The Good and Evil Serpent (138 page)

Read The Good and Evil Serpent Online

Authors: James H. Charlesworth

The Rotas-Sator Square should not be called a “rebus”

19

since that term refers to a series of words represented by pictures or symbols. A much better description would be to call it a cryptogram or better a cryptograph; that is, something composed in a code or in a mystical pattern.

The Square Is Not Christian

The square also hides a cruciform made from the word

TENET

(the palindrome). This form is certainly no evidence that the Latin square is Christian.

20

The cruciform should not be deemed Christian prima facie. It is ancient; for example, it can be seen in Mesopotamian art that antedates the first century

CE

by millennia. It is evident in the following works of art:

a bowl from Ur (second half of the fifth millennium BCE)

a bowl from Susa (beginning of the fourth millennium BCE)

stamps and seals (fourth and third millennium BCE)

proto-dynastic seals (end of fourth millennium BCE)

cylinder seals (second millennium BCE)

21

Jews also used a form of the cross to signify various ideas; none of them is to be confused with the meaning Christians give to the “cross.” Many of these Jewish symbols that look like a cross date from near or in the first century

CE

, but we should not be confused into thinking about the development or even evolution of a cross symbol from Judaism to Christianity.

22

The attempts to read the Latin cryptogram as a Christian inscription have proved unsuccessful. Christian scholars who imagined it as designating “Pater Noster” have not been persuasive.

23

Numerous scholars, notably Moeller, Last, Fishwick, and Gunn,

24

were convinced that the Latin language makes it very difficult to arrange letters so that a five-lettered cryptograph that can be read both left to right and right to left is created. They were wrong. W. Baines draws attention to

eighty-eight possible squares

that can be created out of Latin, which he shows is “ideal for producing word-squares.”

25

I am persuaded that the Rotas-Sator Square cannot be a Christian composition because of the numerous presuppositions demanded by such a hypothesis. Yet, unfortunately, the Rotas-Sator Square is cited as a Christian creation in many handbooks and introductions to the origins of Christianity.

Here are my reasons why the square is probably not Christian: First, the cryptograph has been found in Pompeii. That means Christians must be living there before 79

CE

, and probably even before 62, which is the most likely date for the graffiti in Pompeii.

26

Second, while this assumption is not impossible, there are no supporting proofs for it,

27

and it also demands that Christians chose the cross to symbolize their religion by the early sixties, since

TENET

forms a cross. Yet we have no evidence that the cross was a Christian symbol in the first century; it most likely came into use after the first century, but before Constantine’s vision in the fourth century (he saw a cross in the sky and believed that with “this sign” you will conquer), and is apparently to be discerned in the catacombs of Lucina and Priscilla. The symbol of the cross is perhaps mentioned in the second-century

Epistle of Barnabas

(9:8), but all of these examples are too late to prove Christian use of the cross before 79.

28

Third, the cryptogram is not fully understood by “Pater Noster” since “A” and “O” are left out of the meaning. To suggest that they represent Alpha and Omega smacks of special pleading.

Fourth, the Alpha and Omega symbolism associated with Christianity is clear only in the Revelation of John,

29

which is usually dated to the nineties. That date is thirty years too late to indicate Christian composition for the Rotas-Sator Square.

Attempts to Explain the Square

Why has the meaning of the Latin mystified scholars? Far too often, scholars come to a symbol or mystical sign with preconceptions; as O. Keel pointedly proved in

Das Recht der Bilder gesehen zu werden

, all symbols have the right to be seen before they are interpreted.

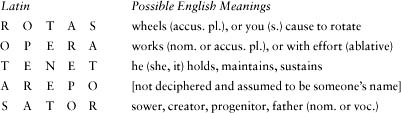

Past attempts to discern the meaning of this Latin cryptograph, which have been voluminous, allow the following possibilities:

Sator

. There is not only a square to the image, but a meaning that seems to run around it.

Sator

is written at the bottom left to right, then from the same starting point from bottom left to the top, and once again from top right in both directions, left and downward. The appropriate word with which to begin seems to be Sator. This crucial word means “sower,” “progenitor,” and especially “creator.” What is the sequence for the words?

To discern the meaning of this Latin cryptic word square we should recognize that the square is magical or mystical and, thus, the author is not referring literally to a sower who works a field. The author is probably referring to “the Creator.” Such a meaning would have been readily significant to the learned and average person in the Roman Empire. And we should assume that many, if not most, of them knew the meaning of the square.

Arepo, tenet, opera, and rotas

. The sequence of words seems to provide a sentence as follows:

SATOR AREPO TENET OPERA ROTAS

. What would that mean? The Latin

Sator … tenet opera rotas

, prima facie, would mean “The Creator … holds with effort the wheels.” The Latin word

tenet

means “to hold” or “to maintain” and it is the palindrome of the square; that is, it provides the same meaning when read right to left or left to right (as well as from top to bottom and bottom to top).

30

Arepo

. The suggested sentence, “The Creator … holds with effort the wheels,” raises two questions and a problem. Why “with effort”? And also why the plural “wheels”? A suggestion for each of these problems must await the problematic word:

arepo

. As many have pointed out, this is a word that is unknown. Most lexicographers either speculate that it is the name of some unknown person or that it is merely a meaningless series of Latin letters demanded by the opposite of its mirror image in the cryptograph,

opera.

31

The hallmark of research is not to give up with easy solutions or be content with unattractive answers. Hence, what does

arepo

denote? It looks like a verb, which means that the scholarly attempts to assume it is the name of the “sower” is simply sufficient evidence that such a hypothesis has collapsed from the weight of its own assumptions.

The Latin

arepo

could be the first-person indicative of a verb. The most likely suggestion is that it is from

arrepo

, which is also

adrepo

,

32

or

arepo

and because of phonetics one “r” has elided; that is, to say “arrepo” eventually evolves into the easier-to-pronounce “arepo.” Also, the six-letter

arrepo

would not fit into the five-lettered square, so it would be necessary to choose the truncated

arepo

. Thus, “to creep toward” is a possibility worth pursuing. A cognate verb is

r*p* (-ere, r*psi, r*ptum)

, which means “to creep” and “to crawl.” Taking

arepo

as a verb, we thus derive the meaning: “The creator, I creep toward.” The problem with this explanation is that “creator” is nominative and an accusative would be needed to clarify the object to which “I creep toward.” Perhaps the sentence means, “The creator—[to whom] I creep—holds the wheels with effort.” That is not attractive grammar, but it is possible and fits nicely with the needs of a magical square. We should not attempt to understand the Rotas-Sator Square primarily by means of refined grammar; not only does that move the common or “vulgar” cryptogram out of its sociological context, but it imposes false criteria for discerning the intent of the author.

Sator and arepo

. Who is this “creator”? Could it be Asclepius?

The key to unlocking this long too mysterious Latin word square is the word immediately following “Sator”—that is, “Creator.” The Latin word

arepo

, along with its cognate

repo

, provides us with “reptile” in English. The “Creator” to whom the devotee crawls, like a snake, may be Asclepius. This god is preeminently represented in the first century

CE

by the symbol of the serpent. Thus, “I creep toward” is to take on the symbolic meaning of the Creator, perhaps Asclepius.

It is good to select some ancient witnesses to the Asclepian cult to stress, again, the symbolic identity between serpents and Asclepius: “[S]erpents are just as much sacred to Trophonius as to Asclepius.”

33

These are the words of Pausanias who wrote in Rome near the end of the second century

CE

. Earlier in the first century

BCE

, Ovid portrayed Asclepius saying: “Only look upon this serpent

(serpentem)

which twines about my staff.”

34

Between Pausanias and Ovid, and a contemporary of the Fourth Evangelist, lived a man whose dedication to study and exploration led him to become “the martyr of nature” since his curiosity led him to Pompeii during the volcanic eruption of 79

CE

. This scholar, Pliny the Elder, reported: “[T]he Asclepian snake

[Anguis Aesculapius]

… is commonly reared even in private houses

[vulgoquepascitur et in domibus].”

35

Asclepius was revered from the West to the East of the Roman Empire in the first century

CE

, thus explaining the widespread distribution of the Latin magical cryptograph. Xenophon (c. 430-c. 354

BCE)

celebrated Asclepius and reported “he has everlasting fame among men.”

36

Significant for understanding the square, Asclepius is also called “savior.” Note these random examples:

Shall I go on to tell you how Helius took thought for the health and safety of all by begetting Asclepius to be the Savior of the whole world.

37

[Julianus, 332–63 CE]

… Asclepius, the Savior and the adversary of diseases.

38

[Aelianus, c. 200 CE]

… Savior … they called Asclepius that.

39

[Suidas, c. 950 CE]

Opera

. Why “with effort”? Asclepius, as a demigod, is an excellent fit for the inscription. As Edelstein states, Asclepius “had endured so many hardships.”

40

In fact, Porphyrius (232–304

CE)

, in his

Epistle to Marcellus

, states that Asclepius completed: “[T]he blessed road to the gods through toil and strength. For … the upward paths to god” are attained “by those who have learned nobly to endure the hardest circumstances.”

41

Rotas

. Why does the inscription have the plural

rotas

, “wheels”? Would not the singular

rota

, “wheel,” more adequately denote the wheel of the cosmos? Not necessarily, since the depictions of the zodiac often have it within two circles, or wheels.

What is the meaning of “The Creator—[to whom] I creep—holds the wheels with effort?” Aristides (129–189

CE)

salutes Asclepius as the god who: “[H]as every power.” Indeed, he is “the one who guides and rules the universe, the savior of the whole and the guardian of the immortals, or if you wish to put it in the words of a tragic poet, ‘the steerer of government.’ “

42

About the same time as the completion of the Fourth Gospel, Philo of Byblos mentioned the snake-like god who is named Ophioneus. Philo then mentions the Egyptians who portray the cosmos according to the same notion. Philo reports: “They draw an encompassing sphere, misty and fiery, and a hawk-shaped snake dividing the middle. … the circle is the cosmos, and they signify that the snake in the middle holding it together is Good Demon.”

43