The Good and Evil Serpent (29 page)

Read The Good and Evil Serpent Online

Authors: James H. Charlesworth

Summary

The amount of ophidian iconography unearthed by archaeologists is vast and astonishing; its message will be enlightening to those who assume that serpents, serpent cults, and serpent veneration were never a significant aspect of worship in “the Holy Land.” Let us summarize what has been collected and discussed in the preceding pages.

All the seven serpents discovered in ancient Palestine, and thus excluding the thirteenth-or twelfth-century gold-plated copper serpent from Timna‘, are bronze and date from the Late Bronze Age or earliest years of Iron I. The exception is the gold serpent from Ekron that dates from the seventh century

BCE

and is explained as an Egyptian importation. Why do all the serpents share this material and time; how do we explain this circumscribed floruit of individual bronze serpents?

While contemplating possible answers to this question, we may examine three further observations. First, the serpent iconography in ancient Palestine is markedly inferior to that found in some contiguous cultures. For example, the most elegant snake boxes are found only in Ugarit. Nowhere in Palestine is there a sophisticated work of ophidian art to compare to the magnificent serpent vase unearthed at Susa in Persia.

353

Likewise, nothing found in Palestine begins to compare with the artistry found so frequently in Egypt. The treasures in Tutankhamen’s tomb—many with ophidian iconography

354

—are only examples and not exceptions to the sophisticated serpent iconography so replete in ancient Egypt. Nowhere in ancient Palestine is there anything to compare with Egypt’s Sphinx, Nineveh’s winged bull, the serpent designs on Boeotian ceramics,

355

or the Phoenicians’ glass artwork.

356

Second, even including the numerous ophidian objects found at Beth Shan, no site in ancient Palestine can be said to rival the vast amount of serpent objects and ophidian symbolism found elsewhere. For example, no one site from Dan to Beer-sheba has produced anything like the vast amount of ophidian iconography recovered from the “Mound of Serpents.” This site, which dates from that area’s Iron Age (circa 1200

BCE

to circa 250

BCE

), is in the Arabian Peninsula in Oman and in the small tell near the Al-Qusais graves.

357

Likewise, while a dog cemetery was found at Ashkelon, no serpent burials have been discovered in ancient Palestine like the forty “snake bowls” with skeletons of serpents often curled around a precious gem like a pearl. These were found beneath the floor of the Palace of Uperi at Qal’at Bahrain, which dates from the seventh century

BCE

.

358

Finally, no ancient place in Palestine has produced the amount and variety of serpent iconography so typical of sites in Italy, Greece, and Egypt.

359

Third, the ophidian iconography found in ancient Palestine is basic or realistic; that is, the object is clearly a serpent or an idealized serpent. There are no mixed figures, such as we will see in the Greek and Roman world, like chimera, that is, a lion with a ram protruding from his back and with a serpent as a tail, the Giants with anguipedes, or Medusa with serpents protruding from her hair. Furthermore, nothing found in ancient Palestine is similar to the “snake-dragon” and “lion-dragon” so common in the iconography of ancient Mesopotamia.

360

CONCLUSION

Snakes are not drawn to exercise artists’ fingers. The iconography represents a need. Whenever the serpent could be physically present among us and where humans have left traces we find serpent iconography. To make a form of a serpent or to draw one, no matter how primitive, is to express the “I” and the “We.” Such drawings of serpents help us connect with each other and with nature, including life and death. The human needs symbols and needs to make them. We pour ourselves into symbols and in so doing express our fears and hopes. In serpent iconography, humans, since 40,000

BCE

, have found a way of finding the self.

In its very nature of being able to represent—at once and immediately—two opposites, the serpent signifies the archetypal, primordial, and phenomenological mode of symbology. It articulates for us our presence in this world. We approach truth; that is, the insight sought through the tension symbolized by two opposites: life-death, truth-falsehood, and good-evil. Sometimes truth comes in pairs: father-son, heaven-earth, morning-night, man-woman. From myths that even antedate 40,000

BCE

we observe the primordial need of all humans: to express in storied forms the attempt to obtain meaning within a chaotically uncategorical meaningless cascade of phenomena. Human existence and meaning tend to need symbolism.

There should be no doubt now that the vast amount of ophidian jewelry from Greek and Roman times heralds the serpent as a symbol of numerous positive meanings, including beauty, protection, and comfort.

361

For a millennium, and more, the serpent had been associated in Mediterranean cultures with the feminine and goddesses. By the time of the Fourth Evangelist, the serpent had lost most of its evil symbolic meanings. As R. S. Bianchi states, the serpent “was primarily linked with goddesses who were considered protectors of women. It became fashionable to wear golden finger rings and bracelets in the shape of snakes, which would wrap their protective curls around the wearer’s finger or wrist.”

362

We have reviewed succinctly the evidence of such impressive ophidian jewelry from the West and the East. Some of the most stunning examples are the golden bracelets from Pompeii, which we know were being worn during the life of the Fourth Evangelist who was probably not born after 79

CE

, when Pompeii was covered with ash from Vesuvius.

| 4 | | The Perception That the Serpent Is a Positive Symbol in Greek and Roman Literature |

If we were to proceed chronologically, we would now begin a study of serpent imagery in the Old Testament (Hebrew Bible). It is best, for three reasons, to reserve the examination of biblical passages until the Greek and Roman data have been assessed. First, biblical studies demand the same methodology as all ancient literature, but the issues become very complex and often demand reexamining set presuppositions and cultural animus for or against these texts. Second, the Greek data canvasses many centuries; it does not simply begin after the last book in the Old Testament, Daniel, was composed and compiled about 164

BCE

. Hence, a chronological approach would be prima facie impossible. Third, it would be absurd to think that we should attend to the date of an example of serpent iconography as if the symbology appeared only then. The date of an artifact is not a reliable date for iconography. A gold, silver, or bronze serpent can be found in a Roman stratification of a site, but the object may antedate the stratum by many years. Valuable and imperishable objects were used and passed down, and ancient graves were robbed by Romans, as they are today by Bedouin.

GREEK AND ROMAN OPHIDIAN SYMBOLISM AND IRANIAN MYTHOLOGY

In contrast to other ancient cultures, with the exception of the Egyptian religion, the Greeks, followed closely by the Romans, employed serpent symbolism the most. Both the Greeks and the Romans were deeply influenced by Egyptian ophidian symbolism. The unique development of ophidian symbolism within Greek and Roman art and culture becomes clear when one contrasts Greek and Roman myths with Persian myths.

The evil god Angra Mainyu (Ahriman) does sometimes change into a lizard or a serpent. In a second-century

CE

stone carving he appears with two raised serpents near his left shoulder, and perhaps two serpents protruding from each shoulder.

1

The warrior and physician called Thraetaona is “the most victorious of all victorious men next to Zarathustra”

(Avesta, Yasht

19.36–37).

2

He cures the evil caused by the serpent, and he battles dragons. According to the early myths in the Shahnameh

(Book of Kings

[c. 1010

CE])

, evils and death are caused by black demons called

“divs,”

which are not personifications of Ahriman, Satan, but represent enemy kings.

3

Shahnameh art of the eighteenth century

CE

shows Rustam and his horse Rakhsh defeating a monstrous dragon. In addition to the pervasive negative meaning of a serpent and dragon, one finds positive meanings for the serpent in Persia. For example, in early Roman times Mithra is depicted in a Tauroctony virtually everywhere from upper Germany to Persia.

4

That is, Mithra (in Latin Arimanius) is shown slaying a bull: he is accompanied by a serpent, a scorpion, and a dog. Aeon (Zrvan Akarana), a lion-faced god in Mithraism, appears with serpent coils surrounding his body; these represent the repetitious nature of time.

5

Yet the dominant image in such widespread depictions of the Tauroctony is not the serpent; it is Mithra followed by the bull. Sometimes in Rome and the West, Mithra appears with a lion’s head and serpent feet (anguipedes).

6

An ambiguous figure in Mithraism is a lion-headed statue with a body that is entwined by a snake. The image may denote Aion, Chronos, or Zurvan, and while some scholars (like S. Insler) think the figure should be associated with the evil god Ahriman, most scholars interpret it to denote some benevolent deity.

7

Thus, serpent iconography is found in Iranian religion, literature, and art. Most of it dates from Christian times, but there is some from preChristian eras. Yet, in contrast to Egyptian and Greek and Roman culture, serpent and dragon images do not abound in Persian culture. Thus, we should distinguish between searching for evidence and the actual evidence.

Greek and Roman Serpent Symbolism: An Overview

In contrast to Persian culture, images of serpents permeate Greek and Roman literature, art, and culture. To grasp the significance of the in-depth exploration that will soon commence, it is wise to get an overview of the area for exploration.

Ophidian or anguine iconography appears on the painted walls of homes in Pompeii, on pithoi (large storage jars), on ornately decorated jars (like the Athenian red-figured hydria (water jars), on coins, and through words in epics, poems, and official documents.

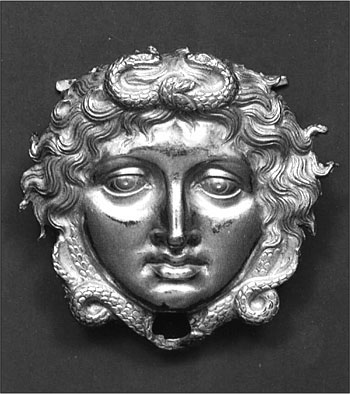

Figure 47

. Gorgon with Two Elegant Serpents Highlighted on Head. Royal Tomb at Vergina. Circa 350–336 BCE. Courtesy of the Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki.

It is impressive to note how ophidian or anguine symbolism permeates Greek and Roman legends and myths, shaping Hellenistic culture. Demeter and her daughter, Persephone, are often depicted sending Triptolemus to humans with the gift of wheat. He is often shown seated on a chariot drawn by raised serpents (see the final section on serpents and chariots).

8

Well known on buildings and painted vases, beginning at least in the eighth century

BCE

, are depictions of Medusa. She and the other Gorgons are shown as women with serpents rising from their hair. Serpents are the ones who reveal to Melampus the languages of animals; he thus becomes the first human with prophetic powers. The serpents had licked his ears when he was sleeping. Scylla had six snaky heads. Basilisk is the king of serpents. Asclepius almost always appears with a staff around which a serpent is coiled, and Hermes is associated with the caduceus (two raised serpents facing each other).

Ovid describes Phaeton’s ill-fated ride into the heavens on a chariot. The venture resulted in cosmic disasters; in particular, the Serpent, which had been coiled harmlessly around the North Pole, rises with rage. In order to avoid the advances of Peleus, Thetis changes into fire, monsters, and serpents. When Priam’s wife was pregnant with Paris, she dreamed of giving birth to a torch from which streamed hissing serpents. When Laocoon, Poseidon’s priest during the Trojan War, warned about the wooden horse the Greeks had left, he and his two sons were strangled by two massive serpents that had been called out of the sea, presumably by the warlike Athena (more will be said about Laocoon).

In the legend of the Golden Fleece, perhaps older than the

Iliad

and the

Odyssey

,

9

Aeetes hangs the fleece in a grove that was guarded by a serpent. Before Jason can obtain the Golden Fleece, he must defeat armed warriors who originate from the teeth of the dreadful serpent, who had guarded Ares’ pool but had been defeated by Kadmos. The maenads are women who became ecstatic during the worship of Dionysus; they often are depicted as those who charmed serpents.