the table: “But they worship an animal like this, and call what has been consecrated by its coiling around it the eucharistic element. And they offer a hymn to the Father on high—again, as they say, through the snake—and so conclude their mysteries” (5.7).

In refuting the Ophites, Epiphanius reveals that he metaphorically interprets John 3:14 to mean that

Christ is like the serpent

, after the typos of Numbers 21. He rightly claims: “[The] thing [that is the serpent] Moses held up in those times effected healing by the sight of it—not because of the nature of the snake but by the consent of God, who used the snake to make a sort of antidote for those who were bitten then” (7.1). He denigrates the Ophites because they interpret the text of John 3:14 “literally” (7.6). His interpretation demands the recognition: “Jesus Christ our Lord … is no serpent” (8.1), and his portrayal of the serpent’s symbolism is purely negative: “There is nothing wise about a snake” (8.1). Yet he perceives the metaphorical meaning of John 3:14: “And as healing came to the bitten by the lifting up of the serpent, so, because of the crucifixion of Christ, deliverance has come to our souls from the bites of sin that were left in us” (7.5). He notes that Jesus, according to Matthew, said that his followers must be “wise as serpents,” and he struggles to interpret this saying. He attempts to find something wise about the serpent, but only reveals his ignorance of it. For example, he says that the serpent is wise because it “does not bring its poison” when it leaves its den for a drink of water (8.5).